A History of Management in Australia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Around the Bend

Cultural Studies Review volume 18 number 1 March 2012 http://epress.lib.uts.edu.au/journals/index.php/csrj/index pp. 86–106 Emily Bullock 2012 Around the Bend The Curious Power of the Hills around Queenstown, Tasmania EMILY BULLOCK UNIVERSITY OF TASMANIA Approaching the town of Queenstown you can’t help but be taken aback by the sight of the barren hillsides, hauntingly bare yet strangely beautiful. This lunar landscape has a majestic, captivating quality. In December 1994 after 101 years of continuous mining—A major achievement for a mining company—the Mount Lyell Mining and Railway Company called it a day and closed the operation thus putting Queenstown under threat of becoming a ghost town. Now, with the mine under the ownership of Copper Mines of Tasmania, the town and the mine are once again thriving. Although Queenstown is primarily a mining town, it is also a very popular tourist destination offering visitors unique experiences. So, head for the hills and discover Queenstown—a unique piece of ‘Space’ on earth.1 In his discussion of the labour of the negative in Defacement: Public Secrecy and the Labour of the Negative, Michael Taussig opens out into a critique of criticism. ISSN 1837-8692 Criticism, says Taussig, is in some way a defacement, a tearing away at an object that ends up working its magic on the critic and forging a ‘curious complicity’ between object and critic.2 Taussig opens up a critical space in which to think with the object of analysis, cutting through transcendental critique, as a critical defacement, which, in the very act of cutting, produces negative energy: a ‘contagious, proliferating, voided force’ in which the small perversities of ‘laughter, bottom-spanking, eroticism, violence, and dismemberment exist simultaneously in violent silence’.3 This complicity in thinking might be charged by critical methodologies which engage in, and think through, peripatetic movements. -

No Ordinary Place. No Ordinary Festival

Queenstown, Tasmania | 14–16 October 2016 | theunconformity.com.au No ordinary place. No ordinary festival. 1 WELCOME TO QUEENSTOWN and Tasmania’s West IN 2016, The Unconformity will once again Coast for The Unconformity. This festival is really like no bring an exciting program of contemporary arts other, one that must be experienced to be believed. experiences to Queenstown and surrounds. These arts experiences are as varied and An unconformity is an area of rock that shows a geological unique as the voices they represent with works break in time. The Unconformity Festival bridges every by local, national and international artists. layer of the West Coast and, like its geological namesake, indicates a break in the region’s past and present. It brings The value the Festival brings to the Queenstown the community together to celebrate Queenstown’s rugged community is significant. It encourages backbone, unique arts culture and unmatched sense of place. community members to come together and participate in the arts and the calibre of its This year’s festival program showcases local, interstate program attracts more visitors to the region and overseas artists to present a weekend for everyone each biennial year. The Unconformity compels to enjoy. It is as dramatic as the surrounding landscape. visitors to engage with and explore the unique The Tasmanian Government is proud to support The region that is Tasmania’s remote West Coast, Unconformity in 2016. Congratulations to the team behind drawing them back again and again. the festival who, along with the Queenstown community, Over the past six years, the festival bring this extraordinary mix of arts and heritage together has flourished and grown and is now a for all of us to embrace. -

Rural Ararat Heritage Study Volume 4

Rural Ararat Heritage Study Volume 4. Ararat Rural City Thematic Environmental History Prepared for Ararat Rural City Council by Dr Robyn Ballinger and Samantha Westbrooke March 2016 History in the Making This report was developed with the support PO Box 75 Maldon VIC 3463 of the Victorian State Government RURAL ARARAT HERITAGE STUDY – VOLUME 4 THEMATIC ENVIRONMENTAL HISTORY Table of contents 1.0 Introduction 1 1.1 The study area 1 1.2 The heritage significance of Ararat Rural City's landscape 3 2.0 The natural environment 4 2.1 Geomorphology and geology 4 2.1.1 West Victorian Uplands 4 2.1.2 Western Victorian Volcanic Plains 4 2.2 Vegetation 5 2.2.1 Vegetation types of the Western Victorian Uplands 5 2.2.2 Vegetation types of the Western Victoria Volcanic Plains 6 2.3 Climate 6 2.4 Waterways 6 2.5 Appreciating and protecting Victoria’s natural wonders 7 3.0 Peopling Victoria's places and landscapes 8 3.1 Living as Victoria’s original inhabitants 8 3.2 Exploring, surveying and mapping 10 3.3 Adapting to diverse environments 11 3.4 Migrating and making a home 13 3.5 Promoting settlement 14 3.5.1 Squatting 14 3.5.2 Land Sales 19 3.5.3 Settlement under the Land Acts 19 3.5.4 Closer settlement 22 3.5.5 Settlement since the 1960s 24 3.6 Fighting for survival 25 4.0 Connecting Victorians by transport 28 4.1 Establishing pathways 28 4.1.1 The first pathways and tracks 28 4.1.2 Coach routes 29 4.1.3 The gold escort route 29 4.1.4 Chinese tracks 30 4.1.5 Road making 30 4.2 Linking Victorians by rail 32 4.3 Linking Victorians by road in the 20th -

Mount Lyell Abt Railway Tasmania

Mount Lyell Abt Railway Tasmania Nomination for Engineers Australia Engineering Heritage Recognition Volume 2 Prepared by Ian Cooper FIEAust CPEng (Retired) For Abt Railway Ministerial Corporation & Engineering Heritage Tasmania July 2015 Mount Lyell Abt Railway Engineering Heritage nomination Vol2 TABLE OF CONTENTS BIBLIOGRAPHIES CLARKE, William Branwhite (1798-1878) 3 GOULD, Charles (1834-1893) 6 BELL, Charles Napier, (1835 - 1906) 6 KELLY, Anthony Edwin (1852–1930) 7 STICHT, Robert Carl (1856–1922) 11 DRIFFIELD, Edward Carus (1865-1945) 13 PHOTO GALLERY Cover Figure – Abt locomotive train passing through restored Iron Bridge Figure A1 – Routes surveyed for the Mt Lyell Railway 14 Figure A2 – Mount Lyell Survey Team at one of their camps, early 1893 14 Figure A3 – Teamsters and friends on the early track formation 15 Figure A4 - Laying the rack rail on the climb up from Dubbil Barril 15 Figure A5 – Cutting at Rinadeena Saddle 15 Figure A6 – Abt No. 1 prior to dismantling, packaging and shipping to Tasmania 16 Figure A7 – Abt No. 1 as changed by the Mt Lyell workshop 16 Figure A8 – Schematic diagram showing Abt mechanical motion arrangement 16 Figure A9 – Twin timber trusses of ‘Quarter Mile’ Bridge spanning the King River 17 Figure A10 – ‘Quarter Mile’ trestle section 17 Figure A11 – New ‘Quarter Mile’ with steel girder section and 3 Bailey sections 17 Figure A12 – Repainting of Iron Bridge following removal of lead paint 18 Figure A13 - Iron Bridge restoration cross bracing & strengthening additions 18 Figure A14 – Iron Bridge new -

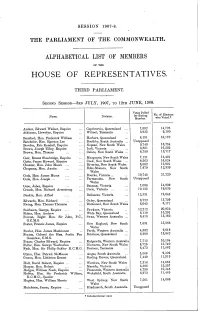

House of Representatives

SESSION 1907-8. THE PARLIAMENT OF THE COMMONWEALTH. ALPHABETICAL LIST OF MEMBERS OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES. THIRD PARLIAMENT. SECOND SESSION-3RD JULY, 1907, TO 12TH JUNE, 1908. Votes Polled No. of Electors Name. Division. for Sitting Member. who Voted.* Archer, Edward Walker, Esquire Capricornia, Queensland ... 7,892 14,725 Atkinson, Llewelyn, Esquire Wilmot, Tasmania 3,935 9,100 Bamford, Hon. Frederick William Herbert, Queensland ... 8,151 16,170 Batchelor, Hon. Egerton Lee Boothby, South Australia ... Unopposed Bowden, Eric Kendall, Esquire Nepean, New South Wales 9,749 16,754 Brown, Joseph Tilley, Esquire Indi, Victoria 6,801 16,205 Brown, Hon. Thomas ... Calare, New South Wales ... 6,759 13,717 Carr, Ernest Shoobridge, Esquire Macquarie, New South Wales 7,121 14,401 Catts, James Howard, Esquire Cook, New South Wales .. 8,563 16,624 Chanter, Hon. John Moore ... Riverina, New South Wales 6,662 12,921 Chapman, Hon. Austin ... Eden-Monaro, New South 7,979 12,339 Wales Cook, Hon. James Hume ... Bourke, Victoria ... 10,745 21,220 Cook, Hon. Joseph ... Parramatta, New South Unopposed Wales Coon, Jabez, Esquire Batman, Victoria 7,098 14,939 Crouch, Hon. Richard Armstrong Corio, Victoria ... 10,135 19,035 Deakin, Hon. Alfred Ballaarat, Victoria 12,331 19,048 Edwards, Hon. Richard Oxley, Queensland 8,722 13,729 8,171 Ewing, Hon. Thomas Thomson Richmond, New South Wales 6,042 Fairbairn, George, Esquire ... Fawkner, Victoria 12,212 20,952 Fisher, Hon. Andrew ... Wide Bay, Queensland 8,118 15,291 Forrest, Right Hon. Sir John, P.C., Swan, Western Australia ... 8,418 13,163 G.C.M.G. -

Mr William Benjamin Chaffey

STATE LIBRARY OF SOUTH AUSTRALIA J. D. SOMERVILLE ORAL HISTORY COLLECTION OH 692/21 Full transcript of an interview with MR WILLIAM BENJAMIN CHAFFEY on 5 March 2003 by Rob Linn Recording available on CD Access for research: Unrestricted Right to photocopy: Copies may be made for research and study Right to quote or publish: Publication only with written permission from the State Library OH 692/21 MR WILLIAM BENJAMIN CHAFFEY NOTES TO THE TRANSCRIPT This transcript was donated to the State Library. It was not created by the J.D. Somerville Oral History Collection and does not necessarily conform to the Somerville Collection's policies for transcription. Readers of this oral history transcript should bear in mind that it is a record of the spoken word and reflects the informal, conversational style that is inherent in such historical sources. The State Library is not responsible for the factual accuracy of the interview, nor for the views expressed therein. As with any historical source, these are for the reader to judge. This transcript had not been proofread prior to donation to the State Library and has not yet been proofread since. Researchers are cautioned not to accept the spelling of proper names and unusual words and can expect to find typographical errors as well. 2 OH 692/21 TAPE 1 - SIDE A AUSTRALIAN WINE ORAL HISTORY PROJECT. Interview with Mr William Benjamin Chaffey on 5th March, 2003. Interviewer: Rob Linn. Well, Mr Chaffey, where and when were you born? BC: I was born in Whittier, California, on November 12th, 1914. -

C:\Documents and Settings\Alan Smithee\My Documents\MOTM

Itkx1//7Lhmdq`knesgdLnmsg9Rshbgshsd Our ongoing search for new minerals to feature finds us scouring the more than forty separate shows that comprise the Tucson Gem & Mineral show every year, looking for large lots of interesting and attractive minerals. The search is rewarded when we make a new contact and find something especially vibrant like this month’s combination of lavender stichtite in green serpentinite! OGXRHB@K OQNODQSHDR Chemistry: Mg6Cr2(CO3)(OH)16A4H2O Basic Hydrous Magnesium Chromium Carbonate (Hydrous Magnesium Chromium Carbonate Hydroxide) Class: Carbonates Subclass: Carbonates with hydroxyl or halogen radicals Group: Hydrotalcite Crystal System: Trigonal Crystal Habits: Crystals rarely macroscopic; usually as crust-like aggregates in matrix; sometimes radiating, micaceous with flexible plates, and nodular with tuberous, irregular surface projections; also massive and fibrous. Color: Lavender, lilac, light violet, pink, or purplish. Luster: Waxy, greasy, sometimes pearly. Transparency: Transparent to translucent Streak: White to pale lilac Refractive Index: 1.516-1.542 Cleavage: Perfect in one direction Fracture: Uneven, brittle. Hardness: 1.5-2.0 Specific Gravity: 2.2 Luminescence: None Distinctive Features and Tests: Softness, color, crystal habits, occurrence in chromium-rich metamorphic environments, and frequent association with serpentinite (a greenish metamorphic rock). Stichtite can be confused with similarly colored sugilite [potassium sodium iron manganese aluminum lithium silicate, KNa2(Fe,Mn,Al)2Li2Si12O30]. -

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} the Peaks of Lyell by Geoffrey Blainey the Peaks of Lyell

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} The Peaks Of Lyell by Geoffrey Blainey The Peaks of Lyell. The Peaks of Lyell is a book by Geoffrey Blainey, originally published in 1954. It contains the history of the Mount Lyell Mining and Railway Company, and through association, Queenstown and further the West Coast Tasmania. It is unique for this type of book in that it has gone to the sixth edition in 2000, and few company histories in Australia have achieved such continual publishing. Blainey was fortunate in being able to speak to older people about the history of the west coast, some who had known Queenstown in its earliest years. The book gives an interesting overview from the materials and people Blainey was able to access in the early 1950s, and the omissions. Due to the nature of a company history, a number of items of Queenstown history did have alternative interpretations on events such as the 1912 North Mount Lyell Disaster, and there were residents of Queenstown living in the town as late as the 1970s who had stories that differed from the official company history. Significant characters from the West Coast Tasmania history such as Robert Carl Sticht and James Crotty amongst a longer list probably still deserve further work on their significance in west coast and tasmanian history, but the book has had significant 'presence' in being in print for so long, new scholarship on some of the neglected topics of west coast history only emerged in the late 1990s. In 1994, when the fifth edition was printed, the Mount Lyell company closed down, and most of the records held by the company were donated to the State Library of Tasmania. -

Malcolm Pearse, 'Australia's Early Managers'

AUSTRALIA’S EARLY MANAGERS Malcolm Pearse1 Macquarie University Abstract The origins of managers and management have been studied comprehensively in Great Britain, Europe and the United States of America, but not in Australia. Most scholars have looked at Australia’s history in the twentieth century to inform the literature on the modern enterprise, big business and management, but the role of the manager or agent was established in many businesses by the 1830s. There were salaried managers in Australia as early as 1799, appointed to oversee farms. The appointment of managers in Australia from as early as 1799 continued the practice of British institutions in some industries. But in other contexts, management practice departed from British practice, demonstrating largely adaptive, rather than repetitive features. As the wool industry dominated the economy, the range of industries grew and managers or agents were appointed to businesses such as public companies, which were formed from at least 1824. During the 1830s, there were managers of theatres, hotels, merchant houses, and in whaling, cattle, sheep, shipping and banking activities. As banking expanded during the 1830s and 1840s, so did the number of managers. Bank managers were appointed both with the entry of new banks and with branch expansion. As banks expanded their branch network, the number of managers increased. The establishment of branches continued another British institution in the colonial context and further reinforced the manager’s role. The rise of the salaried manager in Australia was harnessed to the rise of the public company and began as early as the 1840s but was more evident during the second half of the nineteenth century, when public companies grew bigger and prominent in strategically important industries such as grazing, sugar, water, engineering, electricity, banking, insurance and shipping, river and stage coach transport. -

LORD HOPETOUN Papers, 1853-1904 Reels M936-37, M1154

AUSTRALIAN JOINT COPYING PROJECT LORD HOPETOUN Papers, 1853-1904 Reels M936-37, M1154-56, M1584 Rt. Hon. Marquess of Linlithgow Hopetoun House South Queensferry Lothian Scotland EH30 9SL National Library of Australia State Library of New South Wales Filmed: 1973, 1980, 1983 BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE John Adrian Louis Hope (1860-1908), 7th Earl of Hopetoun (succeeded 1873), 1st Marquess of Linlithgow (created 1902), was born at Hopetoun House, near Edinburgh. He was educated at Eton and the Royal Military College, Sandhurst, but did not enter the Army. In 1883 he was appointed Conservative whip in the House of Lords and in 1885 was made a lord-in-waiting to Queen Victoria. In 1886 he married Hersey Moleyns, the daughter of Lord Ventry. In 1889 Lord Knutsford, the Secretary of State for the Colonies, appointed Hopetoun as Governor of Victoria and he held the post until March 1895. Although it was a time of economic depression, he entertained extravagantly, but his youthful enthusiasm and fondness for horseback tours of country districts won him considerable popularity. His term coincided with the first federation conferences and he supported the federation movement strongly. In 1895-98 Hopetoun was paymaster-general in the government of Lord Salisbury. In 1898 Joseph Chamberlain, the Secretary of State for the Colonies, offered him the post of Governor-General of Canada, but he declined. He was appointed Lord Chamberlain in 1898 and had a close association with members of the Royal Family. In July 1900 Hopetoun was appointed the first Governor-General of the Commonwealth of Australia. He arrived in Sydney on 15 December 1900 and his first task was to appoint the head of the new Commonwealth ministry. -

Mount Lyell Abt Railway Tasmania

Mount Lyell Abt Railway Tasmania Nomination for Engineers Australia Engineering Heritage Recognition Volume 1 Prepared by Ian Cooper FIEAust CPEng (Retired) For Abt Railway Ministerial Corporation & Engineering Heritage Tasmania July 2015 Mount Lyell Abt Railway Engineering Heritage nomination Vol1 TABLE OF CONTENTS VOLUME 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS ii ILLUSTRATIONS iii HERITAGE AWARD NOMINATION FORM iv BASIC DATA FORM v ACCEPTANCE FROM OWNER vi INTRODUCTION 1 OUTLINE HISTORY OF MT LYELL MINING AND RAILWAY Early West Coast mining history 3 Birth of Mt Lyell and the Railway 4 The Intervening ‘Forgotten’ Years (1963-2000) 4 Rebirth of the Abt Railway 5 HISTORICALLY SIGNIFICANT ITEMS The Abt rack system and its creator 6 Survey and construction of the Mt Lyell Abt Railway 7 Restoration of the Railway infrastructure 9 Abt locomotives and the railway operation 11 Restoration of the Abt and diesel locomotives 11 Iron Bridge at Teepookana 12 Renovation of Iron Bridge 13 FURTHER ITEMS OF INTEREST 15 HERITAGE ASSESSMENT Historical significance 16 Historical individuals and associations 16 Creative and technical achievement 17 Research potential 18 Social benefits 18 Rarity 18 Representativeness 18 Integrity/Intactness 19 Statement of Significance 19 Area of Significance 19 INTERPRETATION PLAN 20 REFERENCES 21 VOLUME 2 BIOGRAPHIES PHOTO GALLERY Engineering Heritage Tasmania 2015 Page ii Mount Lyell Abt Railway Engineering Heritage nomination Vol1 ILLUSTRATIONS Volume 1 – Picture Gallery figures Cover Figure - Restored Abt No. 3 locomotive hauling carriages -

Altered States: an Investigation of the Relationship Between Nature And

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 1992 Altered states: an investigation of the relationship between nature and humans in the west country of Tasmania expressed through the ceramic vessel form Vincent McGrath University of Wollongong Recommended Citation McGrath, Vincent, Altered states: an investigation of the relationship between nature and humans in the west country of Tasmania expressed through the ceramic vessel form, Doctor of Creative Arts thesis, School of Creative Arts, University of Wollongong, 1992. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/946 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] ALTERED STATES An investigation of the relationship between nature and humans in the West Country of Tasmania expressed through the ceramic vessel form A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree DOCTOR OF CREATIVE ARTS from UNIVERSITY OF WOLLONGONG by Vincent McGrath M.F.A. (U.P.S., Washington, U.S.A.), F.R.M.I.T. (R.M.I.T.), Dip.A. (R.M.I.T.), S.A.T.C. (Melb.), T.S.T.C. (Melb.) SCHOOL OF CREATIVE ARTS 1992 ii I hereby certify that the work embodied in this dissertation is the result of original research and has not been submitted for a higher degree to any other university or institution. Vincent McGrat TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract IV Acknowledgements v Preface vi Maps vii Introduction A Metaphor