Stabat Mater Op

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EMR 12669 Schubert Stabat Mater MF

Stabat Mater Wind Band / Concert Band / Harmonie / Blasorchester / Fanfare Arr.: John Glenesk Mortimer Franz Schubert EMR 12669 st 1 Score 2 1 Trombone + st nd 4 1 Flute 2 2 Trombone + nd 4 2 Flute 1 Bass Trombone + 1 Oboe (optional) 2 Baritone + 1 Bassoon (optional) 2 E Bass 1 E Clarinet (optional) 2 B Bass 5 1st B Clarinet 2 Tuba 4 2nd B Clarinet 1 String Bass (optional) 4 3rd B Clarinet 1 Piano Reduction (optional) 1 B Bass Clarinet (optional) 1 B Soprano Saxophone (optional) 2 1st E Alto Saxophone Special Parts Fanfare Parts 2 2nd E Alto Saxophone 1 1st B Trombone 2 1st Flugelhorn 2 B Tenor Saxophone 1 2nd B Trombone 2 2nd Flugelhorn 1 E Baritone Saxophone (optional) 1 B Bass Trombone 2 3rd Flugelhorn 1 E Trumpet / Cornet (optional) 1 B Baritone 3 1st B Trumpet / Cornet 1 E Tuba 3 2nd B Trumpet / Cornet 1 B Tuba 3 3rd B Trumpet / Cornet 2 1st F & E Horn 2 2nd F & E Horn 2 3rd F & E Horn Print & Listen Drucken & Anhören Imprimer & Ecouter≤ www.reift.ch Route du Golf 150 CH-3963 Crans-Montana (Switzerland) Tel. +41 (0) 27 483 12 00 Fax +41 (0) 27 483 42 43 E-Mail : [email protected] www.reift.ch Recorded on CD - Auf CD aufgenommen - Enregistré sur CD | Franz Schubert Photocopying Stabat Mater is illegal! Arr.: John Glenesk Mortimer 34 5 6 78 Largo q = 50 1st Flute fp p sost. fp f 2nd Flute fp p sost. fp f Oboe fp p sost. -

82890-5 First Book Dvorak Jb.Indd 3 8/22/18 12:09 PM Pastorale from Czech Suite Op

Contents Author’s Note i v Pastorale 1 Kyrie 2 Symphony No. 9, Mvt. IV (Theme) 3 Silhouettes 4 String Quintet No. 12 5 Prague Waltzes 6 Romance 7 Symphony No. 8, Mvt. IV (Theme) 8 Waltz 9 Romantic Pieces 1 0 Symphony No. 9, Mvt. I (Theme) 1 1 Song to the Moon 1 2 In a Ring! 1 4 Bacchanale 1 6 Songs My Mother Taught Me 1 7 Mazurka 1 8 Cypresses 2 0 Cello Concerto 2 1 Grandpa Dances with Grandma 2 2 Mazurka 2 4 Stabat Mater 2 6 The Question 2 7 Chorus of the Water Nymphs 2 8 Capriccio 2 9 The Water Goblin 3 0 Ballade 3 1 Serenade for Strings 3 2 Dumka 3 3 The Noon Witch 3 4 Symphony No. 9, Mvt. II (Largo) 3 6 Serenade for Wind Instruments 3 7 Slavonic Dances 3 8 Violin Concerto Mvt. I 3 9 Violin Concerto Mvt. II 4 0 Six Piano Pieces 4 2 Humoresque 4 4 82890-5 First Book Dvorak jb.indd 3 8/22/18 12:09 PM Pastorale from Czech Suite Op. 39 A pastorale is a musical composition intended to evoke images of nature and the countryside. This rustic melody is supported by a static left hand playing an open fifth (C–G). The effect is known as a drone and is reminiscent of old folk instruments. 1 82890-5 First Book Dvorak jb.indd 1 8/22/18 12:09 PM Kyrie from Mass Op. 86 The Kyrie is the traditional first movement of the Mass. -

A Conductor's Analysis of Amaral Vieira's Stabat Mater, Op.240: an Approach Between Music and Rhetoric Vladimir A

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2005 A conductor's analysis of Amaral Vieira's Stabat Mater, op.240: an approach between music and rhetoric Vladimir A. Pereira Silva Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Pereira Silva, Vladimir A., "A conductor's analysis of Amaral Vieira's Stabat Mater, op.240: an approach between music and rhetoric" (2005). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3618. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3618 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. A CONDUCTOR’S ANALYSIS OF AMARAL VIEIRA’S STABAT MATER, OP. 240: AN APPROACH BETWEEN MUSIC AND RHETORIC A Monograph Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The School of Music by Vladimir A. Pereira Silva B.M.E., Universidade Federal da Paraíba, 1992 M. Mus., Universidade Federal da Bahia, 1999 May, 2005 © Copyright 2005 Vladimir A. Pereira Silva All rights reserved ii In principio erat Verbum et Verbum erat apud Deum et Deus erat Verbum. Evangelium Secundum Iohannem, Caput 1:1 iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This dissertation would have not been possible without the support of many people and institutions throughout the last several years, and I would like to thank them all for a great graduate school experience. -

EMR 12386 Stabat Mater WB

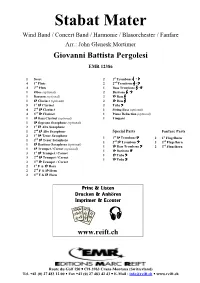

Stabat Mater Wind Band / Concert Band / Harmonie / Blasorchester / Fanfare Arr.: John Glenesk Mortimer Giovanni Battista Pergolesi EMR 12386 st 1 Score 2 1 Trombone + st nd 4 1 Flute 2 2 Trombone + nd 4 2 Flute 1 Bass Trombone + 1 Oboe (optional) 2 Baritone + 1 Bassoon (optional) 2 E Bass 1 E Clarinet (optional) 2 B Bass 5 1st B Clarinet 2 Tuba 4 2nd B Clarinet 1 String Bass (optional) 4 3rd B Clarinet 1 Piano Reduction (optional) 1 B Bass Clarinet (optional) 1 Timpani 1 B Soprano Saxophone (optional) st 2 1 E Alto Saxophone 1 2nd E Alto Saxophone Special Parts Fanfare Parts st 2 1 B Tenor Saxophone 1 1st B Trombone 2 1st Flugelhorn 1 2nd B Tenor Saxophone 1 2nd B Trombone 2 2nd Flugelhorn 1 E Baritone Saxophone (optional) 1 B Bass Trombone 2 3rd Flugelhorn 1 E Trumpet / Cornet (optional) 1 B Baritone 3 1st B Trumpet / Cornet 1 E Tuba 3 2nd B Trumpet / Cornet 1 B Tuba 3 3rd B Trumpet / Cornet 2 1st F & E Horn 2 2nd F & E Horn 2 3rd F & E Horn Print & Listen Drucken & Anhören Imprimer & Ecouter≤ www.reift.ch Route du Golf 150 CH-3963 Crans-Montana (Switzerland) Tel. +41 (0) 27 483 12 00 Fax +41 (0) 27 483 42 43 E-Mail : [email protected] www.reift.ch DISCOGRAPHY Baroque Splendour Volume 2 Track Titel / Title Time N° EMR N° EMR N° (Komponist / Composer) Blasorchester Brass Band Concert Band 1 Rondeau (Les Indes Galantes) (Rameau) 1’51 EMR 12220 EMR 32124 2 Le Basque (Marais) 2’24 EMR 12611 EMR 32125 3 Tambourin (Dardanus) (Rameau) 2’29 EMR 12213 EMR 32126 4 Marche Royale (Lully) 2’18 EMR 12226 EMR 9855 5 Symphonies pour -

Publicity Book

JORY VINIKOUR conductor, harpsichordist Jory Vinikour is recognized as one of the outstanding harpsichordists of his generation. A highly diversified career brings him to the world!s most important festivals and concert halls as recital and concerto soloist, partner to several of today!s finest singers, and increasingly as a conductor. Born in Chicago, Jory Vinikour came to Paris on a scholarship from the Fulbright Foundation to study with Huguette Dreyfus and Kenneth Gilbert. First Prizes in the International Harpsichord Competitions of Warsaw (1993) and the Prague Spring Festival (1994) brought him to the public!s attention, and he has since appeared in festivals and concert series such as Besançon Festival, Deauville, Nantes, Monaco, Cleveland Museum of Art, Miami Bach Festival, Indianapolis Early Music Festival, etc. A concerto soloist with a repertoire ranging from Bach to Nyman, passing by Poulenc!s Concert Champêtre, Jory Vinikour has performed as soloist with leading orchestras including Rotterdam Philharmonic, Flanders Opera Orchestra, Orchestre de la Suisse Romande, Lausanne Chamber Orchestra, Philharmonic of Radio France, Ensemble Orchestral de Paris, and Moscow Chamber Orchestra with conductors such as Armin Jordan, Marc Minkowski, Marek Janowski, Constantine Orbelian, John Nelson, and Fabio Luisi. He recorded Frank Martin!s Petite Symphonie Concertante with the Lausanne Chamber Orchestra under the direction of Armin Jordan (Suisse Romande, 2005), and also performed the Harpsichord Concerto by the same composer with the Symphony Orchestra of the MDR in Leipzig!s Gewandhaus under the direction of Martin Haselböck in January of 2003. A complete musician, Mr. Vinikour is gaining a reputation as a conductor (studies with Vladimir Kin and Denise Ham) and music director. -

Antonín Dvorák • Requiem

Antonín Dvorˇák • Requiem Ilse Eerens – Bernarda Fink – Maximilian Schmitt – Nathan Berg Collegium Vocale Gent – Royal Flemish Philharmonic Philippe Herreweghe Tracklist – p. 5 English – p. 8 Français – p. 13 Deutsch – p. 19 Nederlands – p. 25 Sung Texts – p. 30 Antonín Dvorˇák (1841-1904) Requiem, Op. 89 Ilse Eerens soprano Bernarda Fink alto Maximilian Schmitt tenor Nathan Berg bass Collegium Vocale Gent Royal Flemish Philharmonic Philippe Herreweghe Recording: April 28-30, 2014, deSingel, Antwerp — Sound Engineer: Markus Heiland (Tritonus) — Editing: Markus Heiland & Andreas Neubronner (Tritonus) — Recording Producer, Mastering: Andreas Neubronner (Tritonus) — Liner Notes: Tom Janssens — Cover picture: photo Michel Dubois (Courtesy Dubois Friedland) — Photographs Philippe Herreweghe: Michiel Hendryckx — Design: Casier/Fieuws — Executive Producer: Aliénor Mahy MENU CD 1 INTROITUS [1] Requiem æternam – Kyrie eleison (Soli and Chorus)........................................................10’44 GRADUALE [2] Requiem æternam (Soprano and Chorus)......................................................................04’38 SEQUENTIA [3] Dies iræ (Chorus).......................................................................................................02’28 [4] Tuba mirum (Soli and Chorus) ....................................................................................08’35 [5] Quid sum miser (Soli and Chorus) ...............................................................................06’02 [6] Recordare, Jesu pie (Soli) .............................................................................................07’03 -

Download Booklet

552139-40bk VBO Dvorak 16/8/06 9:48 PM Page 8 CD1 1 Carnival Overture, Op. 92 . 9:29 2 Humoresques, Op. 101 No. 7 Poco lento e grazioso in G flat major . 2:51 3 String Quartet No. 12 in F major, Op. 96 ‘American’ III. Molto vivace . 4:01 4 Symphony No. 8 in G major, Op. 88 III. Allegretto grazioso – Molto vivace . 5:45 5 7 Gipsy Melodies ‘Zigeunerlieder’ – song collection, Op. 55 No. 4 Songs my mother taught me . 2:47 6 Serenade for Strings in E major, Op.22 I. Moderato . 4:10 7 Slavonic Dances, Op. 46 No. 2 in E minor . 4:40 8 Piano Trio in F minor ‘Dumky’, Op. 90 III. Andante – Vivace non troppo . 5:56 9 Symphony No. 7 in D minor, Op. 70 III. Scherzo: Vivace – Poco meno messo . 7:47 0 Violin Sonatina in G major, Op. 100 II. Larghetto . 4:33 ! Slavonic Dances, Op. 72 No. 2 in E minor . 5:29 @ Rusalka, Op. 114 O, Silver Moon . 5:52 # The Noon Witch . 13:04 Total Timing . 77:10 CD2 1 Slavonic Dances, Op. 46 No. 1 in C major . 3:46 2 Stabat Mater, Op. 58 Fac ut portem Christi mortem . 5:13 3 Serenade for Wind, Op.44 I. Moderato, quasi marcia . 3:51 4 Cello Concerto in B minor, Op. 104 II. Adagio ma non troppo . 12:29 5 Piano Quintet in A major, Op. 81 III. Scherzo (Furiant) – Molto vivace . 4:06 6 Czech Suite, Op. 39 II. Polka . 4:49 7 Legends, Op. -

Thursday Playlist

February 14, 2019: (Full-page version) Close Window “Imagination creates reality.” —Richard Wagner Start Buy CD Stock Program Composer Title Performers Record Label Barcode Time online Number Sleepers, 00:01 Buy Now! Humperdinck Overture ~ Hansel and Gretel Symphony Nova Scotia/Tintner CBC 5167 059582516720 Awake! 00:10 Buy Now! Mozart Piano Concerto No. 25 in C, K. 503 Argerich/Orchestra Mozart/Abbado DG 479 1033 028947910336 00:41 Buy Now! Prokofiev Romeo and Juliet: Suite No. 3, Op. 101 Suisse Romande Orchestra/Jordan Erato 45817 022924581724 01:00 Buy Now! Sibelius Night Ride and Sunrise, Op. 55 Philharmonia Orchestra/Rattle EMI 47006 N/A London 01:16 Buy Now! Mendelssohn Octet in E flat, Op. 20 London Concertante 0722 5060055390124 Concertante 01:48 Buy Now! Vivaldi Concerto in A minor for 2 Violins, Op. 3 No. 8 I Musici Philips 412 128 02894121282 02:01 Buy Now! Delibes Les filles de Cadix Fleming/Philharmonia/Lang-Lessing Decca B0019033 0289478510703 02:05 Buy Now! Paine Larghetto and Humoreske, Op. 32 Silverstein/Eskin/Eskin Northeastern 219 n/a 02:23 Buy Now! Haydn, M. Symphony No. 23 in D Bournemouth Sinfonietta/Farberman MMG 10026 04716300262 Concerto No. 3 in F for Two Wind Ensembles and 02:41 Buy Now! Handel English Concert/Pinnock Archiv 415 129 028941512925 Strings 03:00 Buy Now! Beethoven Leonore Overture No. 1 Atlanta Symphony/Levi Telarc 80358 089408035821 03:10 Buy Now! Mozart Piano Quartet No. 2 in E flat, K. 493 Stern/Katims/Schneider/Istomin Sony 64516 074646451625 03:37 Buy Now! Rubbra String Quartet No.1 in F minor, Op. -

Chamber Orchestra and Concert Choir Glenn Block, Director

Illinois State University ISU ReD: Research and eData School of Music Programs Music 3-29-2013 Student Ensemble: Chamber Orchestra and Concert Choir Glenn Block, Director Karyl K. Carlson, Director Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/somp Part of the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Block,, Glenn Director and Carlson,, Karyl K. Director, "Student Ensemble: Chamber Orchestra and Concert Choir" (2013). School of Music Programs. 480. https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/somp/480 This Concert Program is brought to you for free and open access by the Music at ISU ReD: Research and eData. It has been accepted for inclusion in School of Music Programs by an authorized administrator of ISU ReD: Research and eData. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Illinois State University Chamber Orchestra Illinois State University College of Fine Arts School of Music Violin I Bassoon Ramiro Miranda, Concertmaster Katie Spitler * Maggie Watts Michael Sullivan Natalie Stawarski Gabrielle VanDril Horn Christine Hansen * Violin II Joshua Hernday Chloe Hawkins * Justin Johnson Illinois State University Chelsea Rilloraza Tyler Sutton Julia Heeren Chamber Orchestra Andrada Pteanc Trumpet Glenn Block, Music Director and Conductor Vallerie Villa Shauna Bracken * Tristan Burgmann Viola Illinois State University Matt White* Trombone Caroline Argenta Riley Leitch * Concert Choir Gillian Borth Jordan Harvey Abigail Dreher Karyl K. Carlson, Music Director and Conductor Bass Trombone Cello Grant Unnerstall* -

Stabat Mater 1831/32 Original Version with Sections by Giovanni Tadolini Giovanna D’Arco – Cantata

Gioachino ROSSINI Stabat Mater 1831/32 Original version with sections by Giovanni Tadolini Giovanna d’Arco – Cantata Majella Cullagh • Marianna Pizzolato José Luis Sola • Mirco Palazzi Camerata Bach Choir, Poznań • Württemberg Philharmonic Orchestra Antonino Fogliani Gioachino Rossini (1792-1868) * and Giovanni Tadolini (1789-1872) ** Gioachino Rossini Stabat Mater Giovanna d’Arco (°) 1831/32 original version, **orchestrated by Antonino Fogliani (b. 1976) ............................ 56:07 Solo cantata (1832) with piano accompaniment orchestrated by Marco Taralli (b. 1967) .....15:13 $ 1 I. Introduction: Stabat Mater dolorosa * ........................................................... 8:35 I. Recitativo: È notte, e tutto addormentato è il mondo ................................. 4:44 (Soloists and Chorus) (Andantino) % 2 II. Aria: Cujus animam gementem ** .................................................................. 2:40 II. Aria: O mia madre, e tu frattanto la tua figlia cercherai .............................. 3:29 (Tenor) (Andantino grazioso) ^ 3 III. Duettino: O quam tristis et afflicta ** ............................................................. 3:34 III. Recitativo: Eppur piange. Ah! repente qual luce balenò ............................ 1:14 (Soprano and Mezzo-soprano) (Allegro vivace – Allegretto) & 4 IV. Aria: Quae moerebat et dolebat ** ................................................................. 2:51 IV. Aria: Ah, la fiamma che t’esce dal guardo già m’ha tocca ......................... 5:46 (Bass) (Allegro vivace -

“Stabat Mater” Week 17 Dvorák

2018–19 season andris nelsons bostonmusic director symphony orchestra week 17 dvo rˇ ák “stabat mater” Season Sponsors seiji ozawa music director laureate bernard haitink conductor emeritus supporting sponsorlead sponsor supporting sponsorlead thomas adès artistic partner Better Health, Brighter Future There is more that we can do to help improve people’s lives. Driven by passion to realize this goal, Takeda has been providing society with innovative medicines since our foundation in 1781. Today, we tackle diverse healthcare issues around the world, from prevention to care and cure, but our ambition remains the same: to find new solutions that make a positive difference, and deliver better medicines that help as many people as we can, as soon as we can. With our breadth of expertise and our collective wisdom and experience, Takeda will always be committed to improving the Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited future of healthcare. www.takeda.com Takeda is proud to support the Boston Symphony Orchestra Table of Contents | Week 17 7 bso news 1 5 on display in symphony hall 16 bso music director andris nelsons 18 the boston symphony orchestra 2 3 a brief history of the bso 29 casts of character: the symphony statues by caroline taylor 3 6 this week’s program Notes on the Program 38 The Program in Brief… 39 Dvoˇrák “Stabat Mater” 53 To Read and Hear More… Guest Artists 55 Rachel Willis-Sørensen 57 Violeta Urbana 59 Dmytro Popov 61 Matthew Rose 63 Tanglewood Festival Chorus 65 James Burton 7 0 sponsors and donors 80 future programs 82 symphony hall exit plan 8 3 symphony hall information the friday preview on march 1 is given by bso director of program publications marc mandel. -

Cohesion of Composer and Singer: the Female Singers of Poulenc

COHESION OF COMPOSER AND SINGER: THE FEMALE SINGERS OF POULENC DOCUMENT Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Susan Joanne Musselman, B.M., M.M. ***** The Ohio State University 2007 Document Committee: J. Robin Rice, Adviser Approved by: Hilary Apfelstadt Wayne Redenbarger ________________________ Adviser Graduate Program in Music Copyright by Susan Joanne Musselman 2007 ABSTRACT Every artist’s works spring from an aspiring catalyst. One’s muses can range from a beloved city to a spectacular piece of music, or even a favorite time of year. Francis Poulenc’s inspiration for song-writing came from the high level of intimacy he had with his close friends. They provided the stimulation and encouragement needed for a lifetime of composition. There is a substantial amount of information about Francis Poulenc’s life and works available. We are fortunate to have access to his own writings, including a diary of his songs, an in-depth interview with a close friend, and a large collection of his correspondence with friends, fellow composers, and his singers. It is through these documents that we not only glean knowledge of this great composer, but also catch a glimpse of the musical accuracy Poulenc so desired in the performance of his songs. A certain amount of scandal surrounded Poulenc during his lifetime and even well after his passing. Many rumors existed involving his homosexuality and his relationships with other male musicians, as well as the possible fathering of a daughter. The primary goal of this document is not to unearth any hidden innuendos regarding his personal life, however, but to humanize the relationships that Poulenc had with so many of his singers.