Dvoràk STABAT MATER

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EMR 12669 Schubert Stabat Mater MF

Stabat Mater Wind Band / Concert Band / Harmonie / Blasorchester / Fanfare Arr.: John Glenesk Mortimer Franz Schubert EMR 12669 st 1 Score 2 1 Trombone + st nd 4 1 Flute 2 2 Trombone + nd 4 2 Flute 1 Bass Trombone + 1 Oboe (optional) 2 Baritone + 1 Bassoon (optional) 2 E Bass 1 E Clarinet (optional) 2 B Bass 5 1st B Clarinet 2 Tuba 4 2nd B Clarinet 1 String Bass (optional) 4 3rd B Clarinet 1 Piano Reduction (optional) 1 B Bass Clarinet (optional) 1 B Soprano Saxophone (optional) 2 1st E Alto Saxophone Special Parts Fanfare Parts 2 2nd E Alto Saxophone 1 1st B Trombone 2 1st Flugelhorn 2 B Tenor Saxophone 1 2nd B Trombone 2 2nd Flugelhorn 1 E Baritone Saxophone (optional) 1 B Bass Trombone 2 3rd Flugelhorn 1 E Trumpet / Cornet (optional) 1 B Baritone 3 1st B Trumpet / Cornet 1 E Tuba 3 2nd B Trumpet / Cornet 1 B Tuba 3 3rd B Trumpet / Cornet 2 1st F & E Horn 2 2nd F & E Horn 2 3rd F & E Horn Print & Listen Drucken & Anhören Imprimer & Ecouter≤ www.reift.ch Route du Golf 150 CH-3963 Crans-Montana (Switzerland) Tel. +41 (0) 27 483 12 00 Fax +41 (0) 27 483 42 43 E-Mail : [email protected] www.reift.ch Recorded on CD - Auf CD aufgenommen - Enregistré sur CD | Franz Schubert Photocopying Stabat Mater is illegal! Arr.: John Glenesk Mortimer 34 5 6 78 Largo q = 50 1st Flute fp p sost. fp f 2nd Flute fp p sost. fp f Oboe fp p sost. -

82890-5 First Book Dvorak Jb.Indd 3 8/22/18 12:09 PM Pastorale from Czech Suite Op

Contents Author’s Note i v Pastorale 1 Kyrie 2 Symphony No. 9, Mvt. IV (Theme) 3 Silhouettes 4 String Quintet No. 12 5 Prague Waltzes 6 Romance 7 Symphony No. 8, Mvt. IV (Theme) 8 Waltz 9 Romantic Pieces 1 0 Symphony No. 9, Mvt. I (Theme) 1 1 Song to the Moon 1 2 In a Ring! 1 4 Bacchanale 1 6 Songs My Mother Taught Me 1 7 Mazurka 1 8 Cypresses 2 0 Cello Concerto 2 1 Grandpa Dances with Grandma 2 2 Mazurka 2 4 Stabat Mater 2 6 The Question 2 7 Chorus of the Water Nymphs 2 8 Capriccio 2 9 The Water Goblin 3 0 Ballade 3 1 Serenade for Strings 3 2 Dumka 3 3 The Noon Witch 3 4 Symphony No. 9, Mvt. II (Largo) 3 6 Serenade for Wind Instruments 3 7 Slavonic Dances 3 8 Violin Concerto Mvt. I 3 9 Violin Concerto Mvt. II 4 0 Six Piano Pieces 4 2 Humoresque 4 4 82890-5 First Book Dvorak jb.indd 3 8/22/18 12:09 PM Pastorale from Czech Suite Op. 39 A pastorale is a musical composition intended to evoke images of nature and the countryside. This rustic melody is supported by a static left hand playing an open fifth (C–G). The effect is known as a drone and is reminiscent of old folk instruments. 1 82890-5 First Book Dvorak jb.indd 1 8/22/18 12:09 PM Kyrie from Mass Op. 86 The Kyrie is the traditional first movement of the Mass. -

A Conductor's Analysis of Amaral Vieira's Stabat Mater, Op.240: an Approach Between Music and Rhetoric Vladimir A

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2005 A conductor's analysis of Amaral Vieira's Stabat Mater, op.240: an approach between music and rhetoric Vladimir A. Pereira Silva Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Pereira Silva, Vladimir A., "A conductor's analysis of Amaral Vieira's Stabat Mater, op.240: an approach between music and rhetoric" (2005). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3618. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3618 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. A CONDUCTOR’S ANALYSIS OF AMARAL VIEIRA’S STABAT MATER, OP. 240: AN APPROACH BETWEEN MUSIC AND RHETORIC A Monograph Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The School of Music by Vladimir A. Pereira Silva B.M.E., Universidade Federal da Paraíba, 1992 M. Mus., Universidade Federal da Bahia, 1999 May, 2005 © Copyright 2005 Vladimir A. Pereira Silva All rights reserved ii In principio erat Verbum et Verbum erat apud Deum et Deus erat Verbum. Evangelium Secundum Iohannem, Caput 1:1 iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This dissertation would have not been possible without the support of many people and institutions throughout the last several years, and I would like to thank them all for a great graduate school experience. -

B Ach Cantatas for Christmas Gardiner

Bach Cantatas for Christmas Gardiner 1 Bach Cantatas for Christmas Gardiner 2 The Bach Cantata Pilgrimage On Christmas Day 1999 a unique celebration of the new Millennium began in the Herderkirche in Weimar, Germany: the Monteverdi Choir and English Baroque Soloists under the direction of Sir John Eliot Gardiner set out to perform all Johann Sebastian Bach’s surviving church cantatas in the course of the year 2000, the 250th anniversary of Bach’s death. The cantatas were performed on the liturgical feasts for which they were composed, in a year-long musical pilgrimage encompassing some of the most beautiful churches throughout Europe (including many where Bach himself performed) and culminating in three concerts in New York over the Christmas festivities at the end of the millennial year. These recordings of cantatas for the Christmas season were made at the beginning and end of the Pilgrimage. 3 Johann Sebastian Bach 1685-1750 Cantatas for Christmas and New Year Pages 5-13 CD 1 For Christmas Day 63 / 191 14-24 CD 2 For Christmas Day 91 / 110 For the Second Day of Christmas 121 / 40 25-38 CD 3 For the Second Day of Christmas 57 For the Third Day of Christmas 64 / 151 / 133 39-50 CD 4 For the Sunday after Christmas Motet 225 / 152 / 122 / 28 For New Year’s Day 190 51-62 CD 5 For New Year’s Day 143 / 41 / 16 / 171 63-73 CD 6 For the Sunday after New Year 153 / 58 For Epiphany 65 / 123 The Monteverdi Choir The English Baroque Soloists John Eliot Gardiner Live recordings from the Bach Cantata Pilgrimage Weimar / New York / Berlin / Leipzig 1999-2000 4 For Christmas Day Claron McFadden soprano Bernarda Fink alto Christoph Genz tenor Dietrich Henschel bass The Monteverdi Choir The English Baroque Soloists 1 John Eliot Gardiner Herderkirche, Weimar, 25 December 1999 « Contents page 5 CD1 40:15 For Christmas Day 26:28 Christen, ätzet diesen Tag BWV 63 1 (4:48) 1. -

EMR 12386 Stabat Mater WB

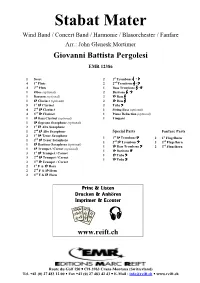

Stabat Mater Wind Band / Concert Band / Harmonie / Blasorchester / Fanfare Arr.: John Glenesk Mortimer Giovanni Battista Pergolesi EMR 12386 st 1 Score 2 1 Trombone + st nd 4 1 Flute 2 2 Trombone + nd 4 2 Flute 1 Bass Trombone + 1 Oboe (optional) 2 Baritone + 1 Bassoon (optional) 2 E Bass 1 E Clarinet (optional) 2 B Bass 5 1st B Clarinet 2 Tuba 4 2nd B Clarinet 1 String Bass (optional) 4 3rd B Clarinet 1 Piano Reduction (optional) 1 B Bass Clarinet (optional) 1 Timpani 1 B Soprano Saxophone (optional) st 2 1 E Alto Saxophone 1 2nd E Alto Saxophone Special Parts Fanfare Parts st 2 1 B Tenor Saxophone 1 1st B Trombone 2 1st Flugelhorn 1 2nd B Tenor Saxophone 1 2nd B Trombone 2 2nd Flugelhorn 1 E Baritone Saxophone (optional) 1 B Bass Trombone 2 3rd Flugelhorn 1 E Trumpet / Cornet (optional) 1 B Baritone 3 1st B Trumpet / Cornet 1 E Tuba 3 2nd B Trumpet / Cornet 1 B Tuba 3 3rd B Trumpet / Cornet 2 1st F & E Horn 2 2nd F & E Horn 2 3rd F & E Horn Print & Listen Drucken & Anhören Imprimer & Ecouter≤ www.reift.ch Route du Golf 150 CH-3963 Crans-Montana (Switzerland) Tel. +41 (0) 27 483 12 00 Fax +41 (0) 27 483 42 43 E-Mail : [email protected] www.reift.ch DISCOGRAPHY Baroque Splendour Volume 2 Track Titel / Title Time N° EMR N° EMR N° (Komponist / Composer) Blasorchester Brass Band Concert Band 1 Rondeau (Les Indes Galantes) (Rameau) 1’51 EMR 12220 EMR 32124 2 Le Basque (Marais) 2’24 EMR 12611 EMR 32125 3 Tambourin (Dardanus) (Rameau) 2’29 EMR 12213 EMR 32126 4 Marche Royale (Lully) 2’18 EMR 12226 EMR 9855 5 Symphonies pour -

Brahms Beethoven

Saturday 18 November 2017 at 7pm All Saints’ Church Lovelace Road West Dulwich SE21 8JY Beethoven Violin Concerto in D Soloist: Patrick Rafter Brahms Ein deutsches Requiem Dulwich Symphony Chorus Ruth Holton (soprano) Jonny Davies (baritone) Leigh O’Hara Conductor Paula Tysall Leader £12/£10 (concessions) under 16s free Interval collection for St Christopher’s Hospice DSO is a registered charity. Charity no. 1100857 Violin Concerto in D Major, Op. 61 (1806) Ludwig van Beethoven i. Allegro ma non troppo ii. Larghetto iii. Rondo Allegro By the time he wrote his only violin concerto, Joseph Joachim, later a close collaborator of Brahms. Beethoven had been living in Vienna for fourteen years. Under Mendelssohn’s baton, the twelve-year-old His hearing had already deteriorated but, in spite of Joachim elicited frenetic applause for his sensation this, the works composed during this, his middle performance before a London audience in 1844. period, show a new generosity of scale, increased From its courtly opening theme to its lively final emotional weight and a spirit of momentum. movement, the concerto is a triumph. Four soft timpani The only violin concerto after Mozart’s five of 1775 strokes open the piece, forming the foundation of the and Mendelssohn’s of 1844 which is still regularly first movement, one of the longest in all Beethoven’s performed, Beethoven’s concerto harnesses classic works, including the symphonies. The initial statement elements of the form while maximizing their dramatic of the main theme is reshaped by the violin. The second force. For all its modern totemic status, its early movement is a peaceful larghetto with two themes and reception was inauspicious. -

A Critical Study of Five Reconstructions of Bach's Markuspassion BWV 247 with Particular Reference to the Parody Technique

A critical study of five reconstructions of Bach’s Markuspassion BWV 247 with particular reference to the parody technique Paula Fourie Supervisor: Professor John Hinch Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree MMus Department of Music University of Pretoria November 2010 © University of Pretoria Acknowledgements I would like to thank the following people for their part in this dissertation: • Professor John Hinch for his guidance and supervision • Johann van der Sandt for guiding me to this topic and for providing scores and recordings of several of the reconstructions under discussion • Isobel Rycroft from the UP music library for her unwavering help in locating information sources • My parents who have shown that learning is a life-long quest • Etienne, for his patience and assistance with proofreading ©© Abstract A part of Johann Sebastian Bach’s musical duties in Leipzig was to present an annual setting of the passion for Good Friday Vespers. One such work was the Markuspassion, performed in 1731. Although the score of this companion work to the Matthäuspassion and Johannespassion has been lost, the original text of the Markuspassion is extant. Bach frequently made use of the parody technique in his compositions. This practice consisted of adapting existing music to a new text that was based on the rhyme scheme of the original one, resulting in two compositions essentially sung to the same music, barring a number of enforced changes. This particular feature of Bach’s compositional technique makes it possible that the lost music originally contained in the Markuspassion could be discovered within his oeuvre. In the late 19th century, Bach scholars began to research the possibility of reconstructing the Markuspassion, recognizing that it may have contained music parodied from other compositions basing, to a large extent, their research on textual comparison. -

Antonín Dvorák • Requiem

Antonín Dvorˇák • Requiem Ilse Eerens – Bernarda Fink – Maximilian Schmitt – Nathan Berg Collegium Vocale Gent – Royal Flemish Philharmonic Philippe Herreweghe Tracklist – p. 5 English – p. 8 Français – p. 13 Deutsch – p. 19 Nederlands – p. 25 Sung Texts – p. 30 Antonín Dvorˇák (1841-1904) Requiem, Op. 89 Ilse Eerens soprano Bernarda Fink alto Maximilian Schmitt tenor Nathan Berg bass Collegium Vocale Gent Royal Flemish Philharmonic Philippe Herreweghe Recording: April 28-30, 2014, deSingel, Antwerp — Sound Engineer: Markus Heiland (Tritonus) — Editing: Markus Heiland & Andreas Neubronner (Tritonus) — Recording Producer, Mastering: Andreas Neubronner (Tritonus) — Liner Notes: Tom Janssens — Cover picture: photo Michel Dubois (Courtesy Dubois Friedland) — Photographs Philippe Herreweghe: Michiel Hendryckx — Design: Casier/Fieuws — Executive Producer: Aliénor Mahy MENU CD 1 INTROITUS [1] Requiem æternam – Kyrie eleison (Soli and Chorus)........................................................10’44 GRADUALE [2] Requiem æternam (Soprano and Chorus)......................................................................04’38 SEQUENTIA [3] Dies iræ (Chorus).......................................................................................................02’28 [4] Tuba mirum (Soli and Chorus) ....................................................................................08’35 [5] Quid sum miser (Soli and Chorus) ...............................................................................06’02 [6] Recordare, Jesu pie (Soli) .............................................................................................07’03 -

Download Booklet

552139-40bk VBO Dvorak 16/8/06 9:48 PM Page 8 CD1 1 Carnival Overture, Op. 92 . 9:29 2 Humoresques, Op. 101 No. 7 Poco lento e grazioso in G flat major . 2:51 3 String Quartet No. 12 in F major, Op. 96 ‘American’ III. Molto vivace . 4:01 4 Symphony No. 8 in G major, Op. 88 III. Allegretto grazioso – Molto vivace . 5:45 5 7 Gipsy Melodies ‘Zigeunerlieder’ – song collection, Op. 55 No. 4 Songs my mother taught me . 2:47 6 Serenade for Strings in E major, Op.22 I. Moderato . 4:10 7 Slavonic Dances, Op. 46 No. 2 in E minor . 4:40 8 Piano Trio in F minor ‘Dumky’, Op. 90 III. Andante – Vivace non troppo . 5:56 9 Symphony No. 7 in D minor, Op. 70 III. Scherzo: Vivace – Poco meno messo . 7:47 0 Violin Sonatina in G major, Op. 100 II. Larghetto . 4:33 ! Slavonic Dances, Op. 72 No. 2 in E minor . 5:29 @ Rusalka, Op. 114 O, Silver Moon . 5:52 # The Noon Witch . 13:04 Total Timing . 77:10 CD2 1 Slavonic Dances, Op. 46 No. 1 in C major . 3:46 2 Stabat Mater, Op. 58 Fac ut portem Christi mortem . 5:13 3 Serenade for Wind, Op.44 I. Moderato, quasi marcia . 3:51 4 Cello Concerto in B minor, Op. 104 II. Adagio ma non troppo . 12:29 5 Piano Quintet in A major, Op. 81 III. Scherzo (Furiant) – Molto vivace . 4:06 6 Czech Suite, Op. 39 II. Polka . 4:49 7 Legends, Op. -

Thursday Playlist

February 14, 2019: (Full-page version) Close Window “Imagination creates reality.” —Richard Wagner Start Buy CD Stock Program Composer Title Performers Record Label Barcode Time online Number Sleepers, 00:01 Buy Now! Humperdinck Overture ~ Hansel and Gretel Symphony Nova Scotia/Tintner CBC 5167 059582516720 Awake! 00:10 Buy Now! Mozart Piano Concerto No. 25 in C, K. 503 Argerich/Orchestra Mozart/Abbado DG 479 1033 028947910336 00:41 Buy Now! Prokofiev Romeo and Juliet: Suite No. 3, Op. 101 Suisse Romande Orchestra/Jordan Erato 45817 022924581724 01:00 Buy Now! Sibelius Night Ride and Sunrise, Op. 55 Philharmonia Orchestra/Rattle EMI 47006 N/A London 01:16 Buy Now! Mendelssohn Octet in E flat, Op. 20 London Concertante 0722 5060055390124 Concertante 01:48 Buy Now! Vivaldi Concerto in A minor for 2 Violins, Op. 3 No. 8 I Musici Philips 412 128 02894121282 02:01 Buy Now! Delibes Les filles de Cadix Fleming/Philharmonia/Lang-Lessing Decca B0019033 0289478510703 02:05 Buy Now! Paine Larghetto and Humoreske, Op. 32 Silverstein/Eskin/Eskin Northeastern 219 n/a 02:23 Buy Now! Haydn, M. Symphony No. 23 in D Bournemouth Sinfonietta/Farberman MMG 10026 04716300262 Concerto No. 3 in F for Two Wind Ensembles and 02:41 Buy Now! Handel English Concert/Pinnock Archiv 415 129 028941512925 Strings 03:00 Buy Now! Beethoven Leonore Overture No. 1 Atlanta Symphony/Levi Telarc 80358 089408035821 03:10 Buy Now! Mozart Piano Quartet No. 2 in E flat, K. 493 Stern/Katims/Schneider/Istomin Sony 64516 074646451625 03:37 Buy Now! Rubbra String Quartet No.1 in F minor, Op. -

Chamber Orchestra and Concert Choir Glenn Block, Director

Illinois State University ISU ReD: Research and eData School of Music Programs Music 3-29-2013 Student Ensemble: Chamber Orchestra and Concert Choir Glenn Block, Director Karyl K. Carlson, Director Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/somp Part of the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Block,, Glenn Director and Carlson,, Karyl K. Director, "Student Ensemble: Chamber Orchestra and Concert Choir" (2013). School of Music Programs. 480. https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/somp/480 This Concert Program is brought to you for free and open access by the Music at ISU ReD: Research and eData. It has been accepted for inclusion in School of Music Programs by an authorized administrator of ISU ReD: Research and eData. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Illinois State University Chamber Orchestra Illinois State University College of Fine Arts School of Music Violin I Bassoon Ramiro Miranda, Concertmaster Katie Spitler * Maggie Watts Michael Sullivan Natalie Stawarski Gabrielle VanDril Horn Christine Hansen * Violin II Joshua Hernday Chloe Hawkins * Justin Johnson Illinois State University Chelsea Rilloraza Tyler Sutton Julia Heeren Chamber Orchestra Andrada Pteanc Trumpet Glenn Block, Music Director and Conductor Vallerie Villa Shauna Bracken * Tristan Burgmann Viola Illinois State University Matt White* Trombone Caroline Argenta Riley Leitch * Concert Choir Gillian Borth Jordan Harvey Abigail Dreher Karyl K. Carlson, Music Director and Conductor Bass Trombone Cello Grant Unnerstall* -

Stabat Mater 1831/32 Original Version with Sections by Giovanni Tadolini Giovanna D’Arco – Cantata

Gioachino ROSSINI Stabat Mater 1831/32 Original version with sections by Giovanni Tadolini Giovanna d’Arco – Cantata Majella Cullagh • Marianna Pizzolato José Luis Sola • Mirco Palazzi Camerata Bach Choir, Poznań • Württemberg Philharmonic Orchestra Antonino Fogliani Gioachino Rossini (1792-1868) * and Giovanni Tadolini (1789-1872) ** Gioachino Rossini Stabat Mater Giovanna d’Arco (°) 1831/32 original version, **orchestrated by Antonino Fogliani (b. 1976) ............................ 56:07 Solo cantata (1832) with piano accompaniment orchestrated by Marco Taralli (b. 1967) .....15:13 $ 1 I. Introduction: Stabat Mater dolorosa * ........................................................... 8:35 I. Recitativo: È notte, e tutto addormentato è il mondo ................................. 4:44 (Soloists and Chorus) (Andantino) % 2 II. Aria: Cujus animam gementem ** .................................................................. 2:40 II. Aria: O mia madre, e tu frattanto la tua figlia cercherai .............................. 3:29 (Tenor) (Andantino grazioso) ^ 3 III. Duettino: O quam tristis et afflicta ** ............................................................. 3:34 III. Recitativo: Eppur piange. Ah! repente qual luce balenò ............................ 1:14 (Soprano and Mezzo-soprano) (Allegro vivace – Allegretto) & 4 IV. Aria: Quae moerebat et dolebat ** ................................................................. 2:51 IV. Aria: Ah, la fiamma che t’esce dal guardo già m’ha tocca ......................... 5:46 (Bass) (Allegro vivace