Lieder Recital

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Ultimate On-Demand Music Library

2020 CATALOGUE Classical music Opera The ultimate Dance Jazz on-demand music library The ultimate on-demand music video library for classical music, jazz and dance As of 2020, Mezzo and medici.tv are part of Les Echos - Le Parisien media group and join their forces to bring the best of classical music, jazz and dance to a growing audience. Thanks to their complementary catalogues, Mezzo and medici.tv offer today an on-demand catalogue of 1000 titles, about 1500 hours of programmes, constantly renewed thanks to an ambitious content acquisition strategy, with more than 300 performances filmed each year, including live events. A catalogue with no equal, featuring carefully curated programmes, and a wide selection of musical styles and artists: • The hits everyone wants to watch but also hidden gems... • New prodigies, the stars of today, the legends of the past... • Recitals, opera, symphonic or sacred music... • Baroque to today’s classics, jazz, world music, classical or contemporary dance... • The greatest concert halls, opera houses, festivals in the world... Mezzo and medici.tv have them all, for you to discover and explore! A unique offering, a must for the most demanding music lovers, and a perfect introduction for the newcomers. Mezzo and medici.tv can deliver a large selection of programmes to set up the perfect video library for classical music, jazz and dance, with accurate metadata and appealing images - then refresh each month with new titles. 300 filmed performances each year 1000 titles available about 1500 hours already available in 190 countries 2 Table of contents Highlights P. -

Mass in C Minor Performances of Two Academy of St Martin Fine Choral Works from in the Fields Two Masters of the Baroque Era

CORO CORO Vivaldi: Gloria in D Fauré: Requiem Bach: Magnificat in D Mozart: Vespers Harry Christophers Elin Manahan Thomas MOZART The Sixteen Roderick Williams Harry Christophers Resounding The Sixteen Mass in C minor performances of two Academy of St Martin fine choral works from in the Fields two masters of the Baroque era. “…the sense of an ecstatic movement towards cor16057 cor16042 cor16057 Paradise is tangible.” the times Handel: Messiah Barber: Agnus Dei 3 CDs (Special Edition) An American Collection Carolyn Sampson Barber, Bernstein, Catherine Wyn-Rogers Copland, Fine, Reich, Mark Padmore del Tredici Christopher Purves “The Sixteen are, as “…this inspiriting new usual, in excellent form performance becomes here. Recording and a first choice.” remastering are top- notch.” Gillian Keith the daily telegraph notch.” cor16062 cor16031 american record guide Tove Dahlberg Harry Christophers Thomas Cooley To find out more about CORO and to buy CDs visit Handel and Haydn Society Nathan Berg www.thesixteen.com cor16084 ne of the many delights of being of your seat” suspense that one feels in the exquisite ‘Et incarnatus est’ and it OArtistic Director of America’s is well worth that risk. One can never achieve this degree of concentration and oldest continuously performing arts total immersion in the music whilst in the recording studio; whatever mood is organization, the Handel and Haydn set, subconsciously we always know we can have another go at it. Society, is that I am given the opportunity to present most of our concert season at I feel very privileged to take this august Society towards its Bicentennial; yes, the Handel and Haydn Society was founded in 1815. -

Antonín Dvorák • Requiem

Antonín Dvorˇák • Requiem Ilse Eerens – Bernarda Fink – Maximilian Schmitt – Nathan Berg Collegium Vocale Gent – Royal Flemish Philharmonic Philippe Herreweghe Tracklist – p. 5 English – p. 8 Français – p. 13 Deutsch – p. 19 Nederlands – p. 25 Sung Texts – p. 30 Antonín Dvorˇák (1841-1904) Requiem, Op. 89 Ilse Eerens soprano Bernarda Fink alto Maximilian Schmitt tenor Nathan Berg bass Collegium Vocale Gent Royal Flemish Philharmonic Philippe Herreweghe Recording: April 28-30, 2014, deSingel, Antwerp — Sound Engineer: Markus Heiland (Tritonus) — Editing: Markus Heiland & Andreas Neubronner (Tritonus) — Recording Producer, Mastering: Andreas Neubronner (Tritonus) — Liner Notes: Tom Janssens — Cover picture: photo Michel Dubois (Courtesy Dubois Friedland) — Photographs Philippe Herreweghe: Michiel Hendryckx — Design: Casier/Fieuws — Executive Producer: Aliénor Mahy MENU CD 1 INTROITUS [1] Requiem æternam – Kyrie eleison (Soli and Chorus)........................................................10’44 GRADUALE [2] Requiem æternam (Soprano and Chorus)......................................................................04’38 SEQUENTIA [3] Dies iræ (Chorus).......................................................................................................02’28 [4] Tuba mirum (Soli and Chorus) ....................................................................................08’35 [5] Quid sum miser (Soli and Chorus) ...............................................................................06’02 [6] Recordare, Jesu pie (Soli) .............................................................................................07’03 -

Biographies of Composers & Presenters

BIOGRAPHIES OF COMPOSERS & PRESENTERS Admiral, Roger Canadian pianist Roger Admiral performs solo and chamber music repertoire spanning the 18th through the 21st century. Known for his dedication to contemporary music, Roger has commissioned and premiered many new compositions. He works regularly with UltraViolet (New Music Edmonton) and Aventa Ensemble (Victoria), and performs as part of Kovalis Duo with Montreal percussionist Philip Hornsey. Roger also coaches contemporary chamber music at the University of Alberta. Recent performances include Gyorgy Ligeti’s Piano Concerto with the Victoria Symphony Orchestra, the complete piano works of Iannis Xenakis for Vancouver New Music, a recital with baritone Nathan Berg at Lincoln Center’s Great Performers Series (New York City), and recitals for Curto-Circuito de Música Contemporânea Brazil with saxophonist Allison Balcetis, as well as solo recitals in Bratislava, Budapest, and Wroclaw. Roger can be heard on CD recordings of piano music by Howard Bashaw (Centrediscs) and Mark Hannesson (Wandelweiser Editions). Alexander, Justin Justin Alexander is an Assistant Professor of Music at Virginia Commonwealth University where he teaches Applied Percussion Lessons, Percussion Methods and Techniques, Introduction to World Musical Styles, Music and Dance Forms, and directs the VCU Percussion Ensemble. Justin is a founding member of Novus Percutere, with percussionist Dr. Luis Rivera, and The AarK Duo, with flutist Dr. Tabatha Easley. Recent highlights include collaborative performances in Sweden, Australia, the Percussive Arts Society International Convention, and at the 6th International Conference on Music and Minimalism in Knoxville, Tennessee. As a soloist, Justin focuses on the creation of new works for percussion through commissions and compositions, specifically focusing on post-minimalist/process/iterative keyboard music, non-western percussion, and drum set. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Summer

BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA SEIJI OZAWA, MUSIC DIRECTOR Tanglewrod 19 9 7 HOLSTEN GALLERIE CHIHULY GLASS SCULPTURE • PAINTINGS • ART JEWELRY Elm Street, Stockbridge, Mass. 01262 (413) 298-3044 W Seiji Ozawa, Music Director Bernard Haitink, Principal Guest Conductor One Hundred and Sixteenth Season, 1996-97 Trustees of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Inc. R W Mis I eith, Ji.. Chairman Nicholas T. Zervas, President Petei V Brooke, Vice-Chavrman William J. Poorvu, Vice-Chairman and Treasurer Mis. Edith L. Dabney, Vice-Chairman Ray Stata, Vice-Chairman H.u\<\ ( In i Km in/in. in, Vice-Chairman I Lilian I Vnderson William M. Crozier, Jr. Edna S. Kalman Robert P. O' Block Dr. \in.ii ( .. Bose Nader F. Darehshori George Krupp ex-officio Peter C. Read [.lilies | ( | ( .1) \ Deborah B. Davis Mrs. August R. Meyer Margaret Williams- |i>lui 1 ( ogan, Jr. Nina L. Doggett Richard P. Morse DeCelles, Julian ( oliin AvramJ. Goldberg Mrs. Robert B. Newman ex-officio \\ illiaiu F. ( lonnell Thelma E. Goldberg i\ officio Julian T. Houston Life Trustees Vei nun R. Alden Archie C. Epps Mrs. George I. Mrs. George Lee David B. Arnold, Jr. Mrs. John H. Kaplan Sargent J.P.Bargei Fitzpatrick George H. Kidder Sidney Stoneman Leo L. Beranek Dean W. Freed Thomas D. Perry, Jr. John Hoyt Stookey L. \l)i am I ( oilier Mrs. John L. Irving W. Rabb John Thorndike Nelson | Dai ling, Ji. Grandin Other Officers of the Corporation Daniel R. Gustin, Clerk I homas D. Ma) and John Ex Rodgers, Assistant Treasurers Board of Overseers of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Inc Robei i P. -

Coronation Mass

CORO CORO Mozart: Mass in C minor Harry Christophers & Handel and Haydn Society MOZART Gillian Keith, Tove Dahlberg, Thomas Cooley, Nathan Berg Coronation Mass “…a commanding and compelling reading of an important if often overlooked monument in Mozart’s musical development.” cor16084 gramophone recommended Mozart: Requiem Harry Christophers & Handel and Haydn Society Elizabeth Watts, Phyllis Pancella, Andrew Kennedy, Eric Owens “A requiem full of life…Mozart’s final masterpiece has never sounded so exciting.” classic fm magazine Teresa Wakim cor16093 Paula Murrihy Harry Christophers Thomas Cooley To find out more about CORO and to buy CDs visit Handel and Haydn Society Sumner Thompson www.thesixteen.com cor16104 ne of the many delights of being I feel very privileged to take this august Society towards its Bicentennial; yes, the OArtistic Director of America's oldest Handel and Haydn Society was founded in 1815. Handel was the old, Haydn the new continuously performing arts organisation, the (he had just died in 1809), and what we can do is continue to perform the music of the Handel and Haydn Society, is that I am given past but strip away the cobwebs and reveal it anew. This recording of music by Haydn the opportunity to present most of our concert and Mozart was made possible by individuals who are inspired by the work of the season at Boston's glorious Symphony Hall. Built Handel and Haydn Society. Our sincere thanks go to all of them. in 1900, it is principally the home of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, but it has been our primary Borggreve Marco Photograph: performance home since 1900 as well, and it is considered by many, with some justification I would add, to be one of the finest concert halls in the world. -

Cds März 2020

NEUERWERBUNGEN MUSIK -CDS ZUR AUSLEIHE MÄRZ 2020 NEUERWERBUNGEN MUSIK -CD S ZUR AUSLEIHE MÄRZ 2020 Inhalt Vokalmusik: Gesang für Einzelstimmen ........................................................................ 3 Vokalmusik: Chorgesang ..................................................................................................... 3 Bühnenwerke. Dramatische Musik .................................................................................. 3 Instrumentalmusik: Einzelinstrumente .......................................................................... 4 Instrumentalmusik: Kammermusik ................................................................................. 5 Instrumentalmusik: Werke für Soloinstrumente und Orchester .......................... 5 Instrumentalmusik: Orchesterwerke .............................................................................. 5 Instrumentalmusik: Porträts .............................................................................................. 6 Vermischte Editionen und Sammelprogramme ......................................................... 6 Elektronische Musik. Musique concrète. Experimentelle Musik ........................... 6 Außereuropäische Volks- und Kunstmusik. Europäische Volksmusik ................ 6 Jazz .............................................................................................................................................. 7 Rockmusik. Popmusik .......................................................................................................... -

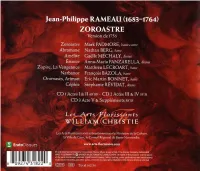

ZOROASTRE Version De 1756

Jean-Philippe RAMEAU (1683-1764) ZOROASTRE Version de 1756 Zoroastre Mark PADMORE, haute<outre Abramane Nathan BERG, basse Amélite Gaëlle MÉCHALY, dessus Érinice Anna-Maria PANZARELLA, dessus Zopire, La Vengeance Matthieu LÉCROART, basse Narbanor François BAZOLA, basse Oromasès, Ariman Éric Martin BONNET, basse Céphie Stéphanie REVIDAT, dessus CD 1 Actes I & 11 68'08 CD 2 Actes 111 & IV 55'51 CD 3 Acte V & Suppléments 38'35 Rameau zoroastre RAMEAU Z O ROAS TRE JEAN-PHILIPPE RAMEAU (1683-1764) Zoroastre^ Livret de Louis de Cahusac Version de 1756 ZOROASTRE, instituteur des Mages Mark Padmore, haute-contre founder of the Magi der Lehrmeister der Magier ABRAMANE, Grand Prêtre d'Ariman Nathan Berg, basse High Priest of Ariman • Oberpriester des Ariman AMÉLITE, héritière présomptive du trône de la Bactriane Gaëlle Méchaly, dessus presumptive heiress to the throne of Bactria die mutmaßliche Thronfolgerin des Königreichs Baktrien ÉRINICE, princesse du sang des rois de la Bactriane Anna Maria Panzarella, dessus princess of the blood ofthe kings ofBactria eine Prinzessin aus dem Geblüt der Könige von Baktrien ZOPIRE, prêtre d'Ariman Matthieu Lécroart, basse priest of Ariman - Priester des Ariman NARBANOR, prêtre d'Ariman François Bazola, basse priest of Ariman Priester des Ariman OROMASÈS, roi des Génies Éric Martin Bonnet, basse king of the Genii - der König der guten Geister CÉPHIE, jeune Bactrienne de la Cour d'Amélite Stéphanie Révidat, dessus Bactrian girl ofAme'lite's court eine junge Baktrerin am Hofe Amelites LA VENGEANCE Matthieu Lécroart, -

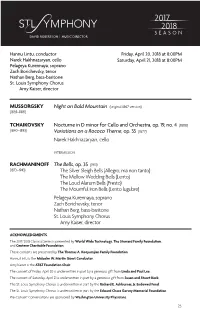

Night on Bald Mountain (Original 1867 Version) (1839–1881)

2017 2018 SEASON Hannu Lintu, conductor Friday, April 20, 2018 at 8:00PM Narek Hakhnazaryan, cello Saturday, April 21, 2018 at 8:00PM Pelageya Kurennaya, soprano Zach Borichevsky, tenor Nathan Berg, bass-baritone St. Louis Symphony Chorus Amy Kaiser, director MUSSORGSKY Night on Bald Mountain (original 1867 version) (1839–1881) TCHAIKOVSKY Nocturne in D minor for Cello and Orchestra, op. 19, no. 4 (1888) (1840–1893) Variations on a Rococo Theme, op. 33 (1877) Narek Hakhnazaryan, cello INTERMISSION RACHMANINOFF The Bells, op. 35 (1913) (1873–1943) The Silver Sleigh Bells (Allegro, ma non tanto) The Mellow Wedding Bells (Lento) The Loud Alarum Bells (Presto) The Mournful Iron Bells (Lento lugubre) Pelageya Kurennaya, soprano Zach Borichevsky, tenor Nathan Berg, bass-baritone St. Louis Symphony Chorus Amy Kaiser, director ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The 2017/2018 Classical Series is presented by World Wide Technology, The Steward Family Foundation, and Centene Charitable Foundation. These concerts are presented by The Thomas A. Kooyumjian Family Foundation. Hannu Lintu is the Malcolm W. Martin Guest Conductor. Amy Kaiser is the AT&T Foundation Chair. The concert of Friday, April 20 is underwritten in part by a generous gift from Linda and Paul Lee. The concert of Saturday, April 21 is underwritten in part by a generous gift from Susan and Stuart Keck. The St. Louis Symphony Chorus is underwritten in part by the Richard E. Ashburner, Jr. Endowed Fund. The St. Louis Symphony Chorus is underwritten in part by the Edward Chase Garvey Memorial Foundation. Pre-Concert Conversations are sponsored by Washington University Physicians. 23 RUSSIAN ORIGINALS BY RENÉ SPENCER SALLER TIMELINKS “My music is the product of my temperament, and so it is Russian music,” Serge Rachmaninoff declared. -

Alcina / Tamerlano LA MONNAIE/DE MUNT

©Photo: LaMonnaie Alcina / Tamerlano LA MONNAIE/DE MUNT > OPERA 2015 HDTV Alcina Opera in three acts by George Frideric Handel filmeD aT La Monnaie/De Munt, Brussels (1735) | Anonymous libretto after Orlando furioso, in February 2015 adapted from the libretto L’isola di Alcina | tv DirecTor Myriam Hoyer (Alcina) Tamerlano Opera in three acts by George Frideric and Stephan Aubé (Tamerlano) Handel (1724) | Libretto by Nicola Francesco Haym | running Time 195’ and 190’ Alcina / Tamerlano artistic information ALCINA TAMERLANO synopsis Like Handel’s Orlando (1732) and Ariodante synopsis Tamerlano, inspired by the historical confrontation of (1734), Alcina derives from the narrative material in 1402 between Sultan Bayezid I and Timur Lenk, tells the story Ariosto’s Orlando furioso. The story of the sorceress of the clash of two strong personalities : Tamerlano as the Alcina, an initially hedonistic, manipulative woman who victor, Bajazet as the loser who has no intention of grovelling later finds herself a victim of love, fits into the genre of humbly in the dust. Following the success of Giulio Cesare in the ‘magical opera’ with numerous magical elements, but Egitto, Handel completed his highly expressive Tamerlano after Handel achieved considerable emotional authenticity in numerous revisions. The underlying tone of the work is serious ; his characterisations. This makes Alcina one of the most the composer tried to give depth to the characterisation of the deeply felt and multifaceted operas. ‘You may despise historical figures. The scene preceding the death of Bajazet – a what you like ; but you cannot contradict Handel,’ said the major part which, exceptionally, was written for a tenor – is the Irish playwright George Bernard Shaw. -

Alban BERG Wozzeck

Alban BERG Wozzeck Trekel • Schwanewilms Molomot • Berg Gietz • McPherson Ciesinski • Griffin Schultz • Ryan Houston Symphony Hans Graf Alban CD 1 36:22 BERG Act I (1885-1935) 1 Scene 1: Zimmer des Hauptmanns (The Captain’s Room) ‘Langsam, Wozzeck, langsam!’ (Captain, Wozzeck) 8:02 2 Scene 2: Freies Feld, die Stadt in der Ferne (An open field outside the town) Wozzeck (1917-1922) ‘Du, der Platz ist verflucht!’ (Wozzeck, Andres) 8:00 Opera in Three Acts 3 Scene 3: Mariens Stube (Marie’s Room) ‘Tschin Bum, Tschin, Bum! Hörst Bub?’ (Marie, Margret, Marie’s Child (silent), Wozzeck) 8:42 4 Scene 4: Studierstube des Doktors (The Doctor’s study) Text by Georg Büchner (1813-1837) ‘Was erleb’ ich Wozzeck?’ (Doctor, Wozzeck) 7:35 5 Scene 5: Strasse vor Mariens Wohnung (Street before Marie’s Door) Wozzeck . Roman Trekel, Baritone ‘Geh einmal vor Dich hin!’ (Marie, Drum-major) 4:04 Marie . Anne Schwanewilms, Soprano CD 2 61:30 Captain (Hauptmann) . Marc Molomot, Tenor Doctor (Doktor) . Nathan Berg, Bass-baritone Act II Drum-major (Tambourmajor) . Gordon Gietz, Tenor 1 Scene 1: Mariens Stube (Marie’s Room) ‘Was die Steine glänzen?’ (Marie, Marie’s Child (silent), Wozzeck) 5:59 Andres . Robert McPherson, Tenor 2 Scene 2: Strasse in der Stadt (Street in town) Margret . Katherine Ciesinski, Mezzo-soprano ‘Wohin so eilig, gehertester, Herr Sargnagel?’ (Captain, Doctor, Wozzeck) 10:10 First Apprentice (Erster Handwerksbursche) . Calvin Griffin, Bass-baritone 3 Scene 3: Strasse vor Mariens Wohnung (Street before Marie’s Door) ‘Guten tag, Franz’ (Marie, Wozzeck) 4:54 Second Apprentice (Zweiter Handwerksbursche) . Samuel Schultz, Baritone 4 Scene 4: Wirtshausgarten (Tavern Garden) Madman (Der Narr) . -

Boston Baroque Announces 2019-2020 Season

Media Contact: Emily Kirk Weddle, Boston Baroque [email protected] 617-987-8600 For Immediate Release: Boston Baroque Announces 2019-2020 Season Season bookended by two performances that highlight opera: October concert program of arias and symphonies featuring Amanda Forsythe and April semi-staged performance of Handel’s Ariodante with Paula Murrihy in the title role. BOSTON, MA—GRAMMY®-nominated Boston Baroque is delighted to announce its 2019-2020 season. The season—led by founding Music Director and Conductor Martin Pearlman—features some of the most beloved music of the repertoire performed by a roster of world-class soloists and the ensemble’s celebrated orchestra and chorus. In addition to its annual Messiah and New Year’s Eve performances, the season includes Vivaldi’s The Four Seasons featuring concertmaster Christina Day Martinson paired with his vibrant choral masterpiece, the Gloria in D; Mozart’s “Linz” Symphony, Haydn’s Symphony No. 102, and concert arias sung by beloved soprano Amanda Forsythe; and closing the season Boston Baroque’s much-anticipated annual semi- staged opera, Handel’s Ariodante, with Paula Murrihy in the title role. Season subscriptions start at $81 and may be purchased at bostonbaroque.org and 617-987-8600. Subscriptions are available beginning March 11th and single tickets will go on sale this summer. The season opens on Friday, October 25th and Sunday, October 27th with a program that brings together music of the operatic and symphonic stages. Martin Pearlman will lead the Boston Baroque orchestra in performances of Mozart’s “Linz” Symphony No. 36 in C and Haydn’s Symphony No.