Theory and Practice in Language Studies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Contrastive Study of the Ibibio and Igbo Sound Systems

A CONTRASTIVE STUDY OF THE IBIBIO AND IGBO SOUND SYSTEMS GOD’SPOWER ETIM Department Of Languages And Communication Abia State Polytechnic P.M.B. 7166, Aba, Abia State, Nigeria. [email protected] ABSTRACT This research strives to contrast the consonant phonemes, vowel phonemes and tones of Ibibio and Igbo in order to describe their similarities and differences. The researcher adopted the descriptive method, and relevant data on the phonology of the two languages were gathered and analyzed within the framework of CA before making predictions and conclusions. Ibibio consists of ten vowels and fourteen consonant phonemes, while Igbo is made up of eight vowels and twenty-eight consonants. The results of contrastive analysis of the two languages showed that there are similarities as well as differences in the sound systems of the languages. There are some sounds in Ibibio which are not present in Igbo. Also many sounds are in Igbo which do not exist in Ibibio. Both languages share the phonemes /e, a, i, o, ɔ, u, p, b, t, d, k, kp, m, n, ɲ, j, ŋ, f, s, j, w/. All the phonemes in Ibibio are present in Igbo except /ɨ/, /ʉ/, and /ʌ/. Igbo has two vowel segments /ɪ/ and /ʊ/ and also fourteen consonant phonemes /g, gb, kw, gw, ŋw, v, z, ʃ, h, ɣ, ʧ, ʤ, l, r/ which Ibibio lacks. Both languages have high, low and downstepped tones but Ibibio further has contour or gliding tones which are not tone types in Igbo. Also, the downstepped tone in Ibibio is conventionally marked with exclamation point, while in Igbo, it is conventionally marked with a raised macron over the segments bearing it. -

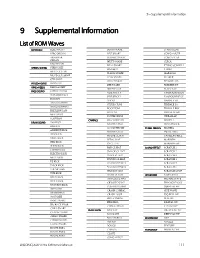

ASR-X Pro 3.00

9ÑSupplemental Information 9 Suppll ementttall II nffformatttii on Lii sttt offf ROM Waves KEYBOARD ELEC PIANO JAMM SNARE CONGA LOW PERC ORGAN LIVE SNARE CONGA MUTE DRAWBAR LUDWIG SNARE CONGA SLAP ORGAN MUTT SNARE CUICA PAD SYNTH REAL SNARE ETHNO COWBELL STRII NG-SOUND STRING HIT RIMSHOT GUIRO MUTE GUITAR SLANG SNARE MARACAS MUTE GUITARWF SPAK SNARE SHAKER GTR-SLIDE WOLF SNARE SHEKERE DN BRASS+HORNS HORN HIT ZEE SNARE SHEKERE UP WII ND+REEDS BARI SAX HIT BRUSH SLAP SLAP CLAP BASS-SOUND UPRIGHT BASS SIDE STICK 1 TAMBOURINE DN BS HARMONICS SIDE STICK 2 TAMBOURINE UP FM BASS STICKS TIMBALE HI ANALOG BASS 1 STUDIO TOM TIMBALE LO ANALOG BASS 2 ROCK TOM TIMBALE RIM FRETLESS BASS 909 TOM TRIANGLE HIT MUTE BASS SYNTH DRUM VIBRASLAP SLAP BASS CYMBALS 808 CLOSED HT WHISTLE DRUM-SOUND 2001 KICK 808 OPEN HAT WOODBLOCK 808 KICK 909 CLOSED HT TUNED-PERCUS BIG BELL AMBIENT KICK 909 OPEN HAT SMALL BELL BAM KICK HOUSE CL HAT GAMELAN BELL BANG KICK PEDAL HAT MARIMBA BBM KICK PZ CL HAT MARIMBA WF BOOM KICK R&B CL HAT SOUND-EFFECT SCRATCH 1 COSMO KICK SMACK CL HAT SCRATCH 2 ELECTRO KICK SNICK CL HAT SCRATCH 3 MUFF KICK STUDIO CL HAT SCRATCH 4 PZ KICK STUDIO OPHAT1 SCRATCH 5 SNICK KICK STUDIO OPHAT2 SCRATCH 6 THUMP KICK TECHNO HAT SCRATCH LOOP TITE KICK TIGHT CL HAT WAVEFORM SAWTOOTH WILD KICK TRANCE CL HAT SQUARE WAVE WOLF KICK CR78 OPENHAT TRIANGLE WAV WOO BOX KICK COMPRESS OPHT SQR+SAW WF 808 SNARE CRASH CYMBAL SINE WAVE 808 RIMSHOT CRASH LOOP ESQ BELL WF 909 SNARE RIDE CYMBAL BELL WF BANG SNARE RIDE BELL DIGITAL WF BIG ROCK SNAR CHINA CRASH E PIANO WF -

Different Ecological Processes Determined the Alpha and Beta Components of Taxonomic, Functional, and Phylogenetic Diversity

Different ecological processes determined the alpha and beta components of taxonomic, functional, and phylogenetic diversity for plant communities in dryland regions of Northwest China Jianming Wang1, Chen Chen1, Jingwen Li1, Yiming Feng2 and Qi Lu2 1 College of Forestry, Beijing Forestry University, Beijing, China 2 Institute of Desertification Studies, Chinese Academy of Forestry, Beijing, China ABSTRACT Drylands account for more than 30% of China’s terrestrial area, while the ecological drivers of taxonomic (TD), functional (FD) and phylogenetic (PD) diversity in dryland regions have not been explored simultaneously. Therefore, we selected 36 plots of desert and 32 plots of grassland (10 Â 10 m) from a typical dryland region of northwest China. We calculated the alpha and beta components of TD, FD and PD for 68 dryland plant communities using Rao quadratic entropy index, which included 233 plant species. Redundancy analyses and variation partitioning analyses were used to explore the relative influence of environmental and spatial factors on the above three facets of diversity, at the alpha and beta scales. We found that soil, climate, topography and spatial structures (principal coordinates of neighbor matrices) were significantly correlated with TD, FD and PD at both alpha and beta scales, implying that these diversity patterns are shaped by contemporary environment and spatial processes together. However, we also found that alpha diversity was predominantly regulated by spatial structure, whereas beta diversity was largely determined by environmental variables. Among environmental factors, TD was Submitted 10 June 2018 most strongly correlated with climatic factors at the alpha scale, while 5 December 2018 Accepted with soil factors at the beta scale. -

International Journal of Research in Arts and Social Sciences Vol 1

International Journal of Research in Arts and Social Sciences Vol 1 Ethnographic Application in Igbo Communication: A Study of Selected Communities Thecla Obiora Abstract The major difference between linguistic competence and communicative competence is clearly shown in ethnography of speaking. A native speaker of a language who has communicative competence observes the social, cultural and other non-linguistic elements that govern effective communication. This principle is highly maintained in most parts of Igbo speaking areas. This research work is therefore geared towards unveiling the application of some of the cultural, social and contextual norms to some Igbo linguistic communities, with Inland West Igbo, Owere Inland East Igbo and Waawa Igbo. The researcher discovered that ethnography of communication is well observed by competent native speakers of Igbo language. This is so because sex, and age of the addresser and addressee, societal value, religious belief, etc. go a long way in determining the choice of words. The research was concluded with an emphasis that speakers of the language should adhere strictly to the ethnology of speaking so as to achieve communicative competence. This exercise would be very useful to Igbo language speakers and learners. Introduction Ethnography of communication studies language in connection with some non-linguistic factors such as the environmental factors, and socio-cultural factors. It does not study language in isolation. Ethnology of speech considers some other elements in addition to words that contribute to effective communication. In line with this, Trauth and Kerstin (2006:154) say, 2009 Page 331 International Journal of Research in Arts and Social Sciences Vol 1 This approach introduced in 1950s and early 1960s by D∙ Hymes and J∙J∙Gumperz, is concerned with the analysis of language-use in its socio cultural setting. -

IALL2017): Law, Language and Justice

Proceedings of The Fifteenth International Conference on Law and Language of the International Academy of Linguistic Law (IALL2017): Law, Language and Justice May, 16-18, 2017 Hangzhou, China and Montréal, Québec, Canada Chief Editors: Ye Ning, Joseph-G. Turi, and Cheng Le Editors: Lisa Hale, and Jin Zhang Cover Designer: Lu Xi Published by The American Scholars Press, Inc. The Proceedings of The Fifteenth International Conference on Law, Language of the International Academy of Linguistic Law (IALL2017): Law, Language, and Justice is published by the American Scholars Press, Inc., Marietta, Georgia, USA. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher. Copyright © 2017 by the American Scholars Press All rights reserved. ISBN: 978-0-9721479-7-2 Printed in the United States of America 2 Foreword In this sunny and green early summer, you, experts and delegates from different parts of the world, come together beside the Qiantang River in Hangzhou, to participate in The Fifteenth International Conference on Law and Language of the International Academy of Linguistic Law. On the occasion of the opening ceremony, it gives me such great pleasure on behalf of Zhejiang Police College, and also on my own part, to extend a warm welcome to all the distinguished experts and delegates. At the same time, thanks for giving so much trust and support to Zhejiang Police College. Currently, the law-based governance of the country is comprehensively promoted in China. As Xi Jinping, Chinese president, said, “during the entire reform process, we should attach great importance to applying the idea of rule of law and the way of rule of law to play the leading and driving role of rule of law”. -

An Atlas of Nigerian Languages

AN ATLAS OF NIGERIAN LANGUAGES 3rd. Edition Roger Blench Kay Williamson Educational Foundation 8, Guest Road, Cambridge CB1 2AL United Kingdom Voice/Answerphone 00-44-(0)1223-560687 Mobile 00-44-(0)7967-696804 E-mail [email protected] http://rogerblench.info/RBOP.htm Skype 2.0 identity: roger blench i Introduction The present electronic is a fully revised and amended edition of ‘An Index of Nigerian Languages’ by David Crozier and Roger Blench (1992), which replaced Keir Hansford, John Bendor-Samuel and Ron Stanford (1976), a pioneering attempt to synthesize what was known at the time about the languages of Nigeria and their classification. Definition of a Language The preparation of a listing of Nigerian languages inevitably begs the question of the definition of a language. The terms 'language' and 'dialect' have rather different meanings in informal speech from the more rigorous definitions that must be attempted by linguists. Dialect, in particular, is a somewhat pejorative term suggesting it is merely a local variant of a 'central' language. In linguistic terms, however, dialect is merely a regional, social or occupational variant of another speech-form. There is no presupposition about its importance or otherwise. Because of these problems, the more neutral term 'lect' is coming into increasing use to describe any type of distinctive speech-form. However, the Index inevitably must have head entries and this involves selecting some terms from the thousands of names recorded and using them to cover a particular linguistic nucleus. In general, the choice of a particular lect name as a head-entry should ideally be made solely on linguistic grounds. -

Tuning, Timbre, Spectrum, Scale William A

Tuning, Timbre, Spectrum, Scale William A. Sethares Tuning, Timbre, Spectrum, Scale Second Edition With 149 Figures William A. Sethares, Ph.D. Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering University of Wisconsin–Madison 1415 Johnson Drive Madison, WI 53706-1691 USA British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Sethares, William A., 1955– Tuning, timbre, spectrum, scale.—2nd ed. 1. Sound 2. Tuning 3. Tone color (Music) 4. Musical intervals and scales 5. Psychoacoustics 6. Music—Acoustics and physics I. Title 781.2′3 ISBN 1852337974 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Sethares, William A., 1955– Tuning, timbre, spectrum, scale / William A. Sethares. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 1-85233-797-4 (alk. paper) 1. Sound. 2. Tuning. 3. Tone color (Music) 4. Musical intervals and scales. 5. Psychoacoustics. 6. Music—Acoustics and physics. I. Title. QC225.7.S48 2004 534—dc22 2004049190 Apart from any fair dealing for the purposes of research or private study, or criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, this publication may only be reproduced, stored or transmitted, in any form or by any means, with the prior permission in writing of the publishers, or in the case of reprographic reproduction in accordance with the terms of licences issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency. Enquiries con- cerning reproduction outside those terms should be sent to the publishers. ISBN 1-85233-797-4 2nd edition Springer-Verlag London Berlin Heidelberg ISBN 3-540-76173-X 1st edition Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg New York Springer Science+Business Media springeronline.com © Springer-Verlag London Limited 2005 Printed in the United States of America First published 1999 Second edition 2005 The software disk accompanying this book and all material contained on it is supplied without any warranty of any kind. -

International Journal of Arts and Humanities (IJAH) Bahir Dar- Ethiopia Vol

IJAH 5(1), S/NO 16, JANUARY, 2016 227 International Journal of Arts and Humanities (IJAH) Bahir Dar- Ethiopia Vol. 5(1), S/No 16, January, 2016:227-235 ISSN: 2225-8590 (Print) ISSN 2227-5452 (Online) DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/ijah.v5i1.18 The Impact of the English Language on the Development of African Ethos: The Igbo Experience Akujobi, O. S. Department of English Language and Literature, Nnamdi Azikiwe University, Awka Anambra State, Nigeria E-mail: [email protected] Abstract The predominance and relegation of the English and Igbo Languages in discourse respectively have been speculated with a paucity of empirical backup. The need arises therefore for a quantitative assessment of the Impact of the English Language on the development of values (language, dressing and religion) among the Igbos. One hundred structured questionnaires were distributed, collated and analysed. The result showed that English and Igbo languages were spoken at the rate of (6%) and (76%) respectively, and that the English Language had a zero (0) impact on the mode of dressing, while its effect on religion was at the rate of only (6%) among the sampled participants. It is therefore recommended that first language (L1) be emphasized as the language of communication over second language (L2) for an overall communicative competence. Key words: English Language, African Ethos, Igbo Experience, Introduction Africa as a continent has a population of 400 million people with more than two thousand (2000) languages (Lodhi, 1993). English language for centuries has been Copyright © IAARR 2016: www.afrrevjo.net/ijah Indexed African Journals Online (AJOL) www.ajol.info IJAH 5(1), S/NO 16, JANUARY, 2016 228 viewed as a major language of communication and the official language of the African Union (AU). -

The Structure of Idioms in Ibibio

International Journal of Language and Literature December 2017, Vol. 5, No. 2, pp. 185-196 ISSN: 2334-234X (Print), 2334-2358 (Online) Copyright © The Author(s). All Rights Reserved. Published by American Research Institute for Policy Development DOI: 10.15640/ijll.v5n2a19 URL: https://doi.org/10.15640/ijll.v5n2a19 The Structure of Idioms in Ibibio Escor Efiong Udosen1, Imeobong John Offong2 & Maria-Helen Ekah3 Abstract Idioms exist in Ibibio, a Lower Cross language spoken in Nigeria. This paper attempts an investigation of the structure of this figurative language arising from the basis that they are constituents beyond the word. It relies on the Continuity Constraint framework proposed by William O‟Grady in 1998 to explain the relationship that exists among the lexical components of idioms such that they must of a necessity occur with one another to convey the meaning they do, otherwise, the meaning changes. Data were gathered from the interactions of Ibibio speakers who reside in large numbers in Calabar, Cross River State. They were extracted by the researchers‟ native speaker knowledge of the language. It is discovered that sentence idioms which are interrogatives, declaratives and imperatives occur in Ibibio. Compound idioms are also a reality in the language as well as Noun Phrase Idioms. It has also been seen that by virtue of usage, infinitive phrase and Negative constructions exist as idioms in the language. Keywords: Ibibio, Idioms, Infinitive, Phrase, Structure 1.0 Introduction Language is structured. It is a system of signs and symbols which communicate information or messages, ideas and emotions among humans. It is made up of levels which can be analysed scientifically. -

University of Cape Town

CONNECTIVES IN IGBO: A SYNTACTIC ANALYSIS OF CONNECTIVES IN THE STANDARD IGBO AND THE NSUKKA DIALECT A minor dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree of Master of Arts in Linguistics HENRIETTA CHIMTO IFYEDE (IFYHEN001) Faculty of Humanities University of Cape Town 2019 COMPULSORY DECLARATION ThisUniversity work has not been previously submittedof Cape in whole, or in part, Town for the award of any degree. It is my own work. Each significant contribution to, and quotation in, this dissertation from the work, or works, of other people has been attributed, and has been cited and referenced. Signature: Henrietta C. Ifyede Date: 25/07/2019 1 The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgement of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. Published by the University of Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. University of Cape Town Table of Contents ABSTRACT........................................................................................................................... 5 DEDICATION ..................................................................................................................................6 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ..................................................................................................................7 Chapter One ......................................................................................................................... -

Documenting the Significance of the Ibibio Traditional Marriage Gift Items: a Communicative Approach

International Journal of Language and Linguistics 2014; 2(3): 181-189 Published online April 30, 2014 (http://www.sciencepublishinggroup.com/j/ijll) doi: 10.11648/j.ijll.20140203.17 Documenting the significance of the Ibibio traditional marriage gift items: A communicative approach Bassey Andian Okon 1, Edemekong Lawson Ekpe 1, Stella Asibong Ansa 2 1Department of Linguistics and Communication Studies, University of Calabar, Calabar, Nigeria 2Department of English and Literary Studies, University of Calabar, Calabar, Nigeria Email address: [email protected] (B. A. Okon), [email protected] (E. L. Ekpe), [email protected] (S. A. Ansa) To cite this article: Bassey Andian Okon, Edemekong Lawson Ekpe, Stella Asibong Ansa. Documenting the Significance of the Ibibio Traditional Marriage Gift Items: A Communicative Approach. International Journal of Language and Linguistics. Vol. 2, No. 3, 2014, pp. 181-189. doi: 10.11648/j.ijll.20140203.17 Abstract: Marriage is one of the culture universals being that it is contracted in every society of the world, but its mode of contract varies from one society to the other. This paper unravels the significance and reasons for the traditional marriage gifts in Ibibio traditional marriage. Gifts in general, have meanings attached when given or received but most importantly, they communicate the culture of the people and other forms of emotions. Through this work, the different items given and the significance of the gifts in Ibibio traditional marriage/ culture are shown. The theoretical framework is the semiotic approach which has to do with the science of sign system or signification which is amenable to this paper. -

A Comparative Study of the Sound Systems of Ikwo Igbo and Standard Igbo Dialects Ngozi Uka Ukpai

www.idosr.org Ukpai ©IDOSR PUBLICATIONS International Digital Organization for Scientific Research ISSN: 2550-7966 IDOSR JOURNAL OF HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES 5(1): 41-57, 2020. A Comparative Study of the Sound Systems of Ikwo Igbo and Standard Igbo Dialects Ngozi Uka Ukpai Department of Languages and Linguistics Alex Ekwueme Federal University Ndufu-Alike Ebonyi State, Nigeria. Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT Development is often associated with challenges. The inability to study the numerous available dialects of Igbo language is one of the identified challenges facing the development of Igbo language particularly in the area of Igbo language teaching and learning, structural development of Igbo language, computation, and reconciliation of Igbo language with Information and Communication Technologies. Therefore, there is need to study the varying dialects of Igbo language before we can set a standard structure for the language which will facilitate a better teaching and learning of Igbo language, and harness the reconciliation of Igbo language with information and communication technologies. The present study investigated the structural differences between the sound system of Ikwo Igbo and Standard Igbo dialects. Descriptive research design was adopted for this work. However, it was largely discussed focusing on an aspect of generative phonology called feature theory. From this research, we discovered that the sound system of the two dialects are the same, except that while standard Igbo has thirty-six (36) phonemes; comprising eight (8) vowels and twenty-eight (28) consonants, the Ikwo dialect has forty-five (45) phonemes; comprising nine (9) vowels and thirty-six (36) consonants. It was observed that the sounds /s/ and /z/ cannot occur before /i/ or /ị/ in Ikwo dialect, rather /s/ and /z/ changes their forms to [ʃ] and [ʒ] respectively when the high front vowels [i] or [ɪ] is occurring after them.