Kaupapa Rangahau: a Reader a Collection of Readings from the Kaupapa Rangahau Workshop Series

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Margie Abbott 1

NEWSLETTER OF THE AU STRALIAN & AOTEAROA Nov 2013 Edition 3 NEW ZEALAND PSYCHOD RAMA ASSOCIATION A Tribute to Max The very first tribute to Max was SOCIO sent in for the last edition of Socio by Colin Martin. I missed including Welcome to Edition Three... the tribute and today it receives pride of place on From the AANZPA Executive page one. Greetings to all - We continue to keep you all in mind as we follow through with the tasks we set ourselves at our last meeting in Melbourne. As we are preparing to meet again in January we look forward to renewed physical contact Max Clayton and a reprieve from emails and Skype meetings. I am revelling in the beautiful spring weather and the abundance of life in my garden which sustains me. As I write this I realise that I am warming up strongly to the I learned so much Melbourne Conference and looking forward to being with you there. from Max that affected deeply my Sara Crane work, my well-being and my life. On workshops Max often pushed In this Edition From the Editor me to where I did not wish to go, Message from Sara Crane and a 1 I am pleased to present the third and so I learned. I tribute to Max Clayton edition of Socio to you. love Max and Garden of Spontaneity 2 remember all the This edition features reminders Regional News: Qld 3 about the Melbourne AANZPA good times we had Regional News: WA; Canterbury; 4-8 Conference in January; news from together, on Octago; NSW/ACT; Victoria the regions and an article from AANZPASA 9 Anna Schaum whom some of you workshops, on met at the Wellington AANZPA travels, on holiday, AANZPA Northern Region 10-12 Conference. -

Manawa Whenua, Wē Moana Uriuri, Hōkikitanga Kawenga from the Heart of the Land, to the Depths of the Sea; Repositories of Knowledge Abound

TE TUMU SCHOOL OF MĀORI, PACIFIC & INDIGENOUS STUDIES Manawa whenua, wē moana uriuri, hōkikitanga kawenga From the heart of the land, to the depths of the sea; repositories of knowledge abound ___________________________________________________________________________ Te Papa Hou is a trusted digital repository providing for the long-term preservation and free access to leading scholarly works from staff and students at Te Tumu, School of Māori, Pacific and Indigenous Studies at the University of Otago, Dunedin, New Zealand. The information contained in each item is available for normal academic purposes, provided it is correctly and sufficiently referenced. Normal copyright provisions apply. For more information regarding Te Papa Hou please contact [email protected] ___________________________________________________________________________ Author: Professor Michael P.J Reilly Title: A Stranger to the Islands: voice, place and the self in Indigenous Studies Year: 2009 Item: Inaugural Professorial Lecture Venue: University of Otago, Dunedin, New Zealand http://eprintstetumu.otago.ac.nz Inaugural Professorial Lecture A Stranger to the Islands: voice, place and the self in Indigenous Studies Michael P.J. Reilly Tēnā koutou katoa, Kia orana kōtou katoatoa, Tangi kē, Welcome and Good Evening. This lecture presents the views of someone anthropologists call a participant-observer, and Māori characterise as a Pākehā, a manuhiri (guest, visitor), or a tangata kē (stranger); the latter two terms contrast with the permanence of the indigenous people, the tangata whenua (people of the land). All of us in this auditorium affiliate to one of these two categories, tangata kē and tangata whenua; sometimes to both. We are all inheritors of a particular history of British colonisation that unfolded within these lands from the 1800s (a legacy that Hone Tuwhare describes as ‘Victoriana-Missionary fog hiding legalized land-rape / and gentlemen thugs’).1 This legalized violation undermined the hospitality and respect assumed between tangata whenua and tangata kē. -

ON TRICKY GROUND Researching the Native in the Age of Uncertainty Linda Tuhiwai Smith

04-Denzin.qxd 2/7/2005 9:28 PM Page 85 4 ON TRICKY GROUND Researching the Native in the Age of Uncertainty Linda Tuhiwai Smith 2 INTRODUCTION epistemological approaches, and challenges to the way research is conducted. The neighbors are In the spaces between research methodologies, misbehaving as well. The pursuit of new scientific ethical principles, institutional regulations, and and technological knowledge, with biomedical human subjects as individuals and as socially research as a specific example, has presented new organized actors and communities is tricky challenges to our understandings of what is scien- ground. The ground is tricky because it is compli- tifically possible and ethically acceptable.The turn cated and changeable, and it is tricky also because back to the modernist and imperialist discourse of it can play tricks on research and researchers. discovery,“hunting, racing, and gathering” across Qualitative researchers generally learn to recognize the globe to map the human genome or curing and negotiate this ground in a number of ways, disease through the new science of genetic engi- such as through their graduate studies,their acqui- neering, has an impact on the work of qualitative sition of deep theoretical and methodological social science researchers. The discourse of understandings, apprenticeships, experiences and discovery speaks through globalization and the practices, conversations with colleagues, peer marketplace of knowledge. “Hunting, racing, and reviews, their teaching of others. The epistemo- gathering” is without doubt about winning. But logical challenges to research—to its paradigms, wait—there is more. Also lurking around the practices, and impacts—play a significant role in corners are countervailing conservative forces that making those spaces richly nuanced in terms of seek to disrupt any agenda of social justice that the diverse interests that occupy such spaces and may form on such tricky ground. -

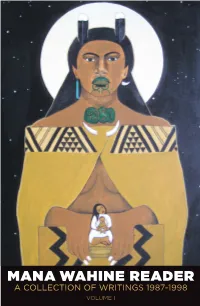

MANA WAHINE READER a COLLECTION of WRITINGS 1987-1998 2 VOLUME I Mana Wahine Reader a Collection of Writings 1987-1998 Volume I

MANA WAHINE READER A COLLECTION OF WRITINGS 1987-1998 2 VOLUME I Mana Wahine Reader A Collection of Writings 1987-1998 Volume I I First Published 2019 by Te Kotahi Research Institute Hamilton, Aotearoa/ New Zealand ISBN: 978-0-9941217-6-9 Education Research Monograph 3 © Te Kotahi Research Institute, 2019 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, without prior written permission of the publisher. Design Te Kotahi Research Institute Cover illustration by Robyn Kahukiwa Print Waikato Print – Gravitas Media The Mana Wahine Publication was supported by: Disclaimer: The editors and publisher gratefully acknowledge the permission granted to reproduce the material within this reader. Every attempt has been made to ensure that the information in this book is correct and that articles are as provided in their original publications. To check any details please refer to the original publication. II Mana Wahine Reader | A Collection of Writings 1987-1998, Volume I Mana Wahine Reader A Collection of Writings 1987-1998 Volume I Edited by: Leonie Pihama, Linda Tuhiwai Smith, Naomi Simmonds, Joeliee Seed-Pihama and Kirsten Gabel III Table of contents Poem Don’t Mess with the Māori Woman - Linda Tuhiwai Smith 01 Article 01 To Us the Dreamers are Important - Rangimarie Mihomiho Rose Pere 04 Article 02 He Aha Te Mea Nui? - Waerete Norman 13 Article 03 He Whiriwhiri Wahine: Framing Women’s Studies for Aotearoa Ngahuia Te Awekotuku 19 Article 04 Kia Mau, Kia Manawanui -

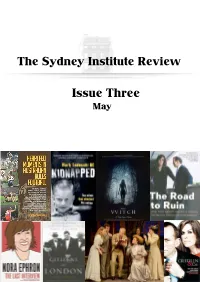

Issue Three May Contents

The Sydney Institute Review Issue Three May Contents Book Reviews CHURCHILL AND HIS LOYAL AMERICANS 3 Citizens of London – The Americans Who Stood with Britain in its Darkest, Finest Hour By Lynne Olson Reviewed by Anne Henderson THE FALL OF TONY ABBOTT AS JACOBEAN DRAMA 7 The Road to Ruin: How Tony Abbott and Peta Credlin destroyed their own government by Niki Savva Credlin and Co: How the Abbott government destroyed itself by Aaron Patrick Reviewed by Stephen Matchett NOT JUST A FUNNY LADY – REMEMBERING NORA EPHRON 14 Nora Ephron: The Last Interview and Other Conversations Reviewed by Anne Henderson MURDER MOST FOUL: IN MELBOURNE & SYDNEY 16 Certain Admissions: A Beach, A Body and a Lifetime of Secrets By Gideon Haigh Kidnapped: The Crime that Stopped the Nation By Mark Tedeschi QC Reviewed by Gerard Henderson THE BIG BOYS FLY UP 21 Heartfelt Moments in Australian Rules Football edited by Ross Fitzgerald Reviewed by Paul Henderson Film & Stage Reviews DYSTOPIAN LEAPS WITH ALGORITHMS 24 Golem, Sydney Theatre Company Reviewed by Nathan Lentern A WISTFUL SENSE OF WHAT MIGHT HAVE BEEN 26 The Importance of Being Earnest: A Trivial Comedy for Serious People Reviewed by Nathan Lentern THE WITCH: A NEW ENGLAND FOLKTALE 28 Directed by Robert Eggers Reviewed by Paige Hally CHURCHILL AND HIS LOYAL AMERICANS Citizens of London – The Americans Who Stood with Britain in its Darkest, Finest Hour By Lynne Olson Scribe Publications 2015 ISBN-10: 1400067588 ISBN-13: 978-1400067589 RRP - $27.99 pb Reviewed by Anne Henderson In the UK spring of 1941, the Luftwaffe rained down bombs on a number of the UK’s industrial cities and ports, trying to sever Britain’s supplies and damage production. -

Kaupapa Māori Research

Working What can Pākehā Paper learn from engaging in kaupapa Māori 01 educational research? What can Pākehā learn from engaging in kaupapa Māori educational research? Working Paper 1 Alex Barnes OCTOBER 2013 New Zealand Council for Educational Research PO Box 3237 Wellington New Zealand ISBN 978‐1‐927231‐05‐0 © Alex Barnes, 2013 He Whakamihi—Acknowledgements E ngā mate rarahi o te wā, haere atu rā koutou ki te huinga o te kahurangi, oti atu ai. Kia hoki mai ki a tātou, ki ngā kanohi ora, kei aku kuru pounamu, kei aku toka tū moana, tēnā koutou katoa. Kei ngā kākano i ruia mai i Rangiātea, mō koutou i manaaki mai i tēnei uri, nāu i pakari ai te tū a tēnei uri. E Ngāi Māori mā, e ngā Peka Tītoki, e kore e ea i te kupu ngā mihi o te ngākau. This working paper would not be possible without my varied experiences in te ao Māori. E aku iti, aku rahi, ka tika te whakataukī “E ea ai te werawera o Tāne tahuaroa, me heke te werawera o Tāne te wānanga.” I wish to acknowledge my connections to the various whānau, hapū, and iwi who have supported my family and me to enter into te ao Māori, become bilingual, and live in work in Pākehā and Māori worlds. Firstly, Tauranga Moana iwi (Ngāi Te Rangi, Ngāti Ranginui, Ngāti Pūkenga iwi and Ngā Pōtiki hapū) for inviting and supporting my Pākehā family involvement in kōhanga reo, kura kaupapa, and bilingual education. Secondly, Ngāti Raukawa ki te Tonga iwi, and Ngāti Pareraukawa hapū (Ōtaki, Hōkio Beach) where I continue to work on a host of social, cultural, and environmental issues. -

Landhow Conservative Politics Destroyed Australia's 44Th Parliament

NEGATIVE LANDHow conservative politics destroyed Australia’s 44th Parliament To order more copies of this great book: newpolitics.com.au/nl-order To purchase the e-book for Kindle: newpolitics.com.au/nl-kindle Like or don’t like the book? To post a review on Amazon: newpolitics.com.au/nl-amazon Negativeland: How conservative politics destroyed Australia’s 44th parliament ISBN: 978-0-9942154-0-6 ©2017 Eddy Jokovich @EddyJokovich Published by New Politics Coverhttp://www.seeklogo.net design: Madeleine Preston New Politics PO Box 1265, Darlinghurst NSW 1300 www.newpolitics.com.au Email: [email protected] National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Creator: Jokovich, Eddy, author. Title: Negative land : how conservative politics destroyed Australia’s 44th parliament / Eddy Jokovich. ISBN: 9780994215406 (paperback) Subjects: Essays. Conservatism--Australia. Conservatism in the press--Australia. Australia--Politics and government. Contents BEFORE THE STORM Election 2013: The final countdown ........................................................................5 PARLIAMENT 44 A government not in control of itself .................................................................... 10 Tony Abbott: Bad Prime Minister .............................................................................13 The ‘stop drownings at sea mantra’ cloaks a racist agenda ..................... 20 A very Australian conservative coup ....................................................................26 What is Tony Abbott hiding? .....................................................................................32 -

Vol 114 No 1124: 26 January 2001

THETHE NEWNEW ZEALANDZEALAND MEDICALMEDICAL JOURNALJOURNAL Vol 114 No 1124 Journal of the New Zealand Medical Association 26 January 2001 INFORMATION FOR AUTHORS NEWSLETTER First page following cover (pages 1-6) EDITORIALS 1 Making resuscitation decisions: balancing ethics with the facts Adam Dangoor, Chris Atkinson 1 Future directions in healthcare in New Zealand: my vision Wyatt Creech ORIGINAL ARTICLES 3 Necrotizing fasciitis and non steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: a case series and review of the literature Nadia Forbes, Alan Patrick Nigel Rankin 6 The Work-Related Fatal Injury Study: numbers, rates and trends of work-related fatal injuries in New Zealand 1985-1994 Anne-Marie Feyer, John Langley, Maureen Howard, Simon Horsburgh, Craig Wright, Jonathan Alsop, Colin Cryer 11 Delay in diagnosis of anterior cruciate ligament injury in sport Nigel I Hartnett, Russell JA Tregonning 13 Psychological problems in New Zealand primary health care: a report on the pilot phase of the Mental Health and General Practice Investigation (MaGPIe) The MaGPIe Research Group VIEWPOINT 16 Saying is believing Margie Comrie MEDICOLEGAL DIARY 18 Refusing emergency life-sustaining treatment Jonathan Coates ISSN 0028 8446 26 January 2001 New Zealand Medical Journal 1 Twice monthly except December & January THETHE NEWNEW ZEALANDZEALAND MEDICALMEDICAL JOURNALJOURNAL Established 1887 - Journal of the New Zealand Medical Association Twice monthly except December & January Copyright New Zealand Medical Association ISSN 0028 8446 Editor: Gary Nicholls Deputy Editors: -

To Download the Latest E-Edition of the Maritime Workers' Journal

THE MARITIME WORKERS’ JOURNAL AUTUMN/WINTER 2013 FIGHT FOR LIFE, SIGN FOR LIFE NSCOP CAMpaIGN ESCALATES THE FIGHT AGAINST AUTOMATION WITHOUT NEGOTIATION WORKCHOICES: WHATEVER THE NAME NEVER AGAIN. WHY We’re FIGHTING ABBOTT AT THE ELECTION contents 2 Logging On: A Message From National Secretary Paddy Crumlin 6 Fight for life: MUA’s First National Safety Conference 8 Automation: People Before Machines, Dignity Before Profits 14 Election: The Fight For The Future Is On 18 Conference: WA Branch Spotlights Global Solidarity 30 Women: You Don’t Get Me Tony EDITOR IN CHIEF Paddy Crumlin NEWS, FEATURES & PICTORIAL Jonathan Tasini DESIGN Magnesium Media PRINTER Printcraft Maritime Workers’ Journal 365-375 Sussex Street Sydney NSW 2000 Contact: 9267 - 9134 Fax: 9261 - 3481 Email: [email protected] Website: http://www.mua.org.au MWJ reserves the right at all times to edit and/or reduce any articles or letters to be published. Publication No: 1235 For all story ideas, letters, obituaries please email [email protected] ON THE COVER: NSCOP, MUA AUTOMATION CAMPAIGN AND THE FEDERAL ELECTIONS THIS PAGE (Left): DELEGATES To THE FIRST MUA NATIonaL SAFETY CONFERENCE IN BRISBANE logging on logging on Iron Lady-Rust in Peace a close friend and ally of Thatcher. It was face of an accelerated move around the world to LOGGING Margaret Thatcher did incalculable damage a Thatcher-Reagan assault on responsible higher technology. It was pretty instructive. to millions of human beings in the UK and the economic and social modeling, allowing the Automation and mechanisation are features ON world, leaving a path of community destruction gorging of wealth by banks, corporations and of our industry as it is for many other industries. -

Foundation Report 2015-2016

The Royal Hospital for Women Foundation Foundation Report 2015-2016 Create Life. Save Lives. Donate Now. Table of contents About The Foundation 5 Welcome About The Royal 5 Our Chairman 6 Our CEO 7 RHW General Manager 9 Our people Our Board 10-11 Our Ambassador 13 Annual Dinner 2015 14 Secret Men’s Business 15 Annual Dinner 2014 15 Events Objects of Desire 16 BAZAAR in Bloom 17 Community Fundraising 19 Kiosk and volunteers 20 Numbers at a glance 20 Community Celebrating 150 Years 21 Key Projects and impact 23 Key Projects and impact 25 Health Education 27 Key projects and impact Current partners 28 Milestones 29 Projects for funding 30 Hospital Wishlist 31 Financial statements 32-68 Financial statements 1866: Dr Arthur Renwick converted the Lying-in branch to the Lying-in hospital which was the leading obstetric facility in New South Wales The Royal Hospital for Women Foundation The Royal Hospital for Women Foundation exists to provide essential and significant financial assistance to cover the equipment, research and clinical services of the Hospital and the promotion of women’s health in the community. Our Vision is to provide women, their babies and their families with excellent care in a responsive, collaborative environment that promotes best practice teaching, research and staff. The Royal Hospital for Women The Royal Hospital for Women is the leading facility for the specialist care of women and newborns in NSW. It is the only public women’s hospital in the state with an outstanding reputation both nationally and internationally for health care excellence, teaching and research. -

Working Paper

Q&A Transcript – Working Paper This is my rough working paper, provided for anyone who wants to check my figures. Generally, I have counted ‘interruptions’ where a panellist is interrupted mid-sentence as indicated by elipses ( …) in the transcript. There are some additional incidents where, I believe, it is clear that an interruption has occurred – despite the absence of elipses. For example, where Jones specifically asks one panellist to speak and another butts in before they have a chance to respond. When someone has cut in on a conversation and either Jones or the original speaker cuts in, I have not counted that as an interruption (as indicated in parenthetic comments added to the text). Where one speaker obviously butts in to a conversation, but this occurs after the previous speaker has ended a sentence, I have marked this as an ‘interjection’ but, to be fair, I have not included these in the counts or the blog post. On the whole, I believe that the number of ‘interruptions’ I have attributed to Pyne et al is a conservative estimate. Q&A is based on discussions and, of course, interruptions are a normal part of discussions. I do not intend to perjorative in listing interruptions. Of course, not all of them are rude or unwelcome. However, when one panellist makes an extraordinarily high number of interruptions or another panellist is the recipient of an extraordinarily high number of interruptions it does seem to indicate something more than the cut and thrust of ordinary discussion. Word Count Jones: 1881 words (approx.) Pyne: -

SP9 Māori Custom and Values in New Zealand Law (PDF)

Study Paper 9 MÄORI CUSTOM AND VALUES IN NEW ZEALAND LAW March 2001 Wellington, New Zealand The Law Commission is an independent, publicly funded, central advisory body established by statute to undertake the systematic review, reform and development of the law of New Zealand. Its purpose is to help achieve law that is just, principled, and accessible, and that reflects the heritage and aspirations of the peoples of New Zealand. The Commissioners are: The Honourable Justice Baragwanath – President Judge Margaret Lee DF Dugdale Timothy Brewer ED Paul Heath QC The Executive Manager of the Law Commission is Bala Benjamin The office of the Law Commission is at 89 The Terrace, Wellington Postal address: PO Box 2590, Wellington 6001, New Zealand Document Exchange Number: SP 23534 Telephone: (04) 473–3453, Facsimile: (04) 471–0959 Email: [email protected] Internet: www.lawcom.govt.nz Use of submissions The Law Commission’s processes are essentially public, and it is subject to the Official Information Act 1982. Thus copies of submissions made to the Commission will normally be made available on request, and the Commission may mention submissions in its reports. Any request for the withholding of information on the grounds of confidentiality or for any other reason will be determined in accordance with the Official Information Act 1982. Study Paper/Law Commission, Wellington, 2001 ISSN 1174–9776 ISBN 1–877187–64–X This study paper may be cited as: NZLC SP9 This study paper is also available from the internet at the Commission’s website: www.lawcom.govt.nz ii MÄORI CUSTOM AND VALUES IN NEW ZEALAND LAW E KORE E NGARO HE KÄKANO I RUIA MAI I RANGIÄTEA I WILL NEVER BE LOST FOR I AM A SEED SOWN FROM RANGIÄTEA Rangiätea refers to the original homeland of Mäori before they came to Aotearoa.