November 2010

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FY2014 Aviation - Deferred Maintenance

FY2014 Aviation - Deferred Maintenance Project Cost Project Description Location House Project Title (1,000's) (City) District Brush cutting at 3 Interior Aviation airports back to original clearing Interior Interior Airport Brush-Cutting 90.0 limits: Stevens Village, Beaver and Fort Yukon – to improve Aviation 39 aviation safety District Southwest District Lighting Southwest 35 - 37 150.0 Various lighting replacement and repair in Southwest District Repairs District Brush Cutting on RSA 2/20 50.0 Brush cutting with excavator & hand brushing Klawock 34 Repair airport fencing (at At Cordova Airport, repair or replace 900 LF of deteriorated Valdez 100.0 6 Cordova) fencing. District Y-K Delta Airports 500.0 Contract for gravel stockpile for surfacing repairs Various 36 - 38 Brush Cutting on RSA 8/26 50.0 Brush Cutting on RSA 8/26 Haines 34 Replace equipment fuel storage tanks at (6) Interior Aviation airports; Ruby, Rampart, Lake Minchumina, Hughes, Chalkyitsik, Interior Fuel Storage Tank Bettles; in order to burn ultra low sulfur diesel, provide for 200.0 Aviation 38 - 39 Repair/Replacement economical bulk fuel delivery, and store enough fuel onsite to operate snow removal equipment for a normal winter season. Dist Enhance security through fencing and lights to prevent loss of expensive fuel due to theft. New Access Gate 35.0 Replace access gate Skagway 32 Valdez Repair airport fencing (at Nome) 50.0 At Nome Airport, repair or replace 250 LF of fencing. 6 District Old Harbor Airport 150.0 Replace deteriorated surface course Old harbor 35 -

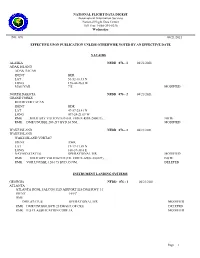

Page 1 NATIONAL FLIGHT DATA DIGEST Aeronautical Information

NATIONAL FLIGHT DATA DIGEST Aeronautical Information Services National Flight Data Center Toll Free 1-866-295-8236 Wednesday NO. 076 04/21/2021 EFFECTIVE UPON PUBLICATION UNLESS OTHERWISE NOTED BY AN EFFECTIVE DATE NAVAIDS ALASKA NFDD 076 - 1 04/21/2021 ADAK ISLAND ADAK TACAN IDENT BER LAT 51-52-16.43 N LONG 176-40-26.8 W MAG VAR 7 E MODIFIED NORTH DAKOTA NFDD 076 - 2 04/21/2021 GRAND FORKS RED RIVER TACAN IDENT RDR LAT 47-57-25.41 N LONG 097-24-21.69 W RMK ....MILITARY VALIDATED (FIL FIDEX-RDR-200033).... NOTE RMK DME UNUSBL 209-219 BYD 30 NM. MODIFIED WAKE ISLAND NFDD 076 - 3 04/21/2021 WAKE ISLAND WAKE ISLAND VORTAC IDENT AWK LAT 19-17-11.69 N LONG 166-37-38.4 E NAVAID STATUS OPERATIONAL IFR MODIFIED RMK ....MILITARY VALIDATED (FIL FIDEX-AWK-200127).... NOTE RMK VOR UNUSBL 120-175 BYD 35 NM. DELETED INSTRUMENT LANDING SYSTEMS GEORGIA NFDD 076 - 1 04/21/2021 ATLANTA ATLANTA RGNL FALCON FLD AIRPORT ILS/DME RWY 31 IDENT I-FFC DME DME STATUS OPERATIONAL IFR MODIFIED RMK DME UNUSBL BYD 25 DEGS L OF CRS. DELETED RMK ILS CLASSIFICATION CODE IA. MODIFIED Page 1 AIR TRAFFIC CONTROL TOWERS MICHIGAN NFDD 076 - 1 04/21/2021 SAGINAW MBS INTL-ATCT IDENT MBS FREQUENCIES FREQUENCY 118.45 DELETED FREQUENCY USE ASR DELETED APCH/DEP CALL GREAT LAKES FREQUENCY 120.95 DELETED FREQUENCY USE APCH/S DEP/S DELETED AIRPORT ALASKA NFDD 076 - 1 04/21/2021 ATQASUK ATQASUK EDWARD BURNELL SR MEML AIRPORT ( ATK ) 50044.5A LATITUDE - 70-28-01.6 N LONGITUDE - 157-26-08.4 W RMK COLD TEMPERATURE RESTRICTED AIRPORT. -

(Asos) Implementation Plan

AUTOMATED SURFACE OBSERVING SYSTEM (ASOS) IMPLEMENTATION PLAN VAISALA CEILOMETER - CL31 November 14, 2008 U.S. Department of Commerce National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration National Weather Service / Office of Operational Systems/Observing Systems Branch National Weather Service / Office of Science and Technology/Development Branch Table of Contents Section Page Executive Summary............................................................................ iii 1.0 Introduction ............................................................................... 1 1.1 Background.......................................................................... 1 1.2 Purpose................................................................................. 2 1.3 Scope.................................................................................... 2 1.4 Applicable Documents......................................................... 2 1.5 Points of Contact.................................................................. 4 2.0 Pre-Operational Implementation Activities ............................ 6 3.0 Operational Implementation Planning Activities ................... 6 3.1 Planning/Decision Activities ............................................... 7 3.2 Logistic Support Activities .................................................. 11 3.3 Configuration Management (CM) Activities....................... 12 3.4 Operational Support Activities ............................................ 12 4.0 Operational Implementation (OI) Activities ......................... -

Notice of Adjustments to Service Obligations

Served: May 12, 2020 UNITED STATES OF AMERICA DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION OFFICE OF THE SECRETARY WASHINGTON, D.C. CONTINUATION OF CERTAIN AIR SERVICE PURSUANT TO PUBLIC LAW NO. 116-136 §§ 4005 AND 4114(b) Docket DOT-OST-2020-0037 NOTICE OF ADJUSTMENTS TO SERVICE OBLIGATIONS Summary By this notice, the U.S. Department of Transportation (the Department) announces an opportunity for incremental adjustments to service obligations under Order 2020-4-2, issued April 7, 2020, in light of ongoing challenges faced by U.S. airlines due to the Coronavirus (COVID-19) public health emergency. With this notice as the initial step, the Department will use a systematic process to allow covered carriers1 to reduce the number of points they must serve as a proportion of their total service obligation, subject to certain restrictions explained below.2 Covered carriers must submit prioritized lists of points to which they wish to suspend service no later than 5:00 PM (EDT), May 18, 2020. DOT will adjudicate these requests simultaneously and publish its tentative decisions for public comment before finalizing the point exemptions. As explained further below, every community that was served by a covered carrier prior to March 1, 2020, will continue to receive service from at least one covered carrier. The exemption process in Order 2020-4-2 will continue to be available to air carriers to address other facts and circumstances. Background On March 27, 2020, the President signed the Coronavirus Aid, Recovery, and Economic Security Act (the CARES Act) into law. Sections 4005 and 4114(b) of the CARES Act authorize the Secretary to require, “to the extent reasonable and practicable,” an air carrier receiving financial assistance under the Act to maintain scheduled air transportation service as the Secretary deems necessary to ensure services to any point served by that air carrier before March 1, 2020. -

APPENDIX a Document Index

APPENDIX A Document Index Alaska Aviation System Plan Document Index - 24 April 2008 Title Reference # Location / Electronic and/or Paper Copy Organization / Author Pub. Date Other Comments / Notes / Special Studies AASP's Use 1-2 AASP #1 1 WHPacific / Electronic & Paper Copies DOT&PF / TRA/Farr Jan-86 Report plus appendix AASP #2 DOT&PF / TRA-BV Airport 2 WHPacific / Electronic & Paper Copies Mar-96 Report plus appendix Consulting Statewide Transportation Plans Use 10 -19 2030 Let's Get Moving! Alaska Statewide Long-Range http://dot.alaska.gov/stwdplng/areaplans/lrtpp/SWLRTPHo 10 DOT&PF Feb-08 Technical Appendix also available Transportation Policy Plan Update me.shtml Regional Transportation Plans Use 20-29 Northwest Alaska Transportation Plan This plan is the Community Transportation Analysis -- there is 20 http://dot.alaska.gov/stwdplng/areaplans/nwplan.shtml DOT&PF Feb-04 also a Resource Transportation Analysis, focusing on resource development transportation needs Southwest Alaska Transportation Plan 21 http://dot.alaska.gov/stwdplng/areaplans/swplan.shtml DOT&PF / PB Consult Sep-04 Report & appendices available Y-K Delta Transportation Plan 22 http://dot.alaska.gov/stwdplng/areaplans/ykplan.shtml DOT&PF Mar-02 Report & appendices available Prince William Sound Area Transportation Plan 23 http://dot.alaska.gov/stwdplng/areaplans/pwsplan.shtml DOT&PF / Parsons Brinokerhoff Jul-01 Report & relevant technical memos available Southeast Alaska Transportation Plan http://www.dot.state.ak.us/stwdplng/projectinfo/ser/newwave 24 DOT&PF Aug-04 -

Election District Report

Fiscal Year 1992 Election District Report Legislative Finance Division P.O. BoxWF Juneau, Alaska 99811 (907) 465-3795 TABLE OF CONTENTS ELECTION DISTRICT PAGE NUMBER Summaries ........................................................... III - VI 01 Ketchikan - Wrangell - Petersburg. 1 02 Inside Passage . .. 7 03 Baranof - Chichagof. .. 11 04 Juneau. .. 15 05 Kenai - Cook Inlet . .. 21 06 Prince William Sound . .. 25 07 - 15 Anchorage .............................................................. 31 16 Matanuska - Susitna . .. 61 17 Interior Highways. .. 67 18 Southeast North Star Borough. .. 71 19 - 21 Fairbanks . .. 73 22 North Slope ~- Kotzebue ..................................................... 79 23 Norton Sound ........................................................... 83 24 Interior Rivers . 89 25 Lower Kuskokwim ......... ~.............................................. 93 26 Bristol Bay - Aleutian Islands . 97 27 Kodiak - East Alaska Peninsula ... .. 101 99 Statewide & Totals. .. 107 I II FY92 CAPITAL BUDGET /REAPPROPRIATIONS (CH 96, SLA 91) - AFTER VETOES ELECTION CAPITAL CAPITAL REAPPROP REAPPROP DISTRICT GENFUNDS TOTAL FUNDS GENFUNDS TOTAL FUNDS TOTALS 1 21,750.1 35,266.3 0.0 0.0 35,266.3 2 8,223.8 15,195.6 0.0 0.0 15,195.6 3 3,524.8 6,446.1 0.0 0.0 6,446.1 4 8,397.2 19,387.0 1,360.0 1,360.0 20,747.0 5 11,885.0 16,083.9 0.0 0.0 16,083.9 6 5,315.0 14,371.1 0.0 0.0 14,371.1 7 - 15 73,022.9 99,167.9 -95.3 -95.3 99,072.6 16 13,383.0 66,817.2 -20.0 -20.0 66,797.2 17 6,968.5 39,775.5 0.0 0.0 39,775.5 18 2,103.6 2,753.6 0.0 0.0 2,753.6 -

The Stocked Lakes of Donnelly Training Area Getting There

The Stocked Lakes of Donnelly Training Area Getting There... The Alaska Department of Fish and Game stocks About 8 miles south of Delta Junction, at MP 257.6 has no road access, but it can be reached by 16 lakes on Donnelly Training Area. Depending on Fishing Tips Richardson Highway, Meadows Road provides floatplane in the summer. During winter, you can the lake, you can fish for rainbow trout, Arctic char, access to most of the Donnelly Training Area reach Koole Lake on the winter trail. Cross the Arctic grayling, landlocked salmon, and lake trout. In some of the deeper lakes, there are naturally stocked lakes. Bullwinkle, Sheefish, Bolio, Luke, Tanana River and follow the trail, which starts at MP occurring populations of lake chub, sculpin, Arctic Mark, North Twin, South Twin, No Mercy, 306.2 Richardson Highway near Birch Lake. Koole Anglers fish from the bank on most of these lakes grayling, and longnose sucker. Of the hundreds of Rockhound, and Doc lakes all lie within a few miles Lake is stocked with rainbow trout. ADF&G has a because there is fairly deep water near shore. accessible lakes that exist on Donnelly Training Area, of Meadows Road. trail map to Koole Lake. Contact us at 459-7228 to Inflatable rafts, float tubes, and canoes can also be only these 16 are deep enough to stock game fishes. obtain a map. used, but the lakes are too small for motorized You can use a variety of tackle to catch these stocked boats, and there are no launch facilities. fish. -

Chugiak-Eagle River Comprehensive Plan Update

Chugiak-Eagle River Comprehensive Plan Update December 2006 Planning Department Municipality of Anchorage CHUGIAK-EAGLE RIVER COMPREHENSIVE PLAN UPDATE Adopted December 12, 2006 Assembly Ordinance 2006-93(S-1) Prepared by the Physical Planning Division Planning Department Municipality of Anchorage Mark Begich, Mayor C HUGIAK-EAGLE R IVER C OMPREHENSIVE P LAN U PDATE -ii- MUNICIPALITY OF ANCHORAGE Assembly Dan Sullivan, Chair Debbie Ossiander, Vice-Chair Paul Bauer Janice Shamberg Chris Birch Ken Stout Dan Coffey Allan Tesche Anna Fairclough Dick Traini Pamela Jennings Planning and Zoning Commission Toni Jones, Chair Art Isham, Vice-Chair Lamar Cotten Nancy Pease Jim Fredrick Bruce Phelps Andrew Josephson Thomas Vincent Wang Jim Palmer Planning Department Tom Nelson, Director Physical Planning Division Cathy Hammond, Supervisor Tom Davis Van Le Susan Perry Parks and Recreation Department Eagle River John Rodda Information Technology Department GIS Services Lisa Ameen Jeff Anderson C HUGIAK-EAGLE R IVER C OMPREHENSIVE P LAN U PDATE -iii- Chugiak-Eagle River Comprehensive Plan Update Citizens’ Advisory Committee Jim Arnesen, Eklutna, Inc. Andy Brewer, South Fork Community Council Susan Browne, Eagle River Valley Community Council Michael Curry, Eklutna, Inc. Gail Dial, Chugiak, Birchwood, Eagle River Rural Road Service Area Judith Fetherolf, Eagle River Community Council Bob Gill, South Fork Community Council Susan Gorski, Chugiak-Eagle River Chamber of Commerce Bobbie Gossweiler, Eagle River Community Council Lexi Hill, Chugiak-Eagle River Parks & Recreation Board of Supervisors Charlie Horsman, Eagle River Community Council Val Jokela, Birchwood Community Council Ted Kinney, Chugiak Community Council Linda Kovac, Chugiak Community Council Diane Payne, Birchwood Community Council Tim Potter, Eklutna, Inc. -

State of Alaska Itb Number 2515H029 Amendment Number One (1)

STATE OF ALASKA ITB NUMBER 2515H029 AMENDMENT NUMBER ONE (1) AMENDMENT ISSUING OFFICE: Department of Transportation & Public Facilities Statewide Contracting & Procurement P.O. Box 112500 (3132 Channel Drive, Room 145) Juneau, Alaska 99811-2500 THIS IS NOT AN ORDER DATE AMENDMENT ISSUED: February 9, 2015 ITB TITLE: De-icing Chemicals ITB OPENING DATE AND TIME: February 27, 2015 @ 2:00 PM Alaska Time The following changes are required: 1. Attachment A, DOT/PF Maintenance Stations identifying the address and contact information and is added to this ITB. This is a mandatory return Amendment. Your bid may be considered non-responsive and rejected if this signed amendment is not received [in addition to your bid] by the bid opening date and time. Becky Gattung Procurement Officer PHONE: (907) 465-8949 FAX: (907) 465-2024 NAME OF COMPANY DATE PRINTED NAME SIGNATURE ITB 2515H029 - De-icing Chemicals ATTACHMENT A DOT/PF Maintenance Stations SOUTHEAST REGION F.O.B. POINT Contact Name: Contact Phone: Cell: Juneau: 6860 Glacier Hwy., Juneau, AK 99801 Eric Wilkerson 465-1787 723-7028 Gustavus: Gustavus Airport, Gustavus, AK 99826 Brad Rider 697-2251 321-1514 Haines: 720 Main St., Haines, AK 99827 Matt Boron 766-2340 314-0334 Hoonah: 700 Airport Way, Hoonah, AK 99829 Ken Meserve 945-3426 723-2375 Ketchikan: 5148 N. Tongass Hwy. Ketchikan, AK 99901 Loren Starr 225-2513 617-7400 Klawock: 1/4 Mile Airport Rd., Klawock, AK 99921 Tim Lacour 755-2229 401-0240 Petersburg: 288 Mitkof Hwy., Petersburg, AK 99833 Mike Etcher 772-4624 518-9012 Sitka: 605 Airport Rd., Sitka, AK 99835 Steve Bell 966-2960 752-0033 Skagway: 2.5 Mile Klondike Hwy., Skagway, AK 99840 Missy Tyson 983-2323 612-0201 Wrangell: Airport Rd., Wrangell, AK 99929 William Bloom 874-3107 305-0450 Yakutat: Yakutat Airport, Yakutat, AK 99689 Robert Lekanof 784-3476 784-3717 1 of 6 ITB 2515H029 - De-icing Chemicals ATTACHMENT A DOT/PF Maintenance Stations NORTHERN REGION F.O.B. -

Area Management Report for the Sport Fisheries of Northern Cook Inlet, 2017–2018

Fishery Management Report No. 20-04 Area Management Report for the Sport Fisheries of Northern Cook Inlet, 2017–2018 by Samantha Oslund Sam Ivey and Daryl Lescanec January 2020 Alaska Department of Fish and Game Divisions of Sport Fish and Commercial Fisheries Symbols and Abbreviations The following symbols and abbreviations, and others approved for the Système International d'Unités (SI), are used without definition in the following reports by the Divisions of Sport Fish and of Commercial Fisheries: Fishery Manuscripts, Fishery Data Series Reports, Fishery Management Reports, and Special Publications. All others, including deviations from definitions listed below, are noted in the text at first mention, as well as in the titles or footnotes of tables, and in figure or figure captions. Weights and measures (metric) General Mathematics, statistics centimeter cm Alaska Administrative all standard mathematical deciliter dL Code AAC signs, symbols and gram g all commonly accepted abbreviations hectare ha abbreviations e.g., Mr., Mrs., alternate hypothesis HA kilogram kg AM, PM, etc. base of natural logarithm e kilometer km all commonly accepted catch per unit effort CPUE liter L professional titles e.g., Dr., Ph.D., coefficient of variation CV meter m R.N., etc. common test statistics (F, t, χ2, etc.) milliliter mL at @ confidence interval CI millimeter mm compass directions: correlation coefficient east E (multiple) R Weights and measures (English) north N correlation coefficient cubic feet per second ft3/s south S (simple) r foot ft west W covariance cov gallon gal copyright degree (angular) ° inch in corporate suffixes: degrees of freedom df mile mi Company Co. -

Invitation to Bid Invitation Number 2519H037

INVITATION TO BID INVITATION NUMBER 2519H037 RETURN THIS BID TO THE ISSUING OFFICE AT: Department of Transportation & Public Facilities Statewide Contracting & Procurement P.O. Box 112500 (3132 Channel Drive, Suite 350) Juneau, Alaska 99811-2500 THIS IS NOT AN ORDER DATE ITB ISSUED: January 24, 2019 ITB TITLE: De-icing Chemicals SEALED BIDS MUST BE SUBMITTED TO THE STATEWIDE CONTRACTING AND PROCUREMENT OFFICE AND MUST BE TIME AND DATE STAMPED BY THE PURCHASING SECTION PRIOR TO 2:00 PM (ALASKA TIME) ON FEBRUARY 14, 2019 AT WHICH TIME THEY WILL BE PUBLICLY OPENED. DELIVERY LOCATION: See the “Bid Schedule” DELIVERY DATE: See the “Bid Schedule” F.O.B. POINT: FINAL DESTINATION IMPORTANT NOTICE: If you received this solicitation from the State’s “Online Public Notice” web site, you must register with the Procurement Officer listed on this document to receive subsequent amendments. Failure to contact the Procurement Officer may result in the rejection of your offer. BIDDER'S NOTICE: By signature on this form, the bidder certifies that: (1) the bidder has a valid Alaska business license, or will obtain one prior to award of any contract resulting from this ITB. If the bidder possesses a valid Alaska business license, the license number must be written below or one of the following forms of evidence must be submitted with the bid: • a canceled check for the business license fee; • a copy of the business license application with a receipt date stamp from the State's business license office; • a receipt from the State’s business license office for -

Forest Health Conditions in Alaska 2020

Forest Service U.S. DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE Alaska Region | R10-PR-046 | April 2021 Forest Health Conditions in Alaska - 2020 A Forest Health Protection Report U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, State & Private Forestry, Alaska Region Karl Dalla Rosa, Acting Director for State & Private Forestry, 1220 SW Third Avenue, Portland, OR 97204, [email protected] Michael Shephard, Deputy Director State & Private Forestry, 161 East 1st Avenue, Door 8, Anchorage, AK 99501, [email protected] Jason Anderson, Acting Deputy Director State & Private Forestry, 161 East 1st Avenue, Door 8, Anchorage, AK 99501, [email protected] Alaska Forest Health Specialists Forest Service, Forest Health Protection, http://www.fs.fed.us/r10/spf/fhp/ Anchorage, Southcentral Field Office 161 East 1st Avenue, Door 8, Anchorage, AK 99501 Phone: (907) 743-9451 Fax: (907) 743-9479 Betty Charnon, Invasive Plants, FHM, Pesticides, [email protected]; Jessie Moan, Entomologist, [email protected]; Steve Swenson, Biological Science Technician, [email protected] Fairbanks, Interior Field Office 3700 Airport Way, Fairbanks, AK 99709 Phone: (907) 451-2799, Fax: (907) 451-2690 Sydney Brannoch, Entomologist, [email protected]; Garret Dubois, Biological Science Technician, [email protected]; Lori Winton, Plant Pathologist, [email protected] Juneau, Southeast Field Office 11175 Auke Lake Way, Juneau, AK 99801 Phone: (907) 586-8811; Fax: (907) 586-7848 Isaac Dell, Biological Scientist, [email protected]; Elizabeth Graham, Entomologist, [email protected]; Karen Hutten, Aerial Survey Program Manager, [email protected]; Robin Mulvey, Plant Pathologist, [email protected] State of Alaska, Department of Natural Resources Division of Forestry 550 W 7th Avenue, Suite 1450, Anchorage, AK 99501 Phone: (907) 269-8460; Fax: (907) 269-8931 Jason Moan, Forest Health Program Coordinator, [email protected]; Martin Schoofs, Forest Health Forester, [email protected] University of Alaska Fairbanks Cooperative Extension Service 219 E.