THE UNIVERSITY of HULL the Music for Rameau's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

14 December 2012 Page 1 of 11 SATURDAY 08 DECEMBER 2012 4:34 AM Favourite Piece of Music to the Rest of the UK

Radio 3 Listings for 8 – 14 December 2012 Page 1 of 11 SATURDAY 08 DECEMBER 2012 4:34 AM favourite piece of music to the rest of the UK. In the run up to Sibelius, Jean (1865-1957) Christmas we'll be hearing about music that reminds listeners of SAT 01:00 Through the Night (b01p2wc3) Serenade No.1 in D major for violin & orchestra (Op.69a) the festive season. Jonathan Swain a recital from the 66th International Chopin Judy Kang (violin), Orchestre Symphonique de Laval, Jean- Festival in Duszniki Zdrój in Poland - Tonight Daniil Trifonov - François Rivest (conductor) winner of the 2011 Tchaikovsky Piano Competition. SAT 09:00 CD Review (b01p3mb1) 4:42 AM Building a Library: Bartok: Concerto for Orchestra 1:01 AM Tárrega, Francisco (1852-1909) Schubert, Franz [1797-1828] Recuerdos de la Alhambra With Andrew McGregor. Including Building a Library: Bartok: 4 Schubert Song transcriptions by Liszt, Franz [1811-1886] Ana Vidović (guitar) Concerto for Orchestra; Chamber music, by Schubert, Mozart, Daniil Trifonov (piano) Messiaen; Disc of the Week: Prokofiev: Violin Concerto No 2. 4:47 AM 1:17 AM Schein, Johann Hermann (1586-1630) Schumann, Robert [1810-1856] No.26 Canzon for 5 instruments in A minor 'Corollarium' - SAT 12:15 Music Matters (b01p3mb3) Widmung (Dedication), from 'Myrten, op. 25/1, (S. 566) from Banchetto Musicale, Leipzig (1617) Jonathan Harvey Tribute, William Christie, Royal Northern Daniil Trifonov (piano) Hesperion XX, Jordi Savall (descant viola da gamba & director) College of Music 1:21 AM 4:51 AM Tom Service pays tribute to composer Jonathan Harvey. Plus Liszt, Franz [1811-1886] Rossini, Gioachino (1792-1868) conductor William Christie and a celebration of 40 years of the La campanella, No. -

Table 7-1 French Opera Repertory 1753–62

1 Table 12-1 French Opera Repertory 1753–63 (with Court performances of opéras- comiques in 1761–63) See Table 1-1 for the period 1742–52. This Table is an overview of commissions and revivals in the elite institutions of French opera. Académie Royale de Musique and Court premieres are listed separately for each work (albeit information is sometimes incomplete). The left-hand column includes both absolute world premieres and important earlier works new to these theatres. Works given across a New Year period are listed twice. Individual entrées are mentioned only when revived separately, or to avoid ambiguity. Prologues are mostly ignored. Sources: BrennerD, KaehlerO, LagraveTP, LajarteO, Lavallière, Mercure, NG, RiceFB, SerreARM. Italian works follow name forms etc. cited in Parisian libretti. LEGEND: ARM = Académie Royale de Musique (Paris Opéra); bal. = ballet; bouf. = bouffon; CI = Comédie-Italienne; cmda = comédie mêlée d’ariettes; com. lyr. = comédie lyrique; d. gioc.= dramma giocoso; div. scen. = divertimento scenico; FB = Fontainebleau; FSG = Foire Saint-Germain; FSL = Foire Saint-Laurent; hér. = héroïque; int. = intermezzo; NG = The New Grove Dictionary of Music; NGO = The New Grove Dictionary of Opera; op. = opéra; p. = pastorale; Vers. = Versailles; < = extract from; R = revised. 1753 ALL AT ARM EXCEPT WHERE MARKED Premieres at ARM (listed first) and Court Revivals at ARM or Court (by original date) Titon & l’Aurore (p. hér., 3: La Marre, Voisenon, Atys (Lully, 1676) FB La Motte / Mondonville, Jan. 9) Phaëton (Lully, 1683) Scaltra governatrice, La (d. gioc., 3: Palomba / Fêtes Grecques et romaines, Les (Blamont, 1723) Cocchi, Jan. 25) Danse, La (<Fêtes d’Hébé, Les)(Rameau, 1739) FB Jaloux corrigé, Le (op. -

RAMEAU LES BORÉADES Václav Luks MENU

RAMEAU LES BORÉADES Václav Luks MENU Tracklist Distribution L'œuvre Compositeur Artistes Synopsis Textes chantés L'Opéra Royal 1 MENU LES BORÉADES VOLUME 1 69'21 1 Ouverture 2'28 2 Menuet 0'44 3 Allegro 1'32 ACTE I 4 Scène 1 - Alphise et Sémire 3'19 Récits en duo et Airs d'Alphise «Suivez la chasse» Deborah Cachet, Caroline Weynants 5 Scène 2 - Borilée et les Précédents 0'29 Air et Récit de Borilée «La chasse à mes regards» Tomáš Šelc 6 Scène 3 - Calisis et les Précédents 2'08 Récit et Air de Calisis «À descendre en ces lieux» Deborah Cachet, Benedikt Kristjánsson 7 Scène 4 - Troupe travestie en Plaisirs et Grâces 0'35 Air de Calisis «Cette troupe aimable» Caroline Weynants, Benedikt Kristjánsson 8 Air gracieux (Ballet) 1'51 9 Air de Sémire «Si l'hymen a des chaines» – Caroline Weynants 0'40 10 Première Gavotte gracieuse 0'32 11 Deuxième Gavotte (Ballet) 0'46 12 Première Gavotte da capo (Ballet) 0'18 2 13 Air de Calisis «C'est dans cet aimable séjour» – Benedikt Kristjánsson 0'46 14 Rondeau vif (Ballet) – Caroline Weynants 2'23 15 Gavotte vive (Ballet) 0'51 16 Deuxième Gavotte (Ballet) 0'53 17 Ariette pour Alphise ou la Confidente (Sémire) «Un horizon serein» 7'37 Deborah Cachet ou Caroline Weynants 18 Contredanse en Rondeau (Ballet) 1'57 19 L'Ouverture pour Entracte ACTE II 20 Scène 1 - Abaris 2'25 Air d'Abaris «Charmes trop dangereux» Mathias Vidal 21 Scène 2 - Adamas et Abaris 0'31 Récit d'Adamas «J'aperçois ce mortel» Benoît Arnould 22 Air d'Adamas «Lorsque la lumière féconde» – Benoît Arnould 1'08 23 Récit d'Abaris et Adamas «Quelle -

Music List for Lent, Holy Week & Easter 2019

Music List for Lent, Holy Week & Easter 2019 (click on the hyperlinks to listen to the pieces – internet access required) Tuesday, March 5th (Eve of Lent) Friday, March 15th Early Christian music Cristobal Morales (1500-1553) Explanation / history of Gregorian chant Circumdederunt me Gregorian chant short explanation Lamentatio Zain Gregorian chant Regina Caeli Saturday, March 16th Thomas Tallis (1505-1585) Ash Wednesday, March 6th Gregorio Allegri (1582-1652) Miserere Spem in alium With different ornamentations Traditional ornamentation Sunday, March 17th Jacobus Clemens non Papa (1510-56) Thursday, March 7th O Maria Vernans Rosa Orthodox- traditional hymn / song Ego Flos Campi Agni parthene Monday, March 18th Friday, March 8th Giovanni Palestrina (1525-1594) Kassia (810-865) Missa papae Marcelli kyrie Sicut Cervus (Like a Saturday, March 9th Hildegard of Bingen (1098-1179) Tuesday, March 19th Ordo virtutum excerpt Robert Parsons (1530-1570) Kyrie Ave Maria Sunday, March 10th Wednesday, March 20th Guillaume de Machaut (1300-1377) Orlande de Lassus (1532-1594) Messe de notre dame Tristis est anima mea Iustorum animae Monday, March 11th Leonel Power (1375/1385-1445) Anima Thursday, March 21st mea William Byrd (1543-1623) Ave Verum Corpus Tuesday, March 12th Ne irascaris domine John Dunstaple (1380-1453) Mass for 4 voices Kyrie Salve scema sanctitatis Mass for 4 voices Agnus Dei Wednesday, March 13th Friday, March 22nd Josquin Des Prez (1440-1521) Jacob Handl (1550-1591) Ave Maria Pater Noster Qui Habitat- psalm 90 v 1-8 Ecce Quomodo Moritur -

Murder in Aubagne: Lynching, Law, and Justice During the French

This page intentionally left blank Murder in Aubagne Lynching, Law, and Justice during the French Revolution This is a study of factions, lynching, murder, terror, and counterterror during the French Revolution. It examines factionalism in small towns like Aubagne near Marseille, and how this produced the murders and prison massacres of 1795–1798. Another major theme is the conver- gence of lynching from below with official terror from above. Although the Terror may have been designed to solve a national emergency in the spring of 1793, in southern France it permitted one faction to con- tinue a struggle against its enemies, a struggle that had begun earlier over local issues like taxation and governance. This study uses the tech- niques of microhistory to tell the story of the small town of Aubagne. It then extends the scope to places nearby like Marseille, Arles, and Aix-en-Provence. Along the way, it illuminates familiar topics like the activity of clubs and revolutionary tribunals and then explores largely unexamined areas like lynching, the sociology of factions, the emer- gence of theories of violent fraternal democracy, and the nature of the White Terror. D. M. G. Sutherland received his M.A. from the University of Sussex and his Ph.D. from the University of London. He is currently professor of history at the University of Maryland, College Park. He is the author of The Chouans: The Social Origins of Popular Counterrevolution in Upper Brittany, 1770–1796 (1982), France, 1789–1815: Revolution and Counterrevolution (1985), and The French Revolution, 1770– 1815: The Quest for a Civic Order (2003) as well as numerous scholarly articles. -

Oct 12 to 18.Txt

CLASSIC CHOICES PLAYLIST Oct. 12 - 18, 2020 PLAY DATE: Mon, 10/12/2020 6:02 AM Antonio Vivaldi Concerto for violin, 2 flutes, 2 oboes & 6:13 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Symphony No. 27 6:29 AM Arcangelo Corelli Concerto Grosso No. 6 6:44 AM Johann Nepomuk Hummel Gesellschafts Rondo 7:02 AM Michel Richard Delalande Suite No. 12 7:16 AM Muzio Clementi Piano Sonata 7:33 AM Mademoiselle Duval Suite from the Ballet "Les Génies" 7:46 AM Georg (Jiri Antonin) Benda Sinfonia No. 9 8:02 AM Johann David Heinichen Concerto for fl,ob,vln,clo,theorbo,st,bc 8:12 AM Franz Joseph Haydn String Quartet 8:31 AM Joan Valent Quatre Estacions a Mallorca 9:05 AM Ralph Vaughan Williams Symphony No. 3 9:41 AM Robert Schumann Fantasiestucke 9:52 AM Ralph Vaughan Williams Silent Noon 10:00 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart LA CLEMENZA DI TITO: Overture 10:06 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Violin Sonata No. 27 10:24 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Flute & Harp Concerto (mvmt 2) 10:34 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Divertimento No. 1 10:49 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Sonata for 2 pianos 11:01 AM Mark Volker Young Prometheus 11:39 AM Georg Philipp Telemann Paris Quartet No. 2:TWV 43: a 3 12:00 PM Ludwig Van Beethoven Wellington's Victory (Battle Symphony) 12:14 PM Ludwig Van Beethoven Piano Sonata No. 6 12:28 PM Johann Strauss, Jr. Wine, Women & Song 12:40 PM John Ireland Piano Trio No. 2 12:54 PM Michael Kamen CRUSOE: Marooned 1:02 PM Mark O'Connor Trio No. -

Rameau Et L'opéra Comique

2020 HIPPOLYTE ET ARICIE HIPPOLYTE ET ARICIEJEAN-PHILIPPE RAMEAU 11, 14, 15, 18, 21, 22 NOVEMBRE 2020 1 Soutenu par Soutenu par AVEC L'AIMABLE AVEC LE SOUTIEN DE PARTENARIAT MÉDIA Madame Aline Foriel-Destezet, PARTICIPATION DE Grande Donatrice de l’Opéra Comique Spectacle capté les 15 et 18 novembre et diffusé ultérieurement. 2 HIPPOLYTETragédie lyrique en cinq actes de Jean-Philippe ET ARICIE Rameau. Livret de l’abbéer Pellegrin Créée à l’Académie royale de musique (Opéra) le 1 octobre 1733. Version de 1757 (sans prologue) avec restauration d’éléments des versions antérieures (1733 et 1742). Raphaël Pichon Direction musicale - Jeanne Candel Mise en scène -Lionel Gonzalez Dramaturgie et direction d’acteurs - Lisa Navarro DécorsPauline - Kieffer Costumes -César Godefroy Lumières - Yannick Bosc Collaboration aux mouvements - Ronan Khalil * Chef de chant - Valérie Nègre Assistante mise en scène -Margaux Nessi Assistante décorsNathalie - Saulnier Assistante costumes - Reinoud van Mechelen Hippolyte - Elsa Benoit SylvieAricie Brunet-Grupposo - Phèdre - Stéphane Degout Opéra Comique Thésée - Nahuel Di Pierro Production Opéra Royal – Château de Versailles Spectacles Neptune, Pluton -Eugénie Lefebvre Coproduction Diane - Lea Desandre Prêtresse de Diane, Chasseresse, Matelote, BergèreSéraphine - Cotrez © Édition Nicolas Sceaux 2007-2020 Œnone - Edwin Fardini Pygmalion. Tous droits réservés Constantin Goubet* re Tisiphone - Martial Pauliat* e 1 Parque - 3h entracte compris Virgile Ancely * 2 Parque,e Arcas - Durée estimée : 3 ParqueGuillaume - Gutierrez* Mercure - * MembresYves-Noël de Pygmalion Genod Iliana Belkhadra Introduction au spectacle Chantez Hippolyte Prologue - Leena Zinsou Bode-Smith (11, 15, 18 et 22 novembre) / et Aricie et Maîtrise Populaire de(14 l’Opéra et 21 novembre) Comique sont temporairement suspendues en raison de la des conditions sanitaires. -

Site/Non-Site Explores the Relationship Between the Two Genres Which the Master of Aix-En- Provence Cultivated with the Same Passion: Landscapes and Still Lifes

site / non-site CÉZANNE site / non-site Guillermo Solana Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid February 4 – May 18, 2014 Fundación Colección Acknowledgements Thyssen-Bornemisza Board of Trustees President The Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza Hervé Irien José Ignacio Wert Ortega wishes to thank the following people Philipp Kaiser who have contributed decisively with Samuel Keller Vice-President their collaboration to making this Brian Kennedy Baroness Carmen Thyssen-Bornemisza exhibition a reality: Udo Kittelmann Board Members María Alonso Perrine Le Blan HRH the Infanta Doña Pilar de Irina Antonova Ellen Lee Borbón Richard Armstrong Arnold L. Lehman José María Lassalle Ruiz László Baán Christophe Leribault Fernando Benzo Sáinz Mr. and Mrs. Barron U. Kidd Marina Loshak Marta Fernández Currás Graham W. J. Beal Glenn D. Lowry HIRH Archduchess Francesca von Christoph Becker Akiko Mabuchi Habsburg-Lothringen Jean-Yves Marin Miguel Klingenberg Richard Benefield Fred Bidwell Marc Mayer Miguel Satrústegui Gil-Delgado Mary G. Morton Isidre Fainé Casas Daniel Birnbaum Nathalie Bondil Pia Müller-Tamm Rodrigo de Rato y Figaredo Isabella Nilsson María de Corral López-Dóriga Michael Brand Thomas P. Campbell Nils Ohlsen Artistic Director Michael Clarke Eriko Osaka Guillermo Solana Caroline Collier Nicholas Penny Marcus Dekiert Ann Philbin Managing Director Lionel Pissarro Evelio Acevedo Philipp Demandt Jean Edmonson Christine Poullain Secretary Bernard Fibicher Earl A. Powell III Carmen Castañón Jiménez Gerhard Finckh HSH Prince Albert II of Monaco Giancarlo Forestieri William Robinson Honorary Director Marsha Rojas Tomàs Llorens David Franklin Matthias Frehner Alejandra Rossetti Peter Frei Katy Rothkopf Isabel García-Comas Klaus Albrecht Schröder María García Yelo Dieter Schwarz Léonard Gianadda Sir Nicholas Serota Karin van Gilst Esperanza Sobrino Belén Giráldez Nancy Spector Claudine Godts Maija Tanninen-Mattila Ann Goldstein Baroness Thyssen-Bornemisza Michael Govan Charles L. -

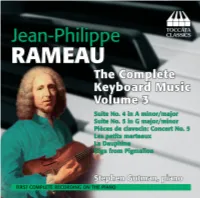

Toccata Classics TOCC0052 Notes

RAMEAU ON THE PIANO, VOLUME THREE 1 by Graham Sadler The two suites recorded on this disc are from the Nouvelles suites de pièces de clavecin of 1729 or 1730, Rameau’s final collection of solo keyboard music.2 Like those of his Pièces de clavessin (1724), they are contrasted both in tonality and character. The Suite in A minor and major is dominated by dances and includes only three character pieces, whereas the Suite in G major and minor consists almost exclusively of pieces with character titles. In its make-up if not its style, the latter thus follows the example of François Couperin, whose first three books of pièces de clavecin (1713, 1717 and 1722) had established the vogue for descriptive pieces. In that sense, Rameau may be regarded as somewhat conservative in devoting half of his two mature solo collections to suites of the more traditional type. Suite No. 4 in A minor and major Conservative they may be, but the dance movements of the Nouvelles suites are among the most highly P developed in the repertory, the first two particularly so. The Allemande 1 unfolds with an effortless grace, its unerring sense of direction reinforced by the many sequential passages. At the end of both sections, the duple semiquaver motion gives way unexpectedly to triplet motion, providing a memorable ‘rhyme’ to the two parts of the movement. The Courante 2, more than twice as long as its predecessors in Rameau’s output, displays a technical sophistication without parallel in the clavecin repertory. Three themes interlock in mainly three- part counterpoint – a bold motif in rising fourths, and two accompanying figures in continuous quavers, the one in sinuous stepwise movement, the other comprising cascading arpeggios. -

Le Monde Galant

The Juilliard School presents Le Monde Galant Juilliard415 Nicholas McGegan, Director Recorded on May 1, 2021 | Peter Jay Sharp Theater FRANCE ANDRÉ CAMPRA Ouverture from L’Europe Galante (1660–1744) SOUTHERN EUROPE: ITALY AND SPAIN JEAN-MARIE LECLAIR Forlane from Scylla et Glaucus (1697–1764) Sicilienne from Scylla et Glaucus CHRISTOPH WILLIBALD GLUCK Menuet from Don Juan (1714–87) MICHEL RICHARD DE LALANDE Chaconne légère des Maures from Les Folies (1657–1726) de Cardenio CHARLES AVISON Con Furia from Concerto No. 6 in D Major, (1709-70) after Domenico Scarlatti CELTIC LANDS: SCOTLAND AND IRELAND GEORG PHILIPP TELEMANN L’Eccossoise from Overture in D Major, TWV55:D19 (1681–1767) NATHANIEL GOW Largo’s Fairy Dance: The Fairies Advancing and (1763–1831) Fairies Dance Cullen O’Neil, Solo Cello TELEMANN L’Irlandoise from Overture in D Minor, TVW55:d2 EASTERN EUROPE: POLAND, BOHEMIA, AND HUNGARY ARR. TELEMANN Danse de Polonie No. 4, TWV45 Polonaise from Concerto Polonois, TWV43:G7 Danse de Polonie No. 1, TWV45 La Hanaquoise, TWV55:D3 TRADITIONAL Three 18th-century Hanák folk tunes RUSSIA TELEMANN Les Moscovites from Overture in B-flat Major, TWV55:B5 Program continues 1 EUROPE DREAMS OF THE EAST: THE OTTOMAN EMPIRE TELEMANN Les Janissaries from Overture in D Major, TWV55:D17 Mezzetin en turc from Overture-Burlesque in B-flat Major, TWV55:B8 PERSIA AND CHINA JEAN-PHILIPPE RAMEAU Air pour Borée from Les Indes galantes (1683–1764) Premier Air pour Zéphire from Les Indes galantes Seconde Air pour Zéphire from Les Indes galantes Entrée des Chinois -

On Art and Artists

A/ 'PI CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY FINE ARTS LIBRARY Cornell University Library N 7445.N82 1907 On art and artists, 3 1924 020 584 946 DATE DUE PRINTEDINU.S./I Cornell University Library The original of tiiis book is in tine Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924020584946 ON ART AND ARTISTS Photo : Elhott and Fry. On A H and A rtisls. ON ART AND ARTISTS BY MAX NORDAU AUTHOR OF " DEGBNBRATION " TRANSLATED BY W. F. HARVEY, M.A. PHILADELPHIA GEORGE W. JACOBS & CO. PUBUSHERS 11 n Printed in Great Britain. CONTENTS CHAF. PACE I. The Social Mission of Art. i II. Socialistic Art—Constantin Meunier . 30 in. The Question of Style .... 44 IV. The Old French Masters . .56 V. A Century of French Art .... 70 VI. The School of 1830 ..... 96 VII. The Triumph of a Revolution— The Realists . .107 Alfred Sisley ..... 123 Camille Pissarro . .133 Whistler's Psychology . .145 VIII. Gustave Moreau ..... 155 " IX. EUGilNE CARRlfeRE . l66 X. Puvis DE Chavannes ..... i8s XL Bright and Dark Painting—Charles Cottet . 201 XII. Physiognomies in Painting . .217 XIII. Augusts Rodin ..... 275 XIV. Resurrection—BARTHOLOMi . 294 XV. Jean CarriSis ...... 308 XVI. Works of Art and Art Criticisms . 320 XVII. Mt Own Opinion ..... 336 Index ....... 349 : ON ART AND ARTISTS I THE SOCIAL MISSION OF ART There exists a school of aestheticism which laughs contemptuously at the mere sight of this superscrip- tion. Art having a mission ! What utter nonsense. A person must be a rank Philistine to connect with the idea of art the conception of a non- artistic mission, be it social or otherwise. -

Judith Van Wanroij • Robert Getchell Juan Sancho • Lisandro Abadie Capriccio Stravagante Les 24 Violons Collegium Vocale G

RAMEAU’S FUNERAL Paris 27. IX. 1764 Jean Gilles • Messe des Morts Judith van Wanroij • Robert Getchell Juan Sancho • Lisandro Abadie Capriccio Stravagante Les 24 Violons Collegium Vocale Gent Skip Sempé RAMEAU’S FUNERAL 4 Graduel I 3’37 Le Service Funèbre de Rameau 5 Graduel II 5’06 Robert Getchell, haute-contre Paris 27. IX. 1764 6 Offertoire 8’29 Judith van Wanroij, dessus 7 Sanctus 1’59 Robert Getchell, haute-contre 8 Hommage à Rameau Juan Sancho, taille Tristes apprêts (Castor et Pollux) 3’18 Lisandro Abadie, basse Jasu Moisio, hautbois Capriccio Stravagante Les 24 Violons 9 Elévation 8’22 Collegium Vocale Gent Judith van Wanroij, dessus Skip Sempé 10 Benedictus 1’59 11 Agnus Dei 3’53 12 Communion 4’06 Jean Gilles (1668-1705) Messe des Morts 13 Sommeil éternel de Rameau (Paris version, 27. IX. 1764) Rondeau tendre (Dardanus) 2’55 14 Apothéose de Rameau Hommages à Rameau (1683-1764) Air des esprits infernaux (Zoroastre) 2’30 1 Introit 11’38 2 Kyrie 4’05 Total time 63’35 3 Hommage à Rameau Gravement (Dardanus) 1’37 2 3 Capriccio Stravagante Les 24 Violons Collegium Vocale Gent Dessus de violon Sophie Gent, Jacek Kurzydło, Maite Larburu, Louis Créac’h Dessus David Wish, Yannis Roger, Marie Rouquié Griet De Geyter, Katja Kunze Haute-contre de violon Aleksandra Lewandowska, Dominique Verkinderen Tuomo Suni, Joanna Huszcza Gabriel Grosbard, Aira Maria Lehtipuu, Myriam Mahnane Taille de violon Haute-contre Simon Heyerick, Martha Moore Sofia Gvirts, Cécile Pilorger Quinte de violon Alexander Schneider, Bart Uvyn David Glidden, Samantha Montgomery