Antonín Dvorák • Requiem

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RICHARD STRAUSS SALOME Rehearsal Room Vida Miknevičiūtė (Salome) PRESENTING VICTORIAN OPERA PRESENTS PARTNER SALOME OPERA in ONE ACT

RICHARD STRAUSS SALOME Rehearsal Room Vida Miknevičiūtė (Salome) PRESENTING VICTORIAN OPERA PRESENTS PARTNER SALOME OPERA IN ONE ACT Composer Richard Strauss Librettist Hedwig Lachmann Based on Oscar Wilde’s play Salomé Conductor Richard Mills AM Director Cameron Menzies Set Designer Christina Smith Costume Designer Anna Cordingley Lighting Designer Gavan Swift Choreographer Elizabeth Hill-Cooper CAST Salome Vida Miknevičiūtė Herod Ian Storey Jochanaan Daniel Sumegi Herodias Liane Keegan Narraboth James Egglestone Page of Herodias Dimity Shepherd Jews Paul Biencourt, Daniel Todd, Soldiers Alex Pokryshevsky, Timothy Reynolds, Carlos E. Bárcenas, Jerzy Kozlowski Raphael Wong Cappadocian Kiran Rajasingam Nazarenes Simon Meadows, Slave Kathryn Radcliffe Douglas Kelly with Orchestra Victoria Concertmaster Yi Wang 22, 25, 27 FEBRUARY 2020 Palais Theatre Original premiere 9 December 1905, Semperoper Dresden Duration 90 minutes, no interval Sung in German with English surtitles PRODUCTION PRODUCTION TEAM Production Manager Eduard Inglés Stage Manager Whitney McNamara Deputy Stage Manager Marina Milankovic Assistant Stage Manager Geetanjali Mishra MUSIC STAFF Repetiteurs Phoebe Briggs, Phillipa Safey ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Surtitles courtesy of Opera Australia ResolutionX, BAACLight Theatre, Lilydale Theatre Company © Anna Cordingley, Costume Designer P. 4 VICTORIAN OPERA 2020 SALOME ORCHESTRA CONCERTMASTER Sarah Cuming HORN Yi Wang * Philippa Gardner Section Principal Jasen Moulton VIOLIN Tania Hardy-Smith Chair supported by Mr Robert Albert Principal -

EMR 12669 Schubert Stabat Mater MF

Stabat Mater Wind Band / Concert Band / Harmonie / Blasorchester / Fanfare Arr.: John Glenesk Mortimer Franz Schubert EMR 12669 st 1 Score 2 1 Trombone + st nd 4 1 Flute 2 2 Trombone + nd 4 2 Flute 1 Bass Trombone + 1 Oboe (optional) 2 Baritone + 1 Bassoon (optional) 2 E Bass 1 E Clarinet (optional) 2 B Bass 5 1st B Clarinet 2 Tuba 4 2nd B Clarinet 1 String Bass (optional) 4 3rd B Clarinet 1 Piano Reduction (optional) 1 B Bass Clarinet (optional) 1 B Soprano Saxophone (optional) 2 1st E Alto Saxophone Special Parts Fanfare Parts 2 2nd E Alto Saxophone 1 1st B Trombone 2 1st Flugelhorn 2 B Tenor Saxophone 1 2nd B Trombone 2 2nd Flugelhorn 1 E Baritone Saxophone (optional) 1 B Bass Trombone 2 3rd Flugelhorn 1 E Trumpet / Cornet (optional) 1 B Baritone 3 1st B Trumpet / Cornet 1 E Tuba 3 2nd B Trumpet / Cornet 1 B Tuba 3 3rd B Trumpet / Cornet 2 1st F & E Horn 2 2nd F & E Horn 2 3rd F & E Horn Print & Listen Drucken & Anhören Imprimer & Ecouter≤ www.reift.ch Route du Golf 150 CH-3963 Crans-Montana (Switzerland) Tel. +41 (0) 27 483 12 00 Fax +41 (0) 27 483 42 43 E-Mail : [email protected] www.reift.ch Recorded on CD - Auf CD aufgenommen - Enregistré sur CD | Franz Schubert Photocopying Stabat Mater is illegal! Arr.: John Glenesk Mortimer 34 5 6 78 Largo q = 50 1st Flute fp p sost. fp f 2nd Flute fp p sost. fp f Oboe fp p sost. -

UBC High Notes Newsletter of the School of Music at the University of British Columbia

UBC High Notes Newsletter of the School of Music at the University of British Columbia Fall 2012 Director’s Welcome Welcome to the fourteenth edition of High Notes, celebrating the recent activities and major achievements of the faculty and students in the UBC School of Music! I think you will find the diversity and quality of accomplishments impressive and inspiring. A major highlight for me this year is the opportunity to welcome three exciting new full-time faculty members. Pianist Mark Anderson, with an outstanding international reputation gave a brilliant first recital at the School in October.Jonathan Girard, our new Director of the UBC Symphony Orchestra, and Assistant Professor of Conducting, led the UBC Symphony Orchestra in a full house of delighted audience members at the Chan Centre on November 9th. Musicologist Hedy Law, a specialist in 18th-century French opera and ballet is, has already established herself well with students and faculty in the less public sphere of our academic activities. See page 4 to meet these new faculty members who are bringing wonderful new artistic and scholarly energies to the School. It is exciting to see the School evolve through its faculty members! Our many accomplished part-time instructors are also vital to the success and profile of the School. This year we welcome to our team several UBC music alumni who have won acclaim as artists and praise as educators: cellist John Friesen, composer Jocelyn Morlock, film and television composer Hal Beckett, and composer-critic-educator David Duke. They embody the success of our programs, and the impact of the UBC School of Music on the artistic life of our province and nation. -

COMMENCEMENT CONCERT 2017 COMMENCEMENT CONCERT FRIDAY, June 9, 2017 • 8 P.M

COMMENCEMENT CONCERT 2017 COMMENCEMENT CONCERT FRIDAY, june 9, 2017 • 8 P.m. Lawrence Memorial chapel Maggie Anderson ’19 Jack Breen ’18 Allison Brooks-Conrad ’18 Elisabeth Burmeister ’17 Sarah Clewett ’17 Isabel Dammann ’17 Garrett Evans ’17 Nathan Gornick ’17 Raleigh Heath ’17 Andrew Hill ’18 Ming Hu ’17 Emmett Jackson ’18 Nicholas Kalkman ’17 Kate Kilgus ’18 Jason Koth ’17 Sara Larsen ’17 Alaina Leisten ’17 Mingfei Li ’17 Madalyn Luna ’17 Gabriella Makuc ’17 Mikaela Marget ’18 Evan Newman ’17 Nick Nootenboom ’17 Froya Olson ’17 Sam Pratt ’17 Kaira Rouer ’17 Bryn Rourke ’18 Madeline Scholl ’17 Shaye Swanson ’17 Gawain Usher ’18 Lauren Vanderlinden ’17 Erec VonSeggern ’18 1 PROGRAM From Rusalka Antonín Dvořák “Měsíčku na nebi hlubokém” (1841-1904) Etude in D minor, op. 2, no. 1 Sergei Prokofiev Froya Olson ’17, soprano (1891-1953) Susan Wenckus, piano Evan Newman ’17, piano ✦ INTERMISSION ✦ From Partenope George Frideric Handel “Furibondo spira il vento” (1685-1759) Solo Improvisation Sam Pratt Shaye Swanson ’17, mezzo-soprano (b. 1995) Nathan Birkholz, piano Sam Pratt ’17, saxophone Karate Alex Mincek Four Fragments from the Canterbury Tales Lester Trimble (b. 1975) IV. The Wyf of Biside Bathe (1923-86) Jack Breen ’18, saxophone Jason Koth ’17, saxophone Lauren Vanderlinden ’17, voice Sara Larsen ’17, flute Kate Kilgus ’18, clarinet Abegg Variations, op. 1 Robert Schumann Madeline Scholl ’17, harpsichord (1810-1856) Mingfei Li ’17, piano Toccata, op. 15 Robert Muczynski (1929-2010) Concertino Erwin Schulhoff Ming Hu ’17, piano I. Andante con moto (1894-1942) IV. Rondino: Allegro gaio Kaira Rouer ’17, flute Summer Music, op. -

Mozart Requiem September 2018

Music of the Baroque Chorus and Orchestra Jane Glover, Music Director Soprano Violin 1 Oboe Laura Amend Gina DiBello, Anne Bach, principal Alyssa Bennett Elliott Golub Honorary Erica Anderson Bethany Clearfield Concertmaster Chair Rosalind Lee Kathleen Brauer, Hannah Dixon co-assistant Basset Horn McConnell concertmaster Susan Warner, principal Susan Nelson Teresa Fream Daniel Won Bahareh Poureslami Martin Davids Emily Yiannias Michael Shelton Jeri-Lou Zike Bassoon William Buchman, Alto principal Ilana Goldstein Violin 2 Lewis Kirk Julia Hardin Sharon Polifrone, Amanda Koopman principal Maggie Mascal Ann Palen Trumpet Quinn Middleman Rika Seko Barbara Butler, co- Anna VanDeKerchove Paul Vanderwerf principal Helen Kim Charles Geyer, co- principal Tenor Channing Philbrick Sam Grosby Viola Patrick Muehleise Elizabeth Hagen, Josh R. Pritchett principal Trombone Ryan Townsend Strand Claudia Lasareff- Reed Capshaw, principal Zachary Vanderburg Mironoff David Binder Christopher Windle Benton Wedge Jared Rodin Amy Hess Bass Timpani Cornelius Bouknight Cello Douglas Waddell Cody Michael Bradley Barbara Haffner, Corey Grigg principal Jan Jarvis Judy Stone Organ Nicholas Lin Mark Brandfonbrener Stephen Alltop Dylan Martin Bass Collins Trier, principal Michael Hovnanian The Mozart Requiem Jane Glover, conductor William Jon Gray, chorus director Saturday, September 15, 2018, 7:30 PM Harris Theater for Music and Dance, Chicago Sunday, September 16, 2018, 3:00 PM North Shore Center for the Performing Arts, Skokie Coronation Anthem No. 1, “Zadok the Priest” -

The Magic Flute Programme

Programme Notes September 4th, Market Place Theatre, Armagh September 6th, Strule Arts Centre, Omagh September 10th & 11th, Lyric Theatre, Belfast September 13th, Millennium Forum, Derry-Londonderry 1 Welcome to this evening’s performance Brendan Collins, Richard Shaffrey, Sinéad of The Magic Flute in association with O’Kelly, Sarah Richmond, Laura Murphy Nevill Holt Opera - our first ever Mozart and Lynsey Curtin - as well as an all-Irish production, and one of the most popular chorus. The showcasing and development operas ever written. of local talent is of paramount importance Open to the world since 1830 to us, and we are enormously grateful for The Magic Flute is the first production of the support of the Arts Council of Northern Austins Department Store, our 2014-15 season to be performed Ireland which allows us to continue this The Diamond, in Northern Ireland. As with previous important work. The well-publicised Derry / Londonderry, seasons we have tried to put together financial pressures on arts organisations in Northern Ireland an interesting mix of operas ranging Northern Ireland show no sign of abating BT48 6HR from the 18th century to the 21st, and however, and the importance of individual combining the very well known with the philanthropic support and corporate Tel: +44 (0)28 7126 1817 less frequently performed. Later this year sponsorship has never been greater. I our co-production (with Opera Theatre would encourage everyone who enjoys www.austinsstore.com Company) of Donizetti’s L’Elisir d’Amore seeing regular opera in Northern Ireland will tour the Republic of Ireland, following staged with flair and using the best local its successful tour of Northern Ireland operatic talent to consider supporting us last year. -

DVORÁK of Eight Pieces for Piano Duet

GRZEGORZ NOWAK CONDUCTS DVO RÁK Symphonies no 6 - 9 Carnival Overture 3 CDs ˇ composer complied in 1878 with a set Symphony No.6 in D major, Op.60 the Vienna cancellation must have galled ANTONÍN DVORÁK of eight pieces for piano duet. These did the composer, was a resounding success. I. Allegro non tanto The work was published in Berlin in 1882 as (1841-1904) much to enhance his reputation abroad, II. Adagio and in 1884 he was invited to conduct ‘Symphony No.1’, ignoring the fact it actually III. Scherzo: Furiant-Presto had five symphonic predecessors, and leading his Stabat Mater in London, where his Antonín Dvorˇák was born in what was IV. Finale: Allegro con spirito to a situation where the celebrated work we music became immensely popular. In then known as Bohemia, in the small In the mid-1870s Dvorˇák, then in his now know as the Ninth appeared in print village of Mühlhausen, near Prague. 1891 he was made an honorary Doctor mid-thirties, was still struggling to gain as the Fifth. He was apprenticed as a butcher in of Music by Cambridge University and recognition and renown outside his native Dvorˇák’s earlier symphonies were strongly the following year made the first of his country. In 1874 he was awarded the first his father’s shop, encountering strong influenced by those of Beethoven. Indeed, visits to America, a country that would of several Austrian State Stipendium grants, paternal opposition to his intended his First Symphony, which was composed through which he made the acquaintance career as a musician. -

82890-5 First Book Dvorak Jb.Indd 3 8/22/18 12:09 PM Pastorale from Czech Suite Op

Contents Author’s Note i v Pastorale 1 Kyrie 2 Symphony No. 9, Mvt. IV (Theme) 3 Silhouettes 4 String Quintet No. 12 5 Prague Waltzes 6 Romance 7 Symphony No. 8, Mvt. IV (Theme) 8 Waltz 9 Romantic Pieces 1 0 Symphony No. 9, Mvt. I (Theme) 1 1 Song to the Moon 1 2 In a Ring! 1 4 Bacchanale 1 6 Songs My Mother Taught Me 1 7 Mazurka 1 8 Cypresses 2 0 Cello Concerto 2 1 Grandpa Dances with Grandma 2 2 Mazurka 2 4 Stabat Mater 2 6 The Question 2 7 Chorus of the Water Nymphs 2 8 Capriccio 2 9 The Water Goblin 3 0 Ballade 3 1 Serenade for Strings 3 2 Dumka 3 3 The Noon Witch 3 4 Symphony No. 9, Mvt. II (Largo) 3 6 Serenade for Wind Instruments 3 7 Slavonic Dances 3 8 Violin Concerto Mvt. I 3 9 Violin Concerto Mvt. II 4 0 Six Piano Pieces 4 2 Humoresque 4 4 82890-5 First Book Dvorak jb.indd 3 8/22/18 12:09 PM Pastorale from Czech Suite Op. 39 A pastorale is a musical composition intended to evoke images of nature and the countryside. This rustic melody is supported by a static left hand playing an open fifth (C–G). The effect is known as a drone and is reminiscent of old folk instruments. 1 82890-5 First Book Dvorak jb.indd 1 8/22/18 12:09 PM Kyrie from Mass Op. 86 The Kyrie is the traditional first movement of the Mass. -

A Conductor's Analysis of Amaral Vieira's Stabat Mater, Op.240: an Approach Between Music and Rhetoric Vladimir A

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2005 A conductor's analysis of Amaral Vieira's Stabat Mater, op.240: an approach between music and rhetoric Vladimir A. Pereira Silva Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Pereira Silva, Vladimir A., "A conductor's analysis of Amaral Vieira's Stabat Mater, op.240: an approach between music and rhetoric" (2005). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3618. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3618 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. A CONDUCTOR’S ANALYSIS OF AMARAL VIEIRA’S STABAT MATER, OP. 240: AN APPROACH BETWEEN MUSIC AND RHETORIC A Monograph Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The School of Music by Vladimir A. Pereira Silva B.M.E., Universidade Federal da Paraíba, 1992 M. Mus., Universidade Federal da Bahia, 1999 May, 2005 © Copyright 2005 Vladimir A. Pereira Silva All rights reserved ii In principio erat Verbum et Verbum erat apud Deum et Deus erat Verbum. Evangelium Secundum Iohannem, Caput 1:1 iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This dissertation would have not been possible without the support of many people and institutions throughout the last several years, and I would like to thank them all for a great graduate school experience. -

The Ultimate On-Demand Music Library

2020 CATALOGUE Classical music Opera The ultimate Dance Jazz on-demand music library The ultimate on-demand music video library for classical music, jazz and dance As of 2020, Mezzo and medici.tv are part of Les Echos - Le Parisien media group and join their forces to bring the best of classical music, jazz and dance to a growing audience. Thanks to their complementary catalogues, Mezzo and medici.tv offer today an on-demand catalogue of 1000 titles, about 1500 hours of programmes, constantly renewed thanks to an ambitious content acquisition strategy, with more than 300 performances filmed each year, including live events. A catalogue with no equal, featuring carefully curated programmes, and a wide selection of musical styles and artists: • The hits everyone wants to watch but also hidden gems... • New prodigies, the stars of today, the legends of the past... • Recitals, opera, symphonic or sacred music... • Baroque to today’s classics, jazz, world music, classical or contemporary dance... • The greatest concert halls, opera houses, festivals in the world... Mezzo and medici.tv have them all, for you to discover and explore! A unique offering, a must for the most demanding music lovers, and a perfect introduction for the newcomers. Mezzo and medici.tv can deliver a large selection of programmes to set up the perfect video library for classical music, jazz and dance, with accurate metadata and appealing images - then refresh each month with new titles. 300 filmed performances each year 1000 titles available about 1500 hours already available in 190 countries 2 Table of contents Highlights P. -

Michaela Kaune Soprano

Konstantin Unger Artists.Management Scheffelstrasse 11 | D - 65187 Wiesbaden +49 611 51 0099 76 / +49 176 846 24 222 [email protected] www.ungerartists.com Michaela Kaune Soprano The internationally highly demanded soprano Michaela Kaune has invitations to major opera companies all over the world. Recently she sang Sieglinde in Beijing in WALKÜRE, a coproduction of the Salzburg Easter Festival and the Beijing Music Festival. With the same role she has been invited to the Grand Théâtre de Genève. At the Staatsoper Berlin she had to cancel due to the corona virus the role of Leonore in FIDELIO (2020). In June 2018 she made her Glyndebourne Festival debut as Marschallin in ROSENKAVALIER. Later this year, in September, Michaela Kaune sang the same role at the Ópera de Colombia in Bogotá. The Marschallin, one of her signature roles she sang in houses like the Opéra de Paris, the Bavarian State Opera, the Deutsche Oper Berlin, the China National Centre for the Performing Arts, Beijing a.o. She made her Elbphilharmonie-debut with the final scene of CAPRICCIO under Marek Janowski. In the title role of JENUFA she was invited to the New National Theatre, Tokyo and the Deutsche Oper Berlin. The DVD of this production with Michaela Kaune had been nominated for the Grammy Award 2016. Further engagements include Elettra in IDOMENEO (role debut) at the Teatro la Fenice, Ellen Orford in PETER GRIMES at the Deutsche Oper Berlin, Sieglinde in WALKÜRE at the Budapest Wagner Festival and in concert performances with the Bamberg Symphonic Orchestra and the title role of ARIADNE AUF NAXOS at the Zurich Opera. -

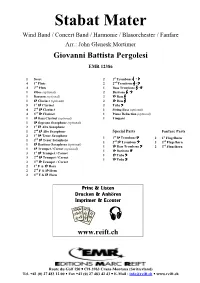

EMR 12386 Stabat Mater WB

Stabat Mater Wind Band / Concert Band / Harmonie / Blasorchester / Fanfare Arr.: John Glenesk Mortimer Giovanni Battista Pergolesi EMR 12386 st 1 Score 2 1 Trombone + st nd 4 1 Flute 2 2 Trombone + nd 4 2 Flute 1 Bass Trombone + 1 Oboe (optional) 2 Baritone + 1 Bassoon (optional) 2 E Bass 1 E Clarinet (optional) 2 B Bass 5 1st B Clarinet 2 Tuba 4 2nd B Clarinet 1 String Bass (optional) 4 3rd B Clarinet 1 Piano Reduction (optional) 1 B Bass Clarinet (optional) 1 Timpani 1 B Soprano Saxophone (optional) st 2 1 E Alto Saxophone 1 2nd E Alto Saxophone Special Parts Fanfare Parts st 2 1 B Tenor Saxophone 1 1st B Trombone 2 1st Flugelhorn 1 2nd B Tenor Saxophone 1 2nd B Trombone 2 2nd Flugelhorn 1 E Baritone Saxophone (optional) 1 B Bass Trombone 2 3rd Flugelhorn 1 E Trumpet / Cornet (optional) 1 B Baritone 3 1st B Trumpet / Cornet 1 E Tuba 3 2nd B Trumpet / Cornet 1 B Tuba 3 3rd B Trumpet / Cornet 2 1st F & E Horn 2 2nd F & E Horn 2 3rd F & E Horn Print & Listen Drucken & Anhören Imprimer & Ecouter≤ www.reift.ch Route du Golf 150 CH-3963 Crans-Montana (Switzerland) Tel. +41 (0) 27 483 12 00 Fax +41 (0) 27 483 42 43 E-Mail : [email protected] www.reift.ch DISCOGRAPHY Baroque Splendour Volume 2 Track Titel / Title Time N° EMR N° EMR N° (Komponist / Composer) Blasorchester Brass Band Concert Band 1 Rondeau (Les Indes Galantes) (Rameau) 1’51 EMR 12220 EMR 32124 2 Le Basque (Marais) 2’24 EMR 12611 EMR 32125 3 Tambourin (Dardanus) (Rameau) 2’29 EMR 12213 EMR 32126 4 Marche Royale (Lully) 2’18 EMR 12226 EMR 9855 5 Symphonies pour