Richard Chaffey Baker and the Shaping Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Political Attitudes to Conscription: 1914–1918

RESEARCH PAPER SERIES, 2016–17 27 OCTOBER 2016 Political attitudes to conscription: 1914–1918 Dr Nathan Church Foreign Affairs, Defence and Security Section Contents Introduction ................................................................................................ 2 Attitudes of the Australian Labor Party ........................................................ 2 Federal government ......................................................................................... 2 New South Wales ............................................................................................. 7 Victoria ............................................................................................................. 8 Queensland ...................................................................................................... 9 Western Australia ........................................................................................... 10 South Australia ............................................................................................... 11 Political impact on the ALP ............................................................................... 11 Attitudes of the Commonwealth Liberal Party ............................................. 12 Attitudes of the Nationalist Party of Australia ............................................. 13 The second conscription plebiscite .................................................................. 14 Conclusion ................................................................................................ -

Biography Sir John Langdon Bonython

Sir John Langdon Bonython (1848-1939) Sir Edward Nicholas Coventry Braddon (1829-1904) Member for South Australia 1901-1903 Member for Tasmania 1901-1903 Member for Barker (South Australia) 1903-1906 Member for Wilmot (Tasmania) 1903-1904 orn in London, England, John Langdon A man well-known for his generosity, dward (Ned) Braddon was born at St Kew, Braddon, a Freetrader, was elected to the BBonython arrived in South Australia in especially towards educational institutions, ECornwall, England, and had a successful House of Representatives for Tasmania in 1854. He joined the Advertiser (Adelaide) Bonython donated large sums of his vast career as a civil servant in India from 1847 1901 at the first federal election, receiving as a reporter in 1864 and became editor fortune to various causes. Bonython sold to 1878. He was involved in many aspects of an impressive 26% of the vote to top the poll. in 1879, a position he held for 45 years. the Advertiser in 1929 for £1 250 000 and colonial administration before migrating to When Tasmania was divided into federal He became sole proprietor of the newspaper upon his death in 1939 his estate was sworn Tasmania in 1878. electoral divisions, he became the member in 1893. Bonython promoted the cause of for probate at over £4 million. He was twice for Wilmot. Braddon died in office in 1904. federation through the Advertiser, but was knighted, first in 1898 for services to the Braddon became involved in Tasmanian vigilant of the rights of smaller states such newspaper industry, and again in 1919 for colonial politics in 1879, was Tasmanian At the age 71 years 9 months Braddon was as South Australia in the federal alliance. -

RACIAL EQUALITY BILL: JAPANESE PROPOSAL at PARIS PEACE CONFERENCE: DIPLOMATIC MANOEUVRES; and REASONS for REJECTION by Shizuka

RACIAL EQUALITY BILL: JAPANESE PROPOSAL AT PARIS PEACE CONFERENCE: DIPLOMATIC MANOEUVRES; AND REASONS FOR REJECTION By Shizuka Imamoto B.A. (Hiroshima Jogakuin University, Japan), Graduate Diploma in Language Teaching (University of Technology Sydney, Australia) A thesis submitted for the degree of Master of Arts (Honours) at Macquarie University. Japanese Studies, Department of Asian Languages, Division of Humanities, College of Humanities and Social Sciences, Macquarie University, Sydney Australia. 2006 DECLARATION I declare that the present research work embodied in the thesis entitled, Racial Equality Bill: Japanese Proposal At Paris Peace Conference: Diplomatic Manoeuvres; And Reasons For Rejection was carried out by the author at Macquarie Japanese Studies Centre of Macquarie University of Sydney, Australia during the period February 2003 to February 2006. This work has not been submitted for a higher degree to any other university or institution. Any published and unpublished materials of other writers and researchers have been given full acknowledgement in the text. Shizuka Imamoto ii TABLE OF CONTENTS DECLARATION ii TABLE OF CONTENTS iii SUMMARY ix DEDICATION x ACKNOWLEDGEMENT xi INTRODUCTION 1 1. Area Of Study 1 2. Theme, Principal Question, And Objective Of Research 5 3. Methodology For Research 5 4. Preview Of The Results Presented In The Thesis 6 End Notes 9 CHAPTER ONE ANGLO-JAPANESE RELATIONS AND WORLD WAR ONE 11 Section One: Anglo-Japanese Alliance 12 1. Role Of Favourable Public Opinion In Britain And Japan 13 2. Background Of Anglo-Japanese Alliance 15 3. Negotiations And Signing Of Anglo-Japanese Alliance 16 4. Second Anglo-Japanese Alliance 17 5. Third Anglo-Japanese Alliance 18 Section Two: Japan’s Involvement In World War One 19 1. -

The River Torrens—Friend and Foe Part 2

The River Torrens—friend and foe Part 2: The river as an obstacle to be crossed RICHARD VENUS Richard Venus BTech, BA, GradCertArchaeol, MIE Aust is a retired electrical engineer who now pursues his interest in forensic heritology, researching and writing about South Australia’s engineering heritage. He is Chairman of Engineering Heritage South Australia and Vice President of the History Council of South Australia. His email is [email protected] Beginnings In Part 1 we looked the River Torrens as a friend—a source of water vital to the establishment of the new settlement. However, in common with so many other European settlements, the developing community very quickly polluted its own water supply and another source had to be found. This was still the River Torrens but the water was collected in the Torrens Gorge, about 13 kilometres north-east of the City, and piped down Payneham Road to the Valve House in the East Parklands. Water from this source was first made available in December 1860 as reported in the South Australian Advertiser on 26 December. The significant challenge presented by the Torrens was getting across it. In summer, when the river was little more than a series of pools, you could just walk across. However, there must have been a significant body of water somewhere – probably in the vicinity of today’s weir – because in July 1838 tenders were called ‘For the rent for six months of the small punt on the Torrens for foot passengers, for each of whom a toll of one penny will be authorised to be charged from day-light to dark, and two pence after dark’ (Register 28 July). -

JHSSA Index 2014

Journal of the Historical Society of South Australia Subject Index 1975-2014 Nos 1 to 42 Compiled by Brian Samuels The Historical Society of South Australia Inc PO Box 519 Kent Town 5071 South Australia JHSSA Subject Index 1975–2014 page 35 Subject Index 1975-2014: Nos 1 to 42 This index consolidates and updates the Subject Index to the Journal of the Historical Society of South Australia Nos 1 - 20 (1974 [sic] - 1992) which appeared in the 1993 Journal and its successors for Nos 21 - 25 (1998 Journal) and 26 - 30 (2003 Journal). In the latter index new headings for Gardens, Forestry, Place Names and Utilities were added and some associated reindexing of the entire index database was therefore undertaken. The indexing of a few other entries was also improved, as has occurred with this latest updating, in which Heritage Conservation and Imperial Relations are new headings while Death Rituals has been subsumed into Folklife. The index has certain limitations of design. It uses a limited number of, and in many instances relatively broad, subject headings. It indexes only the main subjects of each article, judged primarily from the title, and does not index the contents – although Biography and Places have subheadings. Authors and titles are not separately indexed, but they do comprise separate fields in the index database. Hence author and title indexes could be included in future published indexes if required. Titles are cited as they appear at the head of each article. Occasionally a note in square brackets has been added to clarify or amplify a title. -

FSMA HOUSE, 52-56 Gawler Place ZONE/POLICY AREA: CBA - PA14 Former Claridge House

City of Adelaide Heritage Survey (2008) NAME: FSMA HOUSE, 52-56 Gawler Place ZONE/POLICY AREA: CBA - PA14 Former Claridge House APPROVED / CURRENT USE: Offices / Shop FORMER USE: Commercial DATE(S) OF CONSTRUCTION: 1926–1927 LOCATION: 52-56 Gawler Place ADELAIDE SA 5000 LOCAL GOVERNMENT AREA: Adelaide City Council LAND DESCRIPTION: CT-5556/385 HERITAGE STATUS: Local Heritage Place OTHER ASSESSMENTS Donovan, Marsden & Stark, 1982; McDougall & Vines, 1993 FSMA House (Former Claridge House), 52-54 Gawler Place—View to southeast NAME: FSMA HOUSE, 52-56 Gawler Place ZONE/POLICY AREA: CBA - PA14 Former Claridge House DESCRIPTION: Six-storey Inter-War Classical Revival commercial building constructed to Gawler Place alignment and extending through to Francis Street at rear. Built on a medium sized city allotment, the reinforced concrete rendered building has strong vertical façade surmounted by projecting cornice with brackets and central protruding bay with elaborate pediment treatment with brackets beneath the cornice and recessed balcony on fifth floor. Façade articulated by metal panels to window widths and metal framed windows. Strongly coursed vertical pilasters which vertically divide façade. Cantilevered awning. Major alterations at ground floor level. Francis Street façade of unadorned render. Basement windows evident. The assessment includes the whole of the building, with particular attention to the detailing of the western elevation: it also includes an appropriate relationship between interior floors and external features such as windows and doors. The assessment does not include detailing to southern eastern and northern elevations, alterations to the ground floor shopfront, the cantilevered verandah, nor interiors. STATEMENT OF HERITAGE VALUE: The building is of heritage value as a prominent work of architect Philip Claridge with its fine detailing in Classical Revival style, because it retains original fabric and for the manner in which it reflects the changed nature of commercial activity in Gawler Place. -

The Making of White Australia

The making of White Australia: Ruling class agendas, 1876-1888 Philip Gavin Griffiths A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The Australian National University December 2006 I declare that the material contained in this thesis is entirely my own work, except where due and accurate acknowledgement of another source has been made. Philip Gavin Griffiths Page v Contents Acknowledgements ix Abbreviations xiii Abstract xv Chapter 1 Introduction 1 A review of the literature 4 A ruling class policy? 27 Methodology 35 Summary of thesis argument 41 Organisation of the thesis 47 A note on words and comparisons 50 Chapter 2 Class analysis and colonial Australia 53 Marxism and class analysis 54 An Australian ruling class? 61 Challenges to Marxism 76 A Marxist theory of racism 87 Chapter 3 Chinese people as a strategic threat 97 Gold as a lever for colonisation 105 The Queensland anti-Chinese laws of 1876-77 110 The ‘dangers’ of a relatively unsettled colonial settler state 126 The Queensland ruling class galvanised behind restrictive legislation 131 Conclusion 135 Page vi Chapter 4 The spectre of slavery, or, who will do ‘our’ work in the tropics? 137 The political economy of anti-slavery 142 Indentured labour: The new slavery? 149 The controversy over Pacific Islander ‘slavery’ 152 A racially-divided working class: The real spectre of slavery 166 Chinese people as carriers of slavery 171 The ruling class dilemma: Who will do ‘our’ work in the tropics? 176 A divided continent? Parkes proposes to unite the south 183 Conclusion -

Yet We Are Told That Australians Do Not Sympathise with Ireland’

UNIVERSITY OF ADELAIDE ‘Yet we are told that Australians do not sympathise with Ireland’ A study of South Australian support for Irish Home Rule, 1883 to 1912 Fidelma E. M. Breen This thesis was submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Philosophy by Research in the Faculty of Humanities & Social Sciences, University of Adelaide. September 2013. 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES .......................................................................................................... 3 LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS .............................................................................................. 3 LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS .............................................................................................. 4 Declaration ........................................................................................................... 5 Acknowledgements .............................................................................................. 6 ABSTRACT ........................................................................................................................ 7 CHAPTER 1 ........................................................................................................................ 9 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................... 9 WHAT WAS THE HOME RULE MOVEMENT? ................................................................. 17 REVIEW OF THE LITERATURE .................................................................................... -

SIR WILLIAM JERVOIS Papers, 1877-78 Reel M1185

AUSTRALIAN JOINT COPYING PROJECT SIR WILLIAM JERVOIS Papers, 1877-78 Reel M1185 Mr John Jervois Lloyd’s Lime Street London EC3M 7HL National Library of Australia State Library of New South Wales Filmed: 1981 BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE Sir William Francis Drummond Jervois (1821-1897) was born at Cowes on the Isle of Wight and educated at Dr Burney’s Academy near Gosport and the Royal Military Academy at Woolwich. He was commissioned as a lieutenant in the Royal Engineers in 1839. He was posted to the Cape of Good Hope in 1841, where he began the first survey of British Kaffirland. He subsequently held a number of posts, including commanding royal engineer for the London district (1855-56), assistant inspector-general of fortifications at the War Office (1856-62) and secretary to the defence committee (1859-75). He was made a colonel in 1867 and knighted in 1874. In 1875 Jervois was sent to Singapore as governor of the Straits Settlements. He antagonised the Colonial Office by pursuing an interventionist policy in the Malayan mainland, crushing a revolt in Perak with troops brought from India and Hong Kong. He was ordered to back down and the annexation of Perak was forbidden. He compiled a report on the defences of Singapore. In 1877, accompanied by Lieutenant-Colonel Peter Scratchley, Jervois carried out a survey of the defences of Australia and New Zealand. In the same year he was promoted major-general and appointed governor of South Australia. He immediately faced a political crisis, following the resignation of the Colton Ministry. There was pressure on Jervois to dissolve Parliament, but he appointed James Boucaut as premier and there were no further troubles. -

Michael” to “Myrick”

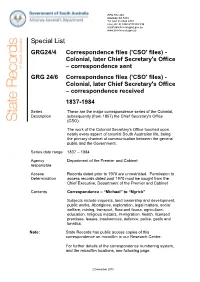

GPO Box 464 Adelaide SA 5001 Tel (+61 8) 8204 8791 Fax (+61 8) 8260 6133 DX:336 [email protected] www.archives.sa.gov.au Special List GRG24/4 Correspondence files ('CSO' files) - Colonial, later Chief Secretary's Office – correspondence sent GRG 24/6 Correspondence files ('CSO' files) - Colonial, later Chief Secretary's Office – correspondence received 1837-1984 Series These are the major correspondence series of the Colonial, Description subsequently (from 1857) the Chief Secretary's Office (CSO). The work of the Colonial Secretary's Office touched upon nearly every aspect of colonial South Australian life, being the primary channel of communication between the general public and the Government. Series date range 1837 – 1984 Agency Department of the Premier and Cabinet responsible Access Records dated prior to 1970 are unrestricted. Permission to Determination access records dated post 1970 must be sought from the Chief Executive, Department of the Premier and Cabinet Contents Correspondence – “Michael” to “Myrick” Subjects include inquests, land ownership and development, public works, Aborigines, exploration, legal matters, social welfare, mining, transport, flora and fauna, agriculture, education, religious matters, immigration, health, licensed premises, leases, insolvencies, defence, police, gaols and lunatics. Note: State Records has public access copies of this correspondence on microfilm in our Research Centre. For further details of the correspondence numbering system, and the microfilm locations, see following page. 2 December 2015 GRG 24/4 (1837-1856) AND GRG 24/6 (1842-1856) Index to Correspondence of the Colonial Secretary's Office, including some newsp~per references HOW TO USE THIS SOURCE References Beginning with an 'A' For example: A (1849) 1159, 1458 These are letters to the Colonial Secretary (GRG 24/6) The part of the reference in brackets is the year ie. -

Thrf-2019-1-Winners-V3.Pdf

TO ALL 21,100 Congratulations WINNERS Home Lottery #M13575 JohnDion Bilske Smith (#888888) JohnGeoff SmithDawes (#888888) You’ve(#105858) won a 2019 You’ve(#018199) won a 2019 BMWYou’ve X4 won a 2019 BMW X4 BMWYou’ve X4 won a 2019 BMW X4 KymJohn Tuck Smith (#121988) (#888888) JohnGraham Smith Harrison (#888888) JohnSheree Smith Horton (#888888) You’ve won the Grand Prize Home You’ve(#133706) won a 2019 You’ve(#044489) won a 2019 in Brighton and $1 Million Cash BMWYou’ve X4 won a 2019 BMW X4 BMWYou’ve X4 won a 2019 BMW X4 GaryJohn PeacockSmith (#888888) (#119766) JohnBethany Smith Overall (#888888) JohnChristopher Smith (#888888)Rehn You’ve won a 2019 Porsche Cayenne, You’ve(#110522) won a 2019 You’ve(#132843) won a 2019 trip for 2 to Bora Bora and $250,000 Cash! BMWYou’ve X4 won a 2019 BMW X4 BMWYou’ve X4 won a 2019 BMW X4 Holiday for Life #M13577 Cash Calendar #M13576 Richard Newson Simon Armstrong (#391397) Win(#556520) a You’ve won $200,000 in the Cash Calendar You’ve won 25 years of TICKETS Win big TICKETS holidayHolidays or $300,000 Cash STILL in$15,000 our in the Cash Cash Calendar 453321 Annette Papadulis; Dernancourt STILL every year AVAILABLE 383643 David Allan; Woodville Park 378834 Tania Seal; Wudinna AVAILABLE Calendar!373433 Graeme Blyth; Para Hills 428470 Vipul Sharma; Mawson Lakes for 25 years! 361598 Dianne Briske; Modbury Heights 307307 Peter Siatis; North Plympton 449940 Kate Brown; Hampton 409669 Victor Sigre; Henley Beach South 371447 Darryn Burdett; Hindmarsh Valley 414915 Cooper Stewart; Woodcroft 375191 Lynette Burrows; Glenelg North 450101 Filomena Tibaldi; Marden 398275 Stuart Davis; Hallett Cove 312911 Gaynor Trezona; Hallett Cove 418836 Deidre Mason; Noarlunga South 321163 Steven Vacca; Campbelltown 25 years of Holidays or $300,000 Cash $200,000 in the Cash Calendar Winner to be announced 29th March 2019 Winners to be announced 29th March 2019 Finding cures and improving care Date of Issue Home Lottery Licence #M13575 2729 FebruaryMarch 2019 2019 Cash Calendar Licence ##M13576M13576 in South Australia’s Hospitals. -

SENATE Official Hansard

COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES SENATE Official Hansard WEDNESDAY, 16 OCTOBER 1996 THIRTY-EIGHTH PARLIAMENT FIRST SESSION—FIRST PERIOD BY AUTHORITY OF THE SENATE CANBERRA CONTENTS WEDNESDAY, 16 OCTOBER Petitions— Telstra: Privatisation ................................... 4207 Radio Triple J ....................................... 4207 Australian Broadcasting Corporation ........................ 4207 Ramsar Treaty ....................................... 4207 Commonwealth Dental Health Program ...................... 4207 Notices of Motion— DIFF Scheme ........................................ 4207 Sessional Orders ...................................... 4208 DIFF Scheme ........................................ 4208 Days and Hours of Meeting .............................. 4208 Doctors ............................................ 4208 Privacy .............................................. 4209 Order of Business— First Speech ......................................... 4209 Rural and Regional Affairs and Transport References Committee .... 4209 Live Sheep Trade ..................................... 4209 Parliamentary Elections ................................. 4209 Visit by US Nuclear Warship ............................ 4209 Social Security Legislation Amendment (Further Budget and Other Measures) Bill 1996— First Reading ........................................ 4210 Second Reading ...................................... 4210 East Timor ........................................... 4211 Joshua Slocum .......................................