Rural Determinations Decennial Review Analysis of Communities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

APPENDIX a Document Index

APPENDIX A Document Index Alaska Aviation System Plan Document Index - 24 April 2008 Title Reference # Location / Electronic and/or Paper Copy Organization / Author Pub. Date Other Comments / Notes / Special Studies AASP's Use 1-2 AASP #1 1 WHPacific / Electronic & Paper Copies DOT&PF / TRA/Farr Jan-86 Report plus appendix AASP #2 DOT&PF / TRA-BV Airport 2 WHPacific / Electronic & Paper Copies Mar-96 Report plus appendix Consulting Statewide Transportation Plans Use 10 -19 2030 Let's Get Moving! Alaska Statewide Long-Range http://dot.alaska.gov/stwdplng/areaplans/lrtpp/SWLRTPHo 10 DOT&PF Feb-08 Technical Appendix also available Transportation Policy Plan Update me.shtml Regional Transportation Plans Use 20-29 Northwest Alaska Transportation Plan This plan is the Community Transportation Analysis -- there is 20 http://dot.alaska.gov/stwdplng/areaplans/nwplan.shtml DOT&PF Feb-04 also a Resource Transportation Analysis, focusing on resource development transportation needs Southwest Alaska Transportation Plan 21 http://dot.alaska.gov/stwdplng/areaplans/swplan.shtml DOT&PF / PB Consult Sep-04 Report & appendices available Y-K Delta Transportation Plan 22 http://dot.alaska.gov/stwdplng/areaplans/ykplan.shtml DOT&PF Mar-02 Report & appendices available Prince William Sound Area Transportation Plan 23 http://dot.alaska.gov/stwdplng/areaplans/pwsplan.shtml DOT&PF / Parsons Brinokerhoff Jul-01 Report & relevant technical memos available Southeast Alaska Transportation Plan http://www.dot.state.ak.us/stwdplng/projectinfo/ser/newwave 24 DOT&PF Aug-04 -

The Stocked Lakes of Donnelly Training Area Getting There

The Stocked Lakes of Donnelly Training Area Getting There... The Alaska Department of Fish and Game stocks About 8 miles south of Delta Junction, at MP 257.6 has no road access, but it can be reached by 16 lakes on Donnelly Training Area. Depending on Fishing Tips Richardson Highway, Meadows Road provides floatplane in the summer. During winter, you can the lake, you can fish for rainbow trout, Arctic char, access to most of the Donnelly Training Area reach Koole Lake on the winter trail. Cross the Arctic grayling, landlocked salmon, and lake trout. In some of the deeper lakes, there are naturally stocked lakes. Bullwinkle, Sheefish, Bolio, Luke, Tanana River and follow the trail, which starts at MP occurring populations of lake chub, sculpin, Arctic Mark, North Twin, South Twin, No Mercy, 306.2 Richardson Highway near Birch Lake. Koole Anglers fish from the bank on most of these lakes grayling, and longnose sucker. Of the hundreds of Rockhound, and Doc lakes all lie within a few miles Lake is stocked with rainbow trout. ADF&G has a because there is fairly deep water near shore. accessible lakes that exist on Donnelly Training Area, of Meadows Road. trail map to Koole Lake. Contact us at 459-7228 to Inflatable rafts, float tubes, and canoes can also be only these 16 are deep enough to stock game fishes. obtain a map. used, but the lakes are too small for motorized You can use a variety of tackle to catch these stocked boats, and there are no launch facilities. fish. -

2020 Alaska Interagency Mobilization Guide Table of Contents

Table of Contents Chapter 10 – Objectives, Policy, and Scope of Operations 1 Mission Statement 1 Alaska Interagency Mobilization Guide 1 Total Mobility 2 Priorities 2 Scope of Operation 2 National Response Framework (NRF) 2 Office of Foreign Disaster Assistance (OFDA) 2 Northwest Wildland Fire Protection Agreement (Northwest Compact) 2 State Disaster Declarations / Division of Homeland Security (DHS) and Emergency Services (ES) 2 Mobilization / Demobilization 2 Work/Rest, Length of Assignment, Days Off and Extensions 3 Incident Operations Driving 3 Initial Response Definition 3 Invasive Plant/Seed Prevention 3 Wildland Fire Entrapment/Fatality 3 National Resources 3 Notification of Commitment of National Resources 3 Unable to Fill (UTF) Procedure 4 Standard Cubes, Weight, and Gear Policy for Personnel 4 Cost Coding 4 Fire Numbers 5 National Fire Preparedness Plan 6 National Multi-Agency Coordinating Group (NMAC) 9 Alaska Wildland Fire Coordinating Group (AWFCG) 9 Alaska Multi-Agency Coordinating Group (Alaska MAC or AMAC) 10 Incident Support Organization (ISO) 10 Mobilization Procedures for Military Assets 10 Established Resource Ordering Process 10 Civilian Support 10 Demobilization Procedures 10 International Operations 10 Ordering Channels 11 Geographic Area Coordination Centers (GACCs) 11 Alaska Coordination and Dispatch Centers 11 Agency Resource Providers in Alaska 12 Dispatch Center Call 12 Placing Requests with AICC 12 Ordering Procedures 12 Transferring Incidents between Centers in CAD and ROSS 13 Support to Border Fires 14 Non-Incident Related Ordering 14 Agreements 14 International Agreements 14 Interagency Agreements 15 Chapter 20 – Overhead and Teams 19 Mobilization and Demobilization 19 Travel 19 BLM Alaska Fire Service (AFS) Requests 19 State of Alaska Division of Forestry (DOF) Requests 20 2020 Alaska Interagency Mobilization Guide Table of Contents U.S. -

Fort Greely, Alaska

DCN: 9873 FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY Ground-Based Midcourse Defense (GMD) Fort Greely, Alaska Presented by: Mr. Tom Devanney Deputy Program Director Ground-Based Midcourse Defense 26 April 2004 Draft Deliberative Document For Discussion Purposes Only DO NOT RELEASE Under FOIA FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY Mission And Tasks “The Defense Department… Shall Proceed With Plans to Deploy a Set of Initial Missile Defense Capabilities Beginning in 2004.” President George W. Bush NSPD-23, 16 DEC 02 BMDS Mission • Provide Missile Defense Capabilities to COCOMs Tasks • Build, Test, and Verify an Initial Defensive Operations Capability • Place the BMDS on Alert • Execute Concurrent Testing and Defensive Operations • Continue Development to Incrementally Improve Capability BottomBottom Line:Line: FieldField anan InitialInitial MissileMissile DefenseDefense CapabilityCapability TEAMTEAM GMD Forging America’s Shield 7/7/2005 6:35 PM FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY GM-04-01-02106-R27-(TABS Installation Familiar Brief)-(04-26-04)-(U) 2 FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY MDA – Fort Greely • Public Law 107-20: (July 24, 2001) – Sec. 1207: The Secretary of Defense may retain all or a portion of Fort Greely, AK as the Secretary deems necessary to meet military operations logistics and personnel support requirements for missile defense. • Memo - SECDEF to Director, BMDO (Now MDA): – Delegates authority to retain portions of Fort Greely, AK to meet Missile Defense Requirements to Director, BMDO • Memo for DASA (I&H) Attn: Mr. Paul Johnson: (10 Aug 01) – BMDO determined that -

Chapter 70 Dispatch Directory

Chapter 70 Dispatch Directory Chapter - 70 – Dispatch Organization Directory CHAPTER 70 - FIRE ORGANIZATION DIRECTORY ALASKA DISPATCH OFFICES QUICK REFERENCE PRIMARY PAGE CENTER NUMBER NUMBER Alaska Interagency Coordination Center (907) 356-5680 68 Chugach National Forest Dispatch (907) 743-9433 74 Delta Area Dispatch (907) 895-2106 71 Fairbanks Area Dispatch (907) 451-2623 71 Galena Zone Dispatch (907) 656-9650 69 Kenai Interagency Dispatch Center (907) 260-4232 69 Mat-Su Area Dispatch (907) 761-6240 72 State Logistics Center (907) 451-2680 70 Southwest (McGrath) Dispatch (when open) (907) 524-3367 72 Tok Area Dispatch (907) 883-1406 73 Tongass National Forest Dispatch (907) 228-6211 74 Upper Yukon / Tanana / Military Zone Dispatch (907) 356-5555 70 Center Valdez-Copper River Area Dispatch (907) 822-8626 73 67 2020 Alaska Interagency Mobilization Guide Chapter 70 Dispatch Directory ALASKA AREA COORDINATION AND DISPATCH CENTERS Alaska Interagency Coordination Center ALASKA INTERAGENCY TELEPHONE NUMBER: (907) 356-5680 COORDINATION CENTER 1541 Gaffney Road P.O. Box 35005 TOLL FREE: (800) 237-3633 Ft. Wainwright, Alaska 99703-5005 NIGHT/24-HOUR: (907) 356-5680 Email: BLM_AK_ACCMOB_dispatch @blm.gov FACSIMILE NUMBER: (907) 356 -5678 or BLM_AK_ACCINT_dispatch (907) 356-5698 @blm.gov AREA OFFICE NAME/TITLE CITY/STATE CODE PHONE CROWE, Ray Ft. Wainwright, AK 907 356-5677 Center Manager SHOOK, Hilary “ “ 356-5685 Assistant Center Manager RUBIN, Katie “ “ 356-5682 State Logistics Coordinator HUMPHREY, Jennifer “ “ 356-5690 Tactical/Aircraft Coordinator -

United States Army Garrison, Alaska Integrated Natural Resources Management Plan

United States Army Garrison, Alaska Integrated Natural Resources Management Plan September 2020 This page left intentionally blank. Executive Summary The US Army Garrison (USAG) Alaska Integrated Natural Resources Management Plan (INRMP) establishes policies, programs, prescriptions, projects, and procedures that the Army uses to manage natural resources on training lands in Alaska. The INRMP contains goals and specific objectives necessary to (1) sustain “no net loss” in the capability of military lands to support mission requirements, (2) support stewardship of natural resources, (3) ensure compliance with applicable environmental laws, and (4) maximize public access within the constraints of the military mission while protecting public safety and conserving the environment. This INRMP reflects the mutual agreement of the USAG Alaska, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) and Alaska Department of Fish and Game (ADFG) concerning the conservation of the natural resources under their respective legal authorities. The INRMP references other related Army natural resource planning documents, including the Integrated Wildland Fire Management Plan (IWFMP). INRMP STATUS The initial Fort Wainwright and Fort Greely INRMPs were signed and implemented in 1998. These INRMPs were revised in 2002, in 2007 and in 2013 due to substantial changes in natural resources management proposals, as well as agency, tribal, and public stakeholder comments. The National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) process was used to meet the Department of Defense’s INRMP public review requirements for the initial Fort Wainwright and Fort Greely INRMPs in 1998. Due to substantive changes in the 2002 and 2007 Fort Wainwright INRMP revisions, public review was again accomplished through the NEPA process. -

6 Transportation Analysis

Interior Alaska Transportation Plan November 2010 6 Transportation Analysis 6.1 Highway Transportation Analysis The highway transportation analysis considers the following factors: Roadway Operations: planning assessment based on highway traffic forecasts. Safety: crash data assessment, special interest areas, safety plans (Highway Safety Improvement Program (HSIP), SHSP), and predictive safety improvements. Roadway Conditions and System Needs: roadway system needs, planned improvements, resource needs (i.e. pipeline), railroad (grade separation), and local community access. Maintenance & Operations: maintenance stations, deferred and preventive maintenance, and maintenance management systems. Pavement Preservation and Management: pavement preservation, pavement management, and weight restrictions. Security: border crossing and the Alyeska Pipeline. Tourism Enhancements: scenic byways and rest areas (signage and accessibility). 6.1.1 Roadway Capacity Using the 2030 forecast traffic volumes, a comprehensive roadway capacity evaluation was completed for all of the major rural highways. A planning level assessment based on the existing highway characteristics and 2030 traffic forecasts revealed no major roadway capacity constraints. Under long-term conditions, all roadway facilities within the study area will continue to operate at a LOS C or better, with most facilities forecast to operate at LOS A and B. As discussed in Section Error! Reference source not found. Highway Traffic Forecasts, the potential impacts of future resource and economic development would have the greatest impact on rural highway operations. However, based on the future traffic operations assessment assuming a relatively average (i.e. medium growth) annual growth in highway traffic, traffic volumes would have to double or even triple on average in order to impact the capacity needs in the system. -

Chapter 70 Dispatch Directory

Chapter 70 Dispatch Directory Chapter - 70 – Dispatch Organization Directory CHAPTER 70 - FIRE ORGANIZATION DIRECTORY ALASKA DISPATCH OFFICES QUICK REFERENCE PRIMARY PAGE CENTER NUMBER NUMBER Alaska Interagency Coordination Center (907) 356-5680 71 Chugach National Forest Dispatch (907) 743-9433 77 Galena Zone Dispatch (907) 656-9650 72 Kenai Interagency Dispatch Center (907) 260-4232 72 Mat-Su Area Dispatch (907)-761-6240 75 Northern Forestry Dispatch Center (907)-451-2690 73 Southwest (McGrath) Dispatch (when open) (907) 524-3367 75 Tongass National Forest Dispatch (907) 228-6211 77 Upper Yukon / Tanana / Military Zone Dispatch (907) 356-5555 73 Center Valdez-Copper River Area Dispatch (907) 822-8626 76 71 2021 Alaska Interagency Mobilization Guide Chapter 70 Dispatch Directory ALASKA AREA COORDINATION AND DISPATCH CENTERS Alaska Interagency Coordination Center ALASKA INTERAGENCY TELEPHONE NUMBER: (907) 356-5680 COORDINATION CENTER 1541 Gaffney Road P.O. Box 35005 TOLL FREE: (800) 237-3633 Ft. Wainwright, Alaska 99703-5005 NIGHT/24-HOUR: (907) 356-5680 Email: BLM_AK_ACCMOB_dispatch @blm.gov FACSIMILE NUMBER: (907) 356 -5678 or BLM_AK_ACCINT_dispatch (907) 356-5698 @blm.gov AREA OFFICE NAME/TITLE CITY/STATE CODE PHONE CROWE, Ray Ft. Wainwright, AK 907 356-5677 Center Manager SHOOK, Hilary “ “ 356-5685 DeputyCenter Manager RUBIN, Katie “ “ 356-5682 State Logistics Coordinator HUMPHREY, Jennifer “ “ 356-5690 Tactical/Aircraft Coordinator ELLIOT, Jennifer “ “ 356-5681 Aircraft Coordinator COOK, April “ “ 356-5687 Equipment/Supply Coordinator DECK, Brooke “ “ 356-5684 Overhead/Crews Coordinator BRANSON, GaBriella “ “ 356-5671 Intelligence Coordinator STRADER, Heidi “ “ 356-5691 Predictive Services Meteorologist STEVENS, Eric “ “ 356-5691 Predictive Services Meteorologist MOORE, Chris “ “ 356-5673 Fire Behavior Analyst 72 2021 Alaska Interagency Mobilization Guide Chapter 70 Dispatch Directory Kenai Interagency Dispatch Center State of Alaska Kenai-Kodiak Area FIRELINE: (907) 260-4100 U.S. -

IATA Airports

IATA Codes for the United States of America N.B. To check the official, current database of IATA Codes see: http://www.iata.org/publications/Pages/code-search.aspx City State IATA Code Airport Name Web Address Aberdeen SD ABR Aberdeen Proving APG Phillips Army Air Field Grounds(Aberdeen) Abilene TX ABI Abilene DYS Dyess Air Force Base Abingdon VJI Virginia Highlands Ada ADT Ada Municipal Adak Island AK ADK Adrian ADG Lenawee County Afton AFO Afton Municipal Afton NRI Grand Lake Regional Aiken AIK Aiken Municipal Ainsworth ANW Ainsworth Municipal Akhiok AKK Akhiok Akiachak AK KKI Akiak AK AKI Akron AKC Akron Fulton International Akron AKO Colorado Plains Regional Akuton AK KQA City State IATA Code Airport Name Web Address Alakanuk AK AUK Alamogordo NM ALM Alamogordo HMN Holloman Air Force Base Alamosa CO ALS Albany OR CVO Albany NY ALB Albany OR QWY Albany GA NAB Albany NAS Albany ABY Southwest Georgia Regional Albert Lea AEL Albert Lea Municipal Albuquerque NM ABQ Aleknagik AK WKK Aleneva AED Aleneva Alexander City ALX Thomas C Russell Field Alexandria LA AEX Alexandria AXN Chandler Field Alexandria ESF Esler Regional Alexandria Bay AXB Maxson Airfield Algona AXG Algona Municipal Alice ALI Alice International Aliceville AIV George Downer Allakaket AK AET Alliance NE AIA Alma AMN Gratiot Community Alpena MI APN Alpine ALE Alpine Casparis 2 City State IATA Code Airport Name Web Address Municipal Alton/St Louis ALN St Louis Regional Altoona PA AOO Altoona–Blair County http://flyaltoona.com/ Airport Altus LTS Altus Air Force Base Altus AXS -

Chapter 3 Affected Environment

CHAPTER 3 AFFECTED ENVIRONMENT 3.1 INTRODUCTION . 3-1 3.2 AIR QUALITY . 3-7 3.3 GEOLOGY RESOURCES . 3-17 3.4 SOIL RESOURCES . 3-23 3.5 SURFACE WATER . 3-29 3.6 GROUNDWATER . 3-41 3.7 WETLANDS . 3-47 3.8 VEGETATION . 3-53 3.9 WILDLIFE AND FISHERIES . 3-65 3.10 THREATENED OR ENDANGERED SPECIES AND SPECIES OF CONCERN . 3-91 3.11 FIRE MANAGEMENT . 3-97 3.12 CULTURAL RESOURCES . 3-105 3.13 SOCIOECONOMICS . 3-117 3.14 PUBLIC ACCESS AND RECREATION . 3-139 3.15 SUBSISTENCE . 3-149 3.16 NOISE . 3-159 3.17 HUMAN HEALTH AND SAFETY . 3-165 3.18 ENVIRONMENTAL JUSTICE . 3-177 3.19 INFRASTRUCTURE . 3-183 Transformation Environmental Impact Statement Final U.S. Army Alaska CHAPTER 3 AFFECTED ENVIRONMENT 3.1 INTRODUCTION 3.1.1 Organization This section of the Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) provides description of the existing conditions at Fort Wainwright (including the Main Post, and the Tanana Flats and Yukon Training Areas), Donnelly Training Area (including nearby training areas at Gerstle River and Black Rapids), and Fort Richardson (Figure 3.1.a). The conditions at each post are described within subsections of each environmental category. 3-1 Transformation Environmental Impact Statement Final U.S. Army Alaska Section Category Page Number 3.2 Air Quality 3-7 3.3 Geology Resources 3-17 3.4 Soil Resources (Issue D, Maneuver Impacts) 3-23 3.5 Surface Water 3-29 3.6 Groundwater 3-41 3.7 Wetlands (Issue C, Wildlife and Habitat; Issue D, 3-47 Maneuver Impacts) 3.8 Vegetation 3-53 3.9 Wildlife and Fisheries (Issue C, Wildlife and Habitat) 3-65 3.10 -

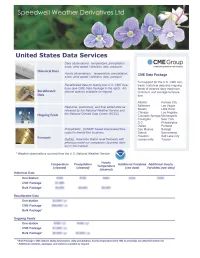

Information on US Data

United States Data Services Observation Attribute Information Daily maximum temperature (day = d) = the highest temperature observed over a 24-hour period from 0000d to 2359d LST Daily minimum temperature (day = d) = the lowest temperature observed over a 24-hour period from 0000d to 2359d LST Daily precipitation (day = d) = the total liquid equivalent observed over a 24-hour period from 0000d to 2359d LST Note: LST = local standard time Delivery Schedule Delivery options include: FTP (push / pull), Speedwell web site, and e-mail - Cleaned data (previous day) to be delivered daily by 7am Eastern Time - National Climate Data Center quality controlled data available as monthly deliveries approximately 2 weeks after the month Formatting Speedwell has the ability to provide data in a number of different formats as well as provide data per user specifications. Most reasonable requests can be accommodated without the need for additional fees. Speedwell Cleaned Data Speedwell Recalibrated Data Sets Cleaned data is data that has been processed to fill missing Speedwell Recalibrated Data Sets re-base historical data to values and correct erroneous observations. The end result is a current site location, conditions and instrumentation by adjust- dataset that is ready to be use for analysis. ing for historical temperature discontinuities. This is critical to a complete understanding of the behavior of a weather reference Speedwell’s proprietary cleaning methodologies use a mixture site. Recalibration does not involve detrending of automated processing to flag possible errors followed by manual inspection. In relation to the cleaning of daily data*, Historical Recalibration tests that are performed include: • Cleaned time series • Recalibrated time series • How does the obs. -

Federal Register/Vol. 70, No. 183/Thursday, September 22, 2005/Rules and Regulations

Federal Register / Vol. 70, No. 183 / Thursday, September 22, 2005 / Rules and Regulations 55531 We prepared a regulatory evaluation § 39.13 [Amended] Unsafe Condition of the estimated costs to comply with I 2. The Federal Aviation (d) This AD results from a report of fatigue this AD and placed it in the AD docket. Administration (FAA) amends § 39.13 cracks that initiated in the duct structure of See the ADDRESSES section for a location by adding the following new the ram air outlet, which is adjacent to the to examine the regulatory evaluation. airworthiness directive (AD): hydraulics compartment. The FAA is issuing this AD to prevent fatigue cracks in the duct List of Subjects in 14 CFR Part 39 2005–19–22 Airbus: Amendment 39–14287. structure of the ram air outlet, which could Air transportation, Aircraft, Aviation Docket No. FAA–2005–22486; Directorate Identifier 2004–NM–219–AD. lead to hot air damage and consequent loss safety, Incorporation by reference, of function of the hydraulics systems. Safety. Effective Date Compliance: (e) You are responsible for Adoption of the Amendment (a) This AD becomes effective October 7, having the actions required by this AD 2005. performed within the compliance times I Accordingly, under the authority Affected ADs specified, unless the actions have already delegated to me by the Administrator, been done. the FAA amends 14 CFR part 39 as (b) None. Applicability: (c) This AD applies to Airbus Modification follows: Model A330–322, –341, and –342 airplanes; (f) Before the airplane accumulates 12,000 and Model A340–211, –212, –213, –311, PART 39—AIRWORTHINESS –312, and –313 airplanes; certificated in any total flight cycles, or within 60 days after the DIRECTIVES category; as identified in Airbus Service effective date of this AD, whichever occurs later: Modify the ram air outlet ducts of the I 1.