Program Notes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Romantic Listening Key

Name ______________________________ Romantic Listening Key Number: 7.1 CD 5/47 pg. 297 Title: Symphonie Fantastique, 4th mvmt Composer: Berlioz Genre: Program Symphony Characteristics Texture: ____________________________________________________ Text: _______________________________________________________ Voicing/Instrumentation: orchestra What I heard: timp start, high bsn solo Number: 7.2 CD 6/11 pg 339 Title: The Moldau Composer: Smetana Genre: symphonic poem Characteristics Texture: homophonic Text: _______________________________________________________ Voicing/Instrumentation: orchestra What I heard: flute start Sections: two springs, the river, forest hunt, peasant wedding, moonlight dance of river nymphs, the river, the rapids, the river at its widest point, Vysehrad the ancient castle Name ______________________________ Number: 7.3 CD 5/51 pg 229 Title: Symphonie Fantastique, 5th mvmt (Dream of a Witch's Sabbath) Composer: Berlioz Genre: program symphony Characteristics Texture: homophonic Text: _______________________________________________________ Voicing/Instrumentation: orchestra What I heard: funeral chimes, clarinet idee fix, trills & grace notes Number: 7.4 website Title: 1812 Overture Composer: Tchaikovsky Genre: concert overture Characteristics Texture: homophonic Text: _______________________________________________________ Voicing/Instrumentation: orchestra What I heard: soft beginning, hunter motive, “Go Napoleon”, the battle Name ______________________________ Number: 7.5 website Title: The Sorcerer's Apprentice -

Celebrations Press PO BOX 584 Uwchland, PA 19480

Enjoy the magic of Walt Disney World all year long with Celebrations magazine! Receive 1 year for only $29.99* *U.S. residents only. To order outside the United States, please visit www.celebrationspress.com. Subscribe online at www.celebrationspress.com, or send a check or money order to: Celebrations Press PO BOX 584 Uwchland, PA 19480 Be sure to include your name, mailing address, and email address! If you have any questions about subscribing, you can contact us at [email protected] or visit us online! Cover Photography © Garry Rollins Issue 67 Fall 2019 Welcome to Galaxy’s Edge: 64 A Travellers Guide to Batuu Contents Disney News ............................................................................ 8 Calendar of Events ...........................................................17 The Spooky Side MOUSE VIEWS .........................................................19 74 Guide to the Magic of Walt Disney World by Tim Foster...........................................................................20 Hidden Mickeys by Steve Barrett .....................................................................24 Shutters and Lenses by Mike Billick .........................................................................26 Travel Tips Grrrr! 82 by Michael Renfrow ............................................................36 Hangin’ With the Disney Legends by Jamie Hecker ....................................................................38 Bears of Disney Disney Cuisine by Erik Johnson ....................................................................40 -

MODEST MUSSORGSKY Born March 21, 1839 in Karevo, Pskov District, Russia; Died March 28, 1881 in St

MODEST MUSSORGSKY Born March 21, 1839 in Karevo, Pskov District, Russia; died March 28, 1881 in St. Petersburg A Night on Bald Mountain (1867; arranged in 1886) Arranged by Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov (1844-1908) PREMIERE OF WORK: St. Petersburg, October 15, 1886 Russian Symphony Orchestra Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, conductor APPROXIMATE DURATION: 12 minutes INSTRUMENTATION: woodwinds in pairs plus piccolo, four horns, two trumpets, three trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion, harp and strings In the 1860s, Russian music was just beginning to find its distinctive voice. A number of composers — Balakirev, Cui, Borodin, Rimsky-Korsakov and Mussorgsky — explored native musical and folkloric sources as the basis of a national art, and became loosely confederated into a group known as “The Mighty Handful” in Russia and “The Five” in the West. Since their works took their inspiration largely from indigenous legends and folk music, Mussorgsky considered himself lucky to receive a commission in 1861 (when he was just 21) for a dramatic musical composition based on a specifically Russian subject. On January 7th, he wrote to his mentor, Balakirev, “I have received an extremely interesting commission [for music for a drama titled The Witch by his friend Baron Georgy Fyodorovitch Mengden], which I must prepare for next summer. It is this: a whole act to take place on Bald Mountain … a Witches’ Sabbath, separate episodes of sorcerers, a solemn march for all this nastiness, a finale — the glorification of the Sabbath into which is introduced the commander of the whole festival on the Bald Mountain. The libretto is very good. I already have some material for it; it may turn out to be a very good thing.” The mountain to which Mussorgsky referred, well known in Russian legend, is Mount Triglav, near Kiev, reputed to be the site of the annual witches’ sabbath that occurs on St. -

Boatman's Quarterly Review

boatman’s quarterly review the journal of the Grand Canyon River Guide’s, Inc. • voulme 32 number 4 winter 2019 – 2020 the journal of Grand Canyon River Guide’s, Changing of the Guard • Prez Blurb • GCRRA • Farewells • Bug Flows Meaning of Wilderness • BQR Digital Trip • Old Guide New Tricks • Tuweep Science and Dam Ops • Dammed • GC Protection Act • Back of the Boat • Contributors boatman’s quarterly review Changing of the Guard …is published more or less quarterly by and for GRAND CANYON RIVER GUIDES. NOTHER JOURNEY AROUND THE SUN—where does GRAND CANYON RIVER GUIDES the time go? It’s time to say goodbye and is a nonprofit organization dedicated to Aextend our heartfelt thanks to our outgoing president, Doc Nicholson, and the wonderful Protecting Grand Canyon GCRG board members who finished their terms on Setting the highest standards for the river profession September 1ST—Mara Drazina, Derik Spice, and Celebrating the unique spirit of the river community Thea Sherman. Doc served on the GCRG board back Providing the best possible river experience in 2008, and then volunteered again to run as VP in 2017, segueing to president in 2018, a decade after he General Meetings are held each Spring and Fall. Our first got involved with GCRG. With more than forty Board of Directors Meetings are generally held the first seasons of river running under his belt, Doc had seen Wednesday of each month. All innocent bystanders are lots changes—along the river, in our guide culture, urged to attend. Call for details. in park policies. His depth of experience was a great GCRG STAFF boon to as we navigated issues large and small. -

Boxoffice Barometer (March 6, 1961)

MARCH 6, 1961 IN TWO SECTIONS SECTION TWO Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer presents William Wyler’s production of “BEN-HUR” starring CHARLTON HESTON • JACK HAWKINS • Haya Harareet • Stephen Boyd • Hugh Griffith • Martha Scott • with Cathy O’Donnell • Sam Jaffe • Screen Play by Karl Tunberg • Music by Miklos Rozsa • Produced by Sam Zimbalist. M-G-M . EVEN GREATER IN Continuing its success story with current and coming attractions like these! ...and this is only the beginning! "GO NAKED IN THE WORLD” c ( 'KSX'i "THE Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer presents GINA LOLLOBRIGIDA • ANTHONY FRANCIOSA • ERNEST BORGNINE in An Areola Production “GO SPINSTER” • • — Metrocolor) NAKED IN THE WORLD” with Luana Patten Will Kuluva Philip Ober ( CinemaScope John Kellogg • Nancy R. Pollock • Tracey Roberts • Screen Play by Ranald Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer pre- MacDougall • Based on the Book by Tom T. Chamales • Directed by sents SHIRLEY MacLAINE Ranald MacDougall • Produced by Aaron Rosenberg. LAURENCE HARVEY JACK HAWKINS in A Julian Blaustein Production “SPINSTER" with Nobu McCarthy • Screen Play by Ben Maddow • Based on the Novel by Sylvia Ashton- Warner • Directed by Charles Walters. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer presents David O. Selznick's Production of Margaret Mitchell’s Story of the Old South "GONE WITH THE WIND” starring CLARK GABLE • VIVIEN LEIGH • LESLIE HOWARD • OLIVIA deHAVILLAND • A Selznick International Picture • Screen Play by Sidney Howard • Music by Max Steiner Directed by Victor Fleming Technicolor ’) "GORGO ( Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer presents “GORGO” star- ring Bill Travers • William Sylvester • Vincent "THE SECRET PARTNER” Winter • Bruce Seton • Joseph O'Conor • Martin Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer presents STEWART GRANGER Benson • Barry Keegan • Dervis Ward • Christopher HAYA HARAREET in “THE SECRET PARTNER” with Rhodes • Screen Play by John Loring and Daniel Bernard Lee • Screen Play by David Pursall and Jack Seddon Hyatt • Directed by Eugene Lourie • Executive Directed by Basil Dearden • Produced by Michael Relph. -

Ferde Grofé (1892-1972)

Composer Fact Sheets Ferde Grofé (1892-1972) FAST FACTS • Born into four generations of musicians • Studied piano, viola & composition in Germany • Arranged jazz and popular compositions for dance and jazz big bands • Inspired to write Grand Canyon Suite after watching the sunrise over the Grand Canyon Born: 1892 (New York City, NY) Died: 1972 (Santa Monica, CA) Ferdinand Rudolph von Grofé, or just “Ferde”, was born into four generations of talented musicians. He was born in New York, but his mother later took him to Germany to study piano, viola, and composition. In addition to these, he mastered other string and brass instruments and actually played viola in the Los Angeles Philharmonic. Ferde’s talent on many different instruments led him to try to arrange famous works for the jazz and dance bands he performed with. His successful arrangement of Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue caused him to be noticed by Paul Whiteman, a popular jazz bandleader in the 1920s. In addition to the pieces he arranged, Ferde wrote some of his own. Mississippi: A Journey in Tones , Metropolis: A Fantasie in Blue , and the Grand Canyon Suite paint portraits of the American landscape, much like what Aaron Copland sought to do. Grand Canyon Suite is Ferde’s best-known work. He shared many years after it was written that it was inspired by a road trip he and his friends took from California to Arizona to watch the sun rise over the Grand Canyon. At first, he described, the scenery was very calm and quiet. As the sun began to come up, however, he began to hear all of the noises of nature around him. -

Fantasias Music History Through Animation Background

Disney’s Two Fantasias Music History Through Animation Background “The beauty and inspiration of music must not be restricted to a privileged few, but must be made available to every man, woman and child.” - Leopold Stokowski, 1940 “Fantasia is.. the beginning of a new technique for the screen.. and a greater development of sound recording and reproduction.” - Walt Disney, 1940 - Disney’s idea of marrying animation and music had begun in 1929 with the Silly Symphonies series (The Skeleton Dance, 1929, Flowers and Trees, 1932, first Technicolor release, The Old Mill, 1937, first multi-plane animation). Mickey was purposely left out. - by late-1930’s, Mickey’s popularity was failing, so Disney conceived the idea of starring Mickey in a Silly Symphony based on Paul Dukas’ The Sorcerer’s Apprentice - Disney ran into Stokowski in a Beverly Hills restaurant and discussed the idea with him. They soon elaborated it into a feature length film consisting of several contrasting musical works. Disney at first called it The Concert Feature. - Stokowski suggested Fantasia, a musical term meaning “a composition unrestricted by formal design, free reign for fantasy and imagination” - originally conceived as a continually changing concert program, with new pieces added and old ones withdrawn on a continuing basis. Leopold Stokowski • born in London, 1882 emigrated to New York in 1905 • 1912 conductor of Philadelphia Orchestra • an early champion of recorded orchestra music - • “The recording process will one day reproduce music better than heard in the concert hall” • experiments with 3-channel stereo sound at Bell Labs • Philadelphia Orchestra transmitted over three phone lines to Washington, DC • unconventional positioning of instruments in order to produce a better recording • conducted without a baton (hands only), as shown in Fantasia and parodied in Long Haired Hare • by 1937 was well known to American audiences through film & radio appearances • had developed a 9 microphone recording system (mixed to mono) for earlier film recording. -

TCNJ Orchestra Repertoire • Bach

TCNJ Orchestra Repertoire • Bach - Brandenburg No. 1 • Bach - Brandenburg No. 3 for Strings • Bach: Brandenburg Concerto No.5 • Barber: 1st Essay for Orchestra • Bartók - Magyar Képek (Hungarian Pictures) • Bartók - Roumanian Dances • Beethoven: Symphony No. 5 • Beethoven: Symphony No.6 (Pastorale) • Beethoven - Coriolanus • Beethoven - Egmont • Beethoven - Fidelio • Beethoven - Piano Concerto No. 3 in C Minor • Beethoven - The Ruins of Athens • Beethoven: Choral Fantasie • Beethoven: Leonora No.3 • Beethoven: Violin Concerto in D • Bernstein - Candide • Bernstein - Symphonic Dances from West Side Story • Bizet - Carmen Suites 1 & 2 • Bizet - Jeux d'Enfants • Britten - Soirées Musicales Op. 9 • Bruch Violin Concerto No.1 in E minor Op.26 • Castelnuovo Tedesco - Concerto in D (Guitar) • Chabrier - Espana • Chabrier: Habanera • Chaminade - Concertino for Flute and Orchestra • Copland - Billy the Kid • Copland - Rodeo • Creston - Accordion Concerto • De Falla - Scenes and Dances from the "Three Cornered Hat" • Debussy - Petite Suite • Debussy - Prélude á l'après midi d'un Faune • Delius - The Walk to the Paradise Garden • Dvořák - Symphony No. 8 in G • Dvořák – Piano Quintet, Op. 81 • Dvořák: Symphony No.9 (From the New World) • Elgar: Cello Concerto in E minor • Elgar-Nimrod from 'The Enigma Variations' • Fauré - Bergamaster Suite • Fauré - Prelude from Pelleas and Melisande • Gershwin - Rhapsody in Blue • Gershwin: Cuban Overture • Ginestera - Danza del Trigo from "Estancia" • Glazunov-Violin Concerto in A Minor • Glinka - Russlan and Ludmilla • Gounod - Faust - Ballet Music • Grieg - Notturno from 'Lyric Suite' Op. 54 No. 3 • Grieg - Piano Concerto in A Minor Op 6 • Grieg - Triumphal March from "Sigurd Jorsalfar" • Haas- Sieben Klangräume • Haydn - Symphony No. 49 in F minor • Humperdink-Hansel and Gretel (Prelude) • Ives - The Unanswered question • Ives: Central Park in the Dark • Khachaturian: "Masquerade" Suite • Kodaly: Hary Janos • Lalo - Scherzo in D minor • Lalo: Le Roi d'Ys • Lecuona - Spanish Dances • Leighton – Festive • Mahler – Symphony No. -

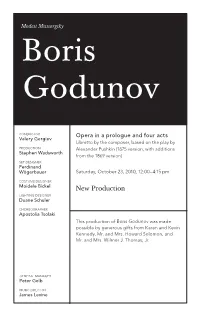

Boris Godunov

Modest Mussorgsky Boris Godunov CONDUCTOR Opera in a prologue and four acts Valery Gergiev Libretto by the composer, based on the play by PRODUCTION Alexander Pushkin (1875 version, with additions Stephen Wadsworth from the 1869 version) SET DESIGNER Ferdinand Wögerbauer Saturday, October 23, 2010, 12:00–4:15 pm COSTUME DESIGNER Moidele Bickel New Production LIGHTING DESIGNER Duane Schuler CHOREOGRAPHER Apostolia Tsolaki This production of Boris Godunov was made possible by generous gifts from Karen and Kevin Kennedy, Mr. and Mrs. Howard Solomon, and Mr. and Mrs. Wilmer J. Thomas, Jr. GENERAL MANAGER Peter Gelb MUSIC DIRECTOR James Levine 2010–11 Season The 268th Metropolitan Opera performance of Modest Mussorgsky’s Boris Godunov Conductor Valery Gergiev in o r d e r o f v o c a l a p p e a r a n c e Nikitich, a police officer Xenia, daughter of Boris Valerian Ruminski Jennifer Zetlan Mitiukha, a peasant Feodor, son of Boris Mikhail Svetlov Jonathan A. Makepeace Shchelkalov, a boyar Nurse, nanny to Boris’s Alexey Markov children Larisa Shevchenko Prince Shuisky, a boyar Oleg Balashov Boyar in Attendance Brian Frutiger Boris Godunov René Pape Marina Ekaterina Semenchuk Pimen, a monk Mikhail Petrenko Rangoni, a Jesuit priest Evgeny Nikitin Grigory, a monk, later pretender to the Russian throne Holy Fool Aleksandrs Antonenko Andrey Popov Hostess of the Inn Chernikovsky, a Jesuit Olga Savova Mark Schowalter Missail Lavitsky, a Jesuit Nikolai Gassiev Andrew Oakden Varlaam Khrushchov, a boyar Vladimir Ognovenko Dennis Petersen Police Officer Gennady Bezzubenkov Saturday, October 23, 2010, 12:00–4:15 pm This afternoon’s performance is being transmitted live in high definition to movie theaters worldwide. -

The Signal, Vol. 73, No. 14 (April 30, 1959)

"The D esk Set" Awaits Weekend Opening Featuring Simulated Electronic Computor tate ignal VOL. LXXIII, No. 14 TRENTON STATE COLLEGE THURSDAY, APRIL 30, 1959 Ashenfelter Elected Initial Arts Festival Commences ToBoardPresidency yarieci Renowned Exhibits The officers for the 1959-1960 Exec utive Board were elected at a meeting held on Monday night. Jack Ashen Weeklong Program Opens Monday felter will serve as President. He is a sophomore, science major who Monday the first annual Spring Festival of Arts will begin on served as a Board Vice-President dur Joyce Coleman shows some of the Emmarac Electronic Brain to several of the girls the Trenton State College campus. Designed to aid the cultural who ar e starring in "The Desk Set" Friday and Saturday night. Looking on are Gloria ing the past year. development of students and Alumni, the weeklong Festival will Weinstein, Nancy Cartwright, Linda Lawson, and Babs Gibson. —Photo by Lipsen Elected as first Vice-President was feature prominent artists and works from various fields. Dave Knauth, junior, elementary. Throughout the week, there will be exhibits in painting, crafts, Trenton State Thespians will again Jim Sherry. Members of the crew Second Vice-President is Van Titus, and photography. Painting exhibitions will be seen in Phelps Hall, show the ir talents as the curtain rises are Joe Papparone, Nancy Cartwright, junior, phys. ed. and Centennial Lounge. Photography on "The Desk Set" this Friday and Bill Cullen, Cora Jackette, Judy Gal- The four secretaries for the new and tape recordings will be seen in Saturday night in Kendall Hall. A lina, Linda Lawson, and Joan Pointon. -

From Grand Canyon Suite by Ferdinand Grofé Page 14

American Odyssey STUDENT JOURNAL THIS BELONGS TO: _________________________ CLASS: __________________________________ 1 WHO IS TAKING YOU ON AN ODYSSEY? 2 There are many ways that a conductor can arrange the seating of the musicians for a particular work or concert. The above is an example of one of the common ways that the conductor places the instruments. When you go to the concert, see if the instruments are arranged like this picture. If they are not the same as this picture, which instruments are in different places? __________________________________________________________________________________ What instruments sometimes play with the orchestra and are not in this picture? __________________________________________________________________________________ What instruments usually are not included in an orchestra? __________________________________________________________________________________ Find TheYoung Person’s Guide to the Symphony at www.jwjonline.net, which gives more information on the instruments. Go to www.DSOKids.com to listen to each instruments (go to Listen, then By Instrument). 3 MEET THE CONDUCTORS! Philip Mann, Music Director and Conductor of the Arkansas Symphony Orchestra grew up in Durango, Colorado. He attended school on an Indian reservation and lived on a ranch with horses and dogs in the mountains. He started playing the violin at age 5 and the bassoon at age 12 and loved music as a child, but didn’t always like to practice (now he is glad he did). Mr. Mann studied engineering, political science and physics in college, but then decided to make music his life. Mr. Mann chose to learn how to conduct because his step-father was a conductor and teacher. He participated in the Hot Springs Music Festival in 2006 and loves Hot Springs and Little Rock! He enjoys fly-fishing, hiking, reading and playing and watching sports. -

1. 101 Strings: Panoramic Majesty of Ferde Grofe's Grand

1. 101 Strings: Panoramic Majesty Of Ferde Grofe’s Grand Canyon Suite 2. 60 Years of “Music America Loves Best” (2) 3. Aaron Rosand, Rolf Reinhardt; Southwest German Radio Orchestra: Berlioz/Chausson/Ravel/Saint-Saens 4. ABC: How To Be A Zillionaire! 5. ABC Classics: The First Release Seon Series 6. Ahmad Jamal: One 7. Alban Berg Quartett: Berg String Quartets/Lyric Suite 8. Albert Schweitzer: Mendelssohn Organ Sonata No. 4 In B-Flat Major/Widor Organ Symphony No. 6 In G Minor 9. Alexander Schneider: Brahms Piano Quartets Complete (2) 10. Alexandre Lagoya & Claude Bolling: Concerto For Classic Guitar & Jazz Piano 11. Alexis Weissenberg, Georges Pretre; Chicago Symphony Orchestra: Rachmaninoff Concerto No. 3 12. Alexis Weissenberg, Herbert Von Karajan; Orchestre De Paris: Tchaikovsky Concerto #2 13. Alfred Deller; Deller Consort: Gregorian Chant-Easter Processions 14. Alfred Deller; Deller Consort: Music At Notre Dame 1200-1375 Guillaume De Machaut 15. Alfred Deller; Deller Consort: Songs From Taverns & Chapels 16. Alfred Deller; Deller Consort: Te Deum/Jubilate Deo 17. Alfred Newman; Brass Of The Hollywood Bowl Symphony Orchestra: Hallelujah! 18. Alicia De Larrocha: Grieg/Mendelssohn 19. Andre Cluytens; Paris Conservatoire Orchestra: Bizet 20. Andre Kostelanetz & His Orchestra: Columbia Album Of Richard Rodgers (2) 21. Andre Kostelanetz & His Orchestra: Verdi-La Traviata 22. Andre Previn; London Symphony Orchestra: Rachmaninov/Shostakovich 23. Andres Segovia: Plays J.S. Bach//Edith Weiss-Mann Harpsichord Bach 24. Andy Williams: Academy Award Winning Call Me Irresponsible 25. Andy Williams: Columbia Records Catalog, Vol. 1 26. Andy Williams: The Shadow Of Your Smile 27. Angel Romero, Andre Previn: London Sympony Orchestra: Rodrigo-Concierto De Aranjuez 28.