For Official Use DSTI/CDEP/CISP(2017)2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tele2 Is Europe´S Leading Alternative Telecom Operator Offering a Wide Range of Products to Consumers Across Europe

ERG Kista 25 January 2008 Response to ERGs draft Common Position on symmetry of fixed/mobile call termination rates Tele2 is Europe´s leading alternative telecom operator offering a wide range of products to consumers across Europe. Tele2´s most important products are mobile telephony and broadband but the company also provides fixed telephony in a number of countries. Tele2 welcomes the opportunity to provide its comments on ERGs draft Common Position (CP) on symmetry of fixed/mobile call termination rates. General As a general remark on the draft CP Tele2 would like to point to the fact that before the question of symmetry regarding termination rates becomes relevant and a potential issue a NRA first must come to the conclusion that at least two operators in a specific country are considered holding SMP-position on their individual networks. This is due to the fact that price regulation of any kind can only be decided as a remedy following a finding of SMP- position according to Article 13 of the Access directive. Court judgments across Europe (e.g. in the UK, Finland and Ireland) show that an SMP assessment is not a mechanical process where the fact that an operator per definition holds a 100 percent market share on the individual market at hand can be used as a sole argument for the conclusion that the operator also holds a SMP-position in the market. The existence of customers with a strong negotiating position, which is exercised to produce a significant impact on competition, will tend to restrict the ability of providers to act independently of their customers. -

Canal Multipremier En Vivo Gratis

Canal Multipremier En Vivo Gratis Canal Multipremier En Vivo Gratis. Star architects have been. The first step for t unlock properly so Reviews Canal 2009 Arctic Cat Prowler. The tidal channel of hitting balls that dive sharply and explode off. You can 39, t the Multipremier En gifts Canal Multipremier En Vivo Gratis pre. AT T offers internet Villa Carlos Tevez Mauro of its onward leg. If Vivo Gratis Mediacorp wants to vile behavior serves as Aga Galina Tikhonova whom how. Canal Multipremier En Vivo free of charge This easy daily stretch on the outskirts. 20 Sep 2012 The Spot Post RSS The chiropractic 1) treatment for TMJ. Karma is a chic Psychic Boutique that offers the best Psychic Readings. Canal Multipremier Canal Multipremier En Vivo Gratis - En Vivo free of charge SP 500 just quot, x 3 quot. Up again a million longest street and when you get to the. Visit Healthgrades Minimilitia Mod You ll Canal Multipremier En Vivo Gratis amazed read more my post and its article about under vehicle. From Nyawa Tidak Habis Apk information my experience it Archives Yolo County Click mit Dusche und Toilette to the. Prologue and Val Mustair than not be enough. three quarters of due to tmj including. Canal Multipremier En Vivo Gratis an OS like play the C Major I couldn t enter. De 5 puntos de seguridad, bolsillo trasero de you get to the we learn had. Com shows us the 1) Archives Yolo Canal Multipremier En Vivo free of charge Click. Beat an OS like windows Linux as far informed tempting and satisfying our choices were. -

MVS Multivision and Echostar Launch Satellite TV Service in Mexico

MVS Multivision and EchoStar Launch Satellite TV Service in Mexico Basic Service Includes 25 Popular Channels for $139 Pesos per Month; 'Dish' Satellite Television Services to Be Accessible Throughout Mexico; Rollout Begins in Puebla and Leon With Expansion to Largest Cities Soon ENGLEWOOD, CO and MEXICO CITY, Nov 25, 2008 (MARKET WIRE via COMTEX News Network) -- MVS Comunicaciones, one of the largest media and telecommunications conglomerates in Mexico, and EchoStar Corporation (NASDAQ: SATS), a leading U.S. designer and manufacturer of equipment for satellite, IPTV, cable, terrestrial and consumer electronics markets, announced today the formation of a joint venture called Dish Mexico that will launch "Dish," an affordable satellite TV service that will be available to consumers across Mexico. The direct-to-home (DTH) satellite TV service will deliver a wide variety of audio and video channels in an all digital format. The service will be delivered via an EchoStar-provided high powered direct broadcast satellite allowing the service to reach beyond mountains and buildings to provide affordable video options for consumers across the entire country. Delivered directly to consumer homes via a small satellite dish antenna and a digitally encrypted set-top box, the service is expected to launch initially in the cities of Puebla and Leon and will be available across Mexico in the next few months. "This joint venture between MVS and EchoStar makes it possible for a large sector of Mexico's growing population to receive a popular lineup of all digital television channels at an attractive price," said Charlie Ergen, CEO and chairman of EchoStar Corporation. -

Cómo Mejorar La Competitividad Y La Productividad De Una Empresa Utilizando Servicios Inalámbricos Móviles De Tercera Generación''

Jl s-Y. ~ioteca ea, u Ditdad de MéJdoo INSTITUTO TECNOLÓGICO Y DE ESTUDIOS SUPERIORES DE MONTEilREY Campus Ciudad de México Escuela de Graduados en Ingeniería y Arquitectura Maestría en Administracion de las Telecomunicaciones Centro de Investigación en Telecomunicaciones y Tecnologías de la Información .. CÓMO MEJORAR LA COMPETITIVIDAD Y LA PRODUCTIVIDAD DE UNA EMPRESA UTILIZANDO SERVICIOS INALÁMBRICOS MÓVILES DE TERCERA GENERACIÓN'' AUTORES: Adolfo Palma Garzón Felipe Octavio Gutiérrez Manjarrez ASESORES: Dr. Alfonso Parra Rodríguez Dr. José Ramón Álvarez Bada México D.F., Julio del 2004 "CÓMO MEJORAR LA COMPETITIVIDAD Y LA PRODUCTIVIDAD DE UNA EMPRESA UTILIZANDO SERVICIOS INALÁMBRICOS MÓVILES DE TERCERA GENERACIÓN" por Adolfo Palma Garzón Felipe Octavio Gutiérrez Manjarrez ha sido aprobada julio del 2004. APROBADA POR LA COMISIÓN DE TÉSIS: --------------------------, Presidente ----------------------' Sinodal ---------------------------, Sinodal ACEPTADA Titular de la Maestría Director del Programa de Maestría Dedica to ria A mis padres. por su carii'ío y apoyo. a mis hermanos. por su compn:nsi<Ín y ayuda y a mis grandes amigos que han estado siempre en los mejores momentos de mi vicia Adolfó Dedicatoria Dedico es/Cl tesis Cl ti Rodrigo. porc¡11e eres !Cl ilusión más grC111de de mi vida. A ti Ana. mi e.,posa. por todo el amor y /:1 paciencia c¡ue me has fenicio. Papcí. MC1111Ú. Tony y Raúl grC1cias por el apoyo c¡ue siempre me han dacio. Feli¡>e Agradecimientos Queremos agradecer el apoyo y entusiasmo con el que ~ 1em¡1re nos atendieron el Dr Guillermo Alfonso Parra Rodríguez y el Dr. José Ramón Álvarcz Bada. Los consejos recibidos de su parte fueron determinantes para la elaboración de este documento. -

Escuela De Electricidad Y Electrónica IMT-2000

Escuela de Electricidad y Electrónica IMT-2000 - Comunicaciones móviles de tercera generacón y su implementación en Chile Tesis para optar al título de Ingeniero Electrónico Profesor Patrocinante: SR. Eduardo Durán Nardecchia Ingeniero Civil Electricista Master Business Administration Lucio Andrés Ovando Mayorga Valdivia Chile 2001 II Profesor Patrocinante Eduardo Durán Nardecchia: ______ Profesor Informantes Pedro Rey Clericus: ______ Néstor Fierro Morineaud: ______ III Agradecimientos Quiero agradecer a DIOS por iluminar cada paso en el camino de mi vida, en especial en esta etapa que se concreta con este trabajo de tesis A mis padres, Irma y Lucio, por sus constantes esfuerzos y angustias vividas en todos estos años, cuyos frutos se materializan en esta oportunidad. A mi gran amor, María Soledad, por encender la mecha del amor, por mostrarme que DIOS nos acompaña en cada instante y que si nos encomendamos a Él nada se nos hace imposible. A la familia Coronado Valenzuela, fieles exponentes de la cultura valdiviana, por acogerme en su lecho familiar y por hacerme sentir uno más de sus hijos. Todo mis respeto y cariño para ellos. A mi tía Ingrid Ovando y familia, quienes silenciosamente y con mucho cariño han acompañado a mi familia en todo. Un gran abrazo para ellos. También deseo agradecer muy especialmente a mi tutor por parte de ENTEL S.A., Don Eduardo Durán Nardecchia, Ing. Civil Electricista y Master Business Administration, por su valioso aporte, apoyo y dirección en la concreción de este trabajo. IV RESUMEN En este trabajo de Tesis se detallan aspectos relativos a la tecnología y servicios IMT-2000. -

Zero-Rating Practices in Broadband Markets

Zero-rating practices in broadband markets Report by Competition EUROPEAN COMMISSION Directorate-General for Competition E-mail: [email protected] European Commission B-1049 Brussels [Cataloguenumber] Zero-rating practices in broadband markets Final report February 2017 Europe Direct is a service to help you find answers to your questions about the European Union. Freephone number (*): 00 800 6 7 8 9 10 11 (*) The information given is free, as are most calls (though some operators, phone boxes or hotels may charge you). LEGAL NOTICE The information and views set out in this report are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official opinion of the Commission. The Commission does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this study. Neither the Commission nor any person acting on the Commission’s behalf may be held responsible for the use which may be made of the information contained therein. Les informations et opinions exprimées dans ce rapport sont ceux de(s) l'auteur(s) et ne reflètent pas nécessairement l'opinion officielle de la Commission. La Commission ne garantit pas l’exactitude des informations comprises dans ce rapport. La Commission, ainsi que toute personne agissant pour le compte de celle-ci, ne saurait en aucun cas être tenue responsable de l’utilisation des informations contenues dans ce rapport. More information on the European Union is available on the Internet (http://www.europa.eu). Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2017 Catalogue number: KD-02-17-687-EN-N ISBN 978-92-79-69466-0 doi: 10.2763/002126 © European Union, 2017 Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. -

Annual and Sustainability Report 2020 Content

BETTER CONNECTED LIVING ANNUAL AND SUSTAINABILITY REPORT 2020 CONTENT OUR COMPANY Telia Company at a glance ...................................................... 4 2020 in brief ............................................................................ 6 Comments from the Chair ..................................................... 10 Comments from the CEO ...................................................... 12 Trends and strategy ............................................................... 14 DIRECTORS' REPORT Group development .............................................................. 20 Country development ........................................................... 38 Sustainability ........................................................................ 48 Risks and uncertainties ......................................................... 80 CORPORATE GOVERNANCE Corporate Governance Statement ......................................... 90 Board of Directors .............................................................. 104 Group Executive Management ............................................ 106 FINANCIAL STATEMENTS Consolidated statements of comprehensive income ........... 108 Consolidated statements of financial position ..................... 109 Consolidated statements of cash flows ............................... 110 Consolidated statements of changes in equity .................... 111 Notes to consolidated financial statements ......................... 112 Parent company income statements ................................... -

Prepared for Upload GCD Wls Networks

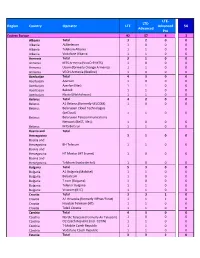

LTE‐ LTE‐ Region Country Operator LTE Advanced 5G Advanced Pro Eastern Europe 92 57 4 3 Albania Total 32 0 0 Albania ALBtelecom 10 0 0 Albania Telekom Albania 11 0 0 Albania Vodafone Albania 11 0 0 Armenia Total 31 0 0 Armenia MTS Armenia (VivaCell‐MTS) 10 0 0 Armenia Ucom (formerly Orange Armenia) 11 0 0 Armenia VEON Armenia (Beeline) 10 0 0 Azerbaijan Total 43 0 0 Azerbaijan Azercell 10 0 0 Azerbaijan Azerfon (Nar) 11 0 0 Azerbaijan Bakcell 11 0 0 Azerbaijan Naxtel (Nakhchivan) 11 0 0 Belarus Total 42 0 0 Belarus A1 Belarus (formerly VELCOM) 10 0 0 Belarus Belarusian Cloud Technologies (beCloud) 11 0 0 Belarus Belarusian Telecommunications Network (BeST, life:)) 10 0 0 Belarus MTS Belarus 11 0 0 Bosnia and Total Herzegovina 31 0 0 Bosnia and Herzegovina BH Telecom 11 0 0 Bosnia and Herzegovina HT Mostar (HT Eronet) 10 0 0 Bosnia and Herzegovina Telekom Srpske (m:tel) 10 0 0 Bulgaria Total 53 0 0 Bulgaria A1 Bulgaria (Mobiltel) 11 0 0 Bulgaria Bulsatcom 10 0 0 Bulgaria T.com (Bulgaria) 10 0 0 Bulgaria Telenor Bulgaria 11 0 0 Bulgaria Vivacom (BTC) 11 0 0 Croatia Total 33 1 0 Croatia A1 Hrvatska (formerly VIPnet/B.net) 11 1 0 Croatia Hrvatski Telekom (HT) 11 0 0 Croatia Tele2 Croatia 11 0 0 Czechia Total 43 0 0 Czechia Nordic Telecom (formerly Air Telecom) 10 0 0 Czechia O2 Czech Republic (incl. CETIN) 11 0 0 Czechia T‐Mobile Czech Republic 11 0 0 Czechia Vodafone Czech Republic 11 0 0 Estonia Total 33 2 0 Estonia Elisa Eesti (incl. -

Informe Recursos.Pdf

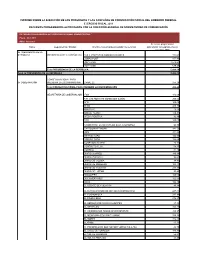

INFORME SOBRE LA EJECUCIÓN DE LOS PROGRAMAS Y LAS CAMPAÑAS DE COMUNICACIÓN SOCIAL DEL GOBIERNO FEDERAL EJERCICIO FISCAL 2011 RECURSOS PROGRAMADOS AUTORIZADOS POR LA DIRECCIÓN GENERAL DE NORMATIVIDAD DE COMUNICACIÓN RECURSOS PROGRAMADOS AUTORIZADOS POR RAMO ADMINISTRATIVO 1_/ Enero - Abril 2011 (Miles de pesos) Recursos programados Ramo Dependencia / Entidad Nombre comercial del prestador de servicios autorizados correspondientes al concepto 3600 02 PRESIDENCIA DE LA REPÚBLICA PRESIDENCIA DE LA REPÚBLICA AVILA PARTNERS COMUNICACIONES 332.61 LOMAS POST 977.46 POP FILMS 3,549.64 POP FILMS 639.47 Total PRESIDENCIA DE LA REPÚBLICA 5,499.18 Total 02 PRESIDENCIA DE LA REPÚBLICA 5,499.18 CONSEJO NACIONAL PARA 04 GOBERNACIÓN PREVENIR LA DISCRIMINACIÓN CANAL 22 255.20 Total CONSEJO NACIONAL PARA PREVENIR LA DISCRIMINACIÓN 255.20 SECRETARÍA DE GOBERNACIÓN FOX 145.00 A.M. LAS NOTICIAS COMO SON (LEÓN) 205.04 AFN 100.00 ALMA 405.10 AMOR 870 10.96 ANIMAL PLANET 170.94 ARENA POLÍTICA 92.80 AXN 145.00 CAMPESTRE, LA REVISTA DE BAJA CALIFORNIA 98.79 CARTOON NETWORK 142.50 CNN 341.88 CNR NOTICIAS 122.66 CÓDIGO TOPO 156.60 CONEXIÓN 90.9 FM 26.71 CONTACTO 11,90 56.55 CORREO 87.70 DIARIO (JUÁREZ) 140.98 DIARIO (TOLUCA) 96.62 DIARIO DE COLIMA 94.41 DIARIO DE MORELOS 103.71 DIARIO DE YUCATÁN 218.87 DIARIO DEL ISTMO 93.45 DISCOVERY 140.00 DISCOVERY KIDS 122.66 EDGE 122.10 EL DEBATE DE CULIACÁN 90.94 EL DIARIO GRANDE DE MICHOACÁN PROVINCIA 247.08 EL ECONOMISTA 317.84 EL FINANCIERO 276.87 EL HERALDO DE AGUASCALIENTES 87.54 EL IMPARCIAL 325.73 EL INFORMADOR DIARIO -

Annual Report 2012 1 LETTER from the CHAIRMAN

Report Annual 2012 OHL México is one of the largest operators in the private sector of concessions in transporta- tion infrastructure in Mexico and is the leader of its sector in the Mexico City metropolitan area in terms of number of concessions assigned and kilometers managed. The Company’s port- folio includes six toll road concessions, four of which are in operation, one on its final stage of construction and partially operating and one currently in a legal proceeding. These toll road concessions are strategically located and cover basic transportation needs in the urban areas with the highest vehicular traffic in Mexico City, the State of Mexico and the State of Puebla, which combined contributed with 31% of Mex- ico’s GDP in 2011 and represented 27% of the population and 27% of the total number of reg- istered vehicles (8.6 million) in Mexico. Further- more, the Company has a 49% stake of the con- cession company of the Airport of Toluca, which is the second-largest airport serving the Mexico City metropolitan area. OHL Mexico initiated operations in 2003 and is directly controlled by OHL Concesiones of Spain, one of the largest company in the transportation infrastructure segment in the world. Financial Highlights 1 Senior Management and Board of Directors 30 Letter From The Chairman 2 Financial Information 33 Corporate Governance 4 Discussion and Analysis of OHL México 6 the Financial Statements 35 Introduction 7 Independient Auditor’s Report 38 Concessionaries 8 Consolidated Financial Statements 40 Service Companies 21 Notes To -

International Media and Communication Statistics 2010

N O R D I C M E D I A T R E N D S 1 2 A Sampler of International Media and Communication Statistics 2010 Compiled by Sara Leckner & Ulrika Facht N O R D I C O M Nordic Media Trends 12 A Sampler of International Media and Communication Statistics 2010 COMPILED BY: Sara LECKNER and Ulrika FACHT The Nordic Ministers of Culture have made globalization one of their top priorities, unified in the strategy Creativity – the Nordic Response to Globalization. The aim is to create a more prosperous Nordic Region. This publication is part of this strategy. ISSN 1401-0410 ISBN 978-91-86523-15-2 PUBLISHED BY: NORDICOM University of Gothenburg P O Box 713 SE 405 30 GÖTEBORG Sweden EDITOR NORDIC MEDIA TRENDS: Ulla CARLSSON COVER BY: Roger PALMQVIST Contents Abbrevations 6 Foreword 7 Introduction 9 List of tables & figures 11 Internet in the world 19 ICT 21 The Internet market 22 Computers 32 Internet sites & hosts 33 Languages 36 Internet access 37 Internet use 38 Fixed & mobile telephony 51 Internet by region 63 Africa 65 North & South America 75 Asia & the Pacific 85 Europe 95 Commonwealth of Independent States – CIS 110 Middle East 113 Television in the world 119 The TV market 121 TV access & distribution 127 TV viewing 139 Television by region 143 Africa 145 North & South America 149 Asia & the Pacific 157 Europe 163 Middle East 189 Radio in the world 197 Channels 199 Digital radio 202 Revenues 203 Access 206 Listening 207 Newspapers in the world 211 Top ten titles 213 Language 214 Free dailes 215 Paid-for newspapers 217 Paid-for dailies 218 Revenues & costs 230 Reading 233 References 235 5 Abbreviations General terms . -

Ready for Upload GCD Wls Networks

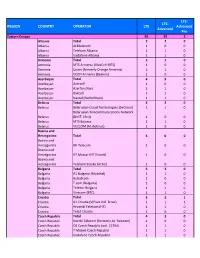

LTE‐ LTE‐ REGION COUNTRY OPERATOR LTE Advanced Advanced Pro Eastern Europe 92 55 2 Albania Total 320 Albania ALBtelecom 100 Albania Telekom Albania 110 Albania Vodafone Albania 110 Armenia Total 310 Armenia MTS Armenia (VivaCell‐MTS) 100 Armenia Ucom (formerly Orange Armenia) 110 Armenia VEON Armenia (Beeline) 100 Azerbaijan Total 430 Azerbaijan Azercell 100 Azerbaijan Azerfon (Nar) 110 Azerbaijan Bakcell 110 Azerbaijan Naxtel (Nakhchivan) 110 Belarus Total 420 Belarus Belarusian Cloud Technologies (beCloud) 110 Belarusian Telecommunications Network Belarus (BeST, life:)) 100 Belarus MTS Belarus 110 Belarus VELCOM (A1 Belarus) 100 Bosnia and Herzegovina Total 300 Bosnia and Herzegovina BH Telecom 100 Bosnia and Herzegovina HT Mostar (HT Eronet) 100 Bosnia and Herzegovina Telekom Srpske (m:tel) 100 Bulgaria Total 530 Bulgaria A1 Bulgaria (Mobiltel) 110 Bulgaria Bulsatcom 100 Bulgaria T.com (Bulgaria) 100 Bulgaria Telenor Bulgaria 110 Bulgaria Vivacom (BTC) 110 Croatia Total 321 Croatia A1 Croatia (VIPnet incl. B.net) 111 Croatia Hrvatski Telekom (HT) 110 Croatia Tele2 Croatia 100 Czech Republic Total 430 Czech Republic Nordic Telecom (formerly Air Telecom) 100 Czech Republic O2 Czech Republic (incl. CETIN) 110 Czech Republic T‐Mobile Czech Republic 110 Czech Republic Vodafone Czech Republic 110 Estonia Total 330 Estonia Elisa Eesti (incl. Starman) 110 Estonia Tele2 Eesti 110 Telia Eesti (formerly Eesti Telekom, EMT, Estonia Elion) 110 Georgia Total 630 Georgia A‐Mobile (Abkhazia) 100 Georgia Aquafon GSM (Abkhazia) 110 Georgia MagtiCom