Triumph of the Spirit Study Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Katalog 1999

m u r 2 Grußwort o f 3 Vorwort 4 Fotoausstellung HOHE ZEIT – HOCHZEIT von Giorgio von Arb m 5 Werkschau Dennis O’Rourke l 911 9Hommage an Djibril Diop Mambéty i 15 Latino Cinema in den USA f 30 Israel: Ein Einwanderungsland Dokumentarfilme r 38 Brasilianische Dokumentar- und Ethnofilme e 43 Aktuelle Produktionen 199 7– 1999 g 61 Register: Filmtitel und RegisseurInnen r 62 Impressum u b i e r f Inhalt 1 freiburger film forum’ 99 Guten Ta g! Es ist das zweite Mal, daß die Stadt Freiburg das freiburger nicht nur dem Publikum, sondern auch den FilmerInnen und film forum – ethnologie und afrika/amerika/asien/ozeanien WissenschaftlerInnen, die wieder aus der ganzen Welt fördert. Es ist hervorgegangen aus dem seit 1985 bestehenden eingeladen sind und nach Freiburg kommen, vielfältige Anre - film forum freiburg . Es hat sich mittlerweile national wie inter - gungen und Denkanstöße gibt. national durchgesetzt. Ein Rückblick auf das letzte Festival über Himmelfahrt 1997, das sowohl vom Programm wie vom Wichtig ist aus kulturpolitischer Sicht, daß sich auch zu Publikumszuspruch her sehr erfolgreich war, untermauert die - diesem freiburger film forum wieder zahlreiche Kulturein - se Bewertung. richtungen in der Stadt zusammengeschlossen haben; die Stadt selbst ist einer langen Tradition folgend mit dem Adel - Die politische Bedeutung der »außereuropäischen« Sek - hausermuseum beteiligt, das eine Ausstellung des Schweizer tion des freiburger film forums liegt darin, den Blick eines Fotographen Giorgio von Arb zeigt. Es sind nicht nur die europäischen Betrachters für die Spezifik und die Eigenart knapper werdenden Mittel, die die einzelnen Institutionen zur afrikanischer, amerikanischer, asiatischer oder ozeanischer Zusammenarbeit bringen; immer stärker setzt sich die Einsicht Kulturen zu schärfen und gleichzeitig Verbindungslinien durch, daß die kulturelle Zukunft den Netzwerken gehört. -

Genocide, Memory and History

AFTERMATH GENOCIDE, MEMORY AND HISTORY EDITED BY KAREN AUERBACH AFTERMATH AFTERMATH GENOCIDE, MEMORY AND HISTORY EDITED BY KAREN AUERBACH Aftermath: Genocide, Memory and History © Copyright 2015 Copyright of the individual chapters is held by the chapter’s author/s. Copyright of this edited collection is held by Karen Auerbach. All rights reserved. Apart from any uses permitted by Australia’s Copyright Act 1968, no part of this book may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from the copyright owners. Inquiries should be directed to the publisher. Monash University Publishing Matheson Library and Information Services Building 40 Exhibition Walk Monash University Clayton, Victoria, 3800, Australia www.publishing.monash.edu Monash University Publishing brings to the world publications which advance the best traditions of humane and enlightened thought. Monash University Publishing titles pass through a rigorous process of independent peer review. www.publishing.monash.edu/books/agmh-9781922235633.html Design: Les Thomas ISBN: 978-1-922235-63-3 (paperback) ISBN: 978-1-922235-64-0 (PDF) ISBN: 978-1-876924-84-3 (epub) National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry: Title: Aftermath : genocide, memory and history / editor Karen Auerbach ISBN 9781922235633 (paperback) Series: History Subjects: Genocide. Genocide--Political aspects. Collective memory--Political aspects. Memorialization--Political aspects. Other Creators/Contributors: Auerbach, Karen, editor. Dewey Number: 304.663 CONTENTS Introduction ............................................... -

9629 Filmfest Program.Indd

FILM IN SYRACUSE 1 FILM IN SYRACUSE Special Letter From The Artistic Director, Owen Shapiro PEACE AND SOCIAL JUSTICE is the focus of this year’s Syracuse International Film Festival. In 2009 Le Moyne College initiated a festival showcase of films dealing with the theme of Peace and Social Justice, and since that time has sponsored and hosted this showcase. In 2012 this theme takes on even greater significance in light of the death of Bassel Shahade, a Graduate student in Syracuse University’s College of Visual and Performing Arts’ Film Program. Bassel was killed while training citizen journalists in his home country of Syria to document with video what was happening there. Bassel’s love for his people and desire to help them fight for political, social, and economic freedom led to his decision to take a leave from his studies in Syracuse. Bassel’s honesty, personal integrity, and love for peace and opportunity were acutely felt by all who knew him. He was a model fighter for peace and social justice. Peace and Social Justice when seen in terms of the individual’s right to equal opportunity and respect regardless of economic class, race, gender, sexual orientation, nationality or religion also must include a person’s physical and/or mental abilities or disabilities. In this sense, peace and social justice includes another long-standing feature of our festival - Imaging Disability in Film, a program created by the School of Education at Syracuse University. Peace and Social Justice is about equality, fairness, and equal opportunity, basic values of all major religions and of all democratic societies. -

Movies and Mental Illness Using Films to Understand Psychopathology 3Rd Revised and Expanded Edition 2010, Xii + 340 Pages ISBN: 978-0-88937-371-6, US $49.00

New Resources for Clinicians Visit www.hogrefe.com for • Free sample chapters • Full tables of contents • Secure online ordering • Examination copies for teachers • Many other titles available Danny Wedding, Mary Ann Boyd, Ryan M. Niemiec NEW EDITION! Movies and Mental Illness Using Films to Understand Psychopathology 3rd revised and expanded edition 2010, xii + 340 pages ISBN: 978-0-88937-371-6, US $49.00 The popular and critically acclaimed teaching tool - movies as an aid to learning about mental illness - has just got even better! Now with even more practical features and expanded contents: full film index, “Authors’ Picks”, sample syllabus, more international films. Films are a powerful medium for teaching students of psychology, social work, medicine, nursing, counseling, and even literature or media studies about mental illness and psychopathology. Movies and Mental Illness, now available in an updated edition, has established a great reputation as an enjoyable and highly memorable supplementary teaching tool for abnormal psychology classes. Written by experienced clinicians and teachers, who are themselves movie aficionados, this book is superb not just for psychology or media studies classes, but also for anyone interested in the portrayal of mental health issues in movies. The core clinical chapters each use a fabricated case history and Mini-Mental State Examination along with synopses and scenes from one or two specific, often well-known “A classic resource and an authoritative guide… Like the very movies it films to explain, teach, and encourage discussion recommends, [this book] is a powerful medium for teaching students, about the most important disorders encountered in engaging patients, and educating the public. -

Beverly-Hills-Chihuahua-Production

THIS MATERIAL IS ALSO AVAILABLE ONLINE AT http://www.wdsfilmpr.com © Disney Enterprises, Inc. All Rights Reserved. disney.com/chihuahua CAST Rachel . PIPER PERABO Sam Cortez . MANOLO CARDONA CREDITS WALT DISNEY PICTURES Aunt Viv . JAMIE LEE CURTIS Vasquez. JOSÉ MARÍA YAZPIK Presents Rafferty . MAURY STERLING Officer Ramirez . JESUS OCHOA BEVERLY HILLS Store Owner . EUGENIO DERBEZ Rangers . OMAR LEYVA CHIHUAHUA NAOMY ROMO Angela. ALI HILLIS A Blair. MARGUERITE MOREAU MANDEVILLE FILMS/ Bryan . NICK ZANO SMART ENTERTAINMENT Inn Keeper Lady. CARMEN VERA Production Shelter Director . GINA GALLEGO Desk Clerk . HIRAM VILCHEZ A Film by Bellman . ALBERTO REYES RAJA GOSNELL Doorman/ The Carthay . ENRIQUE CHAVERO Directed by . RAJA GOSNELL Doorman/ Screenplay by . ANALISA LABIANCO Baja Sur Hotel . ANDRES PARDAVE and JEFF BUSHELL Armand . JUAN CARLOS MARTIN Story by . JEFF BUSHELL Conductor . JUAN ANTONIO SALDAÑA Produced by. DAVID HOBERMAN Ring Announcer . SAL LÓPEZ TODD LIEBERMAN Museum Guide . GIOVANNA ACHA Produced by . JOHN JACOBS Desk Sergeant. FERNANDO MANZANO Executive Producer . STEVE NICOLAIDES Butler . RANDALL ENGLAND Director of Chic Owners . CLAUDIA CERVANTES Photography . PHIL MEHEUX, BSC LILLIAN LANGE Production Designer . BILL BOES Waiter . BRANDON KEENER Editor . SABRINA PLISCO, A.C.E. Dog Nanny . JACK PLOTNICK Costume Shaman Lady . MARY PAZ MATA Designer . MARIESTELA FERNANDEZ Poor Woman. MAYRA SERBULO Visual Effects Baja Sur Supervisor . MICHAEL J. MCALISTER Desk Clerk . MONTSERRAT DE LEON Co-Producer . RICARDO DEL RIO GALNARES Lady . BERENICE ROMERO Music Composed by . HEITOR PEREIRA Museum Music Supervisor . BUCK DAMON Security Guards . ANTONIO INFANTE Casting by . AMANDA MACKEY, C.S.A. TOMIHUATZI XELHUALTZI and CATHY SANDRICH GELFOND, C.S.A. Little Boy . ERICK FERNANDO CAÑETE Limo Driver . -

September / October

AMERICAN & INTERNATIONAL SOCIETIES FOR YAD VASHEM Vol. 44-No. 1 ISSN 0892-1571 September/October 2017-Tishri/Cheshvan 5778 AUSCHWITZ ARTIFACTS TO GO ON TOUR millionaires over this,’ I would object,” um, which is on the site of the former the trust of the board of the Auschwitz BY JOANNA BERENDT, said Rabbi Marvin Hier, who founded camp, in southern Poland. “We had museum, which was surprised to THE NEW YORK TIMES the Simon Wiesenthal Center, a been thinking about this for a long receive such a request from an exhi- Jewish human-rights organization. time, but we lacked the know-how.” bition company outside the museum ore than 72 years after the lib- “But if they’re making what is normal- Even though the Holocaust remains world. eration of Auschwitz, the first M ly considered to be a fair amount of a major focus of study by historians The museum demanded that the traveling exhibition about the Nazi profit since the final end is that hun- and is a staple of school curriculum in artifacts be kept secured at all times death camp will begin a journey later dreds of thousands of people maybe many countries, knowledge about the and that the exhibition comply with this year to 14 cities across Europe the museum’s strict conservation and North America, taking heart- requirements, including finding proper breaking artifacts to multitudes who transportation and storage, as well as have never seen such horror up choosing exhibition spaces with suffi- close. cient lighting and climate control. The endeavor is one of the most The museum also insisted that the high-profile attempts to educate and artifacts be presented in historical immerse young people for whom the context, especially because many Holocaust is a fading and ill-under- aspects of World War II are only stood slice of history. -

We Hope That You Enjoy These Stories of Five Remarkable but Very Different Greek Jews

jewish figures GREECE GREEK JEWISH PERSONALITIES / 1 We hope that you enjoy these stories of five remarkable but very different Greek Jews. One was a rabbi who helped turn Salonika (Thessaloniki) into one of the world’s great Jewish cities in the 16th century. Another split the community and indeed much of the Jewish world apart with his claim to be the messiah. You’ll also meet the queen of the Greek blues, a woman whose voice expressed the yearning and pain of the country’s poor and ignored. While Greece’s Jewish community suffered devastation during the Holocaust, we’ll pay tribute to two people who somehow fought their way through the inferno. One was the leader of an all-female unit of partisan fighters, the other a boxer who survived Auschwitz through his unquenchable determination and the force of his fists. RABBI SAMUEL DE MEDINA (1505-1589) Rabbi Samuel ben Moses de Medina was the major Jewish leader in Thessaloniki (Salonika) as that city became home to one of the world’s great Jewish communities. He helped make Salonika a dynamic and, in many ways, fiercely independent center of Sephardi culture and scholarship. His was a life marked by public achievement and personal tragedy. He was from a prominent rabbinical family that fled persecution in Portugal and Spain and dispersed around the Ottoman Empire. His parents came to Salonika, which in the 16th century was rapidly growing into a key port city with a mainly Jewish population. They died when Samuel was a child. He was raised and, as an adult, financially supported by his elder brother. -

9 April 2017 1 History of the Holocaust Dr. Stallbaumer-Beishline This Is

1 History of the Holocaust Dr. Stallbaumer-Beishline This is not a comprehensive list of Holocaust films, but most of these I have seen. This list includes select foreign language films. The Holocaust may refer narrowly to the extermination of European Jews or more broadly victims of Nazi racism; perpetrators; bystanders; and post-war trials and tribulations of survivors, perpetrators, or bystanders. The Holocaust may be used as a plotting device that explains character motivations which raises question about the potential use or abuse of history in film. The list is divided into films or movies (Filmography) and made for television films or episodes (TVography). Wikipedia maintains a useful list: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Holocaust_films organized chronologically into films and documentaries. Filmography1 Adam Resurrected Fictional account set in post-WWII Israel. Through flashbacks, the main character, Adam, revisits major transitions in his life Nazi Germany. It explores how Adam comes to terms with survivor’s guilt. 2008. Amen "During WWII SS officer Kurt Gerstein tries to inform Pope Pius XII about Jews being sent to concentration camps. Young Jesuit priest Riccardo Fontana gives him a hand." English subtitles. Dir. Costa-Gavras. 2002. Professor – DVD) The Assisi Underground "Based on the best-selling documentary novel, this film sheds light on the work done by the Catholic Church and the people of Assisi to rescue several hundred Italian Jews from Nazi execution following the German occupation of Italy in 1943." Dir. Alexander Ramati. 1985. Au Revoir Les Enfants (Goodbye, Children) "Based on Malle's own experiences in a French boarding school during the German occupation, this moving film documents the friendship between a 12-year-old Catholic boy and a Jewish youngster being sheltered at the school by a priest." French with English subtitles. -

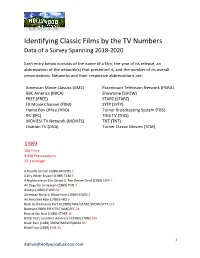

Identifying Classic Films by the TV Numbers Data of a Survey Spanning 2018-2020

Identifying Classic Films by the TV Numbers Data of a Survey Spanning 2018-2020 Each entry below consists of the name of a film, the year of its release, an abbreviation of the network(s) that presented it, and the number of its overall presentations. Networks and their respective abbreviations are: American Movie Classics (AMC) Paramount Television Network (PARA) BBC America (BBCA) Showtime (SHOW) FREE (FREE) STARZ (STARZ) FX Movie Channel (FXM) SYFY (SYFY) Home Box Office (HBO) Turner Broadcasting System (TBS) IFC (IFC) THIS TV (THIS) MOVIES! TV Network (MOVIES) TNT (TNT) Ovation TV (OVA) Turner Classic Movies (TCM) 1989 150 Films 4,958 Presentations 33,1 Average A Deadly Silence (1989) MOVIES 1 A Dry White Season (1989) TCM 4 A Nightmare on Elm Street 5: The Dream Child (1989) SYFY 7 All Dogs Go to Heaven (1989) THIS 7 Always (1989) STARZ 69 American Ninja 3: Blood Hunt (1989) STARZ 2 An Innocent Man (1989) HBO 5 Back to the Future Part II (1989) MAX/STARZ/SHOW/SYFY 272 Batman (1989) SYFY/TNT/AMC/IFC 24 Best of the Best (1989) STARZ 16 Bill & Ted’s Excellent Adventure (1989) STARZ 140 Black Rain (1989) SHOW/MOVIES/MAX 85 Blind Fury (1989) THIS 15 1 [email protected] Born on the Fourth of July (1989) MAX/BBCA/OVA/STARZ/HBO 201 Breaking In (1989) THIS 5 Brewster’s Millions (1989) STARZ 2 Bridge to Silence (1989) THIS 9 Cabin Fever (1989) MAX 2 Casualties of War (1989) SHOW 3 Chances Are (1989) MOVIES 9 Chattahoochi (1989) THIS 9 Cheetah (1989) TCM 1 Cinema Paradise (1989) MAX 3 Coal Miner’s Daughter (1989) STARZ 1 Collision -

Collection of Motion Picture Press Kits, 1939-Ongoing (Bulk 1970S-1990S)

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8wq05wj No online items Collection of Motion Picture Press Kits, 1939-ongoing (bulk 1970s-1990s) Processed by Library Special Collections staff; machine-readable finding aid created by Caroline Cubé. UCLA Library Special Collections Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA, 90095-1575 (310) 825-4988 [email protected] ©2014 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Collection of Motion Picture Press PASC 42 1 Kits, 1939-ongoing (bulk 1970s-1990s) Title: Collection of Motion Picture Press Kits Collection number: PASC 42 Contributing Institution: UCLA Library Special Collections Language of Material: English Physical Description: 90 linear ft.(187 boxes) Date: 1939-[ongoing] Abstract: The collection consists of press kits for primarily American released films and includes 3,700 plus film titles and represent a variety of film genres which were produced by studios such as Columbia Pictures, 20th Century Fox, MGM, Paramount, United Artists, Universal, and Warner Bros. Physical location: Stored off-site at SRLF. Advance notice is required for access to the collection. Please contact UCLA Library Special Collections for paging information. Restrictions on Access Open for research. STORED OFF-SITE AT SRLF. Advance notice is required for access to the collection. Please contact UCLA Library Special Collections for paging information. Note: boxes 181 and 187 are stored with the Accessioning Archivist and advance notice is required for access. Restrictions on Use and Reproduction Property rights to the physical object belong to the UC Regents. Literary rights, including copyright, are retained by the creators and their heirs. -

The Dove Foundation Grand Rapids, Michigan January 1999

PROFITABILITY STUDY of MPAA RATED MOVIES released during 1988 - 1997 Commissioned by The Dove Foundation Grand Rapids, Michigan January 1999 “Applause Applause! - there is this happy news that virtue is, if all too rarely, rewarded.” - Steve Allen - entertainer “This fascinating study proves that the real edge in Hollywood goes to competently crafted family entertainment.” - Michael Medved - film critic, radio talk show host “This study should encourage the production of more films intended for, and presumably suitable for the family.” - Robert Peters - President, Morality in Media “If Hollywood paid closer attention to its pocketbook, it might work to do more to lift up instead of drag down the culture it does so much to influence.” - Fr. Robert Sirico - President, Acton Institute for the Study of Religion and Liberty “The production of morally responsible G and PG-rated films should result in greater profitability for the industry while reducing the moral pollution of our culture.” - John Evans - President, Preview Family Movie Review The Dove Foundation - 245 State Street SE STE 104 - Grand Rapids MI 49503 (616) 454-5021 - Email: [email protected] - Web: http://www.dove.org Complete report can be downloaded at http://www.dove.org/reports TABLE OF CONTENTS DOVE FOUNDATION PRESS RELEASE Preface Dick Rolfe, CEO i COMMENTARIES Steve Allen iii Michael Medved iv Fr. Robert Sirico v Robert Peters v John Evans vi Studio Cover Letter viii SEIDMAN REPORT Page Executive Summary 1 Results 2 Conclusions 3 GRAPHS Figure Quantity of films produced -

Adventures of the Spirit

Adventures of the Spirit Adventures of the Spirit The Older Woman in the Works of Doris Lessing, Margaret Atwood, and Other Contemporary Women Writers Edited by Phyllis Sternberg Perrakis THE OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY PREss Columbus Copyright © 2007 by The Ohio State University. All rights reserved. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Adventures of the spirit : the older woman in the works of Doris Lessing, Margaret Atwood, and other contemporary women writers / edited by Phyllis Sternberg Perrakis. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references (p. ) and index. ISBN 978–0–8142–1064–2 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Canadian fiction—Women authors—History and criticism. 2. American fiction— Women authors—History and criticism. 3. Canadian fiction—20th century—History and criticism. 4. Canadian fiction—21st century—History and criticism. 5. American fiction—20th century—History and criticism. 6. American fiction—21st century— History and criticism. 7. Women and literature. 8. Self-consciousness (Awareness) in literature. 9. Older women in literature. 10. Old age in literature. I. Perrakis, Phyllis Sternberg. PR9188.A38 2007 810.9'9287—dc22 2007021566 This book is available in the following editions: Cloth (ISBN 978–0–8142–1064–2) CD-ROM (ISBN 978–0–8142–9142–9) Cover design by Melissa Ryan Text design by Juliet Williams Type set in Adobe Sabon Printed by Thomson-Shore, Inc. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials. ANSI Z39.48–1992. 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 CONTENTS Acknowledgments vii Introduction PHYLLIS STERNBERG PERRAKIS 1 Part I Doris Lessing: Spiraling the Waves of Detachment 1.