'EQUALITY NOW!': RACE, RACISM and RESISTANCE in 1970S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Core 1..180 Hansard (PRISM::Advent3b2 15.00)

House of Commons Debates VOLUME 146 Ï NUMBER 165 Ï 1st SESSION Ï 41st PARLIAMENT OFFICIAL REPORT (HANSARD) Friday, October 19, 2012 Speaker: The Honourable Andrew Scheer CONTENTS (Table of Contents appears at back of this issue.) 11221 HOUSE OF COMMONS Friday, October 19, 2012 The House met at 10 a.m. terrorism and because it is an unnecessary and inappropriate infringement on Canadians' civil liberties. New Democrats believe that Bill S-7 violates the most basic civil liberties and human rights, specifically the right to remain silent and the right not to be Prayers imprisoned without first having a fair trial. According to these principles, the power of the state should never be used against an individual to force a person to testify against GOVERNMENT ORDERS himself or herself. However, the Supreme Court recognized the Ï (1005) constitutionality of hearings. We believe that the Criminal Code already contains the necessary provisions for investigating those who [English] are involved in criminal activity and for detaining anyone who may COMBATING TERRORISM ACT present an immediate threat to Canadians. The House resumed from October 17 consideration of the motion We believe that terrorism should not be fought with legislative that Bill S-7, An Act to amend the Criminal Code, the Canada measures, but rather with intelligence efforts and appropriate police Evidence Act and the Security of Information Act, be read the action. In that context one must ensure that the intelligence services second time and referred to a committee. and the police forces have the appropriate resources to do their jobs. -

Mortgage Defaulting Premiers Ask Caution

: P~OV]:N~ r_,-~ ' , : ,.r~.', ..,.....,~ ''~," PARLI~T.-:;: ' ~';,'~ ;3 YX(II'O!~[A (J L; Winter• food hikes ar e on th e way annualOTTAWA autumn (CP) drop in foodThe level at the same time last The index is based on a mers to raise fluid milk beef prices. This puts the they jumped by 2.8 per cent would be greater if apples The beard recommends year. survey of a typical basket of . prices by two cents a quart beef component of the index during October. prices has. ended, says the . The board blames the in- 68grocery items in 60 super- Oct. 1. had not dropped in price by consumers take advantage 4l.S per cent higher thanone Tl~e board blames ad- 10.4 per cent as the new federal anti-inflation board, crease on higher prices for markets across Canada. Although retail beef prices of cheap apples to bring In its monthly report on beef, pork, oranges and most Milk costs were up one per year ago. vanees in the price of ira- harvest came on the market. down the cost of its weekly have not climbed back to Pork prices have also risen ported oranges-combined Fresh vegetabJe prices food prices, the board says fresh vegetables. The only cent during October. The zheir mid-summer peak nutritious diet. its foodat-home price index ' bright spots in the food doard attributed this in- substantially, partly because with the low value of the were up 3.6 per cent. This The diet, which fulfills all prices, there was a 5.8-per- consumers are buying pork Canadian dollar-- for most increase also was attributed L Jumped during October by survey were a decline in the crease to a decision of the cent jump in prices for the nutrition requirements for a 1.9 per cent. -

African and Caribbean Philanthropy in Ontario

AT A GLANCE 1 000 000 000+Total population of Africa 40 000 000+Total population of the Caribbean 1 000 000+ Population of Canadians who identify as Black 85 Percentage of the Caribbean population who are Christian African 45 Percentage of Africans who identify as Muslim and Caribbean 40 Percentage of Africans who identify as Christian Philanthropy 85 Percentage of Jamaican-Canadians living in Ontario in Ontario In October 2013, the Association of Fundraising Professionals Foundation for Philanthropy – Canada hosted a conference that brought together charity leaders, donors and volunteers to explore TERMINOLOGY the philanthropy of the African and Caribbean CASE STUDY communities in Ontario. Here is a collection of Ubuntu: A pan-African philosophy or In 1982, the Black Business and insights from the conference and beyond. belief in a universal bond of sharing Professional Association (BBPA) wanted that connects all humans. to recognize the achievements of the six Black Canadian athletes who excelled at the Commonwealth Games that year. Organizers of the dinner invited Harry Jerome, Canada’s premiere track and field WISE WORDS athlete of the 1960s, to be the keynote “Ontario’s African and Caribbean communities are very distinct – both with respect to their speaker. Harry Jerome tragically died just histories and their relationship with Canada. The mistake the philanthropic sector could prior to the event and it was decided to turn the occasion into a tribute to him. The first easily make is treating these groups as a single, homogeneous community. What is most Harry Jerome Awards event took place on remarkable is the concept of ubuntu – or “human kindness” – and that faith in both of these March 5, 1983 and is now an annual national communities is very strong and discussed openly. -

Toronto Has No History!’

‘TORONTO HAS NO HISTORY!’ INDIGENEITY, SETTLER COLONIALISM AND HISTORICAL MEMORY IN CANADA’S LARGEST CITY By Victoria Jane Freeman A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History University of Toronto ©Copyright by Victoria Jane Freeman 2010 ABSTRACT ‘TORONTO HAS NO HISTORY!’ ABSTRACT ‘TORONTO HAS NO HISTORY!’ INDIGENEITY, SETTLER COLONIALISM AND HISTORICAL MEMORY IN CANADA’S LARGEST CITY Doctor of Philosophy 2010 Victoria Jane Freeman Graduate Department of History University of Toronto The Indigenous past is largely absent from settler representations of the history of the city of Toronto, Canada. Nineteenth and twentieth century historical chroniclers often downplayed the historic presence of the Mississaugas and their Indigenous predecessors by drawing on doctrines of terra nullius , ignoring the significance of the Toronto Purchase, and changing the city’s foundational story from the establishment of York in 1793 to the incorporation of the City of Toronto in 1834. These chroniclers usually assumed that “real Indians” and urban life were inimical. Often their representations implied that local Indigenous peoples had no significant history and thus the region had little or no history before the arrival of Europeans. Alternatively, narratives of ethical settler indigenization positioned the Indigenous past as the uncivilized starting point in a monological European theory of historical development. i i iii In many civic discourses, the city stood in for the nation as a symbol of its future, and national history stood in for the region’s local history. The national replaced ‘the Indigenous’ in an ideological process that peaked between the 1880s and the 1930s. -

Seven Vie for Three Council Seats the Daily Herald

!,E,]I~I.,'~'/.~ I.~:~?: ~:Y, C~:£P.77178 : . ,:.. ,'.". :.. • ~,~ ..., :.. V8V-l>;~ Mayor acclaimed t~.rry Duffas John McCormac Lily Mielson Alan Sontar Seven vie for three council seats '-: ": .Dave Maroney Jack Tals/ra Doug Mumford Helmut Giesbreeht BY DONNA VALLIERES years. No one opposed Helmut Giesbrecht and two years, has said he Gerry Duffus, a former and varied issues but must of Skeenaview Lodge. assist the present ad- ., :.HERALDSTAFF WRITER Maroney for the mayor's Jack Talstra, also filed wants to continue because alderman on Terrace continue the important Lily Mielsen, lists herself ministration m becoming seat, so he will be elected by. nomination . papers he's practically/an old hand council who describes functions of looking after on her nomination papers- more efficient and thus put '. "Th_i_ngs .have definitely as a domestic engineer. She to better use the tax ~d~d up oa .the local acclamation. yesterday. at council business, himself as a property sewage, drainage, roads "electina scene with a sur- As for the ~est of council, Giesbrecht, a teacher with and sxdewalks. said "you must get in- dollar." seven persons have an- two years experience on Painter John MacCorrnac volved" in order to un- A more aggressive ~Prldng,vnsh of candidates campaign should be m effect declaring their intentions nounced their bids for three council, has stated he will will try for the first time to derstand an issue." aldermanic seats up for seek re-election because of. More election news enter municipal politics as • A resident of Terrace to r~luce the big overhead ~a~lnd~Y,f~ nomination since 1959, Mielsea said she on the arena and swimming • _ positions on grabs this term. -

Rethinking Toronto's Middle Landscape: Spaces of Planning, Contestation, and Negotiation Robert Scott Fiedler a Dissertation S

RETHINKING TORONTO’S MIDDLE LANDSCAPE: SPACES OF PLANNING, CONTESTATION, AND NEGOTIATION ROBERT SCOTT FIEDLER A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY GRADUATE PROGRAM IN GEOGRAPHY YORK UNIVERSITY TORONTO, ONTARIO May 2017 © Robert Scott Fiedler, 2017 Abstract This dissertation weaves together an examination of the concept and meanings of suburb and suburban, historical geographies of suburbs and suburbanization, and a detailed focus on Scarborough as a suburban space within Toronto in order to better understand postwar suburbanization and suburban change as it played out in a specific metropolitan context and locale. With Canada and the United States now thought to be suburban nations, critical suburban histories and studies of suburban problems are an important contribution to urbanistic discourse and human geographical scholarship. Though suburbanization is a global phenomenon and suburbs have a much longer history, the vast scale and explosive pace of suburban development after the Second World War has a powerful influence on how “suburb” and “suburban” are represented and understood. One powerful socio-spatial imaginary is evident in discourses on planning and politics in Toronto: the city-suburb or urban-suburban divide. An important contribution of this dissertation is to trace out how the city-suburban divide and meanings attached to “city” and “suburb” have been integral to the planning and politics that have shaped and continue to shape Scarborough and Toronto. The research employs an investigative approach influenced by Michel Foucault’s critical and effective histories and Bent Flyvbjerg’s methodological guidelines for phronetic social science. -

Summary by Quartile.Xlsx

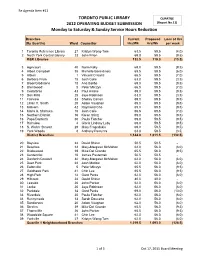

Re Agenda Item #11 TORONTO PUBLIC LIBRARY QUARTILE 2012 OPERATING BUDGET SUBMISSION (Report No.11) Monday to Saturday & Sunday Service Hours Reduction Branches Current Proposed Loss of Hrs (By Quartile) Ward Councillor Hrs/Wk Hrs/Wk per week 1 Toronto Reference Library 27 Kristyn Wong-Tam 63.5 59.5 (4.0) 2 North York Central Library 23 John Filion 69.0 59.5 (9.5) R&R Libraries 132.5 119.0 (13.5) 3 Agincourt 40 Norm Kelly 69.0 59.5 (9.5) 4 Albert Campbell 35 Michelle Berardinetti 65.5 59.5 (6.0) 5 Albion 1 Vincent Crisanti 66.5 59.5 (7.0) 6 Barbara Frum 15 Josh Colle 63.0 59.5 (3.5) 7 Bloor/Gladstone 18 Ana Bailão 69.0 59.5 (9.5) 8 Brentwood 5 Peter Milczyn 66.5 59.5 (7.0) 9 Cedarbrae 43 Paul Ainslie 69.0 59.5 (9.5) 10 Don Mills 25 Jaye Robinson 63.0 59.5 (3.5) 11 Fairview 33 Shelley Carroll 69.0 59.5 (9.5) 12 Lillian H. Smith 20 Adam Vaughan 69.0 59.5 (9.5) 13 Malvern 42 Raymond Cho 69.0 59.5 (9.5) 14 Maria A. Shchuka 15 Josh Colle 66.5 59.5 (7.0) 15 Northern District 16 Karen Stintz 69.0 59.5 (9.5) 16 Pape/Danforth 30 Paula Fletcher 69.0 59.5 (9.5) 17 Richview 4 Gloria Lindsay Luby 69.0 59.5 (9.5) 18 S. Walter Stewart 29 Mary Fragedakis 69.0 59.5 (9.5) 19 York Woods 8 AAnthonynthony Perruzza 63.0 59.5 ((3.5)3.5) District Branches 1,144.0 1,011.5 (132.5) 20 Bayview 24 David Shiner 50.5 50.5 - 21 Beaches 32 Mary-Margaret McMahon 62.0 56.0 (6.0) 22 Bridlewood 39 Mike Del Grande 65.5 56.0 (9.5) 23 Centennial 10 James Pasternak 50.5 50.5 - 24 Danforth/Coxwell 32 Mary-Margaret McMahon 62.0 56.0 (6.0) 25 Deer Park 22 Josh Matlow 62.0 56.0 (6.0) -

Tridel.Com INSERT FRONT 8 - 10.5” X 10.5”

INSERT FRONT 7 - 10.5” x 10.5” Prices and specifications are subject to change without notice. Illustrations are artist’s concept only. Building and view not to scale. Tridel®, Tridel Built for Life®, Tridel Built Green. Built for Life.® are registered trademarks of Tridel and used under license. ©Tridel 2015. All rights reserved. E.&O.E. May 2015. tridel.com INSERT FRONT 8 - 10.5” x 10.5” Prices and specifications are subject to change without notice. Illustrations are artist’s concept only. Building and view not to scale. Tridel®, Tridel Built for Life®, Tridel Built Green. Built for Life.® are registered trademarks of Tridel and used under license. ©Tridel 2015. All rights reserved. E.&O.E. May 2015. tridel.com INSERT FRONT 1 - 10.5” x 10.5” Prices and specifications are subject to change without notice. Illustrations are artist’s concept only. Building and view not to scale. Tridel®, Tridel Built for Life®, Tridel Built Green. Built for Life.® are registered trademarks of Tridel and used under license. ©Tridel 2015. All rights reserved. E.&O.E. May 2015. tridel.com INSERT BACK 1 - 10.5” x 10.5” Tridel is breathing new life into this prime downtown neighbourhood. SQ2 is the next stage in an incredible, master planned revitalization that will reinforce Alexandra Park’s status as a centre of culture and creativity. DiSQover a fresh take on life in the city. DENISON AVENUE RANDY PADMORE PARK AUGUSTA AVENUE AUGUSTA SQUARE CENTRAL PARK VANAULEY WALK VANAULEY STREET QUEEN STREET WEST NORTH PARK DUNDAS STREET WEST BASKETBALL COURTS CAMERON STREET SPADINA AVENUE INSERT FRONT 14 - 10.5” x 10.5” Cyclemania Christie Pits Qi Natural Saving Gigi Park Food Vince Gasparros The Bickford Boulevard Park Ici Bistro Café Harbord St. -

Self Guided Tour

The Toronto Ghosts & Hauntings Research Society Present s… About This Document: Since early October of 1997, The Toronto Ghosts and Hauntings Research Society has been collecting Toronto’s ghostly legends and lore for our website and sharing the information with anyone with an interest in things that go bump in the night… or day… or any time, really. If it’s ghostly in nature, we try to stay on top of it. One of the more popular things for a person with a passion for all things spooky is to do a “ghost tour”… which is something that our group has never really offered and never planned to do… but it is something we get countless requests about especially during the Hallowe’en season. Although we appreciate and understand the value of a good guided ghost tour for both the theatrical qualities and for a fun story telling time and as such, we are happy to send people in Toronto to Richard Fiennes-Clinton at Muddy York Walking Tours (who offers the more theatrical tours focusing on ghosts and history, see Image Above Courtesy of Toronto Tourism www.muddyyorktours.com) We do also understand that at Hallowe’en, these types of tours can Self Guided Walking Tour of fill up quickly and leave people in the lurch. Also, there are people that cannot make time for these tours because of scheduling or other commitments. Another element to consider is that we know there are Downtown Toronto people out there who appreciate a more “DIY” (do it yourself) flavour for things… so we have developed this booklet… This is a “DIY” ghost tour… self guided… from Union Station to Bloor Street…. -

Fighting in the Italian Campaign Down But

Veterans’Veterans’ WeekWeek SSpecialpecial EditionEdition - NovemberNovember 55 toto 11, 11, 2016 2019 Fighting in the Italian Campaign Down but One of Canada’s most important not out military efforts during the Second World War was the Italian Campaign. Sergeant Daniel J. MacDonald of Our troops’ first action there came Prince Edward Island served with during the Allied invasion of Sicily on the Cape Breton Highlanders in July 10, 1943, and Canadians played a Italy during the Second World key role in pushing enemy forces from War. He was badly wounded during this hot and dusty Mediterranean fighting at the Senio River on island. Their next task was attacking December 21, 1944, losing his left mainland Italy and our soldiers came arm and leg when a German shell ashore there on September 3, 1943. exploded nearby. MacDonald would not let these injuries derail the rest Italy was a challenging place to fight. of his life, however, and he returned Much of the country is mountainous home to PEI where he farmed, got with many deep valleys cut by rivers. married and raised seven children. The climate could be harsh, with He was elected to the provincial scorching summers and surprisingly Museum War Canadian Image: legislature in 1962 and later entered cold winters. The German defenders German Anti-Tank Position – a war painting by Lawren P. Harris depicting fighting in Italy. federal politics, becoming the were skilled and used the terrain to Minister of Veterans Affairs in the 1970s before passing away in 1980. their advantage, with our soldiers remembered by Canadian Veterans More than 93,000 Canadians would often facing heavy fire from the hills of the Italian Campaign today. -

Sec 2-Core Circle

TRANSFORMATIVE IDEA 1. THE CORE CIRCLE Re-imagine the valleys, bluffs and islands encircling the Downtown as a fully interconnected 900-hectare immersive landscape system THE CORE CIRLE 30 THE CORE CIRLE PUBLIC WORK 31 TRANSFORMATIVE IDEA 1. THE CORE CIRCLE N The Core Circle re-imagines the valleys, bluffs and islands E encircling the Downtown as a fully connected 900-hectare immersive landscape system W S The Core Circle seeks to improve and offer opportunities to reconnect the urban fabric of the Downtown to its surrounding natural features using the streets, parks and open spaces found around the natural setting of Downtown Toronto including the Don River Valley and ravines, Lake Ontario, the Toronto Islands, Garrison Creek and the Lake Iroquois shoreline. Connecting these large landscape features North: Davenport Road Bluff, Toronto, Canada will create a continuous circular network of open spaces surrounding the Downtown, accessible from both the core and the broader city. The Core Circle re- imagines the Downtown’s framework of valleys, bluffs and islands as a connected 900-hectare landscape system and immersive experience, building on Toronto’s strong identity as a ‘city within a park’ and providing opportunities to acknowledge our natural setting and connect to the history of our natural landscapes. East: Don River Valley Ravine and Rosedale Valley Ravine, Toronto, Canada Historically, the natural landscape features that form the Core Circle were used by Indigenous peoples as village sites, travelling routes and hunting and gathering lands. They are regarded as sacred landscapes and places for spiritual renewal. The Core Circle seeks to re-establish our connection to these landscapes. -

Accession No. 1986/428

-1- Liberal Party of Canada MG 28 IV 3 Finding Aid No. 655 ACCESSION NO. 1986/428 Box No. File Description Dates Research Bureau 1567 Liberal Caucus Research Bureau Briefing, Book - British Columbia, Vol. I July 1981 Liberal Caucus Research Bureau Briefing, Book - Saskatchewan, Vol. I and Sept. 1981 II Liberal Caucus Research Bureau Briefing, Book - Alberta, Vol. II May 20, 1981 1568 Liberal Caucus Research Bureau Briefing, Book - Manitoba, Vols. II and III 1981 Liberal caucus Research Bureau Briefing, Book - British Columbia, Vol. IV 1981 Elections & Executive Minutes 1569 Minutes of LPC National Executive Meetings Apr. 29, 1979 to Apr. 13, 1980 Poll by poll results of October 1978 By-Elections Candidates' Lists, General Elections May 22, 1979 and Feb. 18, 1980 Minutes of LPC National Executive Meetings June-Dec. 1981 1984 General Election: Positions on issues plus questions and answers (statements by John N. Turner, Leader). 1570 Women's Issues - 1979 General Election 1979 Nova Scotia Constituency Manual Mar. 1984 Analysis of Election Contribution - PEI & Quebec 1980 Liberal Government Anti-Inflation Controls and Post-Controls Anti-Inflation Program 2 LIBERAL PARTY OF CANADA MG 28, IV 3 Box No. File Description Dates Correspondence from Senator Al Graham, President of LPC to key Liberals 1978 - May 1979 LPC National Office Meetings Jan. 1976 to April 1977 1571 Liberal Party of Newfoundland and Labrador St. John's West (Nfld) Riding Profiles St. John's East (Nfld) Riding Profiles Burin St. George's (Nfld) Riding Profiles Humber Port-au-Port-St.