Prosthetic Intimacies: Television, Performance Studies, and the Makings of (A) Life

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Feminism, Postfeminism, Liz Lemonism: Comedy and Gender Politics on 30 Rock

Genders 1998-2013 Genders 1998-2013 Genders 1998-2013 Home (/gendersarchive1998-2013/) Feminism, Postfeminism, Liz Lemonism: Comedy and Gender Politics on 30 Rock Feminism, Postfeminism, Liz Lemonism: Comedy and Gender Politics on 30 Rock May 1, 2012 • By Linda Mizejewski (/gendersarchive1998-2013/linda-mizejewski) [1] The title of Tina Fey's humorous 2011 memoir, Bossypants, suggests how closely Fey is identified with her Emmy-award winning NBC sitcom 30 Rock (2006-), where she is the "boss"—the show's creator, star, head writer, and executive producer. Fey's reputation as a feminist—indeed, as Hollywood's Token Feminist, as some journalists have wryly pointed out—heavily inflects the character she plays, the "bossy" Liz Lemon, whose idealistic feminism is a mainstay of her characterization and of the show's comedy. Fey's comedy has always focused on gender, beginning with her work on Saturday Night Live (SNL) where she became that show's first female head writer in 1999. A year later she moved from behind the scenes to appear in the "Weekend Update" sketches, attracting national attention as a gifted comic with a penchant for zeroing in on women's issues. Fey's connection to feminist politics escalated when she returned to SNL for guest appearances during the presidential campaign of 2008, first in a sketch protesting the sexist media treatment of Hillary Clinton, and more forcefully, in her stunning imitations of vice-presidential candidate Sarah Palin, which launched Fey into national politics and prominence. [2] On 30 Rock, Liz Lemon is the head writer of an NBC comedy much likeSNL, and she is identified as a "third wave feminist" on the pilot episode. -

Echoes of Memory Volume 9

Echoes of Memory Volume 9 CONTENTS JACQUELINE MENDELS BIRN MICHEL MARGOSIS The Violins of Hope ...................................................2 In Transit, Spain ........................................................ 28 RUTH COHEN HARRY MARKOWICZ Life Is Good ....................................................................3 A Letter to the Late Mademoiselle Jeanne ..... 34 Sunday Lunch at Charlotte’s House ................... 36 GIDEON FRIEDER True Faith........................................................................5 ALFRED MÜNZER Days of Remembrance in Rymanow ..................40 ALBERT GARIH Reunion in Ebensee ................................................. 43 Flory ..................................................................................8 My Mother ..................................................................... 9 HALINA YASHAROFF PEABODY Lying ..............................................................................46 PETER GOROG A Gravestone for Those Who Have None .........12 ALFRED TRAUM A Three-Year-Old Saves His Mother ..................14 The S.S. Zion ...............................................................49 The Death Certificate That Saved Vienna, Chanukah 1938 ...........................................52 Our Lives ..................................................................................... 16 SUSAN WARSINGER JULIE KEEFER Bringing the Lessons Home ................................. 54 Did He Know I Was Jewish? ...................................18 Feeling Good ...............................................................55 -

30 Rock: Complexity, Metareferentiality and the Contemporary Quality Sitcom

30 Rock: Complexity, Metareferentiality and the Contemporary Quality Sitcom Katrin Horn When the sitcom 30 Rock first aired in 2006 on NBC, the odds were against a renewal for a second season. Not only was it pitched against another new show with the same “behind the scenes”-idea, namely the drama series Studio 60 on the Sunset Strip. 30 Rock’s often absurd storylines, obscure references, quick- witted dialogues, and fast-paced punch lines furthermore did not make for easy consumption, and thus the show failed to attract a sizeable amount of viewers. While Studio 60 on the Sunset Strip did not become an instant success either, it still did comparatively well in the Nielson ratings and had the additional advantage of being a drama series produced by a household name, Aaron Sorkin1 of The West Wing (NBC, 1999-2006) fame, at a time when high-quality prime-time drama shows were dominating fan and critical debates about TV. Still, in a rather surprising programming decision NBC cancelled the drama series, renewed the comedy instead and later incorporated 30 Rock into its Thursday night line-up2 called “Comedy Night Done Right.”3 Here the show has been aired between other single-camera-comedy shows which, like 30 Rock, 1 | Aaron Sorkin has aEntwurf short cameo in “Plan B” (S5E18), in which he meets Liz Lemon as they both apply for the same writing job: Liz: Do I know you? Aaron: You know my work. Walk with me. I’m Aaron Sorkin. The West Wing, A Few Good Men, The Social Network. -

Emotional and Linguistic Analysis of Dialogue from Animated Comedies: Homer, Hank, Peter and Kenny Speak

Emotional and Linguistic Analysis of Dialogue from Animated Comedies: Homer, Hank, Peter and Kenny Speak. by Rose Ann Ko2inski Thesis presented as a partial requirement in the Master of Arts (M.A.) in Human Development School of Graduate Studies Laurentian University Sudbury, Ontario © Rose Ann Kozinski, 2009 Library and Archives Bibliotheque et 1*1 Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington OttawaONK1A0N4 OttawaONK1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-57666-3 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-57666-3 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, prefer, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la these ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Junior Mints and Their Bigger Than Bite-Size Role in Complicating Product Placement Assumptions

Salve Regina University Digital Commons @ Salve Regina Pell Scholars and Senior Theses Salve's Dissertations and Theses 5-2010 Junior Mints and Their Bigger Than Bite-Size Role in Complicating Product Placement Assumptions Stephanie Savage Salve Regina University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.salve.edu/pell_theses Part of the Advertising and Promotion Management Commons, and the Marketing Commons Savage, Stephanie, "Junior Mints and Their Bigger Than Bite-Size Role in Complicating Product Placement Assumptions" (2010). Pell Scholars and Senior Theses. 54. https://digitalcommons.salve.edu/pell_theses/54 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Salve's Dissertations and Theses at Digital Commons @ Salve Regina. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pell Scholars and Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Salve Regina. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Savage 1 “Who’s gonna turn down a Junior Mint? It’s chocolate, it’s peppermint ─it’s delicious!” While this may sound like your typical television commercial, you can thank Jerry Seinfeld and his butter fingers for what is actually one of the most renowned lines in television history. As part of a 1993 episode of Seinfeld , subsequently known as “The Junior Mint,” these infamous words have certainly gained a bit more attention than the show’s writers had originally bargained for. In fact, those of you who were annoyed by last year’s focus on a McDonald’s McFlurry on NBC’s 30 Rock may want to take up your beef with Seinfeld’s producers for supposedly showing marketers the way to the future ("Brand Practice: Product Integration Is as Old as Hollywood Itself"). -

Snowschool Offered to Local Students Environment

6 TUESDAY, JANUARY 28, 2020 The Inyo Register SnowSchool offered to local students environment. The second with water. The food color- journey is unique. This Bishop, session allows students to ing and glitter represent game shows students how Mammoth review the first lesson and different, pollutants that water moves through the learn how to calculate snow might enter the watershed, earth, oceans, and atmo- Lakes fifth- water equivalent. The final and students can observe sphere, and gives them a grade students session takes students how the pollutants move better understanding of from the classroom to the and collect in different the water cycle. participate in mountains for a SnowSchool bodies of water. For the final in-class field day. Once firmly in For the second in-class activity, students learn SnowSchool snowshoes, the students activity, students focus on about winter ecology and learn about snow science the water cycle by taking how animals adapt for the By John Kelly hands-on and get a chance on the role of a water mol- winter. Using Play-Doh, Education Manager, ESIA to play in the snow. ecule and experiencing its they create fictional ani- During the in-class ses- journey firsthand. Students mals that have their own For the last five years, sion, students participate break up into different sta- winter adaptations. Some the Eastern Sierra in three activities relating tions. Each station repre- creations in past Interpretive Association to watersheds, the water sents a destination a water SnowSchools had skis for (ESIA) and Friends of the cycle, and winter ecology. molecule might end up, feet to move more easily Inyo have provided instruc- In the first activity, stu- such as a lake, river, cloud, on the snow and shovels tors who deliver the Winter dents create their own glacier, ocean, in the for hands for better bur- Wildlands Alliance’s watershed, using tables groundwater, on the soil rowing ability. -

Die Flexible Welt Der Simpsons

BACHELORARBEIT Herr Benjamin Lehmann Die flexible Welt der Simpsons 2012 Fakultät: Medien BACHELORARBEIT Die flexible Welt der Simpsons Autor: Herr Benjamin Lehmann Studiengang: Film und Fernsehen Seminargruppe: FF08w2-B Erstprüfer: Professor Peter Gottschalk Zweitprüfer: Christian Maintz (M.A.) Einreichung: Mittweida, 06.01.2012 Faculty of Media BACHELOR THESIS The flexible world of the Simpsons author: Mr. Benjamin Lehmann course of studies: Film und Fernsehen seminar group: FF08w2-B first examiner: Professor Peter Gottschalk second examiner: Christian Maintz (M.A.) submission: Mittweida, 6th January 2012 Bibliografische Angaben Lehmann, Benjamin: Die flexible Welt der Simpsons The flexible world of the Simpsons 103 Seiten, Hochschule Mittweida, University of Applied Sciences, Fakultät Medien, Bachelorarbeit, 2012 Abstract Die Simpsons sorgen seit mehr als 20 Jahren für subversive Unterhaltung im Zeichentrickformat. Die Serie verbindet realistische Themen mit dem abnormen Witz von Cartoons. Diese Flexibilität ist ein bestimmendes Element in Springfield und erstreckt sich über verschiedene Bereiche der Serie. Die flexible Welt der Simpsons wird in dieser Arbeit unter Berücksichtigung der Auswirkungen auf den Wiedersehenswert der Serie untersucht. 5 Inhaltsverzeichnis Inhaltsverzeichnis ............................................................................................. 5 Abkürzungsverzeichnis .................................................................................... 7 1 Einleitung ................................................................................................... -

73Rd-Nominations-Facts-V2.Pdf

FACTS & FIGURES FOR 2021 NOMINATIONS as of July 13 does not includes producer nominations 73rd EMMY AWARDS updated 07.13.2021 version 1 Page 1 of 20 SUMMARY OF MULTIPLE EMMY WINS IN 2020 Watchman - 11 Schitt’s Creek - 9 Succession - 7 The Mandalorian - 7 RuPaul’s Drag Race - 6 Saturday Night Live - 6 Last Week Tonight With John Oliver - 4 The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel - 4 Apollo 11 - 3 Cheer - 3 Dave Chappelle: Sticks & Stones - 3 Euphoria - 3 Genndy Tartakovsky’s Primal - 3 #FreeRayshawn - 2 Hollywood - 2 Live In Front Of A Studio Audience: “All In The Family” And “Good Times” - 2 The Cave - 2 The Crown - 2 The Oscars - 2 PARTIAL LIST OF 2020 WINNERS PROGRAMS: Comedy Series: Schitt’s Creek Drama Series: Succession Limited Series: Watchman Television Movie: Bad Education Reality-Competition Program: RuPaul’s Drag Race Variety Series (Talk): Last Week Tonight With John Oliver Variety Series (Sketch): Saturday Night Live PERFORMERS: Comedy Series: Lead Actress: Catherine O’Hara (Schitt’s Creek) Lead Actor: Eugene Levy (Schitt’s Creek) Supporting Actress: Annie Murphy (Schitt’s Creek) Supporting Actor: Daniel Levy (Schitt’s Creek) Drama Series: Lead Actress: Zendaya (Euphoria) Lead Actor: Jeremy Strong (Succession) Supporting Actress: Julia Garner (Ozark) Supporting Actor: Billy Crudup (The Morning Show) Limited Series/Movie: Lead Actress: Regina King (Watchman) Lead Actor: Mark Ruffalo (I Know This Much Is True) Supporting Actress: Uzo Aduba (Mrs. America) Supporting Actor: Yahya Abdul-Mateen II (Watchmen) updated 07.13.2021 version 1 Page -

2010 16Th Annual SAG AWARDS

CATEGORIA CINEMA Melhor ator JEFF BRIDGES / Bad Blake - "CRAZY HEART" (Fox Searchlight Pictures) GEORGE CLOONEY / Ryan Bingham - "UP IN THE AIR" (Paramount Pictures) COLIN FIRTH / George Falconer - "A SINGLE MAN" (The Weinstein Company) MORGAN FREEMAN / Nelson Mandela - "INVICTUS" (Warner Bros. Pictures) JEREMY RENNER / Staff Sgt. William James - "THE HURT LOCKER" (Summit Entertainment) Melhor atriz SANDRA BULLOCK / Leigh Anne Tuohy - "THE BLIND SIDE" (Warner Bros. Pictures) HELEN MIRREN / Sofya - "THE LAST STATION" (Sony Pictures Classics) CAREY MULLIGAN / Jenny - "AN EDUCATION" (Sony Pictures Classics) GABOUREY SIDIBE / Precious - "PRECIOUS: BASED ON THE NOVEL ‘PUSH’ BY SAPPHIRE" (Lionsgate) MERYL STREEP / Julia Child - "JULIE & JULIA" (Columbia Pictures) Melhor ator coadjuvante MATT DAMON / Francois Pienaar - "INVICTUS" (Warner Bros. Pictures) WOODY HARRELSON / Captain Tony Stone - "THE MESSENGER" (Oscilloscope Laboratories) CHRISTOPHER PLUMMER / Tolstoy - "THE LAST STATION" (Sony Pictures Classics) STANLEY TUCCI / George Harvey – “UM OLHAR NO PARAÍSO” ("THE LOVELY BONES") (Paramount Pictures) CHRISTOPH WALTZ / Col. Hans Landa – “BASTARDOS INGLÓRIOS” ("INGLOURIOUS BASTERDS") (The Weinstein Company/Universal Pictures) Melhor atriz coadjuvante PENÉLOPE CRUZ / Carla - "NINE" (The Weinstein Company) VERA FARMIGA / Alex Goran - "UP IN THE AIR" (Paramount Pictures) ANNA KENDRICK / Natalie Keener - "UP IN THE AIR" (Paramount Pictures) DIANE KRUGER / Bridget Von Hammersmark – “BASTARDOS INGLÓRIOS” ("INGLOURIOUS BASTERDS") (The Weinstein Company/Universal Pictures) MO’NIQUE / Mary - "PRECIOUS: BASED ON THE NOVEL ‘PUSH’ BY SAPPHIRE" (Lionsgate) Melhor elenco AN EDUCATION (Sony Pictures Classics) DOMINIC COOPER / Danny ALFRED MOLINA / Jack CAREY MULLIGAN / Jenny ROSAMUND PIKE / Helen PETER SARSGAARD / David EMMA THOMPSON / Headmistress OLIVIA WILLIAMS / Miss Stubbs THE HURT LOCKER (Summit Entertainment) CHRISTIAN CAMARGO / Col. John Cambridge BRIAN GERAGHTY / Specialist Owen Eldridge EVANGELINE LILLY / Connie James ANTHONY MACKIE / Sgt. -

Bossypants? One, Because the Name Two and a Half Men Was Already Taken

Acknowledgments I would like to gratefully thank: Kay Cannon, Richard Dean, Eric Gurian, John Riggi, and Tracy Wigfield for their eyes and ears. Dave Miner for making me do this. Reagan Arthur for teaching me how to do this. Katie Miervaldis for her dedicated service and Latvian demeanor. Tom Ceraulo for his mad computer skills. Michael Donaghy for two years of Sundays. Jeff and Alice Richmond for their constant loving encouragement and their constant loving interruption, respectively. Thank you to Lorne Michaels, Marc Graboff, and NBC for allowing us to reprint material. Contents Front Cover Image Welcome Dedication Introduction Origin Story Growing Up and Liking It All Girls Must Be Everything Delaware County Summer Showtime! That’s Don Fey Climbing Old Rag Mountain Young Men’s Christian Association The Windy City, Full of Meat My Honeymoon, or A Supposedly Fun Thing I’ll Never Do Again Either The Secrets of Mommy’s Beauty Remembrances of Being Very Very Skinny Remembrances of Being a Little Bit Fat A Childhood Dream, Realized Peeing in Jars with Boys I Don’t Care If You Like It Amazing, Gorgeous, Not Like That Dear Internet 30 Rock: An Experiment to Confuse Your Grandparents Sarah, Oprah, and Captain Hook, or How to Succeed by Sort of Looking Like Someone There’s a Drunk Midget in My House A Celebrity’s Guide to Celebrating the Birth of Jesus Juggle This The Mother’s Prayer for Its Daughter What Turning Forty Means to Me What Should I Do with My Last Five Minutes? Acknowledgments Copyright * Or it would be the biggest understatement since Warren Buffett said, “I can pay for dinner tonight.” Or it would be the biggest understatement since Charlie Sheen said, “I’m gonna have fun this weekend.” So, you have options. -

C:\Documents and Settings\Fre...N.Default\Cache\0\11

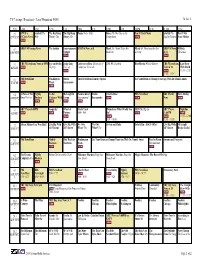

TV Listings Broadcast - Local Broadcast 94501 Fri, Jun. 8 PDT 6 PM 6:30 7 PM 7:30 8 PM 8:30 9 PM 9:30 10 PM 10:30 11 PM 11:30 2.1 KTVU 6 Seinfeld The The Big Bang The Big Bang House Better Half Bones The Hot Dog in the Ten O'Clock News Seinfeld The How I Met KTVUDT O'Clock News Wife Theory The Theory The Competition new English Patient Your Mother new 4.1 KRON 4 Evening News The Insider Entertainment KRON 4 News at 8 Monk Mr. Monk Takes His Monk Mr. Monk and the Red KRON 4 News 30 Rock KRONDT Tonight Medicine Herring at 11 Christmas new new 5.1 CBS 5 Eyewitness News at 6PM Eye on the Bay Judge Judy Undercover Boss University of CSI: NY Crushed Blue Bloods Whistle Blower CBS 5 Eyewitness Late Show KPIXDT new Daytrip: Tires of California, Riverside News at 11 With David new new 11:35 - 12:37 11:00 - 11:35 6.1 PBS NewsHour Washington Studio The Ed Sullivan Comedy Special Use Your Brain to Change Your Age With Dr. Daniel Amen KVIEDT new Week Sacramento new 6.2 A Place of Our Nightly To the McLaughlin Need to Know Studio Charlie Rose PBS NewsHour BBC World Tavis Smiley KVIEDT2 Own Week in Business Contrary With Group International Sacramento new new News new new new new new 7.1 ABC7 News 6:00PM Jeopardy! Wheel of Shark Tank Primetime: What Would You 20/20 The Big Lie ABC7 News Nightline KGODT new new Fortune 8:00 - 9:01 Do? new 11:00PM new new new new 11:35 - 12:00 9:01 - 10:00 11:00 - 11:35 7.2 Alyssa Milano Uses Wen Hair! Live Big With Live Big With We Owe We Owe Steven and Chris Total Gym - $14.95 Offer! Live Big With My Family KGODT2 Ali Vincent Ali Vincent What? The What? The Ali Vincent Recipe Rocks! 9.1 PBS NewsHour Nightly This Week in Washington Use Your Brain to Change Your Age With Dr. -

Los Simpson Versus Trump

LOS SIMPSON VERSUS TRUMP Graciela Martínez-Zalce Sánchez* Para GAH, quien no conocía a los Simpson y cree conocer a Trump And that is how I became a Democrat HOMERO J. SIMPSON El corto titulado “Donald Trump’s first 100 days in office”,1 publicado el 26 de abril de 2017 como parte de la temporada 28 de Los Simpson en el canal Animation Fox en Youtube, cierra con un negro sarcasmo.2 En una serie, en la que por casi tres décadas se han utilizado los matices y las sutilezas indis- pensables para que los episodios, escritos con gran inteligencia por presti- giosos grupos de guionistas irreverentes,3 tengan como característica sobresaliente tres figuras retóricas, la parodia, la ironía y, sobre todo, la sátira, * Directora e investigadora del Centro de Investigaciones sobre América del Norte de la Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, <[email protected]>. 1 En este artículo utilizaré los títulos de los capítulos y los nombres que se le han dado a los per- sonajes en español en el doblaje para México (donde la serie comenzó a transmitirse en el canal 13 de Imevisión en marzo de 1991, los martes a las 20:30 horas), pero, en su mayoría, las citas textuales de los diálogos se harán en el original en inglés debido a que el doblaje tropicaliza las alusiones y, por tratarse aquí de los partidos y los políticos estadunidenses, es importante que se conserven. En el caso específico de este corto, puesto que no fue exhibido fuera de Estados Unidos y Canadá, y como la wiki en español aún está consignando la temporada 27, el título del mismo se anota en inglés.