Alfred Deakin's Letters to the London Morning Post

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RACIAL EQUALITY BILL: JAPANESE PROPOSAL at PARIS PEACE CONFERENCE: DIPLOMATIC MANOEUVRES; and REASONS for REJECTION by Shizuka

RACIAL EQUALITY BILL: JAPANESE PROPOSAL AT PARIS PEACE CONFERENCE: DIPLOMATIC MANOEUVRES; AND REASONS FOR REJECTION By Shizuka Imamoto B.A. (Hiroshima Jogakuin University, Japan), Graduate Diploma in Language Teaching (University of Technology Sydney, Australia) A thesis submitted for the degree of Master of Arts (Honours) at Macquarie University. Japanese Studies, Department of Asian Languages, Division of Humanities, College of Humanities and Social Sciences, Macquarie University, Sydney Australia. 2006 DECLARATION I declare that the present research work embodied in the thesis entitled, Racial Equality Bill: Japanese Proposal At Paris Peace Conference: Diplomatic Manoeuvres; And Reasons For Rejection was carried out by the author at Macquarie Japanese Studies Centre of Macquarie University of Sydney, Australia during the period February 2003 to February 2006. This work has not been submitted for a higher degree to any other university or institution. Any published and unpublished materials of other writers and researchers have been given full acknowledgement in the text. Shizuka Imamoto ii TABLE OF CONTENTS DECLARATION ii TABLE OF CONTENTS iii SUMMARY ix DEDICATION x ACKNOWLEDGEMENT xi INTRODUCTION 1 1. Area Of Study 1 2. Theme, Principal Question, And Objective Of Research 5 3. Methodology For Research 5 4. Preview Of The Results Presented In The Thesis 6 End Notes 9 CHAPTER ONE ANGLO-JAPANESE RELATIONS AND WORLD WAR ONE 11 Section One: Anglo-Japanese Alliance 12 1. Role Of Favourable Public Opinion In Britain And Japan 13 2. Background Of Anglo-Japanese Alliance 15 3. Negotiations And Signing Of Anglo-Japanese Alliance 16 4. Second Anglo-Japanese Alliance 17 5. Third Anglo-Japanese Alliance 18 Section Two: Japan’s Involvement In World War One 19 1. -

Rural Ararat Heritage Study Volume 4

Rural Ararat Heritage Study Volume 4. Ararat Rural City Thematic Environmental History Prepared for Ararat Rural City Council by Dr Robyn Ballinger and Samantha Westbrooke March 2016 History in the Making This report was developed with the support PO Box 75 Maldon VIC 3463 of the Victorian State Government RURAL ARARAT HERITAGE STUDY – VOLUME 4 THEMATIC ENVIRONMENTAL HISTORY Table of contents 1.0 Introduction 1 1.1 The study area 1 1.2 The heritage significance of Ararat Rural City's landscape 3 2.0 The natural environment 4 2.1 Geomorphology and geology 4 2.1.1 West Victorian Uplands 4 2.1.2 Western Victorian Volcanic Plains 4 2.2 Vegetation 5 2.2.1 Vegetation types of the Western Victorian Uplands 5 2.2.2 Vegetation types of the Western Victoria Volcanic Plains 6 2.3 Climate 6 2.4 Waterways 6 2.5 Appreciating and protecting Victoria’s natural wonders 7 3.0 Peopling Victoria's places and landscapes 8 3.1 Living as Victoria’s original inhabitants 8 3.2 Exploring, surveying and mapping 10 3.3 Adapting to diverse environments 11 3.4 Migrating and making a home 13 3.5 Promoting settlement 14 3.5.1 Squatting 14 3.5.2 Land Sales 19 3.5.3 Settlement under the Land Acts 19 3.5.4 Closer settlement 22 3.5.5 Settlement since the 1960s 24 3.6 Fighting for survival 25 4.0 Connecting Victorians by transport 28 4.1 Establishing pathways 28 4.1.1 The first pathways and tracks 28 4.1.2 Coach routes 29 4.1.3 The gold escort route 29 4.1.4 Chinese tracks 30 4.1.5 Road making 30 4.2 Linking Victorians by rail 32 4.3 Linking Victorians by road in the 20th -

House of Representatives

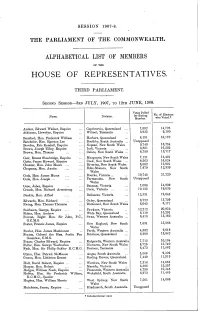

SESSION 1907-8. THE PARLIAMENT OF THE COMMONWEALTH. ALPHABETICAL LIST OF MEMBERS OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES. THIRD PARLIAMENT. SECOND SESSION-3RD JULY, 1907, TO 12TH JUNE, 1908. Votes Polled No. of Electors Name. Division. for Sitting Member. who Voted.* Archer, Edward Walker, Esquire Capricornia, Queensland ... 7,892 14,725 Atkinson, Llewelyn, Esquire Wilmot, Tasmania 3,935 9,100 Bamford, Hon. Frederick William Herbert, Queensland ... 8,151 16,170 Batchelor, Hon. Egerton Lee Boothby, South Australia ... Unopposed Bowden, Eric Kendall, Esquire Nepean, New South Wales 9,749 16,754 Brown, Joseph Tilley, Esquire Indi, Victoria 6,801 16,205 Brown, Hon. Thomas ... Calare, New South Wales ... 6,759 13,717 Carr, Ernest Shoobridge, Esquire Macquarie, New South Wales 7,121 14,401 Catts, James Howard, Esquire Cook, New South Wales .. 8,563 16,624 Chanter, Hon. John Moore ... Riverina, New South Wales 6,662 12,921 Chapman, Hon. Austin ... Eden-Monaro, New South 7,979 12,339 Wales Cook, Hon. James Hume ... Bourke, Victoria ... 10,745 21,220 Cook, Hon. Joseph ... Parramatta, New South Unopposed Wales Coon, Jabez, Esquire Batman, Victoria 7,098 14,939 Crouch, Hon. Richard Armstrong Corio, Victoria ... 10,135 19,035 Deakin, Hon. Alfred Ballaarat, Victoria 12,331 19,048 Edwards, Hon. Richard Oxley, Queensland 8,722 13,729 8,171 Ewing, Hon. Thomas Thomson Richmond, New South Wales 6,042 Fairbairn, George, Esquire ... Fawkner, Victoria 12,212 20,952 Fisher, Hon. Andrew ... Wide Bay, Queensland 8,118 15,291 Forrest, Right Hon. Sir John, P.C., Swan, Western Australia ... 8,418 13,163 G.C.M.G. -

Mr William Benjamin Chaffey

STATE LIBRARY OF SOUTH AUSTRALIA J. D. SOMERVILLE ORAL HISTORY COLLECTION OH 692/21 Full transcript of an interview with MR WILLIAM BENJAMIN CHAFFEY on 5 March 2003 by Rob Linn Recording available on CD Access for research: Unrestricted Right to photocopy: Copies may be made for research and study Right to quote or publish: Publication only with written permission from the State Library OH 692/21 MR WILLIAM BENJAMIN CHAFFEY NOTES TO THE TRANSCRIPT This transcript was donated to the State Library. It was not created by the J.D. Somerville Oral History Collection and does not necessarily conform to the Somerville Collection's policies for transcription. Readers of this oral history transcript should bear in mind that it is a record of the spoken word and reflects the informal, conversational style that is inherent in such historical sources. The State Library is not responsible for the factual accuracy of the interview, nor for the views expressed therein. As with any historical source, these are for the reader to judge. This transcript had not been proofread prior to donation to the State Library and has not yet been proofread since. Researchers are cautioned not to accept the spelling of proper names and unusual words and can expect to find typographical errors as well. 2 OH 692/21 TAPE 1 - SIDE A AUSTRALIAN WINE ORAL HISTORY PROJECT. Interview with Mr William Benjamin Chaffey on 5th March, 2003. Interviewer: Rob Linn. Well, Mr Chaffey, where and when were you born? BC: I was born in Whittier, California, on November 12th, 1914. -

The Influence of the Friendly Society Movement in Victoria 1835–1920

The Influence of the Friendly Society Movement in Victoria 1835–1920 Roland S. Wettenhall Post Grad. Dip. Arts A thesis submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 24 June 2019 Faculty of Arts School of Historical and Philosophical Studies The University of Melbourne ABSTRACT Entrepreneurial individuals who migrated seeking adventure, wealth and opportunity initially stimulated friendly societies in Victoria. As seen through the development of friendly societies in Victoria, this thesis examines the migration of an English nineteenth-century culture of self-help. Friendly societies may be described as mutually operated, community-based, benefit societies that encouraged financial prudence and social conviviality within the umbrella of recognised institutions that lent social respectability to their members. The benefits initially obtained were sickness benefit payments, funeral benefits and ultimately medical benefits – all at a time when no State social security systems existed. Contemporaneously, they were social institutions wherein members attended regular meetings for social interaction and the friendship of like-minded individuals. Members were highly visible in community activities from the smallest bush community picnics to attendances at Royal visits. Membership provided a social caché and well as financial peace of mind, both important features of nineteenth-century Victorian society. This is the first scholarly work on the friendly society movement in Victoria, a significant location for the establishment of such societies in Australia. The thesis reveals for the first time that members came from all strata of occupations, from labourers to High Court Judges – a finding that challenges conventional wisdom about the class composition of friendly societies. -

Votes and Proceedings House of Representatives

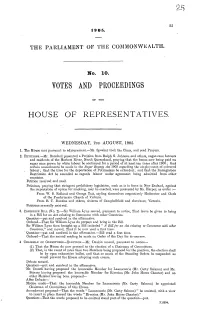

25 1905. THE PARLIAMENT OF THE COMMONWEALTH. No. 10. VOTES AND PROCEEDINGS OF TIIE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES. WEDNESDAY, 2ND AUGUST, 1905. 1. The House met pursuant to adjournment.-Mr. Speaker took the Chair, and read Prayers. 2. PETITIONS.-Mr. Bamford presented a Petition from Ralph G. Johnson and others, sugar-cane farmers and residents of the Herbert River, North Queensland, praying that the bonus now being paid on sugar cane grown by white labour be continued for a period of at least ten years after 1906; that certain amendments be made in the Sugar Bounty Act 1903 regarding the employment of coloured labour; that the time for the deportation of Polynesians be extended ; and that the Immigration Restriction Act be amended as regards labour under agreement being admitted from other countries. Petition received and read. Petitions, praying that stringent prohibitory legislation, such as is in force in New Zealand, against the importation of opium for smoking, may be enacted, were presented by Mr. Harper, as under :- From W. S. Rolland and George Tait, styling themselves respectively Moderator and Clerk of the Presbyterian Church of Victoria. From B. T. Buntine and others, citizens of Campbellfield and elsewhere, Victoria. Petitions severally received. 3. COMMERCE BILL (NO. 2).-Sir William Lyne moved, pursuant to notice, That leave be given to bring in a Bill for an Act relating to Commerce with other Countries. Question-put and resolved in the affirmative. Ordered-That Sir William Lyne do prepare and bring in the Bill. Sir William Lyne then brought up a Bill intituled " A Bill for an Act relating to Commerce with other Countries," and moved, That it be now read a first time. -

The Children Overboard Event: Constructing the Family and Nation Through Representations of the Other

Edith Cowan University Research Online Theses : Honours Theses 2002 The children overboard event: Constructing the family and nation through representations of the other Kate Slattery Edith Cowan University Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses_hons Part of the Critical and Cultural Studies Commons, and the Gender, Race, Sexuality, and Ethnicity in Communication Commons Recommended Citation Slattery, K. (2002). The children overboard event: Constructing the family and nation through representations of the other. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses_hons/569 This Thesis is posted at Research Online. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses_hons/569 Edith Cowan University Copyright Warning You may print or download ONE copy of this document for the purpose of your own research or study. The University does not authorize you to copy, communicate or otherwise make available electronically to any other person any copyright material contained on this site. You are reminded of the following: Copyright owners are entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. A reproduction of material that is protected by copyright may be a copyright infringement. Where the reproduction of such material is done without attribution of authorship, with false attribution of authorship or the authorship is treated in a derogatory manner, this may be a breach of the author’s moral rights contained in Part IX of the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth). Courts have the power to impose a wide range of civil and criminal sanctions for infringement of copyright, infringement of moral rights and other offences under the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth). Higher penalties may apply, and higher damages may be awarded, for offences and infringements involving the conversion of material into digital or electronic form. -

LORD HOPETOUN Papers, 1853-1904 Reels M936-37, M1154

AUSTRALIAN JOINT COPYING PROJECT LORD HOPETOUN Papers, 1853-1904 Reels M936-37, M1154-56, M1584 Rt. Hon. Marquess of Linlithgow Hopetoun House South Queensferry Lothian Scotland EH30 9SL National Library of Australia State Library of New South Wales Filmed: 1973, 1980, 1983 BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE John Adrian Louis Hope (1860-1908), 7th Earl of Hopetoun (succeeded 1873), 1st Marquess of Linlithgow (created 1902), was born at Hopetoun House, near Edinburgh. He was educated at Eton and the Royal Military College, Sandhurst, but did not enter the Army. In 1883 he was appointed Conservative whip in the House of Lords and in 1885 was made a lord-in-waiting to Queen Victoria. In 1886 he married Hersey Moleyns, the daughter of Lord Ventry. In 1889 Lord Knutsford, the Secretary of State for the Colonies, appointed Hopetoun as Governor of Victoria and he held the post until March 1895. Although it was a time of economic depression, he entertained extravagantly, but his youthful enthusiasm and fondness for horseback tours of country districts won him considerable popularity. His term coincided with the first federation conferences and he supported the federation movement strongly. In 1895-98 Hopetoun was paymaster-general in the government of Lord Salisbury. In 1898 Joseph Chamberlain, the Secretary of State for the Colonies, offered him the post of Governor-General of Canada, but he declined. He was appointed Lord Chamberlain in 1898 and had a close association with members of the Royal Family. In July 1900 Hopetoun was appointed the first Governor-General of the Commonwealth of Australia. He arrived in Sydney on 15 December 1900 and his first task was to appoint the head of the new Commonwealth ministry. -

The Life and Times of Sir John Waters Kirwan (1866-1949)

‘Mightier than the Sword’: The Life and Times of Sir John Waters Kirwan (1866-1949) By Anne Partlon MA (Eng) and Grad. Dip. Ed This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of Murdoch University 2011 I declare that this thesis is my own account of my research and contains as its main content work which has not been previously submitted for a degree at any tertiary education institution. ............................................................... Anne Partlon ii Table of Contents Abstract iv Acknowledgements v Introduction: A Most Unsuitable Candidate 1 Chapter 1:The Kirwans of Woodfield 14 Chapter 2:‘Bound for South Australia’ 29 Chapter 3: ‘Westward Ho’ 56 Chapter 4: ‘How the West was Won’ 72 Chapter 5: The Honorable Member for Kalgoorlie 100 Chapter 6: The Great Train Robbery 120 Chapter 7: Changes 149 Chapter 8: War and Peace 178 Chapter 9: Epilogue: Last Post 214 Conclusion 231 Bibliography 238 iii Abstract John Waters Kirwan (1866-1949) played a pivotal role in the Australian Federal movement. At a time when the Premier of Western Australia Sir John Forrest had begun to doubt the wisdom of his resource rich but under-developed colony joining the emerging Commonwealth, Kirwan conspired with Perth Federalists, Walter James and George Leake, to force Forrest’s hand. Editor and part- owner of the influential Kalgoorlie Miner, the ‘pocket-handkerchief’ newspaper he had transformed into one of the most powerful journals in the colony, he waged a virulent press campaign against the besieged Premier, mocking and belittling him at every turn and encouraging his east coast colleagues to follow suit. -

Papers on Parliament No. 30

Sir Richard Chaffey Baker—the Senate’s First Republican Sir Richard Chaffey Baker—the Senate’s First Republican* Mark McKenna ate last year I received a phone call from Sue Rickard, then Senior Research Officer in Lthe Department of the Senate. Sue had seen my book The Captive Republic and expressed her surprise at the reference in the book to Richard Chaffey Baker in the chapter on federation and republicanism.1 I had claimed Baker as a republican—a description which I decided would provide an apt if not slightly mischievous title for today’s lecture. Sue asked if I would be interested in delivering a lecture on Baker—the first President of the Senate and perhaps explaining along the way how it was that one of South Australia’s most conservative politicians—a member of the Adelaide Club and a man who frequently boasted of his loyalty to the crown, could be a republican. I had little idea when I agreed to Sue’s request just how useful and interesting a lens Baker’s political life would prove to be. As we progress tentatively towards an explicitly republican form of government, it seems appropriate to reflect on the views of one of Australia’s forgotten founders. It is typical of Australia’s political history that one of the most pivotal figures in the federation period is a relatively unknown figure. In the United States, a person of similar political stature to Baker would have received far more attention. This brings to mind a comment recently made by Humphrey McQueen in his book Suspect History. -

Votes and Proceedings House of Representatives

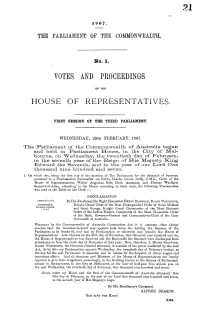

I 9 0 7. THE PARLIAMENT OF THE COMMONWEALTH. No. 1. VOTES AND PROCEEDINGS OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES. FIRST SESSION OF THE THIRD PARLIAMENT. WEDNESDAY, 20TH FEBRUARY, 1907. The Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia begun and held in Parliament House, in the City of MSel- bourne, on Wednesday, the twentieth day of February, in the seventh year of the Reign of His Majesty King Edward the Seventh, and in the year of our Lord One thousand nine hundred and seven. 1. On which day, being the first day of the meeting of The Parliament for the despatch of business, pursuant to a Proclamation (hereinafter set forth), Charles Gavan Duffy, C.M.G., Clerk of the House of Representatives, Walter Augustus Gale, Clerk Assistant, and Thomas Woollard, Serjeant-at-Arms, attending in the House according to their duty, the following Proclamation was read at the Table by the Clerk :- PROCLAMATION Australia to wit. By His Excellencythe Right Honorable HENRY STAFFORD, BARON NORTIICOTE, NORTHCOTE, Knight Grand Cross of the Most Distinguished Order of Saint Michael Oovcrn,,.cni. and Saint George, Knight Grand Commander of the Most Eminent Order of the Indian Empire, Companion of the Most Honorable Order of the Bath, Governor-General and Commander-in-Chief of the Com- nionwealth of Australia. WHEREAS by the Commonwealth of Australia Constitution Act it is amongst other things enacted that the Governor-General may appoint such times for holding the Sessions of the Parliament as he thinks fit, and also by Proclamation or otherwise may dissolve the House -

Richard Chaffey Baker and the Shaping Of

Richard Chaffey Baker and the Shaping Rosemary Laing of the Senate It was Harry Evans who first introduced me to Sir Richard Chaffey Baker—or ‘Dickie’ Baker as he fondly called him—the first President of the Australian Senate. Baker, though a native-born South Australian, had been educated at Eton, Cambridge and Lincoln’s Inn, but had gone on to be an influential delegate at the constitutional conventions of the 1890s, bucking the standard colonial obeisance to all things Westminster. Like Tasmanian Andrew Inglis Clark and a few others, Baker questioned the very rationale of the theory of responsible government while promoting something rather more republican in character, though always under the British Crown.1 When the Senate Department’s major Centenary of Federation project, the four-volume Biographical Dictionary of the Australian Senate, began to get off the ground in the early 1990s under the indefatigable editorship of Ann Millar, four sample entries were prepared to illustrate how the project could be done and what the entries would look like. An entry on Baker, researched and written by Dr Margot Kerley, was one of those four pilot entries. Perhaps it was a strategic choice given Harry Evans’ great interest in the subject, but Harry needed little convincing that this was a worthwhile contribution to the history of federation and he remained the dictionary’s strongest supporter, particularly at Senate estimates. Harry also read all entries, continuing to do so even after retiring, bringing to the task his great critical faculties and his unrivalled knowledge of Australian political history.