Populism in Contemporary Pakistan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

General Election 2018 Update-Ii - Fafen General Election 2018

GENERAL ELECTION 2018 UPDATE-II - FAFEN GENERAL ELECTION 2018 Update-II April 01 – April 30, 2018 1. BACKGROUND AND INTRODUCTION Free and Fair Election Network (FAFEN) initiated its assessment of the political environment and implementation of election-related laws, rules and regulations in January 2018 as part of its multi-phase observation of General Election (GE) 2018. The purpose of the observation is to contribute to the evolution of an election process that is free, fair, transparent and accountable, in accordance with the requirements laid out in the Elections Act, 2017. Based on its observation, FAFEN produces periodic updates, information briefs and reports in an effort to provide objective, unbiased and evidence-based information about the quality of electoral and political processes to the Election Commission of Pakistan (ECP), political parties, media, civil society organizations and citizens. General Election 2018 Update-II is based on information gathered systematically in 130 districts by as many trained and non-partisan District Coordinators (DCs) through 560 interviews1 with representatives of 33 political parties and groups and 294 interviews with representative of 35 political parties and groups over delimitation process. The Update also includes the findings of observation of 559 political gatherings and 474 ECP’s centres set up for the display of preliminary electoral rolls. FAFEN also documented the formation of 99 political alliances, party-switching by political figures, and emerging alliances among ethnic, tribal and professional groups. In addition, the General Election 2018 Update-II comprises data gathered through systematic monitoring of 86 editions of 25 local, regional and national newspapers to report incidents of political and electoral violence, new development schemes and political advertisements during April 2018. -

Additional Documents to the Amicus Brief Submitted to the Jerusalem District Court

בבית המשפט המחוזי בירושלים עת"מ 36759-05-18 בשבתו כבית משפט לעניינים מנהליים בעניין שבין: 1( ארגון Human Rights Watch 2( עומר שאקר העותרים באמצעות עו"ד מיכאל ספרד ו/או אמילי שפר עומר-מן ו/או סופיה ברודסקי מרח' דוד חכמי 12, תל אביב 6777812 טל: 03-6206947/8/9, פקס 03-6206950 - נ ג ד - שר הפנים המשיב באמצעות ב"כ, מפרקליטות מחוז ירושלים, רחוב מח"ל 7, מעלות דפנה, ירושלים ת.ד. 49333 ירושלים 9149301 טל: 02-5419555, פקס: 026468053 המכון לחקר ארגונים לא ממשלתיים )עמותה רשומה 58-0465508( ידיד בית המשפט באמצעות ב"כ עו"ד מוריס הירש מרח' יד חרוצים 10, ירושלים טל: 02-566-1020 פקס: 077-511-7030 השלמת מסמכים מטעם ידיד בית המשפט בהמשך לדיון שהתקיים ביום 11 במרץ 2019, ובהתאם להחלטת כב' בית המשפט, מתכבד ידיד בית המשפט להגיש את ריכוז הציוציו של העותר מס' 2 החל מיום 25 ליוני 2018 ועד ליום 10 למרץ 2019. כפי שניתן להבחין בנקל מהתמצית המצ"ב כנספח 1, בתקופה האמורה, אל אף טענתו שהינו "פעיל זכויות אדם", בפועל ציוציו )וציוציו מחדש Retweets( התמקדו בנושאים שבהם הביע תמיכה בתנועת החרם או ביקורת כלפי מדינת ישראל ומדיניותה, אך נמנע, כמעט לחלוטין, מלגנות פגיעות בזכיות אדם של אזרחי מדינת ישראל, ובכלל זה, גינוי כלשהו ביחס למעשי רצח של אזרחים ישראלים בידי רוצחים פלסטינים. באשר לטענתו של העותר מס' 2 שחשבון הטוויטר שלו הינו, בפועל, חשבון של העותר מס' 1, הרי שגם כאן ניתן להבין בנקל שטענה זו חסרת בסיס כלשהי. ראשית, החשבון מפנה לתפקידו הקודם בארגון CCR, אליו התייחסנו בחוות הדעת המקורית מטעם ידיד בית המשפט בסעיף 51. -

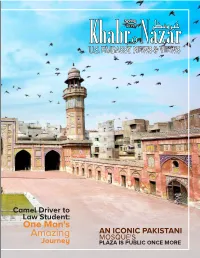

KON 4Th Edition Spring 2019

Spring Camel Driver to Law Student: One Man's AN ICONIC PAKISTANI Amazing MOSQUE'S Journey PLAZA IS PUBLIC ONCE MORE SPRING EDITION Editor in Chief Christopher Fitzgerald – Minister Counselor for Public Affairs Managing Editor Richard Snelsire – Embassy Spokesperson Associate Editor Donald Cordell, Wasim Abbas Background Khabr-o-Nazar is a free magazine published by U.S. Embassy, Islamabad Stay Connected Khabr-o-Nazar, Public Affairs Section U.S. Embassy, Ramna 5, Diplomatic Enclave Islamabad, Pakistan Email [email protected] Website http://pk.usembassy.gov/education.culture/khabr_o_nazar.html Magazine is designed & printed by GROOVE ASSOCIATES Telephone: 051-2620098 Mobile: 0345-5237081 flicker.com/photos www.youtube.com/- @usembislamabad www.facebook.com/ www.twitter.com/use- /usembpak c/usembpak pakistan.usembassy mbislamabad CCoonnttenentt 04 EVENTS 'Top Chef' Contestant Fatima Ali 06 on How Cancer Changed A CHAT WITH the Way She Cooks ACTING DEPUTY ASSISTANT SECRETARY 08 HENRY ENSHER A New Mission Through a unique summer camp iniave, Islamabad's police forge bonds with their communies — one family at a me 10 Cities of the Sun Meet Babcock Ranch, a groundbreaking model 12 for sustainable communies of the future. Young Pakistani Scholars Preparing to Tackle Pakistan's 14 Energy Crisis Camel Driver to Law Student: One Man's 16 Amazing Journey Consular Corner Are you engaged to or dang a U.S. cizen? 18 An Iconic Pakistani Mosque’s Plaza 19 Is Public Once More From February 25 to March 8, English Language Specialist Dr. Loe Baker, conducted a series of professional development workshops for English teachers from universies across the country. -

Walking the Talk: 2021 Blueprints for a Human Rights-Centered U.S

Walking the Talk: 2021 Blueprints for a Human Rights-Centered U.S. Foreign Policy October 2020 Acknowledgments Human Rights First is a nonprofit, nonpartisan human rights advocacy and action organization based in Washington D.C., New York, and Los Angeles. © 2020 Human Rights First. All Rights Reserved. Walking the Talk: 2021 Blueprints for a Human Rights-Centered U.S. Foreign Policy was authored by Human Rights First’s staff and consultants. Senior Vice President for Policy Rob Berschinski served as lead author and editor-in-chief, assisted by Tolan Foreign Policy Legal Fellow Reece Pelley and intern Anna Van Niekerk. Contributing authors include: Eleanor Acer Scott Johnston Trevor Sutton Rob Berschinski David Mizner Raha Wala Cole Blum Reece Pelley Benjamin Haas Rita Siemion Significant assistance was provided by: Chris Anders Steven Feldstein Stephen Pomper Abigail Bellows Becky Gendelman Jennifer Quigley Brittany Benowitz Ryan Kaminski Scott Roehm Jim Bernfield Colleen Kelly Hina Shamsi Heather Brandon-Smith Kate Kizer Annie Shiel Christen Broecker Kennji Kizuka Mandy Smithberger Felice Gaer Dan Mahanty Sophia Swanson Bishop Garrison Kate Martin Yasmine Taeb Clark Gascoigne Jenny McAvoy Bailey Ulbricht Liza Goitein Sharon McBride Anna Van Niekerk Shannon Green Ian Moss Human Rights First challenges the United States of America to live up to its ideals. We believe American leadership is essential in the struggle for human dignity and the rule of law, and so we focus our advocacy on the U.S. government and other key actors able to leverage U.S. influence. When the U.S. government falters in its commitment to promote and protect human rights, we step in to demand reform, accountability, and justice. -

Government of Pakistan Ministry of Federal Education & Professional

Government of Pakistan Ministry of Federal Education & Professional Training ********* INTRODUCTION: • In the wake of 18th Amendment to the Constitution the concurrent list stands abolished. Subjects of Education and Health etc. no longer remain in the purview of the Federal Government. Therefore, the Ministries of Education, Health and fifteen other ministries were devolved from 5th April, 2011 to 30th June, 2011. • Entry-16 of Part 1 of Federal Legislative list reads as follows: “Federal Agencies and Institutes for the following purposes that is to say, for research, for professional and technical training, or for the promotion of special studies” will be organized by the Federal Government. • Therefore, the Federal Agencies and Institutes imparting professional and technical training and research have been retained by the Federal Government. • To cater for the educational, professional and technical training requirements of the country after devolution, the Government has taken a very timely decision by creating a dedicated Ministry for the purpose. • The Ministry of Professional & Technical Training was notified on 29th July, 2011. Later on, the Ministry has been re-named as Ministry of Education, Trainings and Standards in Higher Education. Finally, on the recommendations of CCI the Ministry has now been renamed as Ministry Federal Education & Professional Training. Presently following departments/organizations are working under administrative control of the Ministry of Federal Education & Professional Training:- S.No. Name of Departments/Organizations 1. Higher Education Commission (HEC) 2. National Vocational & Technical Education Commission (NAVTEC) 3. National Commission for Human Development (NCHD) 4. Federal Board of Intermediate and Secondary Education (FBISE) 5. National Education Foundation (NEF) 6. -

Articles Al-Qaida and the Pakistani Harakat Movement: Reflections and Questions About the Pre-2001 Period by Don Rassler

PERSPECTIVES ON TERRORISM Volume 11, Issue 6 Articles Al-Qaida and the Pakistani Harakat Movement: Reflections and Questions about the pre-2001 Period by Don Rassler Abstract There has been a modest amount of progress made over the last two decades in piecing together the developments that led to creation of al-Qaida and how the group has evolved over the last 30 years. Yet, there are still many dimensions of al-Qaida that remain understudied, and likely as a result, poorly understood. One major gap are the dynamics and relationships that have underpinned al-Qaida’s multi-decade presence in Pakistan. The lack of developed and foundational work done on the al-Qaida-Pakistan linkage is quite surprising given how long al- Qaida has been active in the country, the mix of geographic areas - from Pakistan’s tribal areas to its main cities - in which it has operated and found shelter, and the key roles Pakistani al-Qaida operatives have played in the group over the last two decades. To push the ball forward and advance understanding of this critical issue, this article examines what is known, and has been suggested, about al-Qaida’s relations with a cluster of Deobandi militant groups consisting of Harakat ul-Mujahidin, Harakat ul-Jihad Islami, Harakat ul-Ansar, and Jaish-e-Muhammad, which have been collectively described as Pakistan’s Harakat movement, prior to 9/11. It finds that each of these groups and their leaders provided key elements of support to al-Qaida in a number of direct and indirect ways. -

1396 the Platforms of Our Discontent (Social Media, Social Destruction)

#1396 The Pla-orms of Our Discontent (Social Media, Social Destruc?on) JAY TOMLINSON - HOST, BEST OF THE LEFT: [00:00:00] Welcome to this episode of the award-winning Best of the Le; Podcast in which we shall learn about the role that social media plays in the radicalizaAon of discontented communiAes, and engage in the debate over content moderaAon and de-plaDorming of individuals. Clips today are from The Weeds, Newsbroke from AJ Plus, On the Media, Off-Kilter, a piece of a speech from Sasha Baron Cohen, Big Tech, Vox ConversaAons, the Medhi Hasan Show, and Your Undivided AVenAon. Why everyone hates Big Tech, with The Verge's Nilay Patel - The Weeds - Air Date 7-19-19 NILAY PATEL: [00:00:34] I think one thing everyone will agree on, just universally, is that these companies are not necessarily well-run. And even if they were perfectly run, the nature of wriAng and enforcing speech regulaAon is such that you're sAll gonna do a bad job. The United States has been trying to develop a free speech policy in our courts for 220+ years and we're preVy bad at it, but four guys at Facebook aren't going to do a good job up in 20 years. So there's that problem, where does the line cross from being a preVy funny joke to being overtly bigoted? It really depends on context. We all understand this. So it absolutely depends on the context. It depends on who you think you are speaking to, whether it's a group of your friends or whether suddenly TwiVer's algorithm grabs you and amplifies you to millions of people. -

Osama Bin Laden Shot Dead by Navy Seals 9 Years Ago Today

We Are Vets We-Are-Vets.us Osama bin Laden Shot Dead by Navy SEALs 9 Years Ago Today Osama bin Laden sits with his adviser Dr. Ayman al-Zawahiri during an interview with Pakistani journalist Hamid Mir. Hamid Mir took this picture during his third and last interview with Osama bin Laden in November 2001 in Kabul. Nine years ago today, on May 1, 2011, Osama bin Laden was shot and killed in Islamabad, Pakistan after U.S. Navy SEALs from SEAL Team Six conducted a raid on his compound in Operation Neptune Spear. I remember watching the celebrations in Times Square, NYC and Washington, DC with great pride after hearing that our military upheld the promise to hold the man responsible for 9/11 accountable. Never thought I’d be able to thank The Operator in person. Rob O’Neill, the Navy SEAL who says he was the one who fired the shots that killed bin Laden during the raid on his Abbottabad compound, has posted to Twitter in the past about the anniversary. He also appeared on Fox & Friends in 2018 to speak about that day. “How did a kid from Montana who would barely swim become a Navy SEAL and end up right here at this moment,” O’Neill said, recalling watching announcements of bin Laden’s death on TV while the terrorist leader’s dead body was at his feet.” “It was such an awesome night,” he continued. “It was such an honor to be a part of that incredible team.” O’Neill described some of the events of that night, including the moment he came face-to- face with bin Laden. -

MAPPING DIGITAL MEDIA: PAKISTAN Mapping Digital Media: Pakistan

COUNTRY REPORT MAPPING DIGITAL MEDIA: PAKISTAN Mapping Digital Media: Pakistan A REPORT BY THE OPEN SOCIETY FOUNDATIONS WRITTEN BY Huma Yusuf 1 EDITED BY Marius Dragomir and Mark Thompson (Open Society Media Program editors) Graham Watts (regional editor) EDITORIAL COMMISSION Yuen-Ying Chan, Christian S. Nissen, Dusˇan Reljic´, Russell Southwood, Michael Starks, Damian Tambini The Editorial Commission is an advisory body. Its members are not responsible for the information or assessments contained in the Mapping Digital Media texts OPEN SOCIETY MEDIA PROGRAM TEAM Meijinder Kaur, program assistant; Morris Lipson, senior legal advisor; and Gordana Jankovic, director OPEN SOCIETY INFORMATION PROGRAM TEAM Vera Franz, senior program manager; Darius Cuplinskas, director 21 June 2013 1. Th e author thanks Jahanzaib Haque and Individualland Pakistan for their help with researching this report. Contents Mapping Digital Media ..................................................................................................................... 4 Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................... 6 Context ............................................................................................................................................. 10 Social Indicators ................................................................................................................................ 12 Economic Indicators ........................................................................................................................ -

Ofcom, PEMRA and Mighty Media Conglomerates

Ofcom, PEMRA and Mighty Media Conglomerates Syeda Amna Sohail Ofcom, PEMRA and Mighty Media Conglomerates THESIS To obtain the degree of Master of European Studies track Policy and Governance from the University of Twente, the Netherlands by Syeda Amna Sohail s1018566 Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Robert Hoppe Referent: Irna van der Molen Contents 1 Introduction 4 1.1 Motivation to do the research . 5 1.2 Political and social relevance of the topic . 7 1.3 Scientific and theoretical relevance of the topic . 9 1.4 Research question . 10 1.5 Hypothesis . 11 1.6 Plan of action . 11 1.7 Research design and methodology . 11 1.8 Thesis outline . 12 2 Theoretical Framework 13 2.1 Introduction . 13 2.2 Jakubowicz, 1998 [51] . 14 2.2.1 Communication values and corresponding media system (minutely al- tered Denis McQuail model [60]) . 14 2.2.2 Different theories of civil society and media transformation projects in Central and Eastern European countries (adapted by Sparks [77]) . 16 2.2.3 Level of autonomy depends upon the combination, the selection proce- dure and the powers of media regulatory authorities (Jakubowicz [51]) . 20 2.3 Cuilenburg and McQuail, 2003 . 21 2.4 Historical description . 23 2.4.1 Phase I: Emerging communication policy (till Second World War for modern western European countries) . 23 2.4.2 Phase II: Public service media policy . 24 2.4.3 Phase III: New communication policy paradigm (1980s/90s - till 2003) 25 2.4.4 PK Communication policy . 27 3 Operationalization (OFCOM: Office of Communication, UK) 30 3.1 Introduction . -

Pakistan, Country Information

Pakistan, Country Information PAKISTAN ASSESSMENT April 2003 Country Information and Policy Unit I SCOPE OF DOCUMENT II GEOGRAPHY III ECONOMY IV HISTORY V STATE STRUCTURES VI HUMAN RIGHTS VIA. HUMAN RIGHTS ISSUES VIB. HUMAN RIGHTS - SPECIFIC GROUPS VIC. HUMAN RIGHTS - OTHER ISSUES ANNEX A: CHRONOLOGY OF MAJOR EVENTS ANNEX B: POLITICAL ORGANISATIONS AND OTHER GROUPS ANNEX C: PROMINENT PEOPLE ANNEX D: REFERENCES TO SOURCE MATERIAL 1. SCOPE OF DOCUMENT 1.1 This assessment has been produced by the Country Information and Policy Unit, Immigration and Nationality Directorate, Home Office, from information obtained from a wide variety of recognised sources. The document does not contain any Home Office opinion or policy. 1.2 The assessment has been prepared for background purposes for those involved in the asylum / human rights determination process. The information it contains is not exhaustive. It concentrates on the issues most commonly raised in asylum / human rights claims made in the United Kingdom. 1.3 The assessment is sourced throughout. It is intended to be used by caseworkers as a signpost to the source material, which has been made available to them. The vast majority of the source material is readily available in the public domain. These sources have been checked for currency, and as far as can be ascertained, remained relevant and up to date at the time the document was issued. 1.4 It is intended to revise the assessment on a six-monthly basis while the country remains within the top 35 asylum-seeker producing countries in the United Kingdom. 2. GEOGRAPHY file:///V|/vll/country/uk_cntry_assess/apr2003/0403_Pakistan.htm[10/21/2014 9:56:32 AM] Pakistan, Country Information General 2.1 The Islamic Republic of Pakistan lies in southern Asia, bordered by India to the east and Afghanistan and Iran to the west. -

Gallup TV Ratings Services – the Only National TV Ratings Service

Gallup TV Ratings Services – The Only National TV Ratings Service Star Plus is Pakistan's Most watched Channel among Cable & Satellite Viewers : Gallup TV Ratings Service Dear Readers, Greetings! Gallup TV Ratings Service (the only National TV Ratings Service) released a report on most popular TV Channels in Pakistan. The report is compiled on the basis of the Gallup TV Ratings Services, the only National TV Ratings available for Pakistan. According to the report, Star Plus tops the list and had an average daily reach of around 12 million Cable and Satellite Viewers during the time period Jan- to date (2013). Second in line are PTV Home and Geo News with approximately 8 million average daily Cable and Satellite Viewers. The channel list below provides list of other channels who come in the top 20 channels list. Please note that the figures released are not counting the viewership of Terrestrial TV Viewers. These terrestrial TV viewers still occupy a majority of TV viewers in the country. Data Source: Gallup Pakistan Top 20 channels in terms of viewership in 2013 Target Audience: Cable & Satellite Viewers Period: Jan-Jun , 2013 Function: Daily Average Reach (in % and thousands Viewers) Rank Channel Name Avg Reach % Avg Reach '000 1 Star Plus 17.645 12,507 2 GEO News 11.434 8,105 3 PTV Home 10.544 7,474 4 Sony 8.925 6,327 5 Cartoon Network 8.543 6,055 6 GEO Entertainment 7.376 5,228 7 ARY Digital 5.078 3,599 8 KTN 5 3,544 9 PTV News 4.825 3,420 10 Urdu 1 4.233 3,000 11 Hum TV 4.19 2,970 12 ATV 3.898 2,763 13 Express News 2.972 2,107 14 ARY News 2.881 2,042 15 Ten Sports 2.861 2,028 16 Sindh TV 2.446 1,734 17 PTV Sports 2.213 1,568 18 ARY Qtv 2.019 1,431 19 Samaa TV 1.906 1,351 20 A Plus 1.889 1,339 Gallup Pakistan's TV Ratings service is based on a panel of over 5000 Households Spread across both Urban and Rural areas of Pakistan (covering all four provinces).