306189 Merged

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Scandinavian Women's Football Goes Global – a Cross-National Study Of

Scandinavian women’s football goes global – A cross-national study of sport labour migration as challenge and opportunity for Nordic civil society Project relevance Women‟s football stands out as an important subject for sports studies as well as social sciences for various reasons. First of all women‟s football is an important social phenomenon that has seen steady growth in all Nordic countries.1 Historically, the Scandinavian countries have been pioneers for women‟s football, and today Scandinavia forms a centre for women‟s football globally.2 During the last decades an increasing number of female players from various countries have migrated to Scandinavian football clubs. Secondly the novel development of immigration into Scandinavian women‟s football is an intriguing example of the ways in which processes of globalization, professionalization and commercialization provide new challenges and opportunities for the Nordic civil society model of sports. According to this model sports are organised in local clubs, driven by volunteers, and built on ideals such as contributing to social cohesion in society.3 The question is now whether this civil society model is simply disappearing, or there are interesting lessons to be drawn from the ways in which local football clubs enter the global market, combine voluntarism and professionalism, idealism and commercialism and integrate new groups in the clubs? Thirdly, even if migrant players stay only temporarily in Scandinavian women‟s football clubs, their stay can create new challenges with regard to their integration into Nordic civil society. For participants, fans and politicians alike, sport appears to have an important role to play in the success or failure of the integration of migrant groups.4 Unsuccessful integration of foreign players can lead to xenophobic feelings, where the „foreigner‟ is seen as an intruder that pollutes the close social cohesion on a sports team or in a club. -

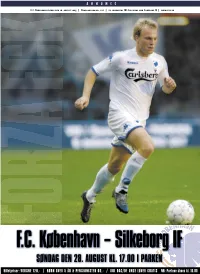

225 FCK-VFF.Indd

ANNONCE F.C. København fredag den 26. august 2005 | Kampprogram nr. 226 | til søndagens SAS Liga kamp mod Silkeborg IF | www.fck.dk K C F A Z R O F Billetpriser: VOKSNE 120,- / BØRN OVER 5 ÅR & PENSIONISTER 60,- / DUL DAG/DE UNGE LØVER GRATIS NB: Portene åbnes kl. 16.00 SØNDAG DEN 28. AUGUST KL. 17.00 I PARKEN F.C. København – Silkeborg IF ANNONCE KØBENHAVN | FREDAG DEN 26. AUGUST 2005 BYENS HOLD Med Silkeborg-kampen afslutter vi, så vidt jeg kan bedømme, indledningen til sæsonen 2005/06, idet der efterfølgende er 14 dages pause i ligaen på grund af landskampe. Som jeg tidligere har pointeret har overbevisning, at point kun kommer Vi har ofte haft problemer med at vi formår at sætte og holde tempo sæsonstarten – ud fra et pointmæs- gennem 90 minutters disciplineret og høste alle tre point mod Silkeborg, i spillet, og at vi er koncentreret og sigt synspunkt – været overordentlig hårdt arbejde. især på udebane, hvorimod vi fokuseret – ikke mindst på mod- tilfredsstillende. Rent faktisk har F.C. har haft et betydeligt bedre tag standerens dødbolde. København aldrig tidligere i klub- Der er i sig selv ingen grund til at klage på midtjyderne her i PARKEN. bens historie fået en bedre start på over, at hold som Viborg og Silkeborg Forhåbentlig kan vi følge op på Under alle omstændigheder får vi ligaen end i indeværende sæson. Fem kommer til PARKEN med et stramt, den statistik, og føje yderligere tre forhåbentlig en seværdig fodbold- sejre og én uafgjort er et absolut til- taktisk koncept, baseret på en massiv meget velkomne point til kontoen. -

Års Beretning 2011

ÅRSBERETNING 2011 ÅRS BERETNING 2011 Udgiver Dansk Boldspil-Union Fodboldens Hus DBU Allé 1 2605 Brøndby Telefon 4326 2222 Telefax 4326 2245 e-mail [email protected] www.dbu.dk Redaktion DBU Kommunikation Lars Berendt (ansvarshavende) Jacob Wadland Pia Schou Nielsen Mikkel Minor Petersen Layout/dtp DBU Grafisk Bettina Emcken Lise Fabricius Carl Herup Høgnesen Fotos Anders & Per Kjærbye/Fodboldbilleder.dk m.fl. Redaktion slut 16. februar 2012 Tryk og distribution Kailow Graphic Oplag 2.500 Pris Kr. 60,00 plus kr. 31,00 i forsendelse 320752_Omslag_2011.indd 1 14/02/12 15.10 ÅRSBERETNING 2011 ÅRS BERETNING 2011 Udgiver Dansk Boldspil-Union Fodboldens Hus DBU Allé 1 2605 Brøndby Telefon 4326 2222 Telefax 4326 2245 e-mail [email protected] www.dbu.dk Redaktion DBU Kommunikation Lars Berendt (ansvarshavende) Jacob Wadland Pia Schou Nielsen Mikkel Minor Petersen Layout/dtp DBU Grafisk Bettina Emcken Lise Fabricius Carl Herup Høgnesen Fotos Anders & Per Kjærbye/Fodboldbilleder.dk m.fl. Redaktion slut 16. februar 2012 Tryk og distribution Kailow Graphic Oplag 2.500 Pris Kr. 60,00 plus kr. 31,00 i forsendelse 320752_Omslag_2011.indd 1 14/02/12 15.10 Dansk Boldspil-Union Årsberetning 2011 Indhold Dansk Boldspil-Union U20-landsholdet . 56 Dansk Boldspil-Union 2011 . 4 U19-landsholdet . 57 UEFA U21 EM 2011 Danmark . 8 U18-landsholdet . 58 Nationale relationer . 10 U17-landsholdet . 60 Internationale relationer . 12 U16-landsholdet . 62 Medlemstal . 14 Old Boys-landsholdet . 63 Organisationsplan 2011 . 16 Kvindelandsholdet . 64 Administrationen . 18 U23-kvindelandsholdet . 66 Bestyrelsen og forretningsudvalget . 19 U19-kvindelandsholdet . 67 Udvalg . 20 U17-pigelandsholdet . 68 Repræsentantskabet . 22 U16-pigelandsholdet . -

Årsskrift 2009 200 9 Vejle Boldklub

Årsskrift 2009 VEJLE BOLDKLUB 2009 Vejle BoldkluB ÅRSSkRIFT 2009 56. årgang På gensyn i: Spar Nord Vejle Havneparken 4, tlf. 76 41 41 00 www.sparnord.dk/vejle Den direkte vej mod målet... - en sikker Topscorer! Vestergade 28 B · 7100 Vejle Tlf. 75 72 04 44 · Fax 75 72 16 18 Vejlevej 29 · 7300 Jelling · Tlf 75 87 18 43 www.petrowsky.dk 2 Vejle BoldkluB ÅRSSkRIFT 2009 56. årgang 3 LEVERANDØR TIL VEJLE BOLDKLUB VB Shoppen er fyldt med originale spillebluser · originale shorts/strømper halstørklæder · caps · penalhuse · støvleposer · nøglebånd · drikkedunke huer · svedbånd · VB armbånd - hele tiden nyheder! Vi har klædt VB på i mange år sammen med hummel - fra miniputter over damer til veteraner og divisionsholdet. HC SPORT - VEJLE Torvegade 9 - 7100 Vejle - Tlf. 75 82 15 99 4 Forord VB’s Årsskrift udkom første gang i 1954 Vi håber, at alle medlemmer, forældre, med følgende indledning: sponsorer og alle øvrige interessenter i og omkring klubben vil få glæde af dette flotte En tradition skabes… årsskrift endnu engang. ”de seneste år i Vejle Boldklubs historie har stået i den sportslige fremgangs tegn, Året 2009 blev også et år med væsentlige således som alle i VB og VB`s Venner helst begivenheder i VB`s historie: ser udviklingen forme sig for deres gamle - Sidste kamp på Nordre Stadion blev spillet klub. Men denne side af klubbens udvikling 25. juni. er ikke tilstrækkelig. den skal følges med - VB Parkens etablering blev endelig sat initiativ og fremskridt inden for ledelsen, i gang 29. juni med første spadestik til det være sig bestyrelsen eller udvalgene. -

Værdiansættelse Af Brøndby If

INFORMATION Dato: 06‐05‐2020 Anslag ekskl. forside, referencer, bilag figur & tabelliste: 123.078. Antal normalsider: 54. Vejleder: Jesper Storm. Simon Ersgaard Studie nr.: S108781 Afgangsprojekt HD(R) VÆRDIANSÆTTELSE AF BRØNDBY IF Strategisk‐ og regnskabsanalyse af Brøndby IF Simon Ersgaard HD(R) 06‐05‐2020 Afgangsprojekt Indholdsfortegnelse 1. Indledning ..................................................................................................................................... 4 1.1 Problemfelt ......................................................................................................................... 5 1.2 Problemformulering ........................................................................................................... 5 1.3 Afgrænsning ....................................................................................................................... 6 1.4 Metode og fremgangsmåde .................................................................................................... 7 1.4.1 Projektet ........................................................................................................................... 7 1.4.2 Empiri/Metodevalg – Teori og modeller ........................................................................... 7 1.4.3 Fremgangsmåden ............................................................................................................. 9 1.4.3 Kilder ................................................................................................................................ -

Women's Football, Europe and Professionalization 1971-2011

Women’s Football, Europe and Professionalization 1971-2011 A Project Funded by the UEFA Research Grant Programme Jean Williams Senior Research Fellow International Centre for Sports History and Culture De Montfort University Contents: Women’s Football, Europe and Professionalization 1971- 2011 Contents Page i Abbreviations and Acronyms iii Introduction: Women’s Football and Europe 1 1.1 Post-war Europes 1 1.2 UEFA & European competitions 11 1.3 Conclusion 25 References 27 Chapter Two: Sources and Methods 36 2.1 Perceptions of a Global Game 36 2.2 Methods and Sources 43 References 47 Chapter Three: Micro, Meso, Macro Professionalism 50 3.1 Introduction 50 3.2 Micro Professionalism: Pioneering individuals 53 3.3 Meso Professionalism: Growing Internationalism 64 3.4 Macro Professionalism: Women's Champions League 70 3.5 Conclusion: From Germany 2011 to Canada 2015 81 References 86 i Conclusion 90 4.1 Conclusion 90 References 105 Recommendations 109 Appendix 1 Key Dates of European Union 112 Appendix 2 Key Dates for European football 116 Appendix 3 Summary A-Y by national association 122 Bibliography 158 ii Women’s Football, Europe and Professionalization 1971-2011 Abbreviations and Acronyms AFC Asian Football Confederation AIAW Association for Intercollegiate Athletics for Women ALFA Asian Ladies Football Association CAF Confédération Africaine de Football CFA People’s Republic of China Football Association China ’91 FIFA Women’s World Championship 1991 CONCACAF Confederation of North, Central American and Caribbean Association Football CONMEBOL -

Danish Football Analysis

Danish Football Analysis Prepared by StatsBomb for DivisionsForeningen April 2019 Contents ● Executive Summary ● Introduction ● Data Clarifications ● Goals, xG and Shots ● Passing, Possessions & Dribbling ● Defending ● Formations ● Age Analysis ● Phases ● Conclusions Executive Summary This project uses football event data to compare the Danish Superliga, English Premier League and German Bundesliga over a five season period beginning in 2014-15. While professional football contains many strong similarities across different leagues, it is also clear that distinct differences exist and StatsBomb was able to draw them out by evaluating datasets for each league. ● Open Play: The Danish Superliga has kept pace with the Premier League in terms of goals, shots, and expected goals volumes, yet both leagues sit below the more action packed Bundesliga. There is also a lessened disparity between the top and bottom Danish teams in comparison to the other leagues. ● Set Pieces: Danish teams score more goals from set pieces than their counterparts in the Premier League and Bundesliga. This includes direct free kicks, corners or indirect free kicks and especially throw ins. The last of which they utilise to a notable extent. Weaker teams across all leagues rely heavily on set pieces, however stronger teams in Denmark get more out of them than their English and German peers. ● Passing: All leagues are moving towards a shorter passing, possession focused approach. Yet the Danish Superliga overall remains a more direct competition. Danish teams also use the wide areas more for creating chances. ● Age: The average age of players in the Danish Superliga is younger than the Premier League and, to a lesser extent, the Bundesliga. -

Årsskriftet for 2013

VEJLE BOLDKLUB ÅRSSKRIFT 2013 60. årgang LEVERANDØR TIL HOS OS KAN DU KØBE DEN SIDSTE NYE SPILLETRØJE Sport24 er fyldt med originale spillebluser, shorts, strømper m.m. Gør også en god han- del på SPORT24.DK Bryggen - Søndertorv 2 - 7100 Vejle - Tlf. 3021 3290 Torvegade 9 - 7100 Vejle - Tlf. 3021 3280 2 Forord Kære læser, omkring det at spille fodbold. I årsskriftet vil vi komme omkring de enkelte I år kan Årsskriftet for Vejle Boldklub fejre 60 hold, og gå i dybden med resultater, stil- års jubilæum. En særdeles flot tradition har linger, udvalgte oplevelser, portrætter og med en kæmpe indsats fra mange gode folk meget andet. i og omkring klubben endnu engang fundet vej i trykken og dermed vej til vore trofaste På det administrative og organisatoriske læsere. plan har vi i det meste af 2013 kørt med en Udgave nr. 60, som du sidder med i hæn- firemands bestyrelse. Opgaverne er fordelt derne, er dokumentation for endnu et år, på nogle fælles opgaver og nogle specifikke hvor Vejle Boldklub har vist sig frem på såvel ansvarsområder. En af de helt store opgaver bredde- som elitefodboldscenen. Det er også har været at få defineret og finde beman- en bekræftelse på, at Vejle Boldklub er en ding til en ny struktur. Det arbejde er nu ved traditionsrig og fremtidsorienteret klub. at være tilendebragt, ja faktisk er en del af Det er en stor glæde for anden gang at få lov det allerede implementeret og fungerende. at skrive forordet til et Årsskrift, som i den Økonomien er tilbage på sporet, og vi kan grad er unikt i dagens Fodbold-Danmark. -

Annual Review 2020 Central Business Registration No

Orifarm Group A/S Energivej 15 5260 Odense S Denmark ÆR NEM KET VA Phone +45 63 95 27 00 S Annual Review 2020 Central Business Registration no. 27347282 www.orifarm.com Tryksag 5041 0826 Scandinavian Print Group CONTENTS Letter from the CEO 03 An incredible year The business 04 Orifarm in brief 06 Our business 12 2020 highlights The foundation 14 25th anniversary 15 Ambitious ownership 16 Who we are 18 New ways of working 20 Supporting talents outside Orifarm 21 Donations and charity 22 Integrating sustainability 24 A game-changing acquisition 28 Room for growth Executive Management 30 Orifarm’s Executive Management 32 More bright years ahead of us Company details and key figures 33 Company details 34 Key figures Annual Review 2020 1 Letter from the CEO An incredible year 2020 is a year we will never forget. Whether we • In August, Hans Bøgh-Sørensen took over as focus on the COVID-19 pandemic and its conse- Chairman of the Board of Directors quences worldwide, on Orifarm and our business primarily in Europe, or on each and every one of • In April, Orifarm signed and announced the big- us as individuals, we learned during the year that gest acquisition in the history of the company. things we took for granted when entering 2020 An acquisition from Takeda including more than were suddenly changed or simply not possible 100 products, two production facilities and more anymore. than 600 employees. This acquisition is a major milestone and will be a true game changer for 2020 will always be linked to the COVID-19 virus, Orifarm going forward and it is impossible to do a 2020 review without touching upon the pandemic and its many unfor- We also expect 2021 to be a bright year for Ori- tunate consequences. -

MLS As a Sports Product – the Prominence of the World's Game in the U.S

MLS as a Sports Product – the Prominence of the World’s Game in the U.S. Stephen A. Greyser Kenneth Cortsen Working Paper 21-111 MLS as a Sports Product – the Prominence of the World’s Game in the U.S. Stephen A. Greyser Harvard Business School Kenneth Cortsen University College of Northern Denmark (UCN) Working Paper 21-111 Copyright © 2021 by Stephen A. Greyser and Kenneth Cortsen. Working papers are in draft form. This working paper is distributed for purposes of comment and discussion only. It may not be reproduced without permission of the copyright holder. Copies of working papers are available from the author. Funding for this research was provided in part by Harvard Business School. MLS as a Sports Product – the Prominence of the World’s Game in the U.S. April 8, 2021 Abstract The purpose of this Working Paper is to analyze how soccer at the professional level in the U.S., with Major League Soccer as a focal point, has developed over the span of a quarter of a century. It is worthwhile to examine the growth of MLS from its first game in 1996 to where the league currently stands as a business as it moves past its 25th anniversary. The 1994 World Cup (held in the U.S.) and the subsequent implementation of MLS as a U.S. professional league exerted a major positive influence on soccer participation and fandom in the U.S. Consequently, more importance was placed on soccer in the country’s culture. The research reported here explores the league’s evolution and development through the cohesion existing between its sporting and business development, as well as its performance. -

Merlin's Danish Faxe Kondi Ligaen 2000

www.soccercardindex.com Merlin’s Danish Faxe Kondi Ligaen 2000 checklist AB Akademisk Boldklub FC København Silkeborg INSERTS □1 Jan Bjur □46 Donatas Vencevicius □89 Morten Bruun □2 Nicolai Stokholm □47 Niclas Jensen □90 Lars Brøgger Klub Logo (Club Logos) □ □3 Jan Hoffmann □48 Todi Jónsson □91 Nocko Jokovic A1 AB Akademisk Boldklub □ □4 Lars Bo Larsen □49 Christian Lønstrup □92 Peter Kjær A2 AGF Aarhus □ □5 Jan Michaelsen □50 Kim Madsen □93 Thomas Røll Larsen A3 Brøndby □ □6 Alex Nielsen □51 Michael ‘Mio’ Nielsen □94 Peter Lassen A4 Esbjerg □ □7 Brian Steen Nielsen □52 David Nielsen □95 Henrik ‘Tømrer’ Pedersen A5 FC København □ □8 Allan Olsen □53 Thomas Rytter □96 Thomas Poulsen A6 Herfølge □ □9 Peter Rasmussen □54 Michael Stensgaard □97 Peter Sørensen A7 Lyngby □ □10 Peter Frank □55 Bo Svensson □98 Bora Zivkovic A8 OB Odense Boldklub □ □11 Abdul Sule □56 Thomas Thorninger A9 Silkeborg Vejle □A10 Vejle AGF Aarhus Herfølge □99 Erik Boye □A11 Viborg □12 Anders Bjerre □57 Thomas Høyer □100 Jens Madsen □A12 AAB Aalborg □13 Kenneth Christiansen □58 Lars Jakobsen □101 Kaspar Dalgas □14 Mads Jørgensen □59 John ‘Faxe’ Jensen □102 Calle Facius Faxe Kondi Superstars (Superstars) □15 Ken Martin □60 Kenneth Jensen □103 Jerry Brown □B1 Brian Steen Nielsen □16 Johnny Mølby □61 Kenneth Kastrup □104 Jesper Mikkelsen □B2 Peter Madsen □17 Bo Nielsen □62 Jesper Falck □105 Henrik Risom □B3 Kenneth Jensen □18 Michael Nonbo □63 Steven Lustü □106 Kent Scholz □B4 Søren Andersen □19 Mads Rieper □64 Henrik Lykke □107 Jesper Ljung □B5 Peter Lassen □20 Kenny Thorup -

Governance Relationships in Football Between Management and Labour Roitman - Governance Relationships Marston, C

Building on the two prior CIES governance studies, this is the third FIFA-mandated research analysing governance relationships in football. This book focuses on those Editions CIES between football’s employers (clubs, leagues and even NAs) and its labour force. Based on a sample of forty countries across all six confederations and questionnaires from players’ associations, leagues and national associations, this research surveys and compares the diverse ‘management-labour’ approaches and scenarios in both men and women’s professional football worldwide. GOVERNANCE RELATIONSHIPS The authors place a special focus on players’ associations and highlight the variety of IN FOOTBALL BETWEEN structures found world-wide. The findings here contribute to a better understanding MANAGEMENT AND LABOUR of the systems, models and relationships in place around the globe when it comes to PLAYERS, CLUBS, LEAGUES & NATIONAL ASSOCIATIONS ‘management’ and ‘labour’. This book explores the representation of Kevin Tallec Marston, Camille Boillat & Fernando Roitman players within decision-making structures at club, league and national association level as well as the regulatory contexts and negotiation instruments linking players and management - such as collaborative agreements/MoUs, CBAs, minimum contract requirements and dispute resolution. In addition, this study provides a first ever global exploration of some of the inner workings of players’ associations and an overview of the key issues in professional football from the player’s perspective. The final chapter offers several models and frameworks illustrating the governance relationships between players and management. All three authors work at the International Centre for Sport Studies (CIES). Kevin Tallec Marston earned his PhD in history and works as research fellow and academic projects manager.