About the Exhibition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Islamic Geometric Patterns Jay Bonner

Islamic Geometric Patterns Jay Bonner Islamic Geometric Patterns Their Historical Development and Traditional Methods of Construction with a chapter on the use of computer algorithms to generate Islamic geometric patterns by Craig Kaplan Jay Bonner Bonner Design Consultancy Santa Fe, New Mexico, USA With contributions by Craig Kaplan University of Waterloo Waterloo, Ontario, Canada ISBN 978-1-4419-0216-0 ISBN 978-1-4419-0217-7 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-1-4419-0217-7 Library of Congress Control Number: 2017936979 # Jay Bonner 2017 Chapter 4 is published with kind permission of # Craig Kaplan 2017. All Rights Reserved. This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the publisher nor the authors or the editors give a warranty, express or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made. -

Textile Society of America Newsletter 29:2 — Fall 2017 Textile Society of America

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Textile Society of America Newsletters Textile Society of America Fall 2017 Textile Society of America Newsletter 29:2 — Fall 2017 Textile Society of America Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsanews Part of the Art and Materials Conservation Commons, Fashion Design Commons, Fiber, Textile, and Weaving Arts Commons, Industrial and Product Design Commons, Interdisciplinary Arts and Media Commons, and the Metal and Jewelry Arts Commons Textile Society of America, "Textile Society of America Newsletter 29:2 — Fall 2017" (2017). Textile Society of America Newsletters. 80. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsanews/80 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Textile Society of America at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Textile Society of America Newsletters by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. VOLUME 29. NUMBER 2. FALL 2017 Photo Credit: Tourism Vancouver See story on page 6 Newsletter Team BOARD OF DIRECTORS Editor-in-Chief: Wendy Weiss (TSA Board Member/Director of Communications) Designer: Meredith Affleck Vita Plume Member News Editor: Caroline Charuk (TSA General Manager) President [email protected] Editorial Assistance: Natasha Thoreson and Sarah Molina Lisa Kriner Vice President/President Elect Our Mission [email protected] Roxane Shaughnessy The Textile Society of America is a 501(c)3 nonprofit that provides an international forum for Past President the exchange and dissemination of textile knowledge from artistic, cultural, economic, historic, [email protected] political, social, and technical perspectives. Established in 1987, TSA is governed by a Board of Directors from museums and universities in North America. -

Learning at the Aga Khan Museum: a Curriculum Resource Guide for Teachers, Grades One to Eight

Learning at the Aga Khan Museum A Curriculum Resource Guide for Teachers Grades One to Eight INTRODUCTION TO THE AGA KHAN MUSEUM The Aga Khan Museum in Toronto, Canada is North America’s first museum dedicated to the arts of Muslim civilizations. The Museum aims to connect cultures through art, fostering a greater understanding of how Muslim civilizations have contributed to world heritage. Opened in September 2014, the Aga Khan Museum was established and developed by the Aga Khan Trust for Culture (AKTC), an agency of the Aga Khan Development Network (AKDN). Its state-of-the-art building, designed by Japanese architect Fumihiko Maki, includes two floors of exhibition space, a 340-seat auditorium, classrooms, and public areas that accommodate programming for all ages and interests. The Aga Khan Museum’s Permanent Collection spans the 8th century to the present day and features rare manuscript paintings, individual folios of calligraphy, metalwork, scientific and musical instruments, luxury objects, and architectural pieces. The Museum also publishes a wide range of scholarly and educational resources; hosts lectures, symposia, and conferences; and showcases a rich program of performing arts. Learning at the Aga Khan Museum A Curriculum Resource Guide for Teachers Grades One to Eight Patricia Bentley and Ruba Kana’an Written by Patricia Bentley, Education Manager, Aga Khan All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be Museum, and Ruba Kana’an, Head of Education and Scholarly reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any Programs, Aga Khan Museum, with contributions by: form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, or otherwise, without prior consent of the publishers. -

Signifying Notiiing That Which Is Not There

liUlillIMI.IIJ thresholds 19 Signifying Notiiing This article seeks to ground itself In two literal understandings of the invisible, that is, as something, which is simply not there, or as some- thing which has been hidden. It works out from the intuitive response to the human body as a commonplace object with which we are all inti- mately familiar, and of which we commonly expected a state of com- plete presence to be normal. The body is of course also an object to which strategies of covering and exposure are applied, in a highly differ- entiated set of systems across times and cultures. That Which Is Not There A discomforting thought. I had sufficient elbow room to begin writing this on a Greyhound bus only because the young woman seated next to me had no arm from above the elbow, or at least, from above where her elbow should have been. That which is not there grasps, uninvited, our attention. j^ ^^^ ^^^^ ^^^ ^^^ ^^ ^^^ other. Another story about a chair and a missing arm. There is a chair, designed by Lutyens that has but one arm. One cannot sit in this chair without assuming a certain pose, legs crossed, left hand resting, fingers curled, on one's right thigh, right hand, raised to the chin, perhaps fram- ing one's mouth, holding the others' attention to one's face, one's con- versation. It is difficult for anyone at all comfortable within his or her own skin not to assume that pose, or the demeanor which that pose accompanies. If one is not comfortable, the only choice is to sit bolt "We deliberately left out one arm- upright, hands together on one's lap, perhaps fidgeting the one with the rest to give more ease to the body. -

De Divino Errore ‘De Divina Proportione’ Was Written by Luca Pacioli and Illustrated by Leonardo Da Vinci

De Divino Errore ‘De Divina Proportione’ was written by Luca Pacioli and illustrated by Leonardo da Vinci. It was one of the most widely read mathematical books. Unfortunately, a strongly emphasized statement in the book claims six summits of pyramids of the stellated icosidodecahedron lay in one plane. This is not so, and yet even extensively annotated editions of this book never noticed this error. Dutchmen Jos Janssens and Rinus Roelofs did so, 500 years later. Fig. 1: About this illustration of Leonardo da Vinci for the Milanese version of the ‘De Divina Proportione’, Pacioli erroneously wrote that the red and green dots lay in a plane. The book ‘De Divina Proportione’, or ‘On the Divine Ratio’, was written by the Franciscan Fra Luca Bartolomeo de Pacioli (1445-1517). His name is sometimes written Paciolo or Paccioli because Italian was not a uniform language in his days, when, moreover, Italy was not a country yet. Labeling Pacioli as a Tuscan, because of his birthplace of Borgo San Sepolcro, may be more correct, but he also studied in Venice and Rome, and spent much of his life in Perugia and Milan. In service of Duke and patron Ludovico Sforza, he would write his masterpiece, in 1497 (although it is more correct to say the work was written between 1496 and 1498, because it contains several parts). It was not his first opus, because in 1494 his ‘Summa de arithmetic, geometrica, proportioni et proportionalita’ had appeared; the ‘Summa’ and ‘Divina’ were not his only books, but surely the most famous ones. For hundreds of years the books were among the most widely read mathematical bestsellers, their fame being only surpassed by the ‘Elements’ of Euclid. -

Downloaded from Brill.Com09/27/2021 10:32:48PM Via Free Access 266 Index

Index ʿAbd al-Nāṣir, Jamāl (Nasser) 233, 234 Almássy, László 233 ʿAbd al-Raḥmān 143, 144, 151, 152, 154 Americas 171 Abd-el-Wahad (Moroccan resident in Mecca) American Oil Company 230 128 Arab Abdülhamid ii (Sultan-Caliph and Khādim Bureau/Bureaux arabes (military system of al-Ḥaramayn) 71, 115 administration) 96, 121 ʿAbdullāh Saʿīd al-Damlūjī 196 hygiene 194 Abdur Rahman 95, 96 migrants in Poland 156 Ablonczy, Balázs 227 Revolt 96, 97 Abraham 137, 166 Arabia (see Saudi Arabia) Abul Fazl 23 Arabian Abu-Qubays (mount) 128 Peninsula 5, 119, 143 Aceh 28, 93 horse, walking on pilgrims 166 Aden 11, 25, 90, 96, 99, 101, 145, 154 architecture 166 Afghanistan 95, 103, 115, 207 music and dancing girls 165, 167 Africa 34, 41, 81, 95, 99, 113, 121, 143, 144, 148, sea 21 150, 171, 192, 198, 240 ʿArafāt África ( journal) 261 the Day of 209, 210, 211 Africanism 241 the Mountain of 90, 151, 185, 200, 201, 204, Akbar Nama 23 207, 209, 210, 223 Akbar (Emperor) 23, 30, 37 the Plain of 97, 212 ʿAlawī, Aḥmad b. Muṣṭafā al- 251 Arenberg (d’), Auguste 130 ʿAlawiyya (Sufi order) 251 Armenian 4, 148 Al-Azhar x, 221, 222, 223, 232, 233, 234, 259 Attas, Said Hossein al- 201 Album with photographs of Polish mosques Asad, Muḥammad (Weiss, Leopold) 174, 195 177 Asia 10, 16, 17, 20, 21, 24, 30, 34, 38, 43, 47, 52, Albuquerque, Alfonso de 19 59, 81, 95, 107 Alcohol 150, 230 Assimilationist 212 Alexandria 143, 144, 154, 222, 227, 229, 240, Asssemblé Nationale (French Parliament) 249, 258 121 Alexandria Aurangzeb 31 Fuad i Airport in 257 Australia 171 Spanish consul -

Simple Rules for Incorporating Design Art Into Penrose and Fractal Tiles

Bridges 2012: Mathematics, Music, Art, Architecture, Culture Simple Rules for Incorporating Design Art into Penrose and Fractal Tiles San Le SLFFEA.com [email protected] Abstract Incorporating designs into the tiles that form tessellations presents an interesting challenge for artists. Creating a viable M.C. Escher-like image that works esthetically as well as functionally requires resolving incongruencies at a tile’s edge while constrained by its shape. Escher was the most well known practitioner in this style of mathematical visualization, but there are significant mathematical objects to which he never applied his artistry including Penrose Tilings and fractals. In this paper, we show that the rules of creating a traditional tile extend to these objects as well. To illustrate the versatility of tiling art, images were created with multiple figures and negative space leading to patterns distinct from the work of others. 1 1 Introduction M.C. Escher was the most prominent artist working with tessellations and space filling. Forty years after his death, his creations are still foremost in people’s minds in the field of tiling art. One of the reasons Escher continues to hold such a monopoly in this specialty are the unique challenges that come with creating Escher type designs inside a tessellation[15]. When an image is drawn into a tile and extends to the tile’s edge, it introduces incongruencies which are resolved by continuously aligning and refining the image. This is particularly true when the image consists of the lizards, fish, angels, etc. which populated Escher’s tilings because they do not have the 4-fold rotational symmetry that would make it possible to arbitrarily rotate the image ± 90, 180 degrees and have all the pieces fit[9]. -

The Arab and Arab Islamic and Muslim Architecture

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. THE ARAB AND ARAB ISLAMIC AND MUSLIM ARCHITECTURE OF THE OLD HOLY MASJID AND AL-KA'ABAH A Monadic Interpretation of the Two Holy Buildings by Eduard Franciscus Schwarz A Thesis Submitted to Massey University Wellington Campus, New Zealand in Part Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Philosophy Massey University of Wellington 2005 The Holy Complex in Makkah al-Mukarramah in Saudi Arabia Acknowledgments Although I belong to those who were indirectly indoctrinated by the Bauhaus, Architecture has moved well away from the Bauhaus architecture and Bauhaus philosophy into that can be referred to as labyrinth architecture with a poetic base. However, the tendency to perceive architecture as a body poetic needs to be queried. That architecture had moved away from the architecture advocated by the Bauhaus was particularly realized during my study at Massey University, Wellington Campus, during 2004. Contact with art students and staff, trained in art and fashion were very useful. Without the help of others, the writing of the thesis would have been more difficult. My thanks go to Professor Duncan Joiner, who was my supervisor. I am also thankful to the Massey University Library, Wellington Campus that carried out a literature search in support of this work. Massey University also provided me with computers for the writing of the work, Brian Halliday, now retired, needs mentioning here, so does Ken Elliot for the constant help he gave computer-wise. -

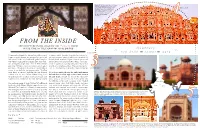

FROM the INSIDE ARCHITECTURE in RELATION to the F E M a L E FORM in the TIME of the INDIAN MUGHAL EMPIRE Itinerary

Days 5-8 - Exploration of the city of Jaipur with focus on Moghul architecture, such as the HAWA MAHAL located within days in Jaipur the Royal Palace. The original intent of the lattice design was to allow royal ladies to observe everyday life and festivals celebrated in the street below without being seen. 4 FROM THE INSIDE ARCHITECTURE IN RELATION TO THE F e m a l e FORM IN THE TIME OF THE INDIAN MUGHAL EMPIRE itinerary b e g i n* new delhi jaipur agra If you wander through the hot and crowded streets of windows, called jharokas, that acted as screens be- Jaipur, meander through the grand palace gates, and tween these private quarters and the exterior world. On days in New Delhi find yourself in the very back of the palace complex, the other hand, women held power in these spaces, and you will be confronted by a unique, five story struc- molded these environments to their wills. Their quar- ture of magnificent splendor. It is the Hawa Mahal, ters were organized according to the power they welded and it has 953 lattice covered windows carved out of over the men who housed them. Thus, architecture be- *first and last days are pink stone. Designed in the shape of Lord Krishna’s came the threshold that framed these women’s worlds. reserved3 for travel crown, it was built for one purpose only. To allow royal ladies to observe everyday life and festivals We seek to explore the way the built environment celebrated in the street below without being seen. -

Leonardo Universal

Leonardo Universal DE DIVINA PROPORTIONE Pacioli, legendary mathematician, introduced the linear perspective and the mixture of colors, representing the human body and its proportions and extrapolating this knowledge to architecture. Luca Pacioli demonstrating one of Euclid’s theorems (Jacobo de’Barbari, 1495) D e Divina Proportione is a holy expression commonly outstanding work and icon of the Italian Renaissance. used in the past to refer to what we nowadays call Leonardo, who was deeply interested in nature and art the golden section, which is the mathematic module mathematics, worked with Pacioli, the author of the through which any amount can be divided in two text, and was a determined spreader of perspectives uneven parts, so that the ratio between the smallest and proportions, including Phi in many of his works, part and the largest one is the same as that between such as The Last Supper, created at the same time as the largest and the full amount. It is divine for its the illustrations of the present manuscript, the Mona being unique, and triune, as it links three elements. Lisa, whose face hides a perfect golden rectangle and The fusion of art and science, and the completion of the Uomo Vitruviano, a deep study on the human 60 full-page illustrations by the preeminent genius figure where da Vinci proves that all the main body of the time, Leonardo da Vinci, make it the most parts were related to the golden ratio. Luca Pacioli credits that Leonardo da Vinci made the illustrations of the geometric bodies with quill, ink and watercolor. -

The Amalgamation of Indo-Islamic Architecture of the Deccan

Islamic Heritage Architecture and Art II 255 THE AMALGAMATION OF INDO-ISLAMIC ARCHITECTURE OF THE DECCAN SHARMILA DURAI Department of Architecture, School of Planning & Architecture, Jawaharlal Nehru Architecture & Fine Arts University, India ABSTRACT A fundamental proportion of this work is to introduce the Islamic Civilization, which was dominant from the seventh century in its influence over political, social, economic and cultural traits in the Indian subcontinent. This paper presents a discussion on the Sultanate period, the Monarchs and Mughal emperors who patronized many arts and skills such as textiles, carpet weaving, tent covering, regal costume design, metallic and decorative work, jewellery, ornamentation, painting, calligraphy, illustrated manuscripts and architecture with their excellence. It lays emphasis on the spread of Islamic Architecture across India, embracing an ever-increasing variety of climates for the better flow of air which is essential for comfort in the various climatic zones. The Indian subcontinent has produced some of the finest expressions of Islamic Art known to the intellectual and artistic vigour. The aim here lies in evaluating the numerous subtleties of forms, spaces, massing and architectural character which were developed during Muslim Civilization (with special reference to Hyderabad). Keywords: climatic zones, architectural character, forms and spaces, cultural traits, calligraphic designs. 1 INTRODUCTION India, a land enriched with its unique cultural traits, traditional values, religious beliefs and heritage has always surprised historians with an amalgamation of varying influences of new civilizations that have adapted foreign cultures. The advent of Islam in India was at the beginning of 11th century [1]. Islam, the third great monotheistic religion, sprung from the Semitic people and flourished in most parts of the world. -

06 CAPITOLO.Pdf

POLITECNICO DI TORINO Repository ISTITUZIONALE Un modo della visione tra passato e futuro: Rilievo, conoscenza e rappresentazione dell’ornatus in architettura Original Un modo della visione tra passato e futuro: Rilievo, conoscenza e rappresentazione dell’ornatus in architettura / Tizzano, Antonella. - (2012). Availability: This version is available at: 11583/2497377 since: Publisher: Politecnico di Torino Published DOI:10.6092/polito/porto/2497377 Terms of use: Altro tipo di accesso This article is made available under terms and conditions as specified in the corresponding bibliographic description in the repository Publisher copyright (Article begins on next page) 05 October 2021 Motivi ornamentali 995 6 Motivi ornamentali 996 Motivi ornamentali Motivi ornamentali 997 6.1 Icone e figure Nel corso della sua storia, l'Islam ha spesso manifestato, per voce dei suoi giuristi, una certa diffidenza nei confronti delle figure. Basandosi sull'interpretazione di alcuni passi del Corano e facendo riferimento agli hadith, i discorsi del Profeta, alcuni dottori della legge hanno sviluppato un'argomentazione secondo la quale la raffigurazione di esseri viventi, essendo contraria alla volontà divina, fosse da condannare. Questo atteggiamento dipende dall'opinione dei giuristi, secondo i quali, riprodurre un'immagine di un essere vivente dotato del soffio vitale, significherebbe contraffare l'opera divina della creazione1. E' probabile che un tale atteggiamento dogmatico abbia distolto gli artisti dalle arti figurative anche se non risulta che questa legge sia mai stata formulata, né che sia stata rispettata con lo stesso rigore in ogni epoca e in ogni luogo. I resti archeologici omayyadi conservano molte tracce di una decorazione architettonica di natura figurativa2 ed esistono testimonianze appartenenti alle epoche abbaside e ghaznavide ma sono tutte collocate in residenze reali, cioè in edifici che diversamente dai luoghi di culto, sfuggono ad implicazioni di tipo religioso3.