Research Journal I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

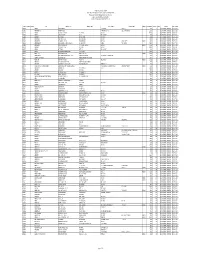

Accused Persons Arrested in Palakkad District from 18.10.2015 to 24.10.2015

Accused Persons arrested in Palakkad district from 18.10.2015 to 24.10.2015 Name of the Name of Name of the Place at Date & Court at Sl. Name of the Age & Cr. No & Sec Police Arresting father of Address of Accused which Time of which No. Accused Sex of Law Station Officer, Rank Accused Arrested Arrest accused & Designation produced 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Near Village Office, T.K. Muhammed Noorani 1531/15 U/s Town South 1 Riyas 32 Puthunagaram, 18.10.15 Radhakrishnan, Bail by Police Musthafa Gramam 151 CRPC PS Palakkad Addl SI of Police 35/I, Iind Street, Rose T.K. Muhammed Noorani 1531/15 U/s Town South 2 Lyakhath Ali 42 Garden, South 18.10.15 Radhakrishnan, Bail by Police Rafi Gramam 151 CRPC PS Ukkadam, Coimbatore Addl SI of Police T.K. Karimbukada, Noorani 1531/15 U/s Town South 3 Riyasudheen Sirajudheen 29 18.10.15 Radhakrishnan, Bail by Police Coimbatore Gramam 151 CRPC PS Addl SI of Police T.K. Basheer Pothanoor, Noorani 1531/15 U/s Town South 4 Safi Ahammed 32 18.10.15 Radhakrishnan, Bail by Police Ahammed Coimbatore Gramam 151 CRPC PS Addl SI of Police Al Ameen Colony, T.K. Muhammed Noorani 1531/15 U/s Town South 5 Shahul Hameed 27 South Ukkadam, 18.10.15 Radhakrishnan, Bail by Police Yousaf Gramam 151 CRPC PS Coimbatore Addl SI of Police Husaya Plastic, T.K. Noormuhamme Noorani 1531/15 U/s Town South 6 Hidayathulla 36 Chikanampara, 18.10.15 Radhakrishnan, Bail by Police d Gramam 151 CRPC PS Kollengode Addl SI of Police Unnanchathan T.K. -

9 State Forest Management and Biodiversity: a Case of Kerala, India

9 State Forest Management and Biodiversity: A Case of Kerala, India Ellyn K. DAMAYANTI & MASUDA Misa 1. Introduction Republic of India is the seventh largest country in the world, covering an area of 3,287,263 km2.has large and diverse forest resources in 633,397 km2 of forest covers or 19.27% of land areas (ICFRE, 2003; FAO, 2003). Forest types in India vary from topical rainforest in northeastern India, to desert and thorn forests in Gujarat and Rajasthan; mangrove forests in West Bengal, Orissa and other coastal areas; and dry alpine forests in the western Himalaya. The most common forest types are tropical moist deciduous forest, tropical dry deciduous forests, and wet tropical evergreen forests. India has a large network of protected areas, including 89 national parks and around 497 wildlife sanctuaries (MoEF, 2005). India has long history in forest management. The first formal government approach to forest management can be traced to the enactment of the National Forest Policy of 1894, revised in 1952 and once again revised in 1988, which envisaged community involvement in the protection and regeneration of forest (MoEF, 2003). Even having large and diverse forest resources, India’s national goal is to have a minimum of one-third of the total land area of the country under forest or tree cover (MoEF, 1988). In management of state forests, the National Forest Policy, 1988 emphasizes schemes and projects, which interfere with forests that clothe slopes; catchments of rivers, lakes, and reservoirs, geologically unstable terrain and such other ecologically sensitive areas, should be severely restricted. -

Payment Locations - Muthoot

Payment Locations - Muthoot District Region Br.Code Branch Name Branch Address Branch Town Name Postel Code Branch Contact Number Royale Arcade Building, Kochalummoodu, ALLEPPEY KOZHENCHERY 4365 Kochalummoodu Mavelikkara 690570 +91-479-2358277 Kallimel P.O, Mavelikkara, Alappuzha District S. Devi building, kizhakkenada, puliyoor p.o, ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 4180 PULIYOOR chenganur, alappuzha dist, pin – 689510, CHENGANUR 689510 0479-2464433 kerala Kizhakkethalekal Building, Opp.Malankkara CHENGANNUR - ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 3777 Catholic Church, Mc Road,Chengannur, CHENGANNUR - HOSPITAL ROAD 689121 0479-2457077 HOSPITAL ROAD Alleppey Dist, Pin Code - 689121 Muthoot Finance Ltd, Akeril Puthenparambil ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 2672 MELPADAM MELPADAM 689627 479-2318545 Building ;Melpadam;Pincode- 689627 Kochumadam Building,Near Ksrtc Bus Stand, ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 2219 MAVELIKARA KSRTC MAVELIKARA KSRTC 689101 0469-2342656 Mavelikara-6890101 Thattarethu Buldg,Karakkad P.O,Chengannur, ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 1837 KARAKKAD KARAKKAD 689504 0479-2422687 Pin-689504 Kalluvilayil Bulg, Ennakkad P.O Alleppy,Pin- ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 1481 ENNAKKAD ENNAKKAD 689624 0479-2466886 689624 Himagiri Complex,Kallumala,Thekke Junction, ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 1228 KALLUMALA KALLUMALA 690101 0479-2344449 Mavelikkara-690101 CHERUKOLE Anugraha Complex, Near Subhananda ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 846 CHERUKOLE MAVELIKARA 690104 04793295897 MAVELIKARA Ashramam, Cherukole,Mavelikara, 690104 Oondamparampil O V Chacko Memorial ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 668 THIRUVANVANDOOR THIRUVANVANDOOR 689109 0479-2429349 -

Junior Executive (Airside Operations/Finance/Office Support/Engineering /Terminal Operations/HR/ IT & Electronics) I

KANNUR INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT LTD. (KIAL) Selection of Junior Executive (Airside Operations/Finance/Office Support/Engineering /Terminal Operations/HR/ IT & Electronics) I. Qualification required as per notification : 1. Educational Qualification : First Class Graduate in any discipline or First Class Engineering Graduate in Electrical/Civil/Electronics & Communication/Computer Science/Mechanical/Instrumental/Auto mobile/Information Technology. MBA will be a desirable additional qualification. A valid LMV Licence issued by Indian Authority with three years experience is must for Junior Executive (Airside Operations). A valid LMV licence is desirable for other posts. 2. Age : 35 years as on 31/03/2017. II. List of Rejected applications not meeting the above mentioned eligibility criteria. This list is prepared based on the details provided by the candidates in the online application form. If the rejected candidate has any valid proof to be included in the provisionally accepted list of candidates, they need to forward a request along with a copy of proof of their claims to [email protected] on or before 11.09.2017 . Request without valid proof of claims will not be considered. Sl No. Ref. No. Name of Candidate Reason for Rejection 1 KA-17226 VSHNU SASIDHARAN No Prescribed Qualification 2 KA-17229 Saneesh. A No Prescribed Qualification 3 KA-17231 John Thomas Moolayil No Experience 4 KA-17240 Aravind Raveendranadh No Prescribed Qualification 5 KA-17242 Johil R No Prescribed Qualification 6 KA-17244 SNEHA R No Experience 7 KA-17254 -

List of Teachers Posted from the Following Schools to Various Examination Centers As Assistant Superintendents for Higher Secondary Exam March 2015

LIST OF TEACHERS POSTED FROM THE FOLLOWING SCHOOLS TO VARIOUS EXAMINATION CENTERS AS ASSISTANT SUPERINTENDENTS FOR HIGHER SECONDARY EXAM MARCH 2015 08001 - GOVT SMT HSS,CHELAKKARA,THRISSUR 1 DILEEP KUMAR P V 08015-GOVT HSS,CHERUTHURUTHY,THRISSUR 04884231495, 9495222963 2 SWAPNA P 08015-GOVT HSS,CHERUTHURUTHY,THRISSUR , 9846374117 3 SHAHINA.K 08035-GOVT. RSR VHSS, VELUR, THRISSUR 04885241085, 9447751409 4 SEENA M 08041-GOVT HSS,PAZHAYANNOOR,THRISSUR 04884254389, 9447674312 5 SEENA P.R 08046-AKM HSS,POOCHATTY,THRISSUR 04872356188, 9947088692 6 BINDHU C 08062-ST ANTONY S HSS,PUDUKAD,THRISSUR 04842331819, 9961991555 7 SINDHU K 08137-GOVT. MODEL HSS FOR GIRLS, THRISSUR TOWN, , 9037873800 THRISSUR 8 SREEDEVI.S 08015-GOVT HSS,CHERUTHURUTHY,THRISSUR , 9020409594 9 RADHIKA.R 08015-GOVT HSS,CHERUTHURUTHY,THRISSUR 04742552608, 9847122431 10 VINOD P 08015-GOVT HSS,CHERUTHURUTHY,THRISSUR , 9446146634 11 LATHIKADEVI L A 08015-GOVT HSS,CHERUTHURUTHY,THRISSUR 04742482838, 9048923857 12 REJEESH KUMAR.V 08015-GOVT HSS,CHERUTHURUTHY,THRISSUR 04762831245, 9447986101 08002 - GOVT HSS,CHERPU,THRISSUR 1 PREETHY M K 08003-GOVT MODEL GHSS, IRINJALAKKUDA, THRISSUR 04802820505, 9496288495 2 RADHIKA C S 08003-GOVT MODEL GHSS, IRINJALAKKUDA, THRISSUR , 9495853650 3 THRESSIA A.O 08005-GOVT HSS,KODAKARA,THRISSUR 04802726280, 9048784499 4 SMITHA M.K 08046-AKM HSS,POOCHATTY,THRISSUR 04872317979, 8547619054 5 RADHA M.R 08050-ST ANTONY S HSS,AMMADAM,THRISSUR 04872342425, 9497180518 6 JANITHA K 08050-ST ANTONY S HSS,AMMADAM,THRISSUR 04872448686, 9744670871 1 7 SREELEKHA.E.S 08050-ST ANTONY S HSS,AMMADAM,THRISSUR 04872343515, 9446541276 8 APINDAS T T 08095-ST. PAULS CONVENT EHSS KURIACHIRA, THRISSUR, 04872342644, 9446627146 680006 9 M.JAMILA BEEVI 08107-SN GHSS, KANIMANGALAM, THRISSUR, 680027 , 9388553667 10 MANJULA V R 08118-TECHNICAL HSS, VARADIAM, THRISSUR, 680547 04872216227, 9446417919 11 BETSY C V 08138-GOVT. -

A CONCISE REPORT on BIODIVERSITY LOSS DUE to 2018 FLOOD in KERALA (Impact Assessment Conducted by Kerala State Biodiversity Board)

1 A CONCISE REPORT ON BIODIVERSITY LOSS DUE TO 2018 FLOOD IN KERALA (Impact assessment conducted by Kerala State Biodiversity Board) Editors Dr. S.C. Joshi IFS (Rtd.), Dr. V. Balakrishnan, Dr. N. Preetha Editorial Board Dr. K. Satheeshkumar Sri. K.V. Govindan Dr. K.T. Chandramohanan Dr. T.S. Swapna Sri. A.K. Dharni IFS © Kerala State Biodiversity Board 2020 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, tramsmitted in any form or by any means graphics, electronic, mechanical or otherwise, without the prior writted permission of the publisher. Published By Member Secretary Kerala State Biodiversity Board ISBN: 978-81-934231-3-4 Design and Layout Dr. Baijulal B A CONCISE REPORT ON BIODIVERSITY LOSS DUE TO 2018 FLOOD IN KERALA (Impact assessment conducted by Kerala State Biodiversity Board) EdItorS Dr. S.C. Joshi IFS (Rtd.) Dr. V. Balakrishnan Dr. N. Preetha Kerala State Biodiversity Board No.30 (3)/Press/CMO/2020. 06th January, 2020. MESSAGE The Kerala State Biodiversity Board in association with the Biodiversity Management Committees - which exist in all Panchayats, Municipalities and Corporations in the State - had conducted a rapid Impact Assessment of floods and landslides on the State’s biodiversity, following the natural disaster of 2018. This assessment has laid the foundation for a recovery and ecosystem based rejuvenation process at the local level. Subsequently, as a follow up, Universities and R&D institutions have conducted 28 studies on areas requiring attention, with an emphasis on riverine rejuvenation. I am happy to note that a compilation of the key outcomes are being published. -

Mallapuram-District

Aum Sri Sai Ram MALAPPURAM DISTRICT ANNUAL REPORT FOR THE PERIOD FROM 1 ST APRIL 2018 TO 31 ST MARCH 2019 Contents FOREWORD FROM THE DISTRICT PRESIDENT ............................. ERROR! BOOKMARK NOT DEFINED. SRI SATHYA SAI SEVA ORGANISATIONS – AN INTRODUCTION ....................................................... 2 WINGS OF THE ORGANISATIONS ................................................................................................................. 3 ADMINISTRATION OF THE ORGANISATION ..................................................................................................... 3 THE 9 POINT CODE OF CONDUCT AND 10 PRINCIPLES ..................................................................................... 4 SRI SATHYA SAI SEVA ORGANISATIONS, MALAPPURAM ............................................................... 5 BRIEF HISTORY ........................................................................................................................................ 5 DIVINE VISIT ........................................................................................................................................... 7 OVERVIEW ............................................................................................................................................. 8 SAI CENTRES ........................................................................................................................................... 9 ACTIVITIES ........................................................................................................................................... -

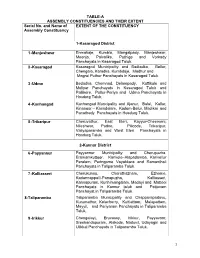

List of Lacs with Local Body Segments (PDF

TABLE-A ASSEMBLY CONSTITUENCIES AND THEIR EXTENT Serial No. and Name of EXTENT OF THE CONSTITUENCY Assembly Constituency 1-Kasaragod District 1 -Manjeshwar Enmakaje, Kumbla, Mangalpady, Manjeshwar, Meenja, Paivalike, Puthige and Vorkady Panchayats in Kasaragod Taluk. 2 -Kasaragod Kasaragod Municipality and Badiadka, Bellur, Chengala, Karadka, Kumbdaje, Madhur and Mogral Puthur Panchayats in Kasaragod Taluk. 3 -Udma Bedadka, Chemnad, Delampady, Kuttikole and Muliyar Panchayats in Kasaragod Taluk and Pallikere, Pullur-Periya and Udma Panchayats in Hosdurg Taluk. 4 -Kanhangad Kanhangad Muncipality and Ajanur, Balal, Kallar, Kinanoor – Karindalam, Kodom-Belur, Madikai and Panathady Panchayats in Hosdurg Taluk. 5 -Trikaripur Cheruvathur, East Eleri, Kayyur-Cheemeni, Nileshwar, Padne, Pilicode, Trikaripur, Valiyaparamba and West Eleri Panchayats in Hosdurg Taluk. 2-Kannur District 6 -Payyannur Payyannur Municipality and Cherupuzha, Eramamkuttoor, Kankole–Alapadamba, Karivellur Peralam, Peringome Vayakkara and Ramanthali Panchayats in Taliparamba Taluk. 7 -Kalliasseri Cherukunnu, Cheruthazham, Ezhome, Kadannappalli-Panapuzha, Kalliasseri, Kannapuram, Kunhimangalam, Madayi and Mattool Panchayats in Kannur taluk and Pattuvam Panchayat in Taliparamba Taluk. 8-Taliparamba Taliparamba Municipality and Chapparapadavu, Kurumathur, Kolacherry, Kuttiattoor, Malapattam, Mayyil, and Pariyaram Panchayats in Taliparamba Taluk. 9 -Irikkur Chengalayi, Eruvassy, Irikkur, Payyavoor, Sreekandapuram, Alakode, Naduvil, Udayagiri and Ulikkal Panchayats in Taliparamba -

Accused Persons Arrested in Thrissur Rural District from 23.07.2017 to 29.07.2017

Accused Persons arrested in Thrissur Rural district from 23.07.2017 to 29.07.2017 Name of Name of the Name of the Place at Date & Arresting Court at Sl. Name of the Age & Cr. No & Sec Police father of Address of Accused which Time of Officer, which No. Accused Sex of Law Station Accused Arrested Arrest Rank & accused Designation produced 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 MULLACKKAL 23.07.201 CR.1519/17 U.K JFCM 31/17 HOUSE, KUNNAMKUL KUNNAMKU 1 DHANEESH JAMES 7 AT 12.15 U/S 279 337 SHAJAHAN KUNNAMKU MALE KOONAMOOCHI, AM LAM HRS 338 IPC SI OF POLICE LAM CHOONDAL KUTTIKARIPOTTIL CR.1536/17 23.07.201 U.K.SHAJAHA JFCM 21/17 HOUSE, KUNNAMKUL U/S 342 323 KUNNAMKU 2 YAHIYA MUSTAFA 7 AT 22.30 N SI KUNNAMKU MALE PERUMPILAVU, AM 427 364 (A ) LAM HRS OF POLICE LAM ANAKKALLU 34 IPC CR.1536/17 CHERATH HOUSE, 23.07.201 U.K.SHAJAHA JFCM KUNJUMUH 26/17 KUNNAMKUL U/S 342 323 KUNNAMKU 3 JISHAD OTTAPPILAVU, 7 AT 22.30 N SI KUNNAMKU AMMED MALE AM 427 364 (A ) LAM KADAVALLUR HRS OF POLICE LAM 34 IPC CR.1536/17 23.07.201 U.K JFCM 29/17 PANIKKAVEETTIL KUNNAMKUL U/S 342 323 KUNNAMKU 4 SALEEM MOOSA 7 AT 22.30 SHAJAHAN KUNNAMKU MALE HOUSE, CHALISSERY AM 427 364 (A ) LAM HRS SI OF POLICE LAM 34 IPC PAPPANKATTIL CR.1536/17 23.07.201 U.K JFCM ABDUL MUHAMME 27/17 HOUSE, KUNNAMKUL U/S 342 323 KUNNAMKU 5 7 AT 22.30 SHAJAHAN KUNNAMKU RAHMAN DKUTTY MALE OTTAPPILAVU, AM 427 364 (A ) LAM HRS SI OF POLICE LAM KADAVALLUR 34 IPC VARIYATHVALAPPIL 23.07.201 CR.470/17 MANOJ K JFCM 28/17 HOUSE KANJOOR PANNITHADA ERUMAPETT 6 SHEHEER HUSSAN 7 AT 22.05 U/S 15 (C ) OF GOPI WADAKKAN MALE DESAM -

Filippo Osella, University of Sussex, UK

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by SOAS Research Online Chapter 9 “I am Gulf”: The production of cosmopolitanism among the Koyas of Kozhikode, Kerala Filippo Osella, University of Sussex & Caroline Osella, SOAS, University of London Introduction: Kozhikode and the Gulf A few weeks after our arrival in Kozhikode (known as Calicut during colonial times) we were introduced to Abdulhussein (Abdulbhai), an export agent who runs a family business together with his three younger brothers. He sat behind a desk in his sparsely furnished office on Beach Road. Abdulbhai is reading a Gujarati newspaper, while one of his younger brothers is talking on the phone in Hindi to a client from Bombay. The office is quiet and so is business: our conversation is only interrupted by the occasional friend who peeps into the office to greet Abdulbhai. He begins: Business is dead, all the godowns (warehouses) along the beach are closed; all the other exporters have closed down. But at my father’s time it was all different. During the trade season, there would be hundreds of boats anchored offshore, with barges full of goods going to and fro. There were boats from Bombay, from Gujarat, from Burma and Ceylon, but most of them belonged to Arabs. Down the road there were the British warehouses, and on the other end there is the Beach Hotel, only Britishers stayed there. The beach front was busy with carts and lorries and there were hundreds of Arab sailors walking up and down. The Arab boats arrived as soon as the monsoon was over, in October, and the last left the following May, before the rain started. -

CSBL Unpaid Dividend, Refund Consolidated As on 22.09.2015.Xlsx

The Catholic Syrian Bank Limited Regd. Office, "CSB Bhavan", St. Mary's College Road, Thrissur 680020 Phone: 0487 -2333020, 6451640, eMail: [email protected] List of Unpaid Dividend as on 22.09.2015 (Dividend for the periods 2007-08 to 2013-14) FOLIO / DEMAT ID INITLS NAME ADDRESS LINE 1 ADDRESS LINE 2 ADDRESS LINE 3 ADDRESS LINE 4 PINCOD DIV.AMOUNT DWNO MICR PERIOD IEPF. TR. DATE A00350 ANTONY PALLANS HOUSE KURIACHARA TRICHUR, 30.00 0 2007-08 UNPAID DIVIDEND 25-OCT-2015 A00385 ANNAMMA P X AKKARA HOUSE PANAMKUTTICHIRA OLLUR, TRICHUR DIST 150.00 5 2007-08 UNPAID DIVIDEND 25-OCT-2015 A00398 ANTONY KUTTENCHERY HOUSE HIGH ROAD TRICHUR 1020.00 0 2007-08 UNPAID DIVIDEND 25-OCT-2015 A00406 ANTONY KALLIATH HOUSE OLLUR TRICHUR DIST 27.00 9 2007-08 UNPAID DIVIDEND 25-OCT-2015 A00409 ANTHONY PLOT NO 143 NEHRU NAGAR TRICHUR-6 120.00 0 2007-08 UNPAID DIVIDEND 25-OCT-2015 A00643 ANTHAPPAN PADIKKALA HOUSE EAST FORT GATE TRICHUR 540.00 12 2007-08 UNPAID DIVIDEND 25-OCT-2015 A00647 ANTHONY O K OLAKKENGAL HOUSE LOURDEPURAM TRICHUR - KERALA STATE. 680005 180.00 13 2007-08 UNPAID DIVIDEND 25-OCT-2015 A00668 ANTHONISWAMI C/O INASIMUTHU MUDALIAR SONS 55 NEW STREET KARUR TAMILNADU 2100.00 14 2007-08 UNPAID DIVIDEND 25-OCT-2015 A00822 ANNA JACOB C/O J S MANAVALAN 5 V R NAGAR ADAYAR MADRAS - 600020 210.00 18 2007-08 UNPAID DIVIDEND 25-OCT-2015 A01072 ANTHONY VI/62 PALACE VIEW EAST FORT TRICHUR 4200.00 0 2007-08 UNPAID DIVIDEND 25-OCT-2015 A01077 ANTONY KOTTEKAD KUTTUR TRICHUR DIST 30.00 0 2007-08 UNPAID DIVIDEND 25-OCT-2015 A01103 ANTONY ELUVATHINGAL CHERUVATHERI -

Ahtl-European STRUGGLE by the MAPPILAS of MALABAR 1498-1921 AD

AHTl-EUROPEAn STRUGGLE BY THE MAPPILAS OF MALABAR 1498-1921 AD THESIS SUBMITTED FDR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE DF Sactnr of pitilnsopliQ IN HISTORY BY Supervisor Co-supervisor PROF. TARIQ AHMAD DR. KUNHALI V. Centre of Advanced Study Professor Department of History Department of History Aligarh Muslim University University of Calicut Al.garh (INDIA) Kerala (INDIA) T6479 VEVICATEV TO MY FAMILY CONTENTS SUPERVISORS' CERTIFICATE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT LIST OF MAPS LIST OF APPENDICES ABBREVIATIONS Page No. INTRODUCTION 1-9 CHAPTER I ADVENT OF ISLAM IN KERALA 10-37 CHAPTER II ARAB TRADE BEFORE THE COMING OF THE PORTUGUESE 38-59 CHAPTER III ARRIVAL OF THE PORTUGUESE AND ITS IMPACT ON THE SOCIETY 60-103 CHAPTER IV THE STRUGGLE OF THE MAPPILAS AGAINST THE BRITISH RULE IN 19™ CENTURY 104-177 CHAPTER V THE KHILAFAT MOVEMENT 178-222 CONCLUSION 223-228 GLOSSARY 229-231 MAPS 232-238 BIBLIOGRAPHY 239-265 APPENDICES 266-304 CENTRE OF ADVANCED STUDY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH - 202 002, INDIA CERTIFICATE This is to certify that the thesis "And - European Struggle by the Mappilas of Malabar 1498-1921 A.D." submitted for the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the Aligarh Muslim University, is a record of bonafide research carried out by Salahudheen O.P. under our supervision. No part of the thesis has been submitted for award of any degree before. Supervisor Co-Supervisor Prof. Tariq Ahmad Dr. Kunhali.V. Centre of Advanced Study Prof. Department of History Department of History University of Calicut A.M.U. Aligarh Kerala ACKNOWLEDGEMENT My earnest gratitude is due to many scholars teachers and friends for assisting me in this work.