South Yorkshire Tenants’ Association

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IL Combo Ndx V2

file IL COMBO v2 for PDF.doc updated 13-12-2006 THE INDUSTRIAL LOCOMOTIVE The Quarterly Journal of THE INDUSTRIAL LOCOMOTIVE SOCIETY COMBINED INDEX of Volumes 1 to 7 1976 – 1996 IL No.1 to No.79 PROVISIONAL EDITION www.industrial-loco.org.uk IL COMBO v2 for PDF.doc updated 13-12-2006 INTRODUCTION and ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This “Combo Index” has been assembled by combining the contents of the separate indexes originally created, for each individual volume, over a period of almost 30 years by a number of different people each using different approaches and methods. The first three volume indexes were produced on typewriters, though subsequent issues were produced by computers, and happily digital files had been preserved for these apart from one section of one index. It has therefore been necessary to create digital versions of 3 original indexes using “Optical Character Recognition” (OCR), which has not proved easy due to the relatively poor print, and extremely small text (font) size, of some of the indexes in particular. Thus the OCR results have required extensive proof-reading. Very fortunately, a team of volunteers to assist in the project was recruited from the membership of the Society, and grateful thanks are undoubtedly due to the major players in this exercise – Paul Burkhalter, John Hill, John Hutchings, Frank Jux, John Maddox and Robin Simmonds – with a special thankyou to Russell Wear, current Editor of "IL" and Chairman of the Society, who has both helped and given encouragement to the project in a myraid of different ways. None of this would have been possible but for the efforts of those who compiled the original individual indexes – Frank Jux, Ian Lloyd, (the late) James Lowe, John Scotford, and John Wood – and to the volume index print preparers such as Roger Hateley, who set a new level of presentation which is standing the test of time. -

South Yorkshire

INDUSTRIAL HISTORY of SOUTH RKSHI E Association for Industrial Archaeology CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION 6 STEEL 26 10 TEXTILE 2 FARMING, FOOD AND The cementation process 26 Wool 53 DRINK, WOODLANDS Crucible steel 27 Cotton 54 Land drainage 4 Wire 29 Linen weaving 54 Farm Engine houses 4 The 19thC steel revolution 31 Artificial fibres 55 Corn milling 5 Alloy steels 32 Clothing 55 Water Corn Mills 5 Forging and rolling 33 11 OTHER MANUFACTUR- Windmills 6 Magnets 34 ING INDUSTRIES Steam corn mills 6 Don Valley & Sheffield maps 35 Chemicals 56 Other foods 6 South Yorkshire map 36-7 Upholstery 57 Maltings 7 7 ENGINEERING AND Tanning 57 Breweries 7 VEHICLES 38 Paper 57 Snuff 8 Engineering 38 Printing 58 Woodlands and timber 8 Ships and boats 40 12 GAS, ELECTRICITY, 3 COAL 9 Railway vehicles 40 SEWERAGE Coal settlements 14 Road vehicles 41 Gas 59 4 OTHER MINERALS AND 8 CUTLERY AND Electricity 59 MINERAL PRODUCTS 15 SILVERWARE 42 Water 60 Lime 15 Cutlery 42 Sewerage 61 Ruddle 16 Hand forges 42 13 TRANSPORT Bricks 16 Water power 43 Roads 62 Fireclay 16 Workshops 44 Canals 64 Pottery 17 Silverware 45 Tramroads 65 Glass 17 Other products 48 Railways 66 5 IRON 19 Handles and scales 48 Town Trams 68 Iron mining 19 9 EDGE TOOLS Other road transport 68 Foundries 22 Agricultural tools 49 14 MUSEUMS 69 Wrought iron and water power 23 Other Edge Tools and Files 50 Index 70 Further reading 71 USING THIS BOOK South Yorkshire has a long history of industry including water power, iron, steel, engineering, coal, textiles, and glass. -

Gatley, David Alan (1984) 16-19 Year Olds in Three Northern New Towns: Their Political, Economic and Social Outlooks and Aspirations

Gatley, David Alan (1984) 16-19 Year Olds in Three Northern New Towns: Their Political, Economic and Social Outlooks and Aspirations. Masters thesis, Sunderland Polytechnic. Downloaded from: http://sure.sunderland.ac.uk/6362/ Usage guidelines Please refer to the usage guidelines at http://sure.sunderland.ac.uk/policies.html or alternatively contact [email protected]. 16-19 YEAR OLDS IN THREE NORTHERN NEW THEIR POLITICAL, ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL OUTLOOKS AND ASPIRATIONS A thesis submitted to the Council for National Academic Awards in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Philosophy. by David Alan Gatley Sunderland Polytechnic August 1984 DEDICATION To my nieces and nephews. ii DECLARATION While registered for the degree of Master of Philosophy, for which the present submission is made, the author has not been a registered candidate for any other award, either of the C.N.A.A. or any University. The work was carried out in the Department of Teaching Studies at Sunderland Polytechnic between September 1982 and August 1984, and is believed to be wholly original1 except where due reference is made. Ah advanced course of study on the principles of educational and sociological research was also undertaken in partial fulfilment of the requirements of this degree. iii CONTENTS Chapters 1. Introduction 1 2. Literature Review 32 3. The Main Characteristics of the Sample 62 4. Education in the Three New Towns 80 5. Young People Employment, Unemployment and 116 Youth Training 6. Young People in their Local Communities 145 7. The Political Attitudes of Young People 185 8. Conclusions 247 Bibliography 257 Appendices A. -

4.-Report-Of-South-Yorkshire-Police

' The Police Committee Special Sub-Committee at their meeting on 24 January 19.85 approved this report and recommended that it should be presented to the Police Committee for their approval. In doing so, they wish to place on record their appreciation and gratitude to all the members of the County Council's Department of Administration who have assisted and advised the Sub-Committee in their inquiry or who have been involved in the preparation of this report, in particular Anne Conaty (Assistant Solicitor), Len Cooksey (Committee Administrator), Elizabeth Griffiths (Secretary to the Deputy County Clerk) and David Hainsworth (Deputy County Clerk). (Councillor Dawson reserved his position on the report and the Sub-Committee agreed to consider a minority report from him). ----------------------- ~~- -1- • Frontispiece "There were many lessons to be learned from the steel strike and from the Police point of view the most valuable lesson was that to be derived from maintaining traditional Police methods of being firm but fair and resorting to minimum force by way of bodily contact and avoiding the use of weapons. My feelings on Police strategy in industrial disputes and also those of one of my predecessors, Sir Philip Knights, are encapsulated in our replies to questions asked of us when we appeared before the House of Commons Select Committee on Employment on Wednesday 27 February 1980. I said 'I would hope that despite all the problems that we have you will still allow us to have our discretion and you will not move towards the Army, CRS-type policing, or anything like that. -

Industrial Railways July 2019

The R.C.T.S. is a Charitable Incorporated Organisation registered with The Charities Commission Registered No. 1169995. THE RAILWAY CORRESPONDENCE AND TRAVEL SOCIETY PHOTOGRAPHIC LIST LIST 7 - INDUSTRIAL RAILWAYS JULY 2019 The R.C.T.S. is a Charitable Incorporated Organisation registered with The Charities Commission Registered No. 1169995. www.rcts.org.uk VAT REGISTERED No. 197 3433 35 R.C.T.S. PHOTOGRAPHS – ORDERING INFORMATION The Society has a collection of images dating from pre-war up to the present day. The images, which are mainly the work of late members, are arranged in in fourteen lists shown below. The full set of lists covers upwards of 46,900 images. They are : List 1A Steam locomotives (BR & Miscellaneous Companies) List 1B Steam locomotives (GWR & Constituent Companies) List 1C Steam locomotives (LMS & Constituent Companies) List 1D Steam locomotives (LNER & Constituent Companies) List 1E Steam locomotives (SR & Constituent Companies) List 2 Diesel locomotives, DMUs & Gas Turbine Locomotives List 3 Electric Locomotives, EMUs, Trams & Trolleybuses List 4 Coaching stock List 5 Rolling stock (other than coaches) List 6 Buildings & Infrastructure (including signalling) List 7 Industrial Railways List 8 Overseas Railways & Trams List 9 Miscellaneous Subjects (including Railway Coats of Arms) List 10 Reserve List (Including unidentified images) LISTS Lists may be downloaded from the website http://www.rcts.org.uk/features/archive/. PRICING AND ORDERING INFORMATION Prints and images are now produced by ZenFolio via the website. Refer to the website (http://www.rcts.org.uk/features/archive/) for current prices and information. NOTES ON THE LISTS 1. Colour photographs are identified by a ‘C’ after the reference number. -

Private Owner Wagons Index

PRIVATE OWNER WAGONS & TANKERS INDEX [MAINLY PRE – 1948] COMPILED BY JOE GREAVES This index alphabetically lists references in books to private owner railway wagons and tankers by company name. Each company is listed by an abbreviation of the book’s author and its page number. Coal Merchants who ran wagons are also included. Most of the references include either a photograph or drawing of the wagon. It is not intended to be a comprehensive list of every private owner wagon built, merely of those that have appeared in books since 1969. Where there is only a description of the wagon or notes about the owner, but no photo or drawing, the reference has * next to it. Some of these [IP1/147* & JA/184* particularly] are as little as just a name with no location or any other details. Locations of the companies are included unless it is obvious from the name on the wagon. If there is no location listed, particularly with the Welsh wagons, the name is the location (please check with an atlas). In Bill Hudson’s first two books (BH1 & BH2), his index lists wagons by plate (ie photo) number rather than page. In this index, they are by page number. Wagons shown in the prefaces are listed by Roman numerals, eg BH2/vi. For his third & fourth volumes (BH3 & BH4), there are no page numbers so the references are to plates not pages. Richard Tourret’s books are listed as RT, then RT2. There is no ‘RT1’. Entries are usually by surname or place, for example ‘City of Nottingham’ is under ‘N’ not ‘C’ (but North, South, East or West are under N, S, E or W.) If there is likely to be any uncertainty, the name may be listed twice, eg, Griffith Thomas is under ‘G’ and ‘T’. -

The Pennine Lower and Middle Coal Measures Formations of the Barnsley District

The Pennine Lower and Middle Coal Measures formations of the Barnsley district Geology & Landscape Southern Britain Programme Internal Report IR/06/135 BRITISH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY GEOLOGY & LANDSCAPE SOUTHERN BRITAIN PROGRAMME INTERNAL REPORT IR/06/135 The Pennine Lower and Middle Coal Measures formations of the Barnsley district The National Grid and other R D Lake Ordnance Survey data are used with the permission of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. Editor Licence No: 100017897/2005. E Hough Keywords Pennine Lower Coal Measures Formation; Pennine Middle Coal Measures Formation; Barnsley; Pennines. Bibliographical reference R D LAKE & E HOUGH (EDITOR).. 2006. The Pennine Lower and Middle Coal Measures formations of the Barnsley district. British Geological Survey Internal Report,IR/06/135. 47pp. Copyright in materials derived from the British Geological Survey’s work is owned by the Natural Environment Research Council (NERC) and/or the authority that commissioned the work. You may not copy or adapt this publication without first obtaining permission. Contact the BGS Intellectual Property Rights Section, British Geological Survey, Keyworth, e-mail [email protected]. You may quote extracts of a reasonable length without prior permission, provided a full acknowledgement is given of the source of the extract. Maps and diagrams in this book use topography based on Ordnance Survey mapping. © NERC 2006. All rights reserved Keyworth, Nottingham British Geological Survey 2006 BRITISH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY The full range of Survey publications is available from the BGS British Geological Survey offices Sales Desks at Nottingham, Edinburgh and London; see contact details below or shop online at www.geologyshop.com Keyworth, Nottingham NG12 5GG The London Information Office also maintains a reference 0115-936 3241 Fax 0115-936 3488 collection of BGS publications including maps for consultation. -

Poldark’S Pulling Power RTS STUDENT TELEVISION AWARDS 2016 3 JUNE 1:00Pm BFI Southbank, London SE1 8XT

May 2016 Poldark’s pulling power RTS STUDENT TELEVISION AWARDS 2016 3 JUNE 1:00pm BFI Southbank, London SE1 8XT www.rts.org.uk Journal of The Royal Television Society May 2016 l Volume 53/5 From the CEO I am delighted to one of 2015’s breakout hits, Poldark, insights into the growing importance announce the head- featured as the latest subject of the of analytics in television. I think it’s line speakers at our RTS’s “Anatomy of a hit” strand. fair to say that everyone who attended London Conference The evening was a great success as will have returned to their desks the on 27 September. the four panellists each gave their next day armed with some informa- Steve Burke, CEO of own, unique insight into how the tion that they could act on. NBCUniversal, is our series was brought to the small screen. Thanks to all of those who partici- keynote speaker, and is joined by: I’d like to thank each one of them pated and to the producers of an RTS President Sir Peter Bazalgette; and I am very grateful to Boyd Hilton impressive event, and to Torin Doug- Ofcom CEO Sharon White; Kevin for being such an informed chair. las for chairing with such professional MacLellan, Chair of NBCUniversal Quite a lot of Poldark fans stayed after- poise. International; Tom Mockridge, CEO wards to talk to the panel privately. Inside there is lots to read, but don’t of Virgin Media and David Abraham, It was a genuinely inspiring evening miss Stuart Kemp’s piece on Chan- CEO of Channel 4. -

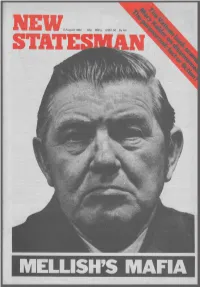

6August 1982

6 August 1982 The- real. mafia man vu lga r-minde dvand very much the he would not seek re-election) the Ber- Bob Mellish ha-sretired from the ", supporter of whoever is his boss at the mondsey Labour Party selected their sesre- Labour Party amid a blaze of . moment'. Mellish was an eager placeman, tary Peter Tatchell as the prospective- can- accusations of 'mafia tactics' and 'hit and has wanted 'desperately to be a Cabinet didate.' Mellish effectively 'blackmailed- Minister responsible for London and for Michael FOQt into. a public repudiation of lists' levelled at the London and housing. His political campaigning -and Tatchell. Although the meeting was secret BermondseyLabour Parties. personal platform has spanned a narrow at the time, the particulars are nQWknown. DUNCAN CAMPBELLreports ON Mt field, from orthodox catholic politics and Mellish threatened that he would resign' Mellish's career. sympathy for the Iberian dictatorships to forthwith if Tatchell were endorsed as can- persistent racialist attitudes-to immigrants didate by the Labour National Executive, HAD HE NOT RESIGNED from the and appeals to free East Enders like and would then campaign against him. Labour Party on Monday, Bob Mellish gangster Charlie Richardson and 'Scarface'. FOQt eventually _agreed to Mellish's de- faced certain expulsion this Friday at the Parsons (a well known robber in the mands leading to. the enormous and hands of West Lewisha:m Labour Party, 1950s). He has been associated; to his em- damaging public row last November. ' where he lives. This was because of his barrassment, .with three corrupt _ busi- Two. -

The C Onflict of Interest Issue and the B Ritish House of Commons

The Conflict of Interest Issue and the B ritish House of Commons: A Practical Problem and a Conceptual Conundrum by Sandra Ann Williams Thesis submitted fo r the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Bedford College, University of London ProQuest Number: 10098551 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest. ProQuest 10098551 Published by ProQuest LLC(2016). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 ABSTRACT In 1974 the House of Commons agreed by Resolution to take the un precedented step of introducing a Register of Members' Interests. It also converted the convention that a Member should declare any personal pecuniary interest relevant to any debate or proceeding into a rule of the House. These measures were designed to avoid actual or apparent conflict between a Member's private interests and his public duties as an MR. The experience of the House in dealing with c o n flic t of inte rest, and the problems of defining, identifying and regulating this phenom enon, have, hitherto, been discussed only peripherally in academic l i t e r ature on Parliament. -

Appendix a Governments and Ministers Responsible For

APPENDIX A GOVERNMENTS AND MINISTERS RESPONSIBLE FOR BROADCASTING, 1954-80 Party Prime Minister Date of Appointment Postmaster-General Date of Appointment Conservative Sir Winston Churchill 26 October 1951 Earl De La Warr 5 November 1951 Sir Anthony Eden 6 April 1955 Dr Charles Hill 7 April 1955 Harold Macmillan 10 January 1957 Ernest Marples 16 January 1957 Reginald Bevins 22 October 1959 Sir Alec Douglas-Home 18 October 1963 Vl 0 Labour Harold Wilson 16 October 1964 Anthony Wedgwood Benn 19 October 1964 0- Edward Short 4 July 1966 Roy Mason 6 April 1968 John Stonehouse 1 July 1968 Minister of Posts and Telecommunications John Stonehouse 1 October 1969 Conservative Edward Heath 19 June 1970 Christopher Chataway 24 June 1970 Sir John Eden 7 April 1972 Labour Harold Wilson 4 March 1974 Anthony Wedgwood Benn 7 March 1974 Home Secretary Roy Jenkins 30 March 1974 Merlyn Rees 10 September 1976 James Callaghan 5 April 1976 Conservative Margaret Thatcher 4 May 1979 William Whitelaw 5 May 1979 APPENDIX B MEMBERS OF THE AUTHORITY, 1954-80 Chairmen Terms of Office Background Sir Kenneth Clark KCB 4 August 1954-31 August 1957 Former Director of the National Gallery and Surveyor (later Lord Clark OM,CH) of the King's Pictures; Chairman, Arts Council of Great Britain Sir Ivone Kirkpatrick GCB,GCMG 7 November 1957-6 November 1962 Former UK High Commissioner for Germany; former Permanent Under-Secretary, Foreign Office Rt Hon. Lord Hill of Luton PC 1 July 1963-30 August 1967 Former Secretary, British Medical Association; former Postmaster-General; former Chancellor of Duchy of Lancaster; former Minister of Housing & Local Government and Minister for Welsh Affairs Rt Hon. -

North East History Volume 44 East

north east history north north east history volume 44 east history N orth Volume 44 2013 E ast H istory 44 2013 Consett: a photo essay Peter Brabban Popular Politics Project Final Event March 2013 Politics in the Piggery: Chartism in the Ouseburn 1838-1848 Mike Greatbatch An Uneasy relationship? Labour and the Suffragettes The north east labour history society holds regular meetings on in the North East Sue Jones a wide variety of subjects. The society welcomes new members. We have an increasingly busy web-site at www.nelh.org Competition, conflict and regulation: the Foyboatmen Supporters are welcome to contribute to discussions 1900-1950 Adrian Osler Their Geordies and Ours- Part 1 Dave Harker journal of the north east labour history society Volume 44 http://nelh.org/ 2013 journal of the north east labour history society north east history north east Volume 44 2013 history ISSN 14743248 © 2013 NORTHUMBERLAND Printed by Azure Printing Units 1 F & G Pegswood Industrial Estate Pegswood Morpeth TYNE & Northumberland WEAR NE61 6HZ Tel: 01670 510271 DURHAM TEESSIDE journal of the north east labour history society www.nelh.net 1 north east history Contents Editorial 5 Covers Notes & Acknowledgements 9 Notes on Contributors 11 Mapping Popular Politics Project Consett: a photo essay Peter Brabban 15 Politics in the Piggery: Chartism in the Mike Greatbatch 33 Ouseburn 1838-1848 Parentages of Martin Jude and John Burnett Edward Davies 62 Oral History Interviews Liz O’Donnell 66 Thomas Wilson: the Great Hoarder Maria Goulding and 73 Judith MacSwaine