University Microfilms International 300 N

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Donahue Poetry Collection Prints 2013.004

Donahue Poetry Collection Prints 2013.004 Quantity: 3 record boxes, 2 flat boxes Access: Open to research Acquisition: Various dates. See Administrative Note. Processed by: Abigail Stambach, June 2013. Revised April 2015 and May 2015 Administrative Note: The prints found in this collection were bought with funds from the Carol Ann Donahue Memorial Poetry endowment. They were purchased at various times since the 1970s and are cataloged individually. In May 2013, it was transferred to the Sage Colleges Archives and Special Collections. At this time, the collection was rehoused in new archival boxes and folders. The collection is arranged in call number order. Box and Folder Listing: Box Folder Folder Contents Number Number Control Folder 1 1 ML410 .S196 C9: Sports et divertissements by Erik Satie 1 2 N620 G8: Word and Image [Exhibition] December 1965, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum 1 3 N6494 .D3 H8: Dada Manifesto 1949 by Richard Huelsenbeck 1 4 N6769 .G3 A32: Kingling by Ian Gardner 1 5 N7153 .T45 A3 1978X: Drummer by Andre Thomkins 1 6 NC790 .B3: Landscape of St. Ives, Huntingdonshire by Stephen Bann 1 7 NC1820 .R6: Robert Bly Poetry Reading, Unicorn Bookshop, Friday, April 21, 8pm 1 8 NC1850 .P28 P3 V.1: PN2 Experiment 1 9 NC1850 .P28 P3 V.2: PN2 Experiment 1 10 NC1850 .P28 P3 V.4: PN2 Experiment 1 11 NC1850 .P28 P3 V.5: PN2 Experiment 1 12 NC1850 .P28 P3 V.6: PN2 Experiment 1 13 NC1850 .P28 P3 V.7: PN2 Experiment 1 14 NC1850 .P28 P3 V.9: PN2 Experiment 1 15 NC1850 .P28 P3 V.10: PN2 Experiment 1 16 NC1850 .P28 P3 V.12: PN2 Experiment 1 17 NC1850 .P28 P3 V.13: PN2 Experiment 1 18 NC1860 .N4: Peace Post Card no. -

Exile, Diplomacy and Texts: Exchanges Between Iberia and the British Isles, 1500–1767

Exile, Diplomacy and Texts Intersections Interdisciplinary Studies in Early Modern Culture General Editor Karl A.E. Enenkel (Chair of Medieval and Neo-Latin Literature Westfälische Wilhelms-Universität Münster e-mail: kenen_01@uni_muenster.de) Editorial Board W. van Anrooij (University of Leiden) W. de Boer (Miami University) Chr. Göttler (University of Bern) J.L. de Jong (University of Groningen) W.S. Melion (Emory University) R. Seidel (Goethe University Frankfurt am Main) P.J. Smith (University of Leiden) J. Thompson (Queen’s University Belfast) A. Traninger (Freie Universität Berlin) C. Zittel (Ca’ Foscari University of Venice / University of Stuttgart) C. Zwierlein (Freie Universität Berlin) volume 74 – 2021 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/inte Exile, Diplomacy and Texts Exchanges between Iberia and the British Isles, 1500–1767 Edited by Ana Sáez-Hidalgo Berta Cano-Echevarría LEIDEN | BOSTON This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 license, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided no alterations are made and the original author(s) and source are credited. Further information and the complete license text can be found at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ The terms of the CC license apply only to the original material. The use of material from other sources (indicated by a reference) such as diagrams, illustrations, photos and text samples may require further permission from the respective copyright holder. This volume has been benefited from financial support of the research project “Exilio, diplomacia y transmisión textual: Redes de intercambio entre la Península Ibérica y las Islas Británicas en la Edad Moderna,” from the Agencia Estatal de Investigación, the Spanish Research Agency (Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad). -

Governing Biosafety in India: the Relevance of the Cartagena Protocol

Belfer Center for Science & International Affairs Governing Biosafety in India: The Relevance of the Cartagena Protocol Aarti Gupta 2000-24 October 2000 Global Environmental Assessment Project Environment and Natural Resources Program CITATION, CONTEXT, AND PROJECT ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This paper may be cited as: Gupta, Aarti. “Governing Biosafety in India: The Relevance of the Cartagena Protocol.” Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs (BCSIA) Discussion Paper 2000-24, Environment and Natural Resources Program, Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University, 2000. Available at http://environment.harvard.edu/gea. No further citation is allowed without permission of the author. Comments are welcome and may be directed to the author at the Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, John F. Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University, 79 John F. Kennedy Street, Cambridge, MA 02138; Email aarti_gupta@ harvard.edu. The Global Environmental Assessment project is a collaborative team study of global environmental assessment as a link between science and policy. The Team is based at Harvard University. The project has two principal objectives. The first is to develop a more realistic and synoptic model of the actual relationships among science, assessment, and management in social responses to global change, and to use that model to understand, critique, and improve current practice of assessment as a bridge between science and policy making. The second is to elucidate a strategy of adaptive assessment and policy for global environmental problems, along with the methods and institutions to implement such a strategy in the real world. The Global Environmental Assessment (GEA) Project is supported by a core grant from the National Science Foundation (Award No. -

Directx™ 12 Case Studies

DirectX™ 12 Case Studies Holger Gruen Senior DevTech Engineer, 3/1/2017 Agenda •Introduction •DX12 in The Division from Massive Entertainment •DX12 in Anvil Next Engine from Ubisoft •DX12 in Hitman from IO Interactive •DX12 in 'Game AAA' •AfterMath Preview •Nsight VSE & DirectX12 Games •Q&A www.gameworks.nvidia.com 2 Agenda •Introduction •DX12 in The Division from Massive Entertainment •DX12 in Anvil Next Engine from Ubisoft •DX12 in Hitman from IO Interactive •DX12 in 'Game AAA' •AfterMath Preview •Nsight VSE & DirectX12 Games •Q&A www.gameworks.nvidia.com 3 Introduction •DirectX 12 is here to stay • Games do now support DX12 & many engines are transitioning to DX12 •DirectX 12 makes 3D programming more complex • see DX12 Do’s & Don’ts in developer section on NVIDIA.com •Goal for this talk is to … • Hear what talented developers have done to cope with DX12 • See what developers want to share when asked to describe their DX12 story • Gain insights for your own DX11 to DX12 transition www.gameworks.nvidia.com 4 Thanks & Credits •Carl Johan Lejdfors Technical Director & Daniel Wesslen Render Architect - Massive •Jonas Meyer Lead Render Programmer & Anders Wang Kristensen Render Programmer - Io-Interactive •Tiago Rodrigues 3D Programmer - Ubisoft Montreal www.gameworks.nvidia.com 5 Before we really start … •Things we’ll be hearing about a lot • Memory Managment • Barriers • Pipeline State Objects • Root Signature and Shader Bindings • Multiple Queues • Multi threading If you get a chance check out the DX12 presentation from Monday’s ‘The -

The BG News February 16, 1990

Bowling Green State University ScholarWorks@BGSU BG News (Student Newspaper) University Publications 2-16-1990 The BG News February 16, 1990 Bowling Green State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news Recommended Citation Bowling Green State University, "The BG News February 16, 1990" (1990). BG News (Student Newspaper). 5043. https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news/5043 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University Publications at ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in BG News (Student Newspaper) by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@BGSU. FEATURED PHOTOS ICERS HOST FLAMES BG News photographers BG looks to clinch Q show off their best Friday Mag third-place CCHA finish Sports p.9 The Nation *s Best College Newspaper Weather Friday Vol.72 Issue 84 February 16,1990 Bowling Green, Ohio High48c The BG News Low 30° BRIEFLY Hall arson Plant's layoffs delayed arrest made Automotive sales slump, but Chrysler pushes back plan CAMPUS TOLEDO (AP) - Indefinite uled to shut down for a week. by Michelle Matheson layoffs of 724 workers at Chrysler "I know a lot of The two plants, which manufac- staff writer ture Cherokees and Grand Wa- Map grant received: The Corp.'s Jeep plants have been people think the goneers, employ 5,300 people. pushed back two weeks, and some Chrysler has said the layoffs are University's map-making class will A resident of Founders Quadrangle was ar- workers said Thursday they hope plant is eventually soon be charting a new course thanks the layoffs can be avoided all due to slumping automotive sales. -

Toronto /Busan 2019

TORONTO /BUSAN 2019 RESIN THE OTHER LAMB HOPE THE OTHER LAMB 4-5 COMING SOON 20-21 HOPE 6-7 SCREENING SCHEDULE 22 LINE-UP RESIN 8-9 CONTACTS 23 THE PERFECT PATIENT 10-11 DANIEL 12-13 VALHALLA 14-15 ANOTHER ROUND 16-17 CHARTER 18-19 INDEX SPECIAL PRESENTATIONS THE OTHER LAMB - Directed by Małgorzata Szumowska Selected for the Special Presentations section at this year’s festival, THE OTHER LAMB is the first English language feature from highly acclaimed director, Małgorzata Szumowska. What’s more, the film will be screening later this year in Competition at both San Sebastian International Film Festival and London Film Festival. A prolific filmmaker, Małgorzata Szumowska won The Silver Bear at the 2015 Berlinale for her Polish language film BODY, and the Grand Jury Prize for MUG at the 2018 Berlinale. THE OTHER LAMB stars Raffey Cassidy (VOX LUX, 2018), Michiel Huisman (THE HAUNTING OF HILL HOUSE, 2018), and Denise Gough (COLETTE, 2018). Featured on the 2017 “Black List and Blood List”, THE OTHER LAMB is written by the award-winning Australian screenwriter Catherine S. McMullen. The film’s producers include Academy Award® nominee David Lancaster and Stephanie Wilcox of Rumble Films, producers of amongst others DRIVE (2011), WHIPLASH (2014), NIGHTCRAWLER (2014) and EYE IN THE SKY (2016). THE OTHER LAMB is a haunting and nightmarish tale that tells the story of Selah (RAFFEY CASSIDY), a young girl born into an alternative religion known as the Flock. The members of the Flock – all women and female children– live in a rural compound, and are led by one man, known only as Shepherd (MICHIEL HUISMAN). -

Industry Guide Focus Asia & Ttb / April 29Th - May 3Rd Ideazione E Realizzazione Organization

INDUSTRY GUIDE FOCUS ASIA & TTB / APRIL 29TH - MAY 3RD IDEAZIONE E REALIZZAZIONE ORGANIZATION CON / WITH CON IL CONTRIBUTO DI / WITH THE SUPPORT OF IN COLLABORAZIONE CON / IN COLLABORATION WITH CON LA PARTECIPAZIONE DI / WITH THE PARTICIPATION OF CON IL PATROCINIO DI / UNDER THE PATRONAGE OF FOCUS ASIA CON IL SUPPORTO DI/WITH THE SUPPORT OF IN COLLABORAZIONE CON/WITH COLLABORATION WITH INTERNATIONAL PARTNERS PROJECT MARKET PARTNERS TIES THAT BIND CON IL SUPPORTO DI/WITH THE SUPPORT OF CAMPUS CON LA PARTECIPAZIONE DI/WITH THE PARTICIPATION OF MAIN SPONSORS OFFICIAL SPONSORS FESTIVAL PARTNERS TECHNICAL PARTNERS ® MAIN MEDIA PARTNERS MEDIA PARTNERS CON / WITH FOCUS ASIA April 30/May 2, 2019 – Udine After the big success of the last edition, the Far East Film Festival is thrilled to welcome to Udine more than 200 international industry professionals taking part in FOCUS ASIA 2019! This year again, the programme will include a large number of events meant to foster professional and artistic exchanges between Asia and Europe. The All Genres Project Market will present 15 exciting projects in development coming from 10 different countries. The final line up will feature a large variety of genres and a great diversity of profiles of directors and producers, proving one of the main goals of the platform: to explore both the present and future generation of filmmakers from both continents. For the first time the market will include a Chinese focus, exposing 6 titles coming from China, Hong Kong and Taiwan. Thanks to the partnership with Trieste Science+Fiction Festival and European Film Promotion, Focus Asia 2019 will host the section Get Ready for Cannes offering to 12 international sales agents the chance to introduce their most recent line up to more than 40 buyers from Asia, Europe and North America. -

ARBOR, FRIDAY, APRIL 18, 1862. Tsto. 848

Hardy Eveareer.s. In all cities, villages and to some ex- tent in the country, it is becoming quite PL'BI.TSilKP EVERY KKIIMY .MUHMNC, in th« Third fashionable to plant different kinds of S orv if £tlM iii-ick l~> a •.. • I " r aM HflMB and Huron S weta trees for the purpose of ornameut; and in a few cases for protection from tho cold winds This " fashion" is very laud, Entrance <»n Hare* SI reet, opposite the Franklin. able, nnd there is no danger of its ever becoming too prevalent; indued, it isasu. EL1HU 13. [POJNTJD a:iy ' more honored in the breach thau KdiLor and. 1'ublisrier. in tho observance.' No man was ever I'E.'IMS, «.l,5O A VEiB IK ADVANCE. heard to say that ho had set out too many shade trees, or that ho was sorrv ADVERTISING-. "Vol. ARBOR, FRIDAY, APRIL 18, 1862. TSTo. 848. for the time .spent or the money outlay One square (12 Une« or less": unc greek, M)o©Bt»; ana1 in thu endeavor to make his home moru 15 oenis for«vcvy insertion tin.it-;iiler, less than three n——•— comfortable or beautiful. Many persons ^ months... -S3 Quarter col. 1 year $20 From Si H:S h r the Littlu Ones >t Hi>mc. t Of Fed, a« it he had not seen a com Her father heard her Bobbing a Postal Incident. The Peninsula Between the York and Brilliant Exploit of Col. Geary. arc deterred from putting out evegreens, >ue do 6 do Hfilfcornin G mos 18 Jamea Rivers llali do 1 year 35 The Snowdrop. -

CHIFFRES ET NOMBRES GDES PTES LGS 11 Réalisateurs

CHIFFRES ET NOMBRES GDES PTES LGS 11 réalisateurs September 11 u 2 3 ABADI Sou Cherchez la femme 2 2 ABBASS Hiam Héritage (Inheritance) 2 3 ABEL Dominique Rumba 2 ABEL Dominique Fée (La) 1 ABOUET Marguerite Aya de Yopougon 1 2 ABRAHAMSON Lenny Garage 1 ABRAHAMSON Lenny Room 3 3 ABRAMS Jeffrey-Jacob Star Trek: into darkness 3D 3 2 ABRAMS Jeffrey-Jacob Super 8 3 ABU-ASSAD Hany Montagne entre nous (La) (The 3 Mountain Between Us) A DONNER ABU-ASSAD Hany Omar 2 2 ABU-ASSAD Hany Paradise now 2 2 ACEVEDO César Terre et l'ombre (La) (La Tierra y la 2 Sombra) ACHACHE Mona Hérisson (Le) 3 1 ACKERMAN Chantal Nuit et jour 3 2 ADABACHYAN Aleksandr Mado, poste restante 1 3 ADE Maren Toni Erdmann 3 2 ADLON Percy Zuckerbaby 1 3 AFFLECK Ben Argo 2 3 AFFLECK Ben Town (The) 3 3 AGHION Gabriel Absolument fabuleux 2 moy AGHION Gabriel Pédale dure 1 2 AGOU Christophe Sans adieu 1 1 AGOU Christophe Sans adieu 1 1 AGÜERO Pablo Eva ne dort pas (Eva no duerme) 2 AIELLO Shu Paese de Calabria (Un) 2 AJA Alexandre Mirrors 2 AJA Alexandre Piranha – 3D 3 3 AKERMAN Chantal Captive 3 3 AKERMAN Chantal Divan à New York (Un) 2 2 AKHAVAN Desiree Come as you are (The Miseducation of 2 2 Cameron Post) AKIN Fatih In the fade 2 1 AKIN Fatih Soul kitchen (Soul kitchen) 1 AKIN Fatih Cut (The) (La Blessure) 2 AKIN Fatih New York, I love you 2 2 AKIN Fatih Polluting paradise 1 3 AKOLKAR Dheeraj Liv et Ingmar (Liv & Ingmar) 2 2 ALBERDI Maite Ecole de la vie (L') (The Grown-Ups) 1 ALBERTINI Dario Figlio Manuel (Il) 1 1 ALCALA José Coup d'éclat 2 1 ALDRICH Robert En quatrième vitesse -

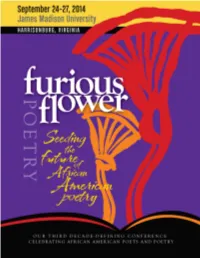

Furiousflower2014 Program.Pdf

Dedication “We are each other’s harvest; we are each other’s business; we are each other’s magnitude and bond.” • GWENDOLYN BROOKS Dedicated to the memory of these poets whose spirit lives on: Ai Margaret Walker Alexander Maya Angelou Alvin Aubert Amiri Baraka Gwendolyn Brooks Lucille Clifton Wanda Coleman Jayne Cortez June Jordan Raymond Patterson Lorenzo Thomas Sherley Anne Williams And to Rita Dove, who has sharpened love in the service of myth. “Fact is, the invention of women under siege has been to sharpen love in the service of myth. If you can’t be free, be a mystery.” • RITA DOVE Program design by RobertMottDesigns.com GALLERY OPENING AND RECEPTION • DUKE HALL Events & Exhibits Special Time collapses as Nigerian artist Wole Lagunju merges images from the Victorian era with Yoruba Gelede to create intriguing paintings, and pop culture becomes bedfellows with archetypal imagery in his kaleidoscopic works. Such genre bending speaks to the notions of identity, gender, power, and difference. It also generates conversations about multicultur- alism, globalization, and transcultural ethos. Meet the artist and view the work during the Furious Flower reception at the Duke Hall Gallery on Wednesday, September 24 at 6 p.m. The exhibit is ongoing throughout the conference, 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. FUSION: POETRY VOICED IN CHORAL SONG FORBES CENTER FOR THE PERFORMING ARTS Our opening night concert features solos by soprano Aurelia Williams and performances by the choirs of Morgan State University (Eric Conway, director) and James Madison University (Jo-Anne van der Vat-Chromy, director). In it, composer and pianist Randy Klein presents his original music based on the poetry of Margaret Walker, Michael Harper, and Yusef Komunyakaa. -

Cassette Books, CMLS,P.O

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 319 210 EC 230 900 TITLE Cassette ,looks. INSTITUTION Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. National Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped. PUB DATE 8E) NOTE 422p. AVAILABLE FROMCassette Books, CMLS,P.O. Box 9150, M(tabourne, FL 32902-9150. PUB TYPE Reference Materials Directories/Catalogs (132) --- Reference Materials Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC17 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Adults; *Audiotape Recordings; *Blindness; Books; *Physical Disabilities; Secondary Education; *Talking Books ABSTRACT This catalog lists cassette books produced by the National Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped during 1989. Books are listed alphabetically within subject categories ander nonfiction and fiction headings. Nonfiction categories include: animals and wildlife, the arts, bestsellers, biography, blindness and physical handicaps, business andeconomics, career and job training, communication arts, consumerism, cooking and food, crime, diet and nutrition, education, government and politics, hobbies, humor, journalism and the media, literature, marriage and family, medicine and health, music, occult, philosophy, poetry, psychology, religion and inspiration, science and technology, social science, space, sports and recreation, stage and screen, traveland adventure, United States history, war, the West, women, and world history. Fiction categories includer adventure, bestsellers, classics, contemporary fiction, detective and mystery, espionage, family, fantasy, gothic, historical fiction, -

Game Developer Index 2019

Game Developer Index 2019 Second edition October 2019 Published by the Swedish Games Industry Research: Nayomi Arvell Layout: Kim Persson Illustration, cover: Pontus Ullbors Text & analysis: Johanna Nylander The Swedish Games Industry is a collaboration between trade organizations ANGI and Spelplan-ASGD. ANGI represents publishers and distributors and Spelplan-ASGD represents developers and producers. Dataspelsbranschen Swedish Games Industry Magnus Ladulåsgatan 3, SE-116 35 Stockholm www.swedishgamesindustry.com Contact: [email protected] Key Figures KEY FIGURES 2018 2017 2016 2015 2014 2013 Number of companies 384 (+12%) 343 (+22%) 282 (+19%) 236 (+11%) 213 (25+%) 170 (+17%) Revenue EUR M 1 872 (+33%) 1 403 (+6%) 1 325 (+6%) 1 248 (+21%) 1 028 (+36%) 757 (+77%) Profit EUR M 335 (-25%) 446 (-49%) 872 (+65%) 525 (+43%) 369 (29+%) 287 (+639%) Employees 7 924 (+48%) 5 338 (+24%) 4 291 (+16%) 3 709 (+19%) 3 117 (+23%) 2 534 (+29%) Employees based in 5 320 (+14%) 4 670 (+25%) 3 750 No data No data No data Sweden Men 6 224 (79%) 4 297 (80%) 3 491 (81%) 3 060 (82%) 2 601 (83%) 2 128 (84%) Women 1 699 (21%) 1 041 (20%) 800 (19%) 651 (18%) 516 (17%) 405 (16%) Tom Clancy’s The Division 2, Ubisoft Massive Entertainment Index Preface Art and social impact – the next level for Swedish digital games 4 Preface 6 Summary The game developers just keep breaking records. What once was a sensation making news headlines 8 Revenue – “Swedish video games succeed internationally” 9 Revenue & Profit – is now the established order and every year new records are expected from the Game Developer 12 Employees Index.