Women's Football, Europe and Professionalization 1971-2011

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aston Villa Women Vs Tottenham Hotspur Women Saturday 6Th February 2021 12.30Pm KO

Aston Villa Women vs Tottenham Hotspur Women Saturday 6th February 2021 12.30pm KO FAWSL ASTON VILLA WOMEN V TOTTENHAM HOTSPUR WOMEN EVERY GOAL EVERY CELEBRATION EVERY MOMENT EVERY TEAM FREE FOLLOW THE ACTION LIVE ON faplayer.thefa.com Column Coach’sGood afternoon and welcome to today’s Barclays FA Women’s Super League fixture versus Tottenham Hotspur. Anybody who watched Spurs last Sunday against So for all of our structure and organisation, we Chelsea would have seen a side who, for the first were unfortunately undone by the very basics of quarter of the game, got themselves into some football. really good goal-scoring opportunities against the current champions. The game got away from Like all good teams do, they exploited an area them before the break, and they will have been of improvement needed from ourselves and we disappointed that they didn’t make the most of as a staff will be looking today to see a shift in their chances at 0-0. mentality to do the basics better and continue to do the good things we did well. With that being said, we can’t hide the fact that this Spurs team suffered their first loss in seven We all know the supporters are kicking every ball last week, so this will be a difficult fixture for us to behind their TVs, laptops and smart phones. claim our first three points of the season at home. We just want you to know that we will go above Chelsea are ruthless, and even when they are not and beyond to work harder than we’ve ever at their best, they carry an array of talent and will worked before, and we will give everything to always pose a threat. -

Three Trophies to Conquer

Number 100 08/2010 Three trophies to conquer UEFADirect100E.indd 1 11.08.10 16:45 2 In this issue From the World Cup to EURO 2012 4 From Offi cial Bulletin UEFA Champions League payouts 6 UEFA Europa League gets off to to UEFA·direct a promising start 8 France win European U19 Championship 10 n March 1956, a little less than two years after UEFA Spain win European Women’s U17 Iwas founded, vice-president Gustav Sebes suggested to Championship 12 the Executive Committee that a quarterly UEFA bulletin be May 1956 News from member associations 16 produced in the three UEFA offi cial languages, English, French and German, and circulated to all national member associations. His idea was accepted and, in May 1956, the maiden Cover issue of the Offi cial Bulletin came out. In his message on Under starter’s orders again, both for Europe’s the fi rst page, the UEFA president, Ebbe Schwartz, set out national teams, as the EURO 2012 quali- the publication’s aims as being to ensure “that the national fi ers get under way, and the clubs dreaming of UEFA Champions League or UEFA Europa associations of our continent may be informed of news and League glory this season. problems which occur within our continent.” Photo: UEFA-Woods From May 1956 to December 2001, 177 issues of the Offi cial Bulletin were published. During this time, the maga- zine grew in size, expanded its readership and opened up its pages to contributions from the national associations, March 1976 enabling them to share their news with their fellow UEFA members. -

FOOMI-NET Working Paper No. 1

WILLIAMS, J. (2011), “Women’s Football, Europe and Professionalization 1971-2011: Global Gendered Labor Markets”, foomi-net Working Papers No. 1, http://www.diasbola.com/uk/foomi-source.html FOOMI-NET www.diasbola.com Working Paper No. 1 Author: Jean Williams Title: Women’s Football, Europe and Professionalization 1971-2011: Global Gendered Labour Markets Date: 20.09.2011 Download: http://www.diasbola.com/uk/foomi-source.html Women’s Football, Europe and Professionalization 1971- 2011: Global Gendered Labour Markets Jean Williams Introduction A recently-published survey aimed at Britain's growing number of family historians, had, as its primary aim, to convey 'the range and diversity of women's work spanning the last two centuries - from bumboat women and nail-makers to doctors and civil servants - and to suggest ways of finding our more about what often seems to be a 'hidden history'.i Professional women football players are part of this hidden history. More surprisingly, no athletes were listed among the 300 or so entries, either in a generalist or specific category: perhaps, because of the significance of amateurism as a prevailing ethos in sport until the 1960s. Another newly-released academic survey by Deborah Simonton Women in 1 WILLIAMS, J. (2011), “Women’s Football, Europe and Professionalization 1971-2011: Global Gendered Labor Markets”, foomi-net Working Papers No. 1, http://www.diasbola.com/uk/foomi-source.html European Culture and Society does makes reference to the rise of the female global sports star, beginning with Suzanne Lenglen's rather shocking appearance in short skirt, bandeau and sleeveless dress at Wimbledon in 1919 onwards. -

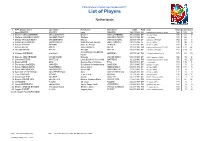

List of Players

FIFA Women's World Cup Canada 2015™ List of Players Netherlands # FIFA Display Name Last Name First Name Shirt Name DOB POS Club Height Caps Goals 1 Loes GEURTS GEURTS Loes GEURTS 12.01.1986 GK Kopparbergs/Goteborg FC (SWE) 168 103 0 2 Desiree VAN LUNTEREN VAN LUNTEREN Desiree VAN LUNTEREN 30.12.1992 DF AFC Ajax (NED) 170 21 0 3 Stefanie VAN DER GRAGT VAN DER GRAGT Stefanie VAN DER GRAGT 16.08.1992 DF Telstar (NED) 178 22 1 4 Mandy VAN DEN BERG VAN DEN BERG Mandy VAN DEN BERG 26.08.1990 DF LSK Kvinner FK (NOR) 165 57 3 5 Petra HOGEWONING HOGEWONING Petra Marieka Jacoba HOGEWONING 26.03.1986 DF AFC Ajax (NED) 170 96 0 6 Anouk DEKKER DEKKER Manieke Anouk DEKKER 15.11.1986 MF FC Twente (NED) 182 38 5 7 Manon MELIS MELIS Gabriella Maria MELIS 31.08.1986 FW Kopparbergs/Goteborg FC (SWE) 164 123 54 8 Sherida SPITSE SPITSE Sherida SPITSE 29.05.1990 MF LSK Kvinner FK (NOR) 167 104 15 Anna Margaretha Marina 9 Vivianne MIEDEMA MIEDEMA MIEDEMA 15.07.1996 FW FC Bayern München (GER) 175 23 19 Astrid 10 Danielle VAN DE DONK VAN DE DONK Daniëlle VAN DE DONK 05.08.1991 MF PSV/FC Eindhoven (NED) 160 35 6 11 Lieke MARTENS MARTENS Lieke Elisabeth Petronella MARTENS 16.12.1992 FW Kopparbergs/Goteborg FC (SWE) 170 49 20 12 Dyanne BITO BITO Dyanne Mary Christine BITO 10.08.1981 DF Telstar (NED) 163 146 6 13 Dominique JANSSEN JANSSEN Dominique Johanna Anna JANSSEN 17.01.1995 DF SGS Essen (GER) 174 6 0 14 Anouk HOOGENDIJK HOOGENDIJK Anouk Anna HOOGENDIJK 06.05.1985 DF AFC Ajax (NED) 170 101 9 15 Merel VAN DONGEN VAN DONGEN Merel Didi VAN DONGEN 11.02.1993 DF -

Årlig Genomgång Av Svensk Fotbollsekonomi Penningligan

Årlig genomgång av svensk fotbollsekonomi Penningligan Sports Business Group 2015 1 Allsvenskan slår omsättningsrekord igen, 1,3 miljarder SEK exklusive spelarförsäljningar 2 Innehåll Förord .................................... 4 Inblick individbeskattning ..... 24 Allsvenskans verksamhet, 1. Malmö FF ......................... 27 möjligheter och utmaningar ... 5 2. AIK ................................... 29 Allsvenskans intäkter ............. 5 3. BK Häcken ........................ 31 Allsvenskans kostnader .......... 7 4. IF Elfsborg ........................ 33 Årets resultat och eget kapital 7 5. IFK Göteborg .................... 35 Publik och nyttjande av arena . 8 6. Djurgårdens IF .................. 37 Intäktsgenerering ................... 9 7. IFK Norrköping ................. 39 Utmaningar för Allsvenskan .. 10 8. Kalmar FF ......................... 41 Jämförelse av klubbarnas verksamhet ........................... 12 9. Helsingborgs IF ................. 43 Penningligan ........................ 12 10.Örebro SK ........................ 45 Intäktsfördelning .................. 13 11. IF Brommapojkarna ........ 47 Klubbarnas kostnader ........... 14 12. Halmstad BK ................... 49 Personalkostnader ................ 14 13. Mjällby AIF ..................... 51 Snittintäkt per åskådare 14. Åtvidabergs FF ................ 53 och match ........................... 16 15. Falkenbergs FF................ 55 Publikligan ............................ 17 16. Gefle IF ........................... 57 Fördelning av sociala medier 18 Om rapporten -

World Soccer Records 2017 Free

FREE WORLD SOCCER RECORDS 2017 PDF Keir Radnedge | 256 pages | 03 Jan 2017 | Carlton Books | 9781780978642 | English | United States FIFA U World Cup - Wikipedia It medaled in every World Cup and Olympic tournament in women's soccer history from tobefore being knocked out in the quarterfinal of the Summer Olympics. After being ranked No. The team dropped to 2nd on March 24,due to its last-place finish in the SheBelieves Cupthen returned to 1st on June 23,after victories in friendlies against Russia, Sweden, and Norway. Olympic Committee's Team of the Year in and[5] and Sports Illustrated chose the entire team as Sportswomen of the Year for its usual Sportsman of the Year honor. Women's Soccer and U. Soccer reached a deal on a new collective bargaining agreement that would, among other things, lead to a pay increase. The passing of Title IX inwhich outlawed gender-based discrimination for federally-funded education programs, spurred the creation of college soccer teams across World Soccer Records 2017 United States at a time when women's soccer was rising in popularity World Soccer Records 2017. Soccer Federation tasked coach Mike Ryan to select a roster of college players to participate in the Mundialito tournament in Italy, its first foray into World Soccer Records 2017 international soccer. During the match, the style of play and athleticism of the United States ultimately won over the Italian fans. University of North Carolina coach Anson Dorrance was hired as World Soccer Records 2017 team's first full-time manager in with the goal of fielding a competitive women's team at the next Mundialito and at future tournaments. -

Multiple Documents

Alex Morgan et al v. United States Soccer Federation, Inc., Docket No. 2_19-cv-01717 (C.D. Cal. Mar 08, 2019), Court Docket Multiple Documents Part Description 1 3 pages 2 Memorandum Defendant's Memorandum of Points and Authorities in Support of i 3 Exhibit Defendant's Statement of Uncontroverted Facts and Conclusions of La 4 Declaration Gulati Declaration 5 Exhibit 1 to Gulati Declaration - Britanica World Cup 6 Exhibit 2 - to Gulati Declaration - 2010 MWC Television Audience Report 7 Exhibit 3 to Gulati Declaration - 2014 MWC Television Audience Report Alex Morgan et al v. United States Soccer Federation, Inc., Docket No. 2_19-cv-01717 (C.D. Cal. Mar 08, 2019), Court Docket 8 Exhibit 4 to Gulati Declaration - 2018 MWC Television Audience Report 9 Exhibit 5 to Gulati Declaration - 2011 WWC TElevision Audience Report 10 Exhibit 6 to Gulati Declaration - 2015 WWC Television Audience Report 11 Exhibit 7 to Gulati Declaration - 2019 WWC Television Audience Report 12 Exhibit 8 to Gulati Declaration - 2010 Prize Money Memorandum 13 Exhibit 9 to Gulati Declaration - 2011 Prize Money Memorandum 14 Exhibit 10 to Gulati Declaration - 2014 Prize Money Memorandum 15 Exhibit 11 to Gulati Declaration - 2015 Prize Money Memorandum 16 Exhibit 12 to Gulati Declaration - 2019 Prize Money Memorandum 17 Exhibit 13 to Gulati Declaration - 3-19-13 MOU 18 Exhibit 14 to Gulati Declaration - 11-1-12 WNTPA Proposal 19 Exhibit 15 to Gulati Declaration - 12-4-12 Gleason Email Financial Proposal 20 Exhibit 15a to Gulati Declaration - 12-3-12 USSF Proposed financial Terms 21 Exhibit 16 to Gulati Declaration - Gleason 2005-2011 Revenue 22 Declaration Tom King Declaration 23 Exhibit 1 to King Declaration - Men's CBA 24 Exhibit 2 to King Declaration - Stolzenbach to Levinstein Email 25 Exhibit 3 to King Declaration - 2005 WNT CBA Alex Morgan et al v. -

Redalyc.Three Types of Transnational Players: Differing Women's Football

Revista Brasileira de Ciências do Esporte ISSN: 0101-3289 [email protected] Colégio Brasileiro de Ciências do Esporte Brasil Tiesler, Nina Clara Three types of transnational players: differing women’s football mobility projects in core and developing countries Revista Brasileira de Ciências do Esporte, vol. 38, núm. 2, abril-junio, 2016, pp. 201-210 Colégio Brasileiro de Ciências do Esporte Curitiba, Brasil Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=401345786014 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Document downloaded from http://www.rbceonline.org.br day 06/06/2016. This copy is for personal use. Any transmission of this document by any media or format is strictly prohibited. Rev Bras Ciênc Esporte. 2016;38(2):201---210 Revista Brasileira de CIÊNCIAS DO ESPORTE www.rbceonline.org.br ORIGINAL ARTICLE Three types of transnational players: differing women’s football mobility projects in core and developing countries a,b Nina Clara Tiesler a Institute of Sociology, Leibniz University of Hannover, Hannover, Germany b Institute of Social Sciences, University of Lisbon, Lisbon, Portugal Received 20 October 2015; accepted 11 January 2016 Available online 5 March 2016 KEYWORDS Abstract Mobile players in men’s football are highly skilled professionals who move to a coun- Soccer; try other than the one where they grew up and started their careers. They are commonly Migration; described as migrants or expatriate players. -

June 2020 the International Journal Dedicated to Football

The international journal dedicated to football law # 13 - June 2020 Football Legal # 1 - June 2014 Special Report: Third Party Ownership (TPO) Football Legal # 2 - December 2014 Special Report: Financial Controls of Football Clubs Football Legal # 3 - June 2015 Special Report: The new Regulations on Working with Intermediaries Football Legal # 4 - December 2015 Special Report: International Football Justice Football Legal # 5 - June 2016 Special Report: TPO/TPI: an update Football Legal # 6 - November 2016 Special Report: Broadcasting & Media Rights in Football Leagues Football Legal # 7 - June 2017 Special Report: Minors in Football Football Legal # 8 - December 2017 Special Report: Data in Football Football Legal # 9 - June 2018 Special Report: Termination of Players’/Coaches’ Contracts Football Legal # 10 - December 2018 Special Report: Integrity in Football Football Legal # 11 - June 2019 Special Report: Major Football Competitions: Key Legal Challenges & Ongoing Reforms Football Legal # 12 - December 2019 Special Report: Private Football Academies Football Legal # 13 - June 2020 Special Report: Challenges in Football Facing COVID-19 Subscriptions: www.football-legal.com © Football Legal 2020 - All rights reserved worldwide ISSN: 2497-1219 EDITORIAL BOARD Saleh ALOBEIDLI Eugene KRECHETOV Lawyer, Saleh Alobeidli Advocates Lawyer, Eksports Law Dubai - UNITED ARAB EMIRATES Moscow - RUSSIA José Luis ANDRADE Andrew MERCER ECA General Counsel Acting General Counsel & Legal Director, AFC Nyon - SWITZERLAND Kuala Lumpur - MALAYSIA Nasr El -

1987-04-05 Liverpool

ARSENAL vLIVERPOOL thearsenalhistory.com SUNDAY 5th APRIL 1987 KICK OFF 3. 5pm OFFICIAL SOUVENIR "'~ £1 ~i\.c'.·'A': ·ttlewcrrJs ~ CHALLENGE• CUP P.O. CARTER, C.B.E. SIR JOHN MOORES, C.B.E. R.H.G. KELLY, F.C.l.S. President, The Football League President, The Littlewoods Organisation Secretary, The Football League 1.30 p.m. SELECTIONS BY THE BRISTOL UNICORNS YOUTH BAND (Under the Direction of Bandmaster D. A. Rogers. BEM) 2.15 p.m. LITTLEWOODS JUNIOR CHALLENGE Exhibition 6-A-Side Match organised by the National Association of Boys' Clubs featuring the Finalists of the Littlewoods Junior Challenge Cup 2.45 p.m. FURTHER SELECTIONS BY THE BRISTOL UNICORNS YOUTH BAND 3.05 p.m. PRESENTATION OF THE TEAMS TO SIR JOHN MOORES, C.B.E. President, The Littlewoods Organisation NATIONAL ANTHEM 3.15 p.m. KICK-OFF 4.00 p.m. HALF TIME Marching Display by the Bristol Unicorns Youth Band 4.55 p.m. END OF MATCH PRESENTATION OF THE LITTLEWOODS CHALLENGE CUP BY SIR JOHN MOORES Commemorative Covers The official commemorative cover for this afternoon's Littlewoods Challenge Cup match Arsenal v Liverpool £1.50 including post and packaging Wembley offers these superbly designed covers for most major matches played at the Stadium and thearsenalhistory.com has a selection of covers from previous League, Cup and International games available on request. For just £1.50 per year, Wembley will keep you up to date on new issues and back numbers, plus occasional bargain packs. MIDDLE TAR As defined by H.M. Government PLEASE SEND FOR DETAILS to : Mail Order Department, Wembley Stadium Ltd, Wembley, Warning: SMOKING CAN CAUSE HEART DISEASE Middlesex HA9 ODW Health Departments' Chief Medical Officers Front Cover Design by: CREATIVE SERVICES, HATFIELD 3 ltlewcms ARSENAL F .C. -

Goalden Times: December, 2011 Edition

GOALDEN TIMES 0 December, 2011 1 GOALDEN TIMES Declaration: The views and opinions expressed in this magazine are those of the authors of the respective articles and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of Goalden Times. All the logos and symbols of teams are the respective trademarks of the teams and national federations. The images are the sole property of the owners. However none of the materials published here can fully or partially be used without prior written permission from Goalden Times. If anyone finds any of the contents objectionable for any reasons, do reach out to us at [email protected]. We shall take necessary actions accordingly. Cover Illustration: Neena Majumdar & Srinwantu Dey Logo Design: Avik Kumar Maitra Design and Concepts: Tulika Das Website: www.goaldentimes.org Email: [email protected] Facebook: Goalden Times http://www.facebook.com/pages/GOALden-Times/160385524032953 Twitter: http://twitter.com/#!/goaldentimes December, 2011 GOALDEN TIMES 2 GT December 2011 Team P.S. Special Thanks to Tulika Das for her contribution in the Compile&Publish Process December, 2011 3 GOALDEN TIMES | Edition V | First Whistle …………5 Goalden Times is all set for the New Year Euro 2012 Group Preview …………7 Building up towards EURO 2012 in Poland-Ukraine, we review one group at a time, starting with Group A. Is the easiest group really 'easy'? ‘Glory’ – We, the Hunters …………18 The internet-based football forums treat them as pests. But does a glory hunter really have anything to be ashamed of? Hengul -

This Is Jmu Soccer

WELCOME A Message from the Coach Welcome to JMU women’s soccer. As the program’s first and only head coach, I am extremely proud of the history, tradition and reputation we have built here. Our players excel in the classroom, on the field and ultimately in the real world. Our schedule is always among the toughest because good players de- serve to test their talents against the best. JMU women’s soccer contin- ues to be one of the top programs in Virginia, in the CAA, the Mid-Atlantic region and in the nation… that is always our goal. Nestled in the beautiful Shenandoah Valley, JMU boasts tranquility, safety and a community that is committed to JMU athletics. The university has established itself with national rankings in many academic categories and is always evolving to chase its goal of being the best undergraduate univer- sity in the nation. This is a very dynamic time to be associated with JMU women’s soccer. I hope you will join us for an exciting season of soccer. Sincerely yours, Dave Lombardo Head Soccer Coach 2012 Schedule August 27 Northeastern*, 7 p.m. 9 at Virginia Tech (scrimmage), 6 p.m. 30 Hofstra*, 1 p.m. 12 Virginia Commonwealth (scrimmage), 6 p.m. 19 Marshall, 7 p.m. October 4 George Mason*, 7 p.m. JMU/Fairfield Inn by Marriott Invitational 7 at Towson*, 1 p.m. 24 Hofstra vs. Temple, 5 p.m. 11 at North Carolina Wilmington*, 7 p.m. JMU vs. Georgetown, 7:30 p.m. 14 at Georgia State*, 12 noon 26 Georgetown vs.