FOOMI-NET Working Paper No. 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Abcd Elena Fernández Aréizaga Curriculum Vitae

abcd Elena Fern´andezAr´eizaga Curriculum Vitae Diciembre 2019 1 1 Datos generales y situaci´onprofesional 2 1. Datos generales y situaci´onprofesional Apellidos: Fern´andezAr´eizaga Nombre: Elena DNI: 15915657W Fecha de nacimiento: 04/07/1956 Organismo: Universidad de C´adiz(UCA) Centro: Facultad de Ciencias Depto: Estad´ısticai Investigaci´oOperativa (EIO) Direccion´ postal: Pol´ıgonoR´ıoSan Pedro 11510 Puerto Real. Telefono:´ + 34 956 01 2783 Fax: + 34 956 01 6228 Correo electronico:´ [email protected] Categoria profesional: Catedr´aticode Universidad. (Fecha de inicio: 23-03-2007) Situacion´ administrativa: Plantilla Dedicacion:´ Tiempo completo Researcher ID: E-1799-2012 Codigo´ Orcid: 0000-0003-4714-0257 Especializacion´ (Codigos´ UNESCO): 1207/1203.26. (AMS 2010) 90C57, 90C10 L´ıneas de investigacion:´ Optimizaci´ondiscreta. Problemas discretos en redes. An´alisisde localizaci´on. Dise~node rutas de veh´ıculos. 1 Datos generales y situaci´onprofesional 3 Formaci´onacad´emica Titulacion´ Superior Centro Fecha Licenciatura de Matem´aticas Fac. Ciencias - Univ. Zaragoza 1979 Grado de Lic. Matem´aticas Fac. Ciencias - Univ. Valencia 1985 Doctorado Centro Fecha Doctora en Inform´atica Universitat Polit`ecnicade Catalunya 1988 Actividades anteriores de car´acteracad´emico Puesto Institucion´ Fechas Catedr´aticaUniversidad Dpt EIO - UPC 23-03-07 / 10-01-19 (dedicaci´onexclusiva) Prof. Titular Universidad Dpt EIO - UPC 01-02-89/ 22-03-07 (dedicaci´onexclusiva) Prof. Asociado a Tiempo Completo Fac. Inform`atica.Barcelona. UPC 01-10-87/ 31-01-89 (dedicaci´onexclusiva) Prof. Colaboradora Fac. Inform`atica.Barcelona. UPC 01-12-84 / 30-09-87 (dedicaci´onexclusiva) Prof. Colaboradora Fac. Inform´atica.San Sebasti´an 01-10-83/ 30-11-84 (dedicaci´onexclusiva) U. -

Uefa Women's Champions League

UEFA WOMEN'S CHAMPIONS LEAGUE - 2015/16 SEASON MATCH PRESS KITS Stadio Città del Tricolore - Reggio Emilia Thursday 26 May 2016 VfL Wolfsburg 18.00CET (18.00 local time) Olympique Lyonnais Matchday 14 - Final Last updated 25/05/2016 03:07CET UEFA WOMEN'S CHAMPIONS LEAGUE OFFICIAL SPONSORS Previous meetings 2 Match background 4 Squad list 6 Match officials 8 Fixtures and results 10 Match-by-match lineups 13 Legend 16 1 VfL Wolfsburg - Olympique Lyonnais Thursday 26 May 2016 - 18.00CET (18.00 local time) Match press kit Stadio Città del Tricolore, Reggio Emilia Previous meetings Head to Head UEFA Women's Champions League Date Stage Match Result Venue Goalscorers VfL Wolfsburg - Olympique 23/05/2013 F 1-0 London Müller 73 (P) Lyonnais Home Away Final Total Pld W D L Pld W D L Pld W D L Pld W D L GF GA VfL Wolfsburg 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 0 0 1 1 0 0 1 0 Olympique Lyonnais 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 1 1 0 0 1 0 1 VfL Wolfsburg - Record versus clubs from opponents' country UEFA Women's Champions League Date Stage Match Result Venue Goalscorers Paris Saint-Germain - VfL 1-2 Kaci 6; Müller 71, 26/04/2015 SF Paris Wolfsburg agg: 3-2 Jakabfi 74 VfL Wolfsburg - Paris Saint- Delannoy 12 (P), Cruz 18/04/2015 SF 0-2 Wolfsburg Germain Traña 26 Olympique Lyonnais - Record versus clubs from opponents' country UEFA Women's Champions League Date Stage Match Result Venue Goalscorers Olympique Lyonnais - 1. -

Aston Villa Women Vs Tottenham Hotspur Women Saturday 6Th February 2021 12.30Pm KO

Aston Villa Women vs Tottenham Hotspur Women Saturday 6th February 2021 12.30pm KO FAWSL ASTON VILLA WOMEN V TOTTENHAM HOTSPUR WOMEN EVERY GOAL EVERY CELEBRATION EVERY MOMENT EVERY TEAM FREE FOLLOW THE ACTION LIVE ON faplayer.thefa.com Column Coach’sGood afternoon and welcome to today’s Barclays FA Women’s Super League fixture versus Tottenham Hotspur. Anybody who watched Spurs last Sunday against So for all of our structure and organisation, we Chelsea would have seen a side who, for the first were unfortunately undone by the very basics of quarter of the game, got themselves into some football. really good goal-scoring opportunities against the current champions. The game got away from Like all good teams do, they exploited an area them before the break, and they will have been of improvement needed from ourselves and we disappointed that they didn’t make the most of as a staff will be looking today to see a shift in their chances at 0-0. mentality to do the basics better and continue to do the good things we did well. With that being said, we can’t hide the fact that this Spurs team suffered their first loss in seven We all know the supporters are kicking every ball last week, so this will be a difficult fixture for us to behind their TVs, laptops and smart phones. claim our first three points of the season at home. We just want you to know that we will go above Chelsea are ruthless, and even when they are not and beyond to work harder than we’ve ever at their best, they carry an array of talent and will worked before, and we will give everything to always pose a threat. -

Wm-Spezial • Schutzgebühr 1.- €

OFFIZIELLES MAGAZIN DER DEUTSCHEN FRAUEN-NATIONALMANNSCHAFT • WM-SPEZIAL • SCHUTZGEBÜHR 1.- € WM-Spezial www.dfb.dE www.fussball.DE all passion facebook.com/adidasfootball Liebe Zuschauerinnen und Zuschauer, der Countdown läuft unaufhörlich, die letzten Vorbereitungen für die FIFA Frauen-Welt- meisterschaft 2011 in Deutschland werden getroffen. Organisatorisch, vor allem aber sportlich. Je näher das Eröffnungsspiel am 26. Juni rückt, DEsto gespannter sind wir alle darauf, wie das Turnier verlaufen wird. Unser Team gehört sicher zu den Favoriten auf den Titelgewinn. Nach Erfolgen bei den vergangenen beiden Weltmeisterschaften kann es vor heimischer Kulisse auch gar nicht anders sein. Intensiv hat Trainerin Silvia Neid unserE Mannschaft auf dieses Turnier vorbereitet. Nichts wolltE sie dem Zufall überlassen, um bestmöglich in die WM gehen zu können. Dennoch warne ich davor, alles anderE als den Titelhattrick als eine Enttäuschung zu bezeichnen.Immerhinist,daswirDoftmalsvergessen,unserEFrauen-Nationalmannschaft nicht Erster der FIFA-Weltrangliste. Das sind die USA und nicht nur DEshalb zählt das Team von Trainerin Pia Sundhage für mich zu den großen Turnierfavoriten. Ebenso wie Brasilien, Schweden und Norwegen, Japan und vielleicht auch Nordkorea. Es gibt also fünf, sechs Teams, die auf einem sehr hohen Niveau spielen und der DFB-Auswahl das Leben schwer machen können. INHALT Viel wichtiger als der Titelgewinn ist es aber, dass unserE Mannschaft vor heimischer Grußwort von DFB-Präsident Dr. Theo Zwanziger 3 Kulisse über weitE Strecken modernen und ansehnlichen Fußball präsentiert, der die Das Ziel ist der Titel 4 Interview mit Bundespräsident Christian Wulff10 Fans auf den Rängen und vor den Fernsehschirmen begeistert. Auch das ist eine Grund- Prominente drücken dem Team die Daumen 12 lage für ein neues „Sommermärchen“. -

Uefa Europa League

UEFA EUROPA LEAGUE - 2020/21 SEASON MATCH PRESS KITS AZ Stadion - Alkmaar Thursday 26 November 2020 21.00CET (21.00 local time) AZ Alkmaar Group F - Matchday 4 Real Sociedad de Fútbol Last updated 24/11/2020 16:24CET Fixtures and results 2 Legend 6 1 AZ Alkmaar - Real Sociedad de Fútbol Thursday 26 November 2020 - 21.00CET (21.00 local time) Match press kit AZ Stadion, Alkmaar Fixtures and results AZ Alkmaar Date Competition Opponent Result Goalscorers Koopmeiners 90+5 (P), Guðmundsson 98 26/08/2020 UCL FC Viktoria Plzeň (H) W 3-1 aet ET, 118 ET 15/09/2020 UCL FC Dynamo Kyiv (A) L 0-2 19/09/2020 League PEC Zwolle (H) D 1-1 Boadu 68 26/09/2020 League SC Fortuna Sittard (A) D 3-3 D. De Wit 23, Koopmeiners 52, Boadu 69 04/10/2020 League Sparta Rotterdam (A) D 4-4 Aboukhlal 9, 19, D. De Wit 14, 33 17/10/2020 League VVV-Venlo (H) D 2-2 Karlsson 2, Stengs 24 22/10/2020 UEL SSC Napoli (A) W 1-0 D. De Wit 57 25/10/2020 League ADO Den Haag (A) D 2-2 Guðmundsson 33, Karlsson 66 Koopmeiners 6 (P), Guðmundsson 20, 60, 29/10/2020 UEL HNK Rijeka (H) W 4-1 Karlsson 51 01/11/2020 League RKC Waalwijk (H) W 3-0 Stengs 5, Guðmundsson 72, 90+1 05/11/2020 UEL Real Sociedad de Fútbol (A) L 0-1 Koopmeiners 29 (P), Woudenberg 41 (og), 08/11/2020 League sc Heerenveen (A) W 3-0 Karlsson 47 22/11/2020 League Emmen (H) W 1-0 Martins Indi 11 26/11/2020 UEL Real Sociedad de Fútbol (H) 29/11/2020 League Heracles Almelo (A) 03/12/2020 UEL SSC Napoli (H) 06/12/2020 League FC Groningen (H) 10/12/2020 UEL HNK Rijeka (A) 13/12/2020 League FC Twente (A) 20/12/2020 League -

Life with My Concussion

LIFE WITH MY CONCUSSION Author: Rianne Schorel Compiled & Written by Priyanka Iyer ianne Schorel was having a “ball” of a time with her soccer career. For sixteen years—both in the Netherlands and in the USA—she had been tasting the amazing successes of the game and went about Rclinching amazing wins. Her vigor for the game and the country was still raw. She was so close to fulfilling her dream of playing for the Dutch National Team, when during her debut game for the ADO Den Haag Club in February 2008, a close shot from one of her teammates led to a harsh hit on her head, resulting in a severe concussion and whiplash. Sustaining a TBI (Traumatic Brain Injury) changed the whole trajectory of her life. While soccer shaped Rianne into the person she is, TBI brought her to where she is today. Rianne, a distinguished former national soccer player from the Netherlands, went through motions of disbelief, pain, denial, and acceptance post-concussion—and emerged, phoenix- like, to take her life to a whole new level. LIFE WITH MY CONCUSSION New Expanded Edition A beautiful soccer career for myself, I had decided, But with reality, my dreams collided, While treading atop the peak of my career hill, A head injury brought everything to a standstill. I was a compass that had been stripped of its magnet, Could I let my dreams become stagnant? I was an athlete, and I could never quit, I had to bounce back from every hit. www.rianneschorel.com Copyright © 2017, 2018 Rianne Schorel All rights reserved. -

Curriculum Vitae

Bertrand MARESCHAL Brussels, October 10, 2014. 28 rue du Culot B - 1435 Mont Saint Guibert BELGIUM [email protected] http://homepages.ulb.ac.be/~bmaresc Phone: +32(475)716191 CURRICULUM VITAE Personal Record Date of birth: January 4, 1962. Birthplace: Brussels, Belgium. Civil status: Married, one child. Nationality: Belgian. Languages: French (native) English (fluent) Dutch (good level) Spanish (basic) Education • Classical primary and secondary (Latin-Greek) studies, Athénée Adolphe Max, Ville de Bruxelles, Belgium. • Licence en Sciences Mathématiques (4 year Master degree in mathematics), Brussels Free University (U.L.B.), Belgium, 1983, obtained with “La Plus Grande Distinction” (highest distinction). Thesis : « Etude théorique et pratique des méthodes de surclassement en analyse multicritère. » (multicriteria decision aid) • Licence en Sciences Actuarielles (Master degree in actuarial science), Brussels Free University (U.L.B.), Belgium, 1986, obtained with « La Plus Grande Distinction » (highest distinction). Thesis: "Développements récents de l'analyse multicritère : aspects théoriques et informatiques, applications bancaires et actuarielles." (multicriteria analysis in the banking and insurance sectors) • Doctorat en Sciences (doctorate in science - applied mathematics), Brussels Free University (U.L.B.), Belgium, 1989, obtained with "La Plus Grande Distinction" (highest distinction). Doctoral Thesis: "Aide à la décision multicritère : développements théoriques et applications (le système d'évaluation industrielle BANK ADVISER et -

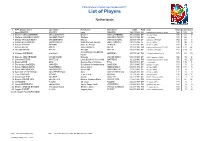

List of Players

FIFA Women's World Cup Canada 2015™ List of Players Netherlands # FIFA Display Name Last Name First Name Shirt Name DOB POS Club Height Caps Goals 1 Loes GEURTS GEURTS Loes GEURTS 12.01.1986 GK Kopparbergs/Goteborg FC (SWE) 168 103 0 2 Desiree VAN LUNTEREN VAN LUNTEREN Desiree VAN LUNTEREN 30.12.1992 DF AFC Ajax (NED) 170 21 0 3 Stefanie VAN DER GRAGT VAN DER GRAGT Stefanie VAN DER GRAGT 16.08.1992 DF Telstar (NED) 178 22 1 4 Mandy VAN DEN BERG VAN DEN BERG Mandy VAN DEN BERG 26.08.1990 DF LSK Kvinner FK (NOR) 165 57 3 5 Petra HOGEWONING HOGEWONING Petra Marieka Jacoba HOGEWONING 26.03.1986 DF AFC Ajax (NED) 170 96 0 6 Anouk DEKKER DEKKER Manieke Anouk DEKKER 15.11.1986 MF FC Twente (NED) 182 38 5 7 Manon MELIS MELIS Gabriella Maria MELIS 31.08.1986 FW Kopparbergs/Goteborg FC (SWE) 164 123 54 8 Sherida SPITSE SPITSE Sherida SPITSE 29.05.1990 MF LSK Kvinner FK (NOR) 167 104 15 Anna Margaretha Marina 9 Vivianne MIEDEMA MIEDEMA MIEDEMA 15.07.1996 FW FC Bayern München (GER) 175 23 19 Astrid 10 Danielle VAN DE DONK VAN DE DONK Daniëlle VAN DE DONK 05.08.1991 MF PSV/FC Eindhoven (NED) 160 35 6 11 Lieke MARTENS MARTENS Lieke Elisabeth Petronella MARTENS 16.12.1992 FW Kopparbergs/Goteborg FC (SWE) 170 49 20 12 Dyanne BITO BITO Dyanne Mary Christine BITO 10.08.1981 DF Telstar (NED) 163 146 6 13 Dominique JANSSEN JANSSEN Dominique Johanna Anna JANSSEN 17.01.1995 DF SGS Essen (GER) 174 6 0 14 Anouk HOOGENDIJK HOOGENDIJK Anouk Anna HOOGENDIJK 06.05.1985 DF AFC Ajax (NED) 170 101 9 15 Merel VAN DONGEN VAN DONGEN Merel Didi VAN DONGEN 11.02.1993 DF -

Abschiedsspiel Birgit Prinz Frauen-Nationalmannschaft 1.FFC Frankfurt

OFFIZIELLES MAGAZIN DER DEUTSCHEN FRAUEN-NATIONALMANNSCHAFT • 1/2012 • SCHUTZGEBÜHR 1.- € Abschiedsspiel Birgit Prinz Frauen-Nationalmannschaft 1.FFC Frankfurt Volksbank-Stadion Frankfurt 27.03.2012 www.dfb.de www.fussball.de 20 Jahre Partnerschaft Hol‘ Dir Dein offizielles DFB-Fan-Shirt zur EM! Jetzt Kassenbons von 8 Kästen Bitburger sammeln und gratis Dein individuelles DFB-Fan-Shirt sichern,* mit Deinem Namen, Deiner Wunschnummer und den gedruckten Unterschriften unserer Nationalmannschaft. Erhältlich ist es in zwei Größen. Mach mit! Alle Infos auf www.bitburger.de. Deutschland feiert die EM mit Bitburger – dem Bier unserer Nationalmannschaft und ihrer Fans. *20 x 0,5-l oder 24 x 0,33-l Bitburger (alle Sorten, kein Stubbi). Sammelzeitraum 19.03. bis 12.05.2012. Einsendeschluss ist der 14.05.2012. Tipp: Kassenbons bis zum 7. Mai einschicken und Shirt garantiert zum ersten Deutschland-Spiel erhalten! Teilnahme ab 18 Jahren. Erlebe jetzt den TV-Spot mit der Nationalmannschaft. Scanne diesen QR-Code mit einer Smartphone-App. wwww.bitburger.deww.bitburger.de Liebe Fans, ich bin kein Mensch der großen Worte. Daran wird sich auch anlässlich meines Abschiedsspiels nichts ändern. Trotzdem möchte ich die Gelegenheit nutzen, um mich aus drücklich bei Euch zu bedanken. Schließlich wart Ihr für mich auch Weggefährtinnen und -gefährten während meiner gesamten Karriere. Rückblickend kann ich sagen, dass es kein Spiel ohne Unterstützung von Euch gab. Überall und zu jeder Gelegenheit habe ich diese Begleitung wahrgenommen – Fahnen, Schals, Trikots gesehen oder Anfeuerung, Aufmunterung, Ermutigung gehört. Und zwar nicht nur bei den großen Spielen bei Welt- oder Europameisterschaften, Endspielen um den UEFA-Cup oder den DFB-Pokal, sondern auch bei Testspielen in kleineren Städten. -

Kick Off Your Career Turn Your Passion for Football Into Your Job Kick Off Your Career Kick Off Your Career

Kick off your career Turn your passion for football into your job Kick off your career Kick off your career Introduction As The FA celebrates 20 years of running women's The Football Association and the Women’s Sport and football huge progress has been made. You are one of Fitness Foundation have come together to show you how 1.4 million girls and women to play football regularly 20 women have succeeded in the football industry and up and down the country, but you can also have a how you can too. career in the sport that you love. This is the story of 20 women who ignored the stereotypes Two decades ago only men would be seen around and, in many cases, have become football pioneers. They the pitch or training ground, but now there are are women whose passion for the game has helped them female coaches, physiotherapists, doctors and sports to achieve extraordinary success. They come from all over scientists. Behind the scenes, there are female England with varied academic and social backgrounds; lawyers, accountants, club secretaries and chief they are all ages and come from different ethnic groups; executives; the press box on match days is sprinkled they are mothers, wives, daughters and sisters. with female reporters, and female directors now sit on the board at many top clubs. And that is not forgetting There are two things they have in common; they are the supporters, with more and more women and girls women who love football and they have turned their filling the seats in the football stadiums. -

Frauen-Bundesliga Extra • Schutzgebühr 1.- €

OFFIZIELLES MAGAZIN DES DEUTSCHEN FUSSBALL-BUNDES • FRAUEN-BUNDESLIGA EXTRA • SCHUTZGEBÜHR 1.- € Frauen-Bundesliga www.dfb.de www.fussball.de all passion facebook.com/adidasfootball Liebe Freunde des Fußballs, die FIFA Frauen-Weltmeisterschaft 2011 hat dem Frauenfußball in Deutschland eine enorme Aufmerksamkeit gebracht. 782.000 Zuschauer haben die Spiele live in den Stadien verfolgt, zudem haben das Fernsehen, der Hörfunk und die Presse umfangreich über das Turnier berichtet. Allein die wunderbaren TV-Einschaltquoten dokumentieren, mit welchem Interesse das Thema verfolgt wurde. All dies spiegelt eine sensationelle Rückmeldung für unseren Sport wider, aus der jeder, der sich in der Frauen-Bundesliga engagiert, neue Motivation für die Zukunft ziehen kann. Denn mit dem Start der Frauen-Bundesliga in die Saison 2011/2012 bietet sich die nächste Möglichkeit, den Frauenfußball von seiner schönsten Seite zu präsentieren. Schließlich steht diese Spielklasse für hochwertigen und attraktiven Sport. Auch wenn es der DFB- Auswahl nicht gelungen ist, den Traum vom dritten WM-Titelgewinn in Folge zu ver - wirklichen, bleibt die Bundesliga die Liga der Weltmeisterinnen. Nicht nur weil weiterhin viele Spielerinnen aktiv sind, die zu den WM-Triumphen 2003 und 2007 beigetragen haben, sondern auch weil in Saki Kamagui, Yuki Nagasato und Kozue Ando mittlerweile drei japanische Weltmeisterinnen ihre fußballerische Heimat in Deutschland gefun - den haben. Ihre Wechsel zu den Klubs der Frauen-Bundesliga sprechen für das Ansehen und die Leistungsstärke unserer Vereine. Das wird natürlich insbesondere durch die Vergleiche auf internationaler Ebene dokumentiert. Die Erfolge der deutschen Vertreter in der UEFA Women’s Champions League sind ein starkes Argument. In den zehn Jahren seit Bestehen des Wettbewerbs standen deutsche Klubs acht Mal im Endspiel und konnten sechs Mal den Titel gewinnen. -

Olympic Team Norway

Olympic Team Norway Media Guide Norwegian Olympic Committee NORWAY IN 100 SECONDS NOC OFFICIAL SPONSORS 2008 SAS Braathens Dagbladet TINE Head of state: Adidas H.M. King Harald V P4 H.M. Queen Sonja Adecco Nordea PHOTO: SCANPIX If... Norsk Tipping Area (total): Gyro Gruppen Norway 385.155 km2 - Svalbard 61.020 km2 - Jan Mayen 377 km2 Norway (not incl. Svalbard and Jan Mayen) 323.758 km2 Bouvet Island 49 km2 Peter Island 156 km2 NOC OFFICIAL SUPPLIERS 2008 Queen Maud Land Population (24.06.08) 4.768.753 Rica Hertz Main cities (01.01.08) Oslo 560.484 Bergen 247.746 Trondheim 165.191 Stavanger 119.586 Kristiansand 78.919 CLOTHES/EQUIPMENTS/GIFTS Fredrikstad 71.976 TO THE NORWEGIAN OLYMPIC TEAM Tromsø 65.286 Sarpsborg 51.053 Adidas Life expectancy: Men: 77,7 Women: 82,5 RiccoVero Length of common frontiers: 2.542 km Silhouette - Sweden 1.619 km - Finland 727 km Jonson&Jonson - Russia 196 km - Shortest distance north/south 1.752 km Length of the continental coastline 21.465 km - Not incl. Fjords and bays 2.650 km Greatest width of the country 430 km Least width of the country 6,3 km Largest lake: Mjøsa 362 km2 Longest river: Glomma 600 km Highest waterfall: Skykkjedalsfossen 300 m Highest mountain: Galdhøpiggen 2.469 m Largest glacier: Jostedalsbreen 487 km2 Longest fjord: Sognefjorden 204 km Prime Minister: Jens Stoltenberg Head of state: H.M. King Harald V and H.M. Queen Sonja Monetary unit: NOK (Krone) 16.07.08: 1 EUR = 7,90 NOK 100 CNY = 73,00 NOK NORWAY’S TOP SPORTS PROGRAMME On a mandate from the Norwegian Olympic Committee (NOK) and Confederation of Sports (NIF) has been given the operative responsibility for all top sports in the country.