Feedback Inhibition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

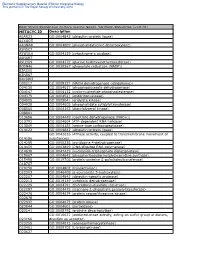

METACYC ID Description A0AR23 GO:0004842 (Ubiquitin-Protein Ligase

Electronic Supplementary Material (ESI) for Integrative Biology This journal is © The Royal Society of Chemistry 2012 Heat Stress Responsive Zostera marina Genes, Southern Population (α=0. -

Generate Metabolic Map Poster

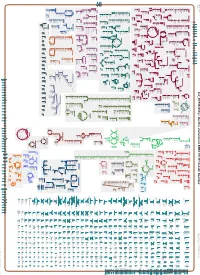

Authors: Pallavi Subhraveti Ron Caspi Peter Midford Peter D Karp An online version of this diagram is available at BioCyc.org. Biosynthetic pathways are positioned in the left of the cytoplasm, degradative pathways on the right, and reactions not assigned to any pathway are in the far right of the cytoplasm. Transporters and membrane proteins are shown on the membrane. Ingrid Keseler Periplasmic (where appropriate) and extracellular reactions and proteins may also be shown. Pathways are colored according to their cellular function. Gcf_001591825Cyc: Bacillus vietnamensis NBRC 101237 Cellular Overview Connections between pathways are omitted for legibility. Anamika Kothari sn-glycerol phosphate phosphate pro phosphate phosphate phosphate thiamine molybdate D-xylose D-ribose glutathione 3-phosphate D-mannitol L-cystine L-djenkolate lanthionine α,β-trehalose phosphate phosphate [+ 3 more] α,α-trehalose predicted predicted ABC ABC FliY ThiT XylF RbsB RS10935 UgpC TreP PutP RS10200 PstB PstB RS10385 RS03335 RS20030 RS19075 transporter transporter of molybdate of phosphate α,β-trehalose 6-phosphate L-cystine D-xylose D-ribose sn-glycerol D-mannitol phosphate phosphate thiamine glutathione α α phosphate phosphate phosphate phosphate L-djenkolate 3-phosphate , -trehalose 6-phosphate pro 1-phosphate lanthionine molybdate phosphate [+ 3 more] Metabolic Regulator Amino Acid Degradation Amine and Polyamine Biosynthesis Macromolecule Modification tRNA-uridine 2-thiolation Degradation ATP biosynthesis a mature peptidoglycan a nascent β an N-terminal- -

Saccharomyces Cerevisiae Aspartate Kinase Mechanism and Inhibition

In compliance with the Canadian Privacy Legislation some supporting forms may have been removed from this dissertation. While these forms may be included in the document page count, their removal does not represent any loss of content from the dissertation. Ph.D. Thesis - D. Bareich McMaster University - Department of Biochemistry FUNGAL ASPARTATE KINASE MECHANISM AND INHIBITION By DAVID C. BAREICH, B.Sc. A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy McMaster University © Copyright by David C. Bareich, June 2003 1 Ph.D. Thesis - D. Bareich McMaster University - Department of Biochemistry FUNGAL ASPARTATE KINASE MECHANISM AND INHIBITION Ph.D. Thesis - D. Bareich McMaster University - Department of Biochemistry DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (2003) McMaster University (Biochemistry) Hamilton, Ontario TITLE: Saccharomyces cerevisiae aspartate kinase mechanism and inhibition AUTHOR: David Christopher Bareich B.Sc. (University of Waterloo) SUPERVISOR: Professor Gerard D. Wright NUMBER OF PAGES: xix, 181 11 Ph.D. Thesis - D. Bareich McMaster University - Department of Biochemistry ABSTRACT Aspartate kinase (AK) from Saccharomyces cerevisiae (AKsc) catalyzes the first step in the aspartate pathway responsible for biosynthesis of L-threonine, L-isoleucine, and L-methionine in fungi. Little was known about amino acids important for AKsc substrate binding and catalysis. Hypotheses about important amino acids were tested using site directed mutagenesis to substitute these amino acids with others having different properties. Steady state kinetic parameters and pH titrations of the variant enzymes showed AKsc-K18 and H292 to be important for binding and catalysis. Little was known about how the S. cerevisiae aspartate pathway kinases, AKsc and homoserine kinase (HSKsc), catalyze the transfer of the y-phosphate from adenosine triphosphate (ATP) to L-aspartate or L-homoserine, respectively. -

Identification of Six Novel Allosteric Effectors of Arabidopsis Thaliana Aspartate Kinase-Homoserine Dehydrogenase

Identification of six novel allosteric effectors of Arabidopsis thaliana Aspartate kinase-Homoserine dehydrogenase. Physiological context sets the specificity Gilles Curien, Stéphane Ravanel, Mylène Robert, Renaud Dumas To cite this version: Gilles Curien, Stéphane Ravanel, Mylène Robert, Renaud Dumas. Identification of six novel allosteric effectors of Arabidopsis thaliana Aspartate kinase-Homoserine dehydrogenase. Physiological context sets the specificity. Journal of Biological Chemistry, American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, 2005, 280 (50), pp.41178-41183. 10.1074/jbc.M509324200. hal-00016689 HAL Id: hal-00016689 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00016689 Submitted on 31 May 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. THE JOURNAL OF BIOLOGICAL CHEMISTRY VOL. 280, NO. 50, pp. 41178–41183, December 16, 2005 © 2005 by The American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Inc. Printed in the U.S.A. Identification of Six Novel Allosteric Effectors of Arabidopsis thaliana Aspartate Kinase-Homoserine Dehydrogenase -

E1 E2 E3 E4 E5 Pi

Biochemistry I Problem Set 9 - Key November 10, 2019 Due Tuesday, November 19 Estimated time: ~ 75 minutes 1. (10 pts, 15 min) The metabolic pathway for the synthesis of threonine is shown on Aspartate the right. Note that not all reactants/products are shown for each reaction. COOH i) The first step in this pathway is phosphorylation of a carboxylic acid. The H N CH phosphorylation of a carboxylic acid by inorganic phosphate is unfavorable, 2 CH with a Go of approximately +30 kJ/mol yet the reaction proceeds 2 spontaneously in the forward direction. How can the Gibbs energy, G, COOH become negative for this step in the pathway (2 pts). E1 Direct coupling using ATP as the phosphate donor. Energy is released by COOH transferring the phosphate from ATP to aspartate, i.e. the energy of ATP is H N CH Aspartyl 2 Phosphate higher than Aspartyl phosphate CH2 ii) Provide a name for the enzyme (E1) that catalyzes the first step of this reaction, C PO3 based on your answer to part i) (2 pts). O 14 O A phosphate group is added, most likely from ATP, so this is a kinase – E2 Pi Aspartate kinase. COOH iii) How would you describe the chemical changes that occur between aspartyl H2N CH Aspartate semialdehyde phosphate and aspartate semialdehyde (catalyzed by enzyme E2)? What CH cofactor/co-substrate is likely involved in this step? Sample incorrect answer: 2 C This step is catalyzed by a phosphatase because a phosphate is released from O 22 H the substrate). [Hint: a similar reaction occurs in glycolysis, but in reverse. -

O O2 Enzymes Available from Sigma Enzymes Available from Sigma

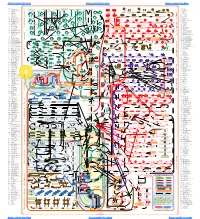

COO 2.7.1.15 Ribokinase OXIDOREDUCTASES CONH2 COO 2.7.1.16 Ribulokinase 1.1.1.1 Alcohol dehydrogenase BLOOD GROUP + O O + O O 1.1.1.3 Homoserine dehydrogenase HYALURONIC ACID DERMATAN ALGINATES O-ANTIGENS STARCH GLYCOGEN CH COO N COO 2.7.1.17 Xylulokinase P GLYCOPROTEINS SUBSTANCES 2 OH N + COO 1.1.1.8 Glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase Ribose -O - P - O - P - O- Adenosine(P) Ribose - O - P - O - P - O -Adenosine NICOTINATE 2.7.1.19 Phosphoribulokinase GANGLIOSIDES PEPTIDO- CH OH CH OH N 1 + COO 1.1.1.9 D-Xylulose reductase 2 2 NH .2.1 2.7.1.24 Dephospho-CoA kinase O CHITIN CHONDROITIN PECTIN INULIN CELLULOSE O O NH O O O O Ribose- P 2.4 N N RP 1.1.1.10 l-Xylulose reductase MUCINS GLYCAN 6.3.5.1 2.7.7.18 2.7.1.25 Adenylylsulfate kinase CH2OH HO Indoleacetate Indoxyl + 1.1.1.14 l-Iditol dehydrogenase L O O O Desamino-NAD Nicotinate- Quinolinate- A 2.7.1.28 Triokinase O O 1.1.1.132 HO (Auxin) NAD(P) 6.3.1.5 2.4.2.19 1.1.1.19 Glucuronate reductase CHOH - 2.4.1.68 CH3 OH OH OH nucleotide 2.7.1.30 Glycerol kinase Y - COO nucleotide 2.7.1.31 Glycerate kinase 1.1.1.21 Aldehyde reductase AcNH CHOH COO 6.3.2.7-10 2.4.1.69 O 1.2.3.7 2.4.2.19 R OPPT OH OH + 1.1.1.22 UDPglucose dehydrogenase 2.4.99.7 HO O OPPU HO 2.7.1.32 Choline kinase S CH2OH 6.3.2.13 OH OPPU CH HO CH2CH(NH3)COO HO CH CH NH HO CH2CH2NHCOCH3 CH O CH CH NHCOCH COO 1.1.1.23 Histidinol dehydrogenase OPC 2.4.1.17 3 2.4.1.29 CH CHO 2 2 2 3 2 2 3 O 2.7.1.33 Pantothenate kinase CH3CH NHAC OH OH OH LACTOSE 2 COO 1.1.1.25 Shikimate dehydrogenase A HO HO OPPG CH OH 2.7.1.34 Pantetheine kinase UDP- TDP-Rhamnose 2 NH NH NH NH N M 2.7.1.36 Mevalonate kinase 1.1.1.27 Lactate dehydrogenase HO COO- GDP- 2.4.1.21 O NH NH 4.1.1.28 2.3.1.5 2.1.1.4 1.1.1.29 Glycerate dehydrogenase C UDP-N-Ac-Muramate Iduronate OH 2.4.1.1 2.4.1.11 HO 5-Hydroxy- 5-Hydroxytryptamine N-Acetyl-serotonin N-Acetyl-5-O-methyl-serotonin Quinolinate 2.7.1.39 Homoserine kinase Mannuronate CH3 etc. -

Fortifying Horticultural Crops with Essential Amino Acids: a Review

Review Fortifying Horticultural Crops with Essential Amino Acids: A Review Guoping Wang 1, Mengyun Xu 1, Wenyi Wang 1,2,* and Gad Galili 2,* 1 College of Horticulture, South China Agricultural University, Guangzhou 510642, China; [email protected] (G.W.); [email protected] (M.X.) 2 Department of Plant Science, Weizmann Institute of Science, Rehovot 76100, Israel * Corresponding author: [email protected] (W.W.); [email protected] (G.G.); Tel.: +972-8-934-3511 (G.G.); Fax: +972-8-934-4181 (G.G.) Received: 17 May 2017; Accepted: 14 June 2017; Published: 19 June 2017 Abstract: To feed the world′s growing population, increasing the yield of crops is not the only important factor, improving crop quality is also important, and it presents a significant challenge. Among the important crops, horticultural crops (particularly fruits and vegetables) provide numerous health compounds, such as vitamins, antioxidants, and amino acids. Essential amino acids are those that cannot be produced by the organism and, therefore, must be obtained from diet, particularly from meat, eggs, and milk, as well as a variety of plants. Extensive efforts have been devoted to increasing the levels of essential amino acids in plants. Yet, these efforts have been met with very little success due to the limited genetic resources for plant breeding and because high essential amino acid content is generally accompanied by limited plant growth. With a deep understanding of the biosynthetic pathways of essential amino acids and their interactions with the regulatory networks in plants, it should be possible to use genetic engineering to improve the essential amino acid content of horticultural plants, rendering these plants more nutritionally favorable crops. -

Moted Lysine Incorporation Was Susceptible to Hy

54 BIOCHEMISTRY: KAZIRO ET AL. PROC. N. A. S. Applied Chemistry Symposium on Protein Structure, ed. A. Neuberger (New York: John Wiley and Sons, 1958). 7 Craig, L. C., T. P. King, and W. Konigsberg, Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci., 88, 571 (1960). 8 Craig, L. C., T. P. King, and A. Crestfield, Biopolymers, in press. 9 Craig, L. C., and W. Konigsberg, J. Phys. Chem., 65, 166 (1961). 10 Hill, R. J., W. Konigsberg, G. Guidotti, and L. C. Craig, J. Biol. Chem., 237, 1549 (1962). 11 Hasserodt, U., and J. Vinograd, these PROCEEDINGS, 45, 12 (1959). 12 Rossi-Fanelli, A., E. Antonini, and A. Caputo, J. Biol. Chem., 236, 391 (1961). Is Benesch, R. E., R. Benesch, and M. E. Williamson, these PROCEEDINGS, 48, 2071 (1962). 14 Antonini, E., J. Wyman, E. Bucci, C. Fronticelli, and A. Rossi-Fanelli, J. Mol. Biol., 4, 368 (1962). 16 Vinograd, J., and W. D. Hutchinson, Nature, 187, 216 (1960). 16Stracher, A., and L. C. Craig, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 81, 696 (1959). 17 Bromer, W. W., L. G. Sinn, A. Staub, and 0. K. Behrens, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 78, 3858 (1956). IsSquire, P. G., and C. H. Li, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 83, 3521 (1961). IDENTIFICATION OF PEPTIDES SYNTHESIZED BY THE CELL-FREE E. COLI SYSTEM WITH POLYNUCLEOTIDE MESSENGERS* BY YOSHITO KAZIRO, ALBERT GROSSMAN, AND SEVERO OCHOA DEPARTMENT OF BIOCHEMISTRY, NEW YORK UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF MEDICINE Communicated May 23, 1963 Characterization of the products formed by cell-free systems of protein synthesis as a result of the incorporation of amino acids into acid-insoluble products, pro- moted by synthetic polyribonucleotides, has lagged behind the use of these com- pounds in studies on the genetic code.1' 2 Nirenberg and Matthaei' partially characterized the product of phenylalanine incorporation by the Escherichia coli system, in the presence of poly U, as poly L-phenylalanine. -

Arabidopsis Transmembrane Receptor-Like Kinases (Rlks): a Bridge Between Extracellular Signal and Intracellular Regulatory Machinery

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Review Arabidopsis Transmembrane Receptor-Like Kinases (RLKs): A Bridge between Extracellular Signal and Intracellular Regulatory Machinery Jismon Jose y , Swathi Ghantasala y and Swarup Roy Choudhury * Department of Biology, Indian Institute of Science Education and Research (IISER) Tirupati, Tirupati, Andhra Pradesh 517507, India; [email protected] (J.J.); [email protected] (S.G.) * Correspondence: [email protected] These authors contributed equally to this work. y Received: 16 May 2020; Accepted: 1 June 2020; Published: 3 June 2020 Abstract: Receptors form the crux for any biochemical signaling. Receptor-like kinases (RLKs) are conserved protein kinases in eukaryotes that establish signaling circuits to transduce information from outer plant cell membrane to the nucleus of plant cells, eventually activating processes directing growth, development, stress responses, and disease resistance. Plant RLKs share considerable homology with the receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) of the animal system, differing at the site of phosphorylation. Typically, RLKs have a membrane-localization signal in the amino-terminal, followed by an extracellular ligand-binding domain, a solitary membrane-spanning domain, and a cytoplasmic kinase domain. The functional characterization of ligand-binding domains of the various RLKs has demonstrated their essential role in the perception of extracellular stimuli, while its cytosolic kinase domain is usually confined to the phosphorylation of their substrates to control downstream regulatory machinery. Identification of the several ligands of RLKs, as well as a few of its immediate substrates have predominantly contributed to a better understanding of the fundamental signaling mechanisms. In the model plant Arabidopsis, several studies have indicated that multiple RLKs are involved in modulating various types of physiological roles via diverse signaling routes. -

Genome-Scale Metabolic Network Analysis and Drug Targeting of Multi-Drug Resistant Pathogen Acinetobacter Baumannii AYE

Electronic Supplementary Material (ESI) for Molecular BioSystems. This journal is © The Royal Society of Chemistry 2017 Electronic Supplementary Information (ESI) for Molecular BioSystems Genome-scale metabolic network analysis and drug targeting of multi-drug resistant pathogen Acinetobacter baumannii AYE Hyun Uk Kim, Tae Yong Kim and Sang Yup Lee* E-mail: [email protected] Supplementary Table 1. Metabolic reactions of AbyMBEL891 with information on their genes and enzymes. Supplementary Table 2. Metabolites participating in reactions of AbyMBEL891. Supplementary Table 3. Biomass composition of Acinetobacter baumannii. Supplementary Table 4. List of 246 essential reactions predicted under minimal medium with succinate as a sole carbon source. Supplementary Table 5. List of 681 reactions considered for comparison of their essentiality in AbyMBEL891 with those from Acinetobacter baylyi ADP1. Supplementary Table 6. List of 162 essential reactions predicted under arbitrary complex medium. Supplementary Table 7. List of 211 essential metabolites predicted under arbitrary complex medium. AbyMBEL891.sbml Genome-scale metabolic model of Acinetobacter baumannii AYE, AbyMBEL891, is available as a separate file in the format of Systems Biology Markup Language (SBML) version 2. Supplementary Table 1. Metabolic reactions of AbyMBEL891 with information on their genes and enzymes. Highlighed (yellow) reactions indicate that they are not assigned with genes. No. Metabolism EC Number ORF Reaction Enzyme R001 Glycolysis/ Gluconeogenesis 5.1.3.3 ABAYE2829 -

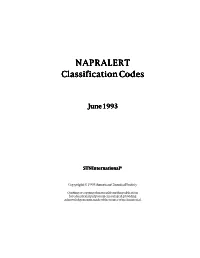

NAPRALERT Classification Codes

NAPRALERT Classification Codes June 1993 STN International® Copyright © 1993 American Chemical Society Quoting or copying of material from this publication for educational purposes is encouraged, providing acknowledgement is made of the source of such material. Classification Codes in NAPRALERT The NAPRALERT File contains classification codes that designate pharmacological activities. The code and a corresponding textual description are searchable in the /CC field. To be comprehensive, both the code and the text should be searched. Either may be posted, but not both. The following tables list the code and the text for the various categories. The first two digits of the code describe the categories. Each table lists the category described by codes. The last table (starting on page 56) lists the Classification Codes alphabetically. The text is followed by the code that also describes the category. General types of pharmacological activities may encompass several different categories of effect. You may want to search several classification codes, depending upon how general or specific you want the retrievals to be. By reading through the list, you may find several categories related to the information of interest to you. For example, if you are looking for information on diabetes, you might want to included both HYPOGLYCEMIC ACTIVITY/CC and ANTIHYPERGLYCEMIC ACTIVITY/CC and their codes in the search profile. Use the EXPAND command to verify search terms. => S HYPOGLYCEMIC ACTIVITY/CC OR 17006/CC OR ANTIHYPERGLYCEMIC ACTIVITY/CC OR 17007/CC 490 “HYPOGLYCEMIC”/CC 26131 “ACTIVITY”/CC 490 HYPOGLYCEMIC ACTIVITY/CC ((“HYPOGLYCEMIC”(S)”ACTIVITY”)/CC) 6 17006/CC 776 “ANTIHYPERGLYCEMIC”/CC 26131 “ACTIVITY”/CC 776 ANTIHYPERGLYCEMIC ACTIVITY/CC ((“ANTIHYPERGLYCEMIC”(S)”ACTIVITY”)/CC) 3 17007/CC L1 1038 HYPOGLYCEMIC ACTIVITY/CC OR 17006/CC OR ANTIHYPERGLYCEMIC ACTIVITY/CC OR 17007/CC 2 This search retrieves records with the searched classification codes such as the ones shown here. -

Supporting Information

Electronic Supplementary Material (ESI) for Metallomics. This journal is © The Royal Society of Chemistry 2019 Supporting information for Metabolomic and proteomic changes induced by growth inhibitory concentrations of copper in the biofilm-forming marine bacterium Pseudoalteromonas lipolytica Laurie Favre,a Annick Ortalo-Magné,a,* Lionel Kerloch,a Carole Pichereaux,b,c Benjamin Misson,d Jean-François Brianda, Cédric Garnierd and Gérald Culiolia,* a Université de Toulon, MAPIEM EA 4323, Toulon, France. b Fédération de Recherche FR3450, Agrobiosciences, Interaction et Biodiversité (AIB), CNRS, Toulouse, France.. c Institut de Pharmacologie et de Biologie Structurale, IPBS, Université de Toulouse, CNRS, UPS, Toulouse, France. d Univ de Toulon, Aix Marseille Univ, CNRS, IRD, MIO UM 110, Mediterranean Institute of Oceanography, La Garde, France. Detailed description of the experimental protocol used for Cu chemical speciation. Differential pulse anodic striping voltammetry (DPASV) measurements were performed to assess Cu chemical speciation in both VNSS and MB medium. All voltammetric measurements were performed using a PGSTAT12 potentiostat (EcoChemie, The Netherlands) equipped with a Metrohm 663 VA stand (Metrohm, Switzerland) on an Hg drop electrode. Analysis of the voltammetric peaks' (after 2nd derivative transformation) and construction of the pseudo- polarograms were performed automatically using ECDSoft software. The experimental procedure adapted from Nicolau et al. (2008) and Bravin et al. (2012) is explained briefly below. Pseudo-polarographic measurements (DPASV measurement with Edep from -1.0 to 0.0V by steps of 100 mV, using a deposition time of 30s) were initially performed on UV-irradiated seawater (collected outside the Toulon bay: ambient Cu concentration of 2.5 nM) at pH < 2 (by adding HNO3 Suprapur grade, Merck), to determine the deposition potential (Edep -0.35V) corresponding to the electrochemically "labile" Cu fraction (sum of free Cu ions plus inorganically bound Cu) (Figure S2).