University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation Formatting

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PA 4-H Horse Cloverbud Activity Book B

PA 4-H Horse Cloverbud Activity Book B Name: Club Name: County: Thank you for helping with the PA 4-H Horse Cloverbud Program! Here are some notes to help you lead this project: The PA 4-H Horse Cloverbud Policy & Safety Guidelines must be followed at all times when using this activity book. Please see your Extension Office or http://extension.psu.edu/4-h/projects/ horses/cloverbud-program/cloverbud-policy-and-guidelines for a copy of the policy and guidelines. Many sections include a variety of activities. At least one activity per section must be completed. There will be three PA 4-H Horse Cloverbud Activity Books. All Cloverbud members in one club or group should complete the same book in the course of one year, regardless of their ages or the length of time they have been members. Ex: This year, all Cloverbud Horse Club members complete Book B. Next year, all members will complete Book C, etc. Currently, this curriculum is available as an electronic publication. Please contact your local Extension Office for printed copies. For additional Cloverbud activities, please refer to our Leader & Educator Resource page located at http://extension.psu.edu/4-h/projects/horses/cloverbud-program/leader-resources. PA 4-H Horse Cloverbud Mission This educational program provides safe, fun, hands-on, developmentally appropriate learning opportunities for 4-H youth ages 5 to 7 years (as of January 1st). Using horses, this program will focus on participation as well as cooperative learning in informal settings. Summary of Differences Between -

“I Go for Independence”: Stephen Austin and Two Wars for Texan Independence

“I go for Independence”: Stephen Austin and Two Wars for Texan Independence A thesis submitted To Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by James Robert Griffin August 2021 ©Copyright All rights reserved Except for previously published materials Thesis written by James Robert Griffin B.S., Kent State University, 2019 M.A., Kent State University, 2021 Approved by Kim M. Gruenwald , Advisor Kevin Adams , Chair, Department of History Mandy Munro-Stasiuk , Interim Dean, College of Arts and Sciences TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS…………………………………………………………………...……iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS………………………………………………………………………v INTRODUCTION………………………………………………………………………………..1 CHAPTERS I. Building a Colony: Austin leads the Texans Through the Difficulty of Settling Texas….9 Early Colony……………………………………………………………………………..11 The Fredonian Rebellion…………………………………………………………………19 The Law of April 6, 1830………………………………………………………………..25 Conclusion……………………………………………………………………………….32 II. Time of Struggle: Austin Negotiates with the Conventions of 1832 and 1833………….35 Civil War of 1832………………………………………………………………………..37 The Convention of 1833…………………………………………………………………47 Austin’s Arrest…………………………………………………………………………...52 Conclusion……………………………………………………………………………….59 III. Two Wars: Austin Guides the Texans from Rebellion to Independence………………..61 Imprisonment During a Rebellion……………………………………………………….63 War is our Only Resource……………………………………………………………….70 The Second War…………………………………………………………………………78 Conclusion……………………………………………………………………………….85 -

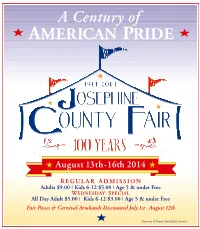

Ame R I Ca N Pr

A Century of ME R I CA N R IDE A P August 1 3th- 16th 2014 R EGULAR A DMISSION Adults $9.00 | Kids 6-12 $5.00 | Age 5 & under Free W EDNESDAY S PECIAL All Day Adult $5.00 |Kids 6-12 $3.00 | Age 5 & under Free Fair Passes & Carnival Armbands Discounted July 1st - August 1 2th Courtesy of Grants Pass Daily Courier 2 2014 Schedule of Events SUBJECT TO CHANGE 9 AM 4-H/FFA Poultry Showmanship/Conformation Show (RP) 5:30 PM Open Div. F PeeWee Swine Contest (SB) 9 AM Open Div. E Rabbit Show (PR) 5:45 PM Barrow Show Awards (SB) ADMISSION & PARKING INFORMATION: (may move to Thursday, check with superintendent) 5:30 PM FFA Beef Showmanship (JLB) CARNIVAL ARMBANDS: 9 AM -5 PM 4-H Mini-Meal/Food Prep Contest (EB) 6 PM 4-H Beef Showmanship (JLB) Special prices July 1-August 12: 10 AM Open Barrow Show (SB) 6:30-8:30 PM $20 One-day pass (reg. price $28) 1:30 PM 4-H Breeding Sheep Show (JLB) Midway Stage-Mercy $55 Four-day pass (reg. price $80) 4:30 PM FFA Swine Showmanship Show (GSR) Grandstand- Truck & Tractor Pulls, Monster Trucks 5 PM FFA Breeding Sheep and Market Sheep Show (JLB) 7 PM Butterscotch Block closes FAIR SEASON PASSES: 5 PM 4-H Swine Showmanship Show (GSR) 8:30-10 PM PM Special prices July 1-August 12: 6:30 4-H Cavy Showmanship Show (L) Midway Stage-All Night Cowboys PM PM $30 adult (reg. -

275 1. Medieval Bosnian State the Very First Inhabitants of the Bosnia

KURT 3EHAJI 3 Suad - State-legal vertical Bosnia and Herzegovina STATE -LEGAL VERTICAL BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA Assistant Professor Ph. D. Suad KURT 3EHAJI 3 The University of Political Sciences in Sarajevo Summary Bosnia and Herzegovina has millennial existence. Bosnia was first mentioned in second half of the tenth century in the work of the Byzantine emperor and writer Constantin Porfirogenet „De administrando imperio“. The Charter of Kulin Ban as of 29 August 1189 is undisputed evidence that Bosnia was an independent State. During the domination of Tvrtko I Kotromanic in 1377, Bosnia was transformed into the kingdom and became the most powerful country in the Balkans. During 1463 Bosnia was ruled by the Ottoman Empire but retained certain features of political identification, first as the Bosnian province since 1580, and afterwards as the Bosnian Vilayet since 1965. After Austro-Hungarian having arrived, Bosnia became Corpus separatum. In the Kingdom of SHS, borders of Bosnia and Herzegovina complied with the internal regionalization of the country until 1929. During the Second World War, at the First Assembly of ZAVNOBiH in Mrkonjic Grad on 25th November 1943, Bosnian sovereignty within the Yugoslav Federation was renewed. After the Yugoslav crisis, which culminated in 1991 and 1992, Yugoslavia is in dissolution and peoples and citizens of Bosnia and Herzegovina at the referendum on 29 February and 1 March 1992 voted for independence. The protagonists of greater Serbs policy could not accept such solution for Bosnia and Herzegovina and that was followed by aggression, which, after three and a half years ended by painful compromises contained in the Dayton Peace Agreement. -

Democratic Republic of Congo: Road to Political Transition

1 Democratic Republic of Congo: Road to Political Transition Dieudonné Tshiyoyo* Programme Officer Electoral and Political Processes (EPP) EISA Demographics With a total land area of 2 344 885 square kilometres that straddles the equator, the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) is the third largest country in Africa after Sudan and Algeria. It is situated right at the heart of the African continent. It shares borders by nine countries, namely Angola, Burundi, Central African Republic, Congo-Brazzaville, Rwanda, Sudan, Tanzania, Uganda and Zambia. Its population is estimated at 60 millions inhabitants and is made up of as many as 250 ethno-linguistic groups. The whole country is drained by the Congo River and its many tributaries. The second longest river in Africa and fifth longest in the world, the Congo River is second in the world after the Amazon with regard to hydroelectric potential. Brief Historical Background Established as a Belgian colony in 1908, the DRC was initially known as the ‘Congo Free State’ when it was formally attributed to King Leopold II at the Berlin Conference of 1885. In fact, in 1879 King Leopold II of Belgium commissioned Henry Morton Stanley to establish his authority over the Congo basin in order to control strategic trade routes to the West and Central Africa along the Congo River. Stanley did so by getting over 400 local chiefs to sign “treaties” transferring land ownership to the Association Internationale du Congo (AIC), a trust company belonging to Leopold II. On 30 April 1885 the King signed a decree creating the ‘Congo Free State’, thus establishing firm control over the enormous territory. -

Ernst Friedrich Sieveking

HWS_SU_Sieveking_5.10.09_END 05.10.2009 22:35 Uhr Seite 1 Aus der Reihe „Mäzene für Wissen- Ernst Friedrich Sieveking zählt zu schaft“ sind bisher erschienen: den herausragenden Persönlichkeiten der Hamburgischen Geschichte und Band 1 gehört zu den Hauptvertretern einer Die Begründer der Hamburgischen Familie, die sich um die Entwicklung Wissenschaftlichen Stiftung Hamburgs in besonderem Maß ver- dient gemacht hat. Schon früh zeigte Band 2 Ernst Friedrich Sieveking besondere Sophie Christine und Carl Heinrich Begabungen, so dass er nach dem Be- Laeisz. Eine biographische Annähe- such des Johanneums und dem Stu- rung an die Zeiten und Themen dium in Göttingen, Leipzig und Jena ihres Lebens mit der Promotion 1857 bereits im Alter von knapp 21 Jahren fertig aus- Band 3 gebildeter Jurist war. Anschließend Eduard Lorenz Lorenz-Meyer. trat er in eine renommierte Anwalts- Ein Hamburger Kaufmann und kanzlei ein, die er bald erfolgreich für Künstler viele Jahre allein führte. 1874 wurde er in die Hamburgische Bürgerschaft Band 4 und drei Jahre später in den Senat ge- Hermann Franz Matthias Mutzen- wählt. Zu seiner eigentlichen Bestim- becher. Ein Hamburger Versiche- mung fand er 1879 mit der Ernen- rungsunternehmer nung zum ersten Präsidenten des neu gegründeten Hanseatischen Ober- Band 5 landesgerichts. Bis zu seinem Tod, Die Brüder Augustus Friedrich dreißig Jahre lang, blieb er Präsident, und Gustav Adolph Vorwerk. Zwei wobei er dem Gericht insbesondere Hamburger Kaufleute als Seerechtsexperte zu hohem An- sehen verhalf. Daneben setzte er sich Band 6 engagiert für die Gründung der Ham- Albert Ballin burger Universität ein, weshalb er auch dem ersten Kuratorium der Band 7 Hamburgischen Wissenschaftlichen Ernst Friedrich Sieveking. -

Francia. Forschungen Zur Westeuropäischen

Francia. Forschungen zur Westeuropäischen Geschichte Herausgegeben vom Deutschen Historischen Institut Paris (Institut historique allemand) Band 43 (2016) Marine Fiedler: Patriotes de la Porte du Monde. L’identité politique d’une famille de négociants entre Hambourg et Bordeaux (1789–1842) Copyright Das Digitalisat wird Ihnen von perspectivia.net, der Online-Publikationsplattform der Max Weber Stiftung – Deutsche Geisteswissenschaftliche Institute im Ausland, zur Verfügung gestellt. Bitte beachten Sie, dass das Digitalisat urheberrechtlich geschützt ist. Erlaubt ist aber das Lesen, das Ausdrucken des Textes, das Herunterladen, das Speichern der Daten auf einem eigenen Datenträger soweit die vorgenannten Handlungen ausschließlich zu privaten und nicht-kommerziellen Zwecken erfolgen. Eine darüber hinausgehende unerlaubte Verwendung, Reproduktion oder Weitergabe einzelner Inhalte oder Bilder können sowohl zivil- als auch strafrechtlich verfolgt werden. Marine Fiedler PATRIOTES DE LA PORTE DU MONDE L’identité politique d’une famille de négociants entre Hambourg et Bordeaux (1789–1842) »Hambourg est une famille plus grande, et plus les bons membres d’une telle famille se multiplient, plus elle sera heureuse par elle-même. Je veux maintenant que […] tu deviennes non seulement un honnête, mais aussi un raisonnable et bon Hambour- geois1.« Par ces mots, les fils d’une famille de négociants hambourgeois, les Meyer, étaient incités par leur père le jour de leurs quatorze ans à faire preuve de patriotisme pour leur ville, comprise comme une extension de la famille bourgeoise. À la fin de l’époque moderne à Hambourg, l’identité bourgeoise était en effet fortement liée à une identité locale construite autour une tradition civique et politique spécifique. Dans »Place and Politics«, Katherine Aaslestad étudie l’évolution de cette identité locale à Hambourg entre le XVIIIe et le XIXe siècle, notamment face à l’émergence d’une identité régionale hanséatique et l’influence croissante du nationalisme cul- turel allemand à l’époque révolutionnaire et napoléonienne2. -

Yalegale in Mexico City March 4 – 9, 2017 Itinerary

YaleGALE in Mexico City March 4 – 9, 2017 Itinerary Saturday, March 4th 2017 Arrive in Mexico City and meet at the Galeria Plaza Reforma Hotel. Afternoon time to walk around and experience some indulgence at El Moro Churreria for a taste of Mexico’s churros and hot chocolate. Welcome dinner! Overnight at Galeria Plaza Reforma, a comfortable and conveniently located hotel. Sunday, March 5th 2017 Breakfast and morning meeting at the hotel. Meet your local guide at the lobby. Transfer to the city center for a guided tour of Mexico City’s historic center. Once at the Historic City Center you will visit the Templo Mayor Archaeological Site and Museum. The most important place at the main exhibition in the Museum, since 2010, is occupied by the magnificent and impressive polychrome relief depicting the goddess of the earth, Tlaltecuhtli, the largest sculptural piece of Mexica culture that has been found. The discovery took place on October 2, 2006 and can be seen in its original color from a superb restoration work. Following your visit to the Templo Mayor meet your culinary guide at the Zocalo Hub for a gastronomic adventure through the traditional flavours of Mexico, from pre-Hispanic food to contemporary culinary dishes. Explore the most important Aztec market, drink in a typical cantina and be delighted with street food. A unique and delicious experience in the Mexico City’s Historical Centre, you will eat authentic Mexican food! Following your visit you will be driven back to the Chapultepec to admire the Castle at the top of the hill. -

Celestinas Y Majas En La Obra De Goya, Alenza Y Lucas Velázquez

Celestinesca 39 (2015): 275-328 Celestinas y majas en la obra de Goya, Alenza y Lucas Velázquez Rachel Schmidt University of Calgary A pesar de que se imprimieron pocas ediciones de la Celestina de Rojas en el siglo de las luces, como resume Joseph T. Snow, la fama de la obra «se incorporó en la conciencia del país» (2000: 46), hasta que la figura de su protagonista llegó a ser un tipo que designaba mujeres ejerciendo el oficio de terceras y alcahuetas. En el sigloXVIII se solía asociar la figura de celestina con una mujer madura y astuta que guiaba a un chico joven e inocente hacia un matrimonio, le conviniera o no. Es de esta manera como José Cadalso recomendaba al «militar a la violeta» la lectura de la obra de Rojas para que el joven ingenuo aprendiera a escaparse de los designios de las «viejas zurcidoras», herederas del oficio de la Celestina (Helman 1955: 221). Luis Paret y Alcázar, en su acuarela Celestina y los enamorados (1784), ya muestra el tipo de la anciana, con nariz bulbosa y mejillas hundidas, situada en un escenario empobrecido y circundada por botellas de vino (Snow 2000: 45). La tríada de celestina, prostituta y cliente será el modelo representativo de lo que Tomás Rodríguez Rubí clasificó como el rango más bajo de la «mujer del mundo», en un ensayo publicado en Los españoles pintados por sí mismos (1843); en este estudio, una viñeta con las cabezas de tres figuras, sirve como colofón al escrito (Figura 1). Los tipos son icónicos: la Celestina «con su nariz grotesca y su barbilla grande» dirige a la chica, situada en el centro, hacia el hombre, al que quiere vender sus servicios. -

THE PORTRAYAL of the REIGN of MAXIMILIM M B GARLQTA ' 'BI THREE OONTEMPOMRX MEXICM Plabffilghts ' By- Linda E0 Haughton a Thesis

The portrayal of the reign of Maximilian and Carlota by three contemporary Mexican playwrights Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Haughton, Linda Elizabeth, 1940- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 06/10/2021 12:42:18 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/318919 THE PORTRAYAL OF THE REIGN OF MAXIMILIM MB GARLQTA ' 'BI THREE OONTEMPOMRX MEXICM PLABffilGHTS ' by- Linda E0 Haughton A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF ROMANCE LANGUAGES In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements • ' ■ i For the Degree of MASTER OF .ARTS In the Graduate College , THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 1962 STATEMENT b y au t h o r This thesis has been submitted in partial fulfillment of re quirements for an advanced degree at The University of Arizona and is deposited in The University Library to be made available to bor rowers under rules of the Library. Brief quotations from this thesis are allowable without special permission, provided that accurate acknowledgment of source is made. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this manuscript in whole or in part may be granted by the head of the major department or the Dean of the Graduate College when in their judgment the proposed use of the material is in the interests of scholarship. In all other instances, however, permission must be obtained from the author. -

Francisco De Goya

Francisco de Goya, pintor a caballo entre el clasicismo y el romanticismo que se enmarca en el periodo de la Ilustración del siglo XVIII, es una figura imprescindible de la historia del arte español. El artista vive en una constante dicotomía, puesto que trabaja para la corte y, al mismo tiempo, introduce la crítica social en su obra y se interesa por temas poco habituales, como el lado oscuro del ser humano. De esta manera, revoluciona el arte con obras maestras como La maja desnuda o La familia de Carlos IV. Su talento a la hora de plasmar a la perfección la personalidad de sus personajes en sus retratos y de captar un sentido de la luz preciso y delicado queda reflejado en sus pinturas al óleo, sus frescos, sus aguafuertes, sus litografías y sus dibujos. Esta guía estructurada y concisa te invita a descubrir todos los secretos de Francisco de Goya, desde su contexto, su biografía y las características de su obra hasta un análisis de sus trabajos principales, como la Adoración del nombre de Dios por los ángeles, El sueño de la razón produce monstruos o La maja desnuda, entre otros. Te ofrecemos las claves para: conocer la España de los siglos XVIII y XIX, que pierde importancia a nivel mundial y que se muestra reacia a toda idea liberal que provenga de fuera de sus fronteras; descubrir los detalles sobre la vida de Francisco de Goya, artista lleno de contradicciones que se convierte en una de las figuras clave de la historia del arte español; analizar una selección de sus obras clave, como La maja desnuda, la Adoración del nombre de Dios por los ángeles, El sueño de la razón produce monstruos o La familia de Carlos IV; etc. -

From “Les Types Populaires” to “Los Tipos Populares”: Nineteenth-Century Mexican Costumbrismo

Mey-Yen Moriuchi From “Les types populaires” to “Los tipos populares”: Nineteenth-Century Mexican Costumbrismo Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 12, no. 1 (Spring 2013) Citation: Mey-Yen Moriuchi, “From ‘Les types populaires’ to ‘Los tipos populares’: Nineteenth- Century Mexican Costumbrismo,” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 12, no. 1 (Spring 2013), http://www.19thc-artworldwide.org/spring13/moriuchi-nineteenth-century-mexican- costumbrismo. Published by: Association of Historians of Nineteenth-Century Art. Notes: This PDF is provided for reference purposes only and may not contain all the functionality or features of the original, online publication. Moriuchi: From “Les types populaires” to “Los tipos populares”: Nineteenth-Century Mexican Costumbrismo Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 12, no. 1 (Spring 2013) From “Les types populaires” to “Los tipos populares”: Nineteenth-Century Mexican Costumbrismo by Mey-Yen Moriuchi European albums of popular types, such as Heads of the People or Les Français peints par eux- mêmes, are familiar to most nineteenth-century art historians. What is less well known is that in the 1850s Mexican writers and artists produced their own version of such albums, Los mexicanos pintados por sí mismos (1854–55), a compilation of essays and illustrations by multiple authors that presented various popular types thought to be representative of nineteenth-century Mexico (fig. 1).[1] Los mexicanos was clearly based on its European predecessors just as it was unequivocally tied to its costumbrista origins. Fig. 1, Frontispiece, Los mexicanos pintados por sí mismos. Lithograph. From Los mexicanos pintados por sí mismos: tipos y costumbres nacionales, por varios autores. (Mexico City: Manuel Porrúa, S.A. 1974).