Intersections Between Capitalist Commodification of Thai K-Pop and Buddhist Fandoms" (2021)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kustodian Ion Lane Machines Edition 4:12

OPERATORS MANUAL FOR KUSTODIAN ION LANE MACHINES EDITION 4:12 KEGEL LLC. 1951 Longleaf Blvd. Lake Wales, FL 33859 863-734-0200 / 800-280-2695 WARRANTY KEGEL warrants that lane machines and replacement parts will be manufactured free from defects in material and workmanship under normal use and service. Except as stated below, KEGEL shall repair or replace, at its factory or authorized service station, any lane machine or replacement part (“Warranty Item”) which, within ONE YEAR after the date of installation by an authorized KEGEL Distributor, has been determined to be defective upon examination by KEGEL. In no event shall the Warranty coverage be more than twenty-four (24) months from the date of shipment from KEGEL’s factory. In the contiguous United States, the bowling center or end-user will be responsible for requesting Warranty Items from KEGEL and must return Warranty Items directly to KEGEL, following the required procedures. KEGEL will pay reasonable freight charges to deliver and receive Warranty Items from the bowling center. KEGEL will not be responsible for any “expedited” shipping charges. Customer will be invoiced for Warranty Items that are not promptly returned per the required procedures. Outside the contiguous United States, the bowling center or end-user will be responsible for requesting Warranty Items from the DISTRIBUTOR and must return Warranty Items directly to the DISTRIBUTOR, following the required procedures. KEGEL will compensate the DISTRIBUTOR for reasonable freight charges to deliver and receive the Warranty Items from bowling center and to return them to KEGEL. Under no circumstances will KEGEL be responsible for any “expedited” shipping charges or taxes and duties. -

Chiangmai General Information

Chiangmai general information Le Méridien Hotel 108 Chang Klan Road, Tambol Chang Klan, Muang, Chiang Mai, 50100, Thailand Tel +6653-253-666 ✉ [email protected] How to Get to Chiang Mai from Bangkok ● By Air (1 hr from Bangkok) Domestic airlines (Thai Airways International, Bangkok Airways, Air Asia, Orient Thai Airlines and Nok Air ) operate several daily flights between Bangkok and Chiang Mai. A one-way flight takes about one hour. There are also regular domestic flights between Chiang Mai and other major cities in Thailand and international flights to and from some major Asian destinations ● By Bus (10-11 hrs from Bangkok) Several ordinary and air-conditioned buses leaving daily from Bangkok's Northern Bus Terminal (also known as Mo Chit) on Kamphaeng Phet 2 Road. ● By Rail Express and rapid trains leave for Chiang Mai from Hualamphong Station several times daily and the trip takes about 11-12 hours for express trains. Chiangmai average temperature in September (°F) (°C) Suggested attire outside of Meeting Lightweight, breathable clothes as it will be High 90° 32° warm and humid during the day. Please bring a light jacket for evenings, and umbrella/raincoat Low 70° 21° in case of rain. Thai Currency = Baht Currency exchange rate 1.00 USD = 35.00 THB Money changer ● Chiang Mai airport Banking Currency Exchange counters are opposite the international arrival lounge ● Chiangmai city ATMs and exchange bureaux in most tourist places Chiang Mai in Northern Thailand lives up to its nickname “The Rose of the North”. The city is packed full of natural wonder, adventure, intrigue, romance, and history; making it a must-visit location in Asia. -

LARP Rules for the Dystopia Rising Universe Intended for Use At

LARP Rules for the Dystopia Rising Universe Intended for use at licensed Dystopia Rising events. All rights reserved. 1 Dead-icated to my parents for not seeing gaming as the devil incarnate, to my friends for the support and encouragement to actually get my pet project going, George Romero for redefining the zombie genre, and to Gary Gygax and Dave Arneson for teaching me that the art of telling a story lives forever. Lastly to Ashley, for being my push when I was unsure. Without you this game would have never been anything more than ideas in my head and talk around a hookah. Original World Creation Michael Pucci Executive Producer Ashley Zdeb Contributing Writers Joshua Demers, Megan Jaffe, R.M. Sean Benjamin Jaffe, Mike Malecki, Liam Neary, Ben Przybylinski, Matthew Volk, Matt Wallace, Peter Woodworth Contributing Artists Cryssy Cheung, Zach Herschberger, Joshua Brain Jaffe, Peter Moschel Johnson, Jennifer Lazaroff, Richard Sampson, Andrew Scott, Matthew Volk Layout and Design Matthew Volk Cover Design Joshua Brain Jaffe Copyright 2009-2016 Dystopia Rising LLC All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form by any means, mechanical, electronic, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without written permission of Dystopia Rising LLC. All illustrations and images are property of Eschaton Media or used under the allowed rights of public domain. Dystopia Rising is a registered trademark of Michael Pucci and may not be used without written permission of Michael Pucci. -

Appendix 8: Damages Caused by Natural Disasters

Building Disaster and Climate Resilient Cities in ASEAN Draft Finnal Report APPENDIX 8: DAMAGES CAUSED BY NATURAL DISASTERS A8.1 Flood & Typhoon Table A8.1.1 Record of Flood & Typhoon (Cambodia) Place Date Damage Cambodia Flood Aug 1999 The flash floods, triggered by torrential rains during the first week of August, caused significant damage in the provinces of Sihanoukville, Koh Kong and Kam Pot. As of 10 August, four people were killed, some 8,000 people were left homeless, and 200 meters of railroads were washed away. More than 12,000 hectares of rice paddies were flooded in Kam Pot province alone. Floods Nov 1999 Continued torrential rains during October and early November caused flash floods and affected five southern provinces: Takeo, Kandal, Kampong Speu, Phnom Penh Municipality and Pursat. The report indicates that the floods affected 21,334 families and around 9,900 ha of rice field. IFRC's situation report dated 9 November stated that 3,561 houses are damaged/destroyed. So far, there has been no report of casualties. Flood Aug 2000 The second floods has caused serious damages on provinces in the North, the East and the South, especially in Takeo Province. Three provinces along Mekong River (Stung Treng, Kratie and Kompong Cham) and Municipality of Phnom Penh have declared the state of emergency. 121,000 families have been affected, more than 170 people were killed, and some $10 million in rice crops has been destroyed. Immediate needs include food, shelter, and the repair or replacement of homes, household items, and sanitation facilities as water levels in the Delta continue to fall. -

The Significance of Khruba Sriwichai 'S Role in Northern Thai Buddhism : His Sacred Biography , Meditation Practice and Influence

THE SIGNIFICANCE OF KHRUBA SRIWICHAI 'S ROLE IN NORTHERN THAI BUDDHISM : HIS SACRED BIOGRAPHY , MEDITATION PRACTICE AND INFLUENCE ISARA TREESAHAKIAT Thesis submitted for the degree of Master of Arts in Religious Studies, University of Otago, Dunedin, New Zealand, 29 April 2011 Table of Contents ABSTRACT ................................................................................................................ i ACKNOWLEDGEMENT ............................................................................................ iii INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................... 1 CHAPTER ONE : A LITERATURE REVIEW OF THAI AND ENGLISH MATERIALS ON KHRUBA SRIWICHAI ............................................................................................... 6 Introduction .......................................................................................................... 6 1.1 The definitions of khruba and ton bun ........................................................... 7 1.2 The belief in ton bun , millennialism, and bodhisatta .................................. 11 1.3 The association between ton bun and political authority ............................. 14 1.4 Ton bun , Buddhist revival and construction of sacred space ....................... 17 1.5 The fundamental theory of charisma ........................................................... 19 1.6 The theory of sacred biography and the framework for conceptualizing the history of the monks in Thailand ...................................................................... -

China's Year in Review

2017 China's Year in Review Follow China Intercontinental Press Us on Advertising Hotline WeChat Now 城市漫步珠 国内统一刊号: 三角英文版 that's guangzhou that's shenzhen CN 11-5234/GO JANUARY 2018 01月份 that’s PRD 《城市漫步》珠江三角洲 英文月刊 主管单位 : 中华人民共和国国务院新闻办公室 Supervised by the State Council Information Office of the People's Republic of China 主办单位 : 五洲传播出版社 地址 : 北京西城月坛北街 26 号恒华国际商务中心南楼 11 层文化交流中心 11th Floor South Building, Henghua lnternational Business Center, 26 Yuetan North Street, Xicheng District, Beijing http://www.cicc.org.cn 社长 President: 陈陆军 Chen Lujun 期刊部负责人 Supervisor of Magazine Department: 邓锦辉 Deng Jinhui 编辑 Editor: 朱莉莉 Zhu Lili 发行 Circulation: 李若琳 Li Ruolin Senior Digital Editor Matthew Bossons Shenzhen Editor Adam Robbins Guangzhou Editor Daniel Plafker Shenzhen Digital Editor Bailey Hu Senior Staff Writer Tristin Zhang Digital Editor Katrina Shi National Arts Editor Erica Martin Contributors Ned Kelly, Betty Richardson, Lena Gidwani, Dr. Adam Koh, Mia Li, Katrina Shi, Dominic Ngai, Erica Martin, Dominique Wong, Bryan Grogan, Kheng Swe Lim, Paul Barresi, Sky Gidge HK FOCUS MEDIA Shanghai (Head Office) 上海和舟广告有限公司 上海市蒙自路 169 号智造局 2 号楼 305-306 室 邮政编码 : 200023 Room 305-306, Building 2, No.169 Mengzi Lu, Shanghai 200023 电话 : 传真 : Guangzhou 上海和舟广告有限公司广州分公司 广州市麓苑路 42 号大院 2 号楼 610 室 邮政编码 : 510095 Rm 610, No. 2 Building, Area 42, Luyuan Lu, Guangzhou 510095 电话 : 020-8358 6125 传真 : 020-8357 3859 - 816 Shenzhen 深圳联络处 深圳市福田区彩田路星河世纪大厦 C1-1303 C1-1303, Galaxy Century Building, Caitian Lu, Futian District, Shenzhen 电话 : 0755-8623 3220 传真 : 0755-6406 8538 Beijing 北京联络处 北京市东城区东直门外大街 48 号东方银座 C 座 G9 室 邮政编码 : 100027 9G, Block C, Ginza Mall, No. -

Tour Itinerary

GEEO ITINERARY THAILAND – Winter Day 1: Bangkok Arrive at any time. Arrive in Bangkok at any time. Check into our hotel and enjoy the city. Check the notice boards or ask at reception for the exact time and location of the group meeting, typically 6:00 p.m. or 7:00 p.m. After the meeting, you might consider heading out for a meal in a nearby local restaurant to further get to know your tour leader and travel companions. Please make every effort to arrive on time for this welcome meeting. If you are delayed and will arrive late, please inform us. Your tour leader will then leave you a message at the front desk informing you of where and when to meet up. Day 2: Bangkok (B) Guided longboat tour of Bangkok's klongs and Wat Po. Opt to visit Grand Palace and National Museum. You have free time this afternoon to enjoy this bustling city. We begin the day with a guided visit to Wat Po. Immerse yourself in Thai Buddhist culture and visit the famous giant 46m (151ft) reclining Buddha, covered in gold leaf. Relax with a traditional Thai massage at the country’s leading school of massage at Wat Po. We then have a Klong Riverboat tour. Travel by longtail boat on the busy Chao Phraya River. Go through the smaller klongs (canals) to see skyscrapers, temples, and shops in the distance, and the densely populated waterfront settlements up close. The afternoon is free for you to enjoy this bustling metropolis. Stroll through one of Bangkok’s many malls and open-air markets, and pick up something if you'd like. -

Digital Transformation Stories

Huawei Enterprise e.huawei.com Yue B No. 13154 09/2017 ICT INSIGHTS Yang Xiaoling, “The CPIC digital strategy aims to innovate business models by leveraging technical advantages. CPIC is walking the road Vice President and to digital transformation, and we will continue working with Huawei to provide customers with convenient, high-quality Chief Digital Officer, CPIC { insurance services.” “We decided to build an enterprise private cloud platform and use cloud infrastructure to support our Li Zhihong, core business systems such as ERP and CRM. Huawei has provided us with a series of ICT infrastructure Information Management Department, solutions, such as FusionCube, that fully meet our business development needs and conform to our Digital COFCO Coca-Cola Beverages Ltd. { ICT transformation strategy. We are looking forward to further cooperation with Huawei.” Transformation “In terms of products and solutions, Huawei responds to customer requirements very fast and is highly efficient in terms of product Qi Wei, optimization. After the feedback is sent to R&D, measures are quickly taken to create an optimized version. At the same time, in the cooperation IT Planning Director, Organization process, Dongfeng also acquired valuable management experience from many of Huawei’s outstanding projects. We now use this knowledge Information Department, Dongfeng Motor Group Stories { in our own internal project processes. That’s why we believe the benefits we reaped from cooperating with Huawei are huge.” in the New ICT Era Liu Jianming, “Digital transformation paves the way for more robust Smart Grids, making our life better. Deputy Director of the Power Informatization Study Committee, Huawei is willing and expected to play a bigger role in digital transformation of electric power China Society for Electrical Engineering { systems in all countries and regions across the globe.” “Huawei had clearly done its homework and demonstrated a deep understanding of what we were doing with Hadoop. -

April 2018 04月份

Follow China Intercontinental Press Us on Advertising Hotline WeChat Now 城市漫步珠 国内统一刊号: 三角英文版 that's guangzhou that's shenzhen CN 11-5234/GO APRIL 2018 04月份 that’s PRD 《城市漫步》珠江三角洲 英文月刊 主管单位 : 中华人民共和国国务院新闻办公室 Supervised by the State Council Information Office of the People's Republic of China 主办单位 : 五洲传播出版社 地址 : 北京西城月坛北街 26 号恒华国际商务中心南楼 11 层文化交流中心 11th Floor South Building, Henghua lnternational Business Center, 26 Yuetan North Street, Xicheng District, Beijing http://www.cicc.org.cn 社长 President: 陈陆军 Chen Lujun 期刊部负责人 Supervisor of Magazine Department: 邓锦辉 Deng Jinhui 编辑 Editor: 朱莉莉 Zhu Lili 发行 Circulation: 李若琳 Li Ruolin Editor-in-Chief Matthew Bossons Shenzhen Editor Adam Robbins Guangzhou Editor Daniel Plafker Shenzhen Digital Editor Bailey Hu Senior Staff Writer Tristin Zhang Digital Editor Katrina Shi National Arts Editor Erica Martin Contributors Lena Gidwani, Bryan Grogan, Mia Li, Kheng Swe Lim, Benjamin Lipschitz, Erica Martin, Noelle Mateer, Dominic Ngai, Katrina Shi, Alexandria Williams, Dominique Wong HK FOCUS MEDIA Shanghai (Head Office) 上海和舟广告有限公司 上海市蒙自路 169 号智造局 2 号楼 305-306 室 邮政编码 : 200023 Room 305-306, Building 2, No.169 Mengzi Lu, Shanghai 200023 电话 : 传真 : Guangzhou 上海和舟广告有限公司广州分公司 广州市麓苑路 42 号大院 2 号楼 610 室 邮政编码 : 510095 Rm 610, No. 2 Building, Area 42, Luyuan Lu, Guangzhou 510095 电话 : 020-8358 6125 传真 : 020-8357 3859 - 816 Shenzhen 深圳联络处 深圳市福田区彩田路星河世纪大厦 C1-1303 C1-1303, Galaxy Century Building, Caitian Lu, Futian District, Shenzhen 电话 : 0755-8623 3220 传真 : 0755-6406 8538 Beijing 北京联络处 北京市东城区东直门外大街 48 号东方银座 C 座 G9 室 邮政编码 -

Asia & Indochina

2019 - 2020 ASIA & INDOCHINA VIETNAM | CAMBODIA | LAOS | MYANMAR | THAILAND MALAYSIA | BORNEO | PHILIPPINES | BALI | SINGAPORE www.exoticholidays.co.nz www.exotictours.com.au 0508 396 842 1800 316 379 0508 396 842 | exoticholidays.co.nz | 1800 316 379 | www.exotictours.com.au All Prices indicated are per person Twin share for low season 1 WELCOME CONTENTS EXOTIC HOLIDAYS Multi-Award winning Specialist Tour Operators for Asia, India & Sub-Continent, Middle East & Europe Exotic Holidays are passionate about travel and about providing a unique and extraordinary travel experience. Enthusiastic and accomplished travellers ourselves, Team Exotic recognises no two holidays are the same and hence, provide expertise in tailor-made individual and group holidays, offering practical advice based on personal travel experiences, professional approach and seamless travel arrangements. We offer an extensive product range varying from economy hotels to the most exotic hotels, spas and resorts, private tours and luxurious rail journeys. With the expertise to design customised itineraries giving total fl exibility and the ability to arrange private transfers, excursions and organized tours. All our packages can be customised to suit any requirements. Our programs are designed to ensure you get the most out of your trip. Let Exotic Holidays take you to the less frequented places to experience the sights, monuments and tourist attractions while experiencing local life. Walk with the people, stroll through village markets, share in the cooking and eating of -

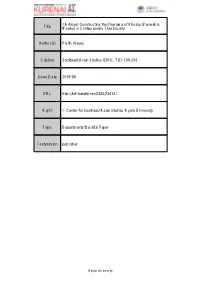

<Articles>Constructing the Charisma of Khruba (Venerable Monks)

<Articles>Constructing the Charisma of Khruba (Venerable Title Monks) in Contemporary Thai Society Author(s) Pisith, Nasee Citation Southeast Asian Studies (2018), 7(2): 199-236 Issue Date 2018-08 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2433/234131 Right © Center for Southeast Asian Studies, Kyoto University Type Departmental Bulletin Paper Textversion publisher Kyoto University Southeast Asian Studies, Vol. 49, No. 2, September 2011 Constructing the Charisma of Khruba (Venerable Monks) in Contemporary Thai Society Pisith Nasee* Khruba (venerable monks) have consistently played a meaningful role in local Bud- dhist communities of Northern Thai culture for generations. While today’s khruba continue to represent themselves as followers of Khruba Siwichai and Lan Na Bud- dhism, in fact over the past three decades they have flourished by adopting hetero- geneous beliefs and practices in the context of declining influence of the sangha and popular Buddhism. In order to respond to social and cultural transformations and to fit in with different expectations of people, modern khruba construct charisma through different practices besides the obvious strictness in dhamma used to explain the source of khruba’s charisma in Lan Na Buddhist history. The ability to integrate local Buddhist traditions with the spirit of capitalism-consumerism and gain a large number of followers demonstrates that khruba is still a meaningful concept that plays a crucial role in modern Buddhist society, particularly in Thailand. By employ- ing concepts of charisma, production of translocalities, and popular Buddhism and prosperity religion, it can be argued that khruba is steeped in local knowledge, yet the concept has never been linear and static. -

Colorado Journal of Asian Studies, Volume 5, Issue 1

COLORADO JOURNAL OF ASIAN STUDIES Volume 5, Issue 1 (Summer 2016) 1. Comparative Cultural Trauma: Post-Traumatic Processing of the Chinese Cultural Revolution and the Cambodian Revolution Carla Ho 10. Internet Culture in South Korea: Changes in Social Interactions and the Well-Being of Citizens Monica Mikkelsen 21. Relationality in Female Hindu Renunciation as Told through the Life Story of Swāmī Amritanandā Gīdī Morgan Sweeney 47. Operating in the Shadow of Nationalism: Egyptian Feminism in the Early Twentieth Century Jordan Witt 60. The Appeal of K-pop: International Appeal and Online Fan Behavior Zesha Vang Colorado Journal of Asian Studies Volume 5, Issue 1 (Summer 2016) Center for Asian Studies University of Colorado Boulder Page i 1424 Broadway, Boulder, CO 80309 Colorado Journal of Asian Studies Volume 5, Issue 1 (Summer 2016) The Colorado Journal of Asian Studies is an undergraduate journal published by the Center for Asian Studies at the University of Colorado at Boulder. Each year we highlight outstanding theses from our graduating seniors in the Asian Studies major. EXECUTIVE BOARD AY 2016-2017 Tim Oakes, Director Carla Jones, Interim Director, Spring (Anthropology, Southeast Asia) Colleen Berry (Associate Director/Instructor) Aun Ali (Religious Studies, West Asia/Middle East) Chris Hammons (Anthropology, Indonesia) Sungyun Lim (History, Korea, East Asia Terry Kleeman (Asian Languages & Civilizations, China, Daoism) RoBert McNown (Economics) Meg Moritz (College of Media Communication and Information) Ex-Officio Larry Bell (Office of International Education) Manuel Laguna (Leeds School of Business) Xiang Li (University Libraries, East Asia-China) Adam LisBon (University Libraries, East Asia-Japan, Korea) Lynn Parisi (Teaching about East Asia) Danielle Rocheleau Salaz (CAS Executive Director) CURRICULUM COMMITTEE AY 2016-2017 Colleen Berry, Chair Aun Ali (Religious Studies, West Asia/Middle East) Jackson Barnett (Student Representative) Kathryn GoldfarB (Anthropology, East Asia-Japan) Terry Kleeman (AL&L; Religious Studies.