The Age of Reform and Swami Vivekananda: an Alternative Approach

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dr. Manoj Kumar Assistant Professor

Dr. Manoj Kumar Assistant Professor ( Department of Political Science ) G.D. College, Begusarai ( L.N.M.U. Darbhanga) M.N. – 9532258109 Email- [email protected] Socio-Political Thoughts of Swami Vivekananda The ideas of Vivekananda cover almost all aspects of socio-political developments. We can make a list on which Vivekananda had given his remarks time and again: – i. Upholding nationalism ii. Implementation of Vedantic system of education. iii. Achieving social justice and a system of equal opportunity. iv. Steps towards socialism particularly achieving the concept of spiritual socialism. v. Development of marginalised classes (Dalits & untouchables) by adopting reasonable classification. vii. Steps towards secularism. All these ideas are similar to those enshrined in the preamble & fundamental rights chapter. The makers of Indian Constitution were much influenced by speeches and writings of Vivekananda. Therefore they incorporated the philosophies of Vivekananda while drafting Indian Constitution. The Constituent Assembly Members had repeatedly mentioned Vivekananda while debating on new provisions of Constitution, particularly in support of the philosophy behind the preamble and fundamental rights. The 19th century witnessed the dawn of renaissance in Bengal. Luminaries like Rammohan Roy, Debendranath Tagore, Iswar Chandra vidhyasagar introduced new ideas of social reforms. They started open protest against the social vices of the contemporary society. Rammohan Roy, who was considered as the ‗prophet of new India‘5 introduced the spirit of liberty, equality and fraternity in his religious and social reforms6 argued for modernisation of education, abolishment of social evils like sati, child marriage etc. Vidhyasagar, on the other hand, strongly agitated for adoption of a system of widow marriage in contemporary Bengali society. -

—No Bleed Here— Swami Vivekananda and Asian Consciousness 23

Swami Vivekananda and Asian Consciousness Niraj Kumar wami Vivekananda should be credited of transformation into a great power. On the with inspiring intellectuals to work for other hand, Asia emerged as the land of Bud Sand promote Asian integration. He dir dha. Edwin Arnold, who was then the principal ectly and indirectly influenced most of the early of Deccan College, Pune, wrote a biographical proponents of panAsianism. Okakura, Tagore, work on Buddha in verse titled Light of Asia in Sri Aurobindo, and Benoy Sarkar owe much to 1879. Buddha stirred Western imagination. The Swamiji for their panAsian views. book attracted Western intellectuals towards Swamiji’s marvellous and enthralling speech Buddhism. German philosophers like Arthur at the World Parliament of Religions in Chicago Schopenhauer and Friedrich Nietzsche saw Bud on 11 September 1893 and his subsequent popu dhism as the world religion. larity in the West and India moulded him into a Swamiji also fulfilled the expectations of spokesman for Asiatic civilization. Transcendentalists across the West. He did not Huston Smith, the renowned author of The limit himself merely to Hinduism; he spoke World’s Religions, which sold over two million about Buddhism at length during his Chicago copies, views Swamiji as the representative of the addresses. He devoted a complete speech to East. He states: ‘Buddhism, the Fulfilment of Hinduism’ on 26 Spiritually speaking, Vivekananda’s words and September 1893 and stated: ‘I repeat, Shakya presence at the 1893 World Parliament of Re Muni came not to destroy, but he was the fulfil ligions brought Asia to the West decisively. -

Communism and Religion in North India, 1920–47

"To the Masses." Communism and Religion in North India, 1920–47 Dissertation zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades doctor philosophiae (Dr. phil.) eingereicht an der Kultur-, Sozial- und Bildungswissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin von Patrick Hesse Präsident der Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin Prof. Dr. Jan-Hendrik Olbertz Dekanin der Kultur-, Sozial- und Bildungswissenschaftlichen Fakultät Prof. Dr. Julia von Blumenthal Gutachter: 1. Michael Mann 2. Dietrich Reetz Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: 20. Juli 2015 Abstract Among the eldest of its kind in Asia, the Communist Party of India (CPI) pioneered the spread of Marxist politics beyond the European arena. Influenced by both Soviet revolutionary practice and radical nationalism in British India, it operated under conditions not provided for in Marxist theory—foremost the prominence of religion and community in social and political life. The thesis analyzes, first, the theoretical and organizational ‘overhead’ of the CPI in terms of the position of religion in a party communist hierarchy of emancipation. It will therefore question the works of Marx, Engels, and Lenin on the one hand, and Comintern doctrines on the other. Secondly, it scrutinizes the approaches and strategies of the CPI and individual members, often biographically biased, to come to grips with the subcontinental environment under the primacy of mass politics. Thirdly, I discuss communist vistas on revolution on concrete instances including (but not limited to) the Gandhian non-cooperation movement, the Moplah rebellion, the subcontinental proletariat, the problem of communalism, and assertion of minority identities. I argue that the CPI established a pattern of vacillation between qualified rejection and conditional appropriation of religion that loosely constituted two diverging revolutionary paradigms characterizing communist practice from the Soviet outset: Western and Eastern. -

The Indian Revolutionaries and the Bolsheviks - Their Early Contacts, 1918-1922*

THE INDIAN REVOLUTIONARIES AND THE BOLSHEVIKS - THEIR EARLY CONTACTS, 1918-1922* JBy ARuN CooMER BosE INDIAN REVOLUTIONAJRIES USUALLY WORKED ON THE ASSUMPTION "ENG· land's difficulty is Indi;a's opportunity,"1 from which it followed that England's enemies are India's friends. So, Germany was their natural friend and patron du.. ing World War I. An Indian Independence Committee was formed there to act as a liaison between the German Government and the I ndian revolutionaries in di:ffierent · parts of the world, and the former spent over ten million marks to organise a revolt in India. By the end of 1916; however, their efforts had failed, and it was clear that nothing more could be done with German help. Naturally, some among the Indian revolutionaries began looking around for other possible sources of assistance. After .the March Revolution in Russia, Mahendra Pratap, President of the Provisional Government of Free India at Kabul, sent an emis- sary to Russian Turkis;tan, in the hope of some favourable response. But, he was told that the Kerensky Government would pursue the Czarist foreign ·policy of alliance with their western allies. However, the situation changed when the Bolsheviks came to power. They were reported to have invited Mahendra Pratap to visit Russia, and he went to Moscow in March 1918, on his way to Berlin. He had an inter· view even with Trots;ky. But, the Bolsheviks themselves were then engaged in a bitter struggle for survival, and were in no position to spare any assistance for the India revolutionaries. Mahendra Pratap went to Germany after a s.hort stay in Moscow,11 obviously not impressed with the Bolsheviks a.s possible friends of any particular value. -

Journal of Literature, Linguistics and Cultural Studies

RAINBOW Vol. 9 (2) 2020 Journal of Literature, Linguistics and Cultural Studies https://journal.unnes.ac.id/sju/index.php/rainbow Pre-partition India and the Rise of Indian Nationalism in Amitav Ghosh’s The Shadow Lines: A Postcolonial Analysis Sheikh Zobaer* * Lecturer, Department of English and Modern Languages, North South University, Dhaka, Bangladesh. Article Info Abstract Article History: The Shadow Lines is mostly celebrated for capturing the agony and trauma of the artificial Received segregation that divided the Indian subcontinent in 1947. However, the novel also 17 August 2020 provides a great insight into the undivided Indian subcontinent during the British colonial Approved period. Moreover, the novel aptly captures the rise of Indian nationalism and the struggle 13 October 2020 against the British colonial rule through the revolutionary movements. Such image of pre- Published partition India is extremely important because the picture of an undivided India is what 30 October 2020 we need in order to compare the scenario of pre-partition India with that of a postcolonial India divided into two countries, and later into three with the independence of Keywords: Partition, Bangladesh in 1971. This paper explores how The Shadow Lines captures colonial India Nationalism, and the rise of Indian nationalism through the lens of postcolonialism.s. Colonialism, Amitav Ghosh © 2020 Universitas Negeri Semarang Corresponding author: Bashundhara, Dhaka-1229, Bangladesh E-mail: [email protected] but cannot separate the people who share the INTRODUCTION same history and legacy of sharing the same territory and living the same kind of life for The Shadow Lines is arguably the most centuries. -

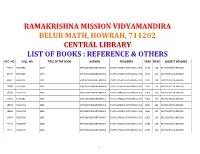

Ramakrishna Mission Vidyamandira Belur Math, Howrah, 711202 Central Library List of Books : Reference & Others Acc

RAMAKRISHNA MISSION VIDYAMANDIRA BELUR MATH, HOWRAH, 711202 CENTRAL LIBRARY LIST OF BOOKS : REFERENCE & OTHERS ACC. NO. CALL. NO. TITLE OF THE BOOK AUTHOR PUBLISHER YEAR PRICE SUBJECT HEADING 44638 R032/ENC 1978 ENYCOLPAEDIA BRITANNICA ENCYCLOPAEDIA BRITANNICA, ING 1978 150 ENCYCLOPEDIA-ENGLISH 44639 R032/ENC 1979 ENYCOLPAEDIA BRITANNICA ENCYCLOPAEDIA BRITANNICA, ING 1979 100 ENCYCLOPEDIA-ENGLISH 44641 R-032/BRI 1981 ENYCOLPAEDIA BRITANNICA ENCYCLOPEADIA BRITANNICA, INC 1981 100 ENCYCLOPEDIA-ENGLISH 15648 R-032/BRI 1982 ENYCOLPAEDIA BRITANNICA ENCYCLOPAEDIA BRITANNICA, ING 1982 100 ENCYCLOPEDIA-ENGLISH 15649 R-032/ENC 1983 ENYCOLPAEDIA BRITANNICA ENCYCLOPAEDIA BRITANNICA, ING 1983 100 ENCYCLOPEDIA-ENGLISH 17913 R032/ENC 1984 ENYCOLPAEDIA BRITANNICA ENCYCLOPAEDIA BRITANNICA, ING 1984 350 ENCYCLOPEDIA-ENGLISH 18648 R-032/ENC 1985 ENYCOLPAEDIA BRITANNICA ENCYCLOPAEDIA BRITANNICA, ING 1985 100 ENCYCLOPEDIA-ENGLISH 18786 R-032/ENC 1986 ENYCOLPAEDIA BRITANNICA ENCYCLOPAEDIA BRITANNICA, ING 1986 100 ENCYCLOPEDIA-ENGLISH 19693 R-032/ENC 1987 ENYCOLPAEDIA BRITANNICA ENCYCLOPEADIA BRITANNICA, INC 1987 100 ENCYCLOPEDIA-ENGLISH 21140 R-032/ENC 1988 ENYCOLPAEDIA BRITANNICA ENCYCLOPEADIA BRITANNICA, INC 1988 100 ENCYCLOPEDIA-ENGLISH 21141 R-032/ENC 1989 ENYCOLPAEDIA BRITANNICA ENCYCLOPEADIA BRITANNICA, INC 1989 100 ENCYCLOPEDIA-ENGLISH 1 ACC. NO. CALL. NO. TITLE OF THE BOOK AUTHOR PUBLISHER YEAR PRICE SUBJECT HEADING 21426 R-032/ENC 1990 ENYCOLPAEDIA BRITANNICA ENCYCLOPAEDIA BRITANNICA, ING 1990 150 ENCYCLOPEDIA-ENGLISH 21797 R-032/ENC 1991 ENYCOLPAEDIA -

Swami Vivekananda's Devotion to His Mother Bhuvaneshwari Devi

Swami Vivekananda’s Devotion to His Mother Bhuvaneshwari Devi By Swami Tathagatananda The study of the cultural history of the world gives us an insight about the deep impact of religion on human development. Religious ideals, unflinching faith in divinity and a spiritual orientation permeate daily life. To understand a culture, we must evaluate the harmonious religious values of that culture. The English historian Christopher Dawson expressed this view: . throughout the greater part of mankind’s history, in all ages and states of society, religion has been the great unifying force in our culture. It has been the guardian of tradition, the preserver of the moral law, the educator and the teacher of wisdom. In all ages, the first creative works of a culture are due to a religious inspiration and dedicated to a religious end. The spiritual and ethical culture of any race preserves its noble characteristics. Swamiji says, “It is a change of the soul itself for the better that alone will cure the evils of life.” In his lecture, “The Future of India, Swamiji highlights the true role of culture: It is culture that withstands shocks, not a simple mass of knowledge. You can put a mass of knowledge into the world, but that will not do it much good. There must come culture into the blood. We all know in modern times of nations which have masses of knowledge, but what of them? They are like tigers, they are like savages, because culture is not there. Knowledge is only skin-deep, as civilization is, and a little scratch brings out the old savage. -

Colonialism & Cultural Identity: the Making of A

COLONIALISM & CULTURAL IDENTITY: THE MAKING OF A HINDU DISCOURSE, BENGAL 1867-1905. by Indira Chowdhury Sengupta Thesis submitted to. the Faculty of Arts of the University of London, for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Oriental and African Studies, London Department of History 1993 ProQuest Number: 10673058 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10673058 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 ABSTRACT This thesis studies the construction of a Hindu cultural identity in the late nineteenth and the early twentieth centuries in Bengal. The aim is to examine how this identity was formed by rationalising and valorising an available repertoire of images and myths in the face of official and missionary denigration of Hindu tradition. This phenomenon is investigated in terms of a discourse (or a conglomeration of discursive forms) produced by a middle-class operating within the constraints of colonialism. The thesis begins with the Hindu Mela founded in 1867 and the way in which this organisation illustrated the attempt of the Western educated middle-class at self- assertion. -

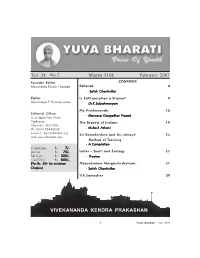

Feb 2007.Pdf

Vol. 34 No.7 Magha 5108 February 2007 Founder Editor CONTENTS Mananeeya Eknathji Ranade Editorial 4 - Satish Chowkulkar Editor Is Saffronisation a Stigma? 9 Mananeeya P. Parameswaran - Dr.K.Subrahmanyam My Vivekananda 15 Editorial Office - Mannava Gangadhar Prasad 5, Singarachari Street Triplicane, The Bravest of Indians 19 Chennai - 600 005 Ph: (044) 28440042 - Mukesh Advani email:[email protected] Sri Ramakrishna and His Unique 23 web: www.vkendra.org Method of Training - A Compilation SingleCopy Rs. 7/- Annual Rs. 75/- Letter - Youth and Ecology 27 For 3 yrs Rs. 200/- - Preetee Life(20Yrs) Rs. 800/- (Plus Rs. 30/- for outstation Maasaanaam Margashirshoham.. 31 Cheques) - Satish Chowkulkar V.K.Samachar 39 VIVEKANANDA KENDRA PRAKASHAN VIVEKANANDA KENDRA3 PRAKASHANYUVA BHARATI - Feb 2007 yae devana< àÉvíaeщví ivñaixpae éÔae mhi;R> , ihr{ygÉeR jnyamas pUveR s nae buXya zuÉya s<yun´… .41. May He, the creator and supporter of the gods, the lord of all, the destroyer of evil, the great seer, He who brought the cosmic Soul into being, endow us with good thoughts. --Svetasvataropanishad, III,4. Editorial Dynamics of Sankalpa d) What I must do to strengthen my capacities to meet these challenges. Almost everyone of us, at some time or other, take a Sankalpa or make a resolution So, before venturing for any Karya, in our – vow, to do something. Quite a few of these tradition, we make a Sankalpa. In this resolutions are not fulfilled. It is a practice to Sankalpa Mantrana, we remind ourselves as make resolution or take a Sankalpa for doing to in what time span we are i.e. -

Communist Movement in India Study Material

Communist Movement in India Study Material COMMUNIST MOVEMENT IN INDIA socialist revolution as it was populated by an industrial working class. On the other hand, the Berlin group of Manabendra Nath Roy, earlier known as Narcndra the Indian revolutionaries represented by Virendranath Nath Bhattachuryu. is credited to be the founder of the Chattopadhyay, Maulana Barkatullah and communist movement in India. He attended the Bhupendranath Datta had a positive aspect of Second Congress of Communist International in nationalism and considered India as an ugrarian Russia and in Tashkent along with Evelina Trench country. Roy, Abani Mukhcrji, Rosa Fitingof, Mohammad Ali (Ahmed Hasan), Mohammad Shafiq Siddiqui; he SIXTH CONGRESS OF THE founded the emigre Communist Party of India on 17 COMMUNIST INTERNATIONAL October 1920. He had earlier played an important role in the forminging of the Communist Party of Mexico The sixth congress of the Communist in 1919. Roy kept in contact with the Anushilan and International met in 1928. The colonial thesis of the Yuguntar groups in Bengal and tried to strengthen the 6th Comintern Congress demanded the Indian movement in India. Small communist groups were communists to protest against the national-reformist formed in Bengal (Jed by Muzaffar Ahmed), Mumbai leaders thus opposing Swarajists, Gandhists and their (led by S. A. Dange), Chennai (led by Singaravelu expression of passive resistance. The Tenth Plenum of Chettiar), United Provinces (led by Shaukat Usmani) the Executive Committee of the Communist and Punjab (led by Ghulam Hussain). The activities of International. 3-19 July 1929 directed Indian the new breed of revolutionaries caused panic among Communists to sever tics with WPP to which they the British administrators and on 17 March 1924, M. -

Sister Nivedita: Offering of Grace Prema Nandakumar

Sister Nivedita: Offering of Grace Prema Nandakumar could simply begin thus: I am writ- young Irish lady dedicated herself totally at the Iing now because of Sister Nivedita. I would feet of her guru to serve India. The guru was be literally and metaphorically correct. It Swami Vivekananda. is true that Indian women have entered the When Swamiji was going around India to get worlds of knowledge in a big way because a a first-hand idea of the needs of his motherland, he realised that two areas cried out for immedi- Prema Nandakumar is a literary critic, translator, ate action: the world of dalits and the world of author, and researcher from Srirangam, Tamil Nadu. women. Action needed the backing of money. PB January 2017 83 94 Prabuddha Bharata He resolved now to go to the United States to and Swamiji’s invitation gave her exactly that. earn funds for his work. After his speech at the Would she help bring education to India’s mar- Chicago Convention in 1893, he glowed like ginalised masses which included Indian women a flame atop a hill in the western world. On as well?: ‘I have been making plans for educating his way back to India, he tarried in London to the women of my country. I think you could be give a few speeches in 1895. He may not have of great help to me.’1 got the expected funds in England but he re- There followed a couple of years of corres- ceived the priceless gift of a peerless disciple, pondence, Swamiji patiently answered her ques- Sister Nivedita. -

Title & Imprint

MOTHER INDIA MONTHLY REVIEW OF CULTURE MARCH 2014 PRICE: Rs. 30.00 SUBSCRIPTIONS INLAND Annual: Rs. 200.00 For 10 years: Rs. 1,800.00 Price per Single Copy: Rs. 30.00 OVERSEAS Sea Mail: Annual: $35 or Rs. 1,400.00 For 10 years: $350 or Rs. 14,000.00 Air Mail: Annual: $70 or Rs. 2,800.00 For 10 years: $700 or Rs. 28,000.00 All payments to be made in favour of Mother India, Sri Aurobindo Ashram, Pondicherry. For outstation cheques kindly add Rs. 15 for annual membership and Rs. 50 for 10-year subscription. Subscribers are requested to mention their subscription number in case of any enquiry. The correspondents should give their full address in BLOCK letters, with pin code. Lord, Thou hast willed, and I execute, A new light breaks upon the earth, A new world is born. The things that were promised are fulfilled. All Rights Reserved. No matter appearing in this journal or part thereof may be reproduced or translated without written permission from the publishers except for short extracts as quotations. The views expressed by the authors are not necessarily those of the journal. All correspondence to be addressed to: MOTHER INDIA, Sri Aurobindo Ashram, Pondicherry - 605 002, India Phone: (0413) 2233642 e-mail: [email protected] Publishers: Sri Aurobindo Ashram Trust Founding Editor: K. D. SETHNA (AMAL KIRAN) Editors: RAVI, HEMANT KAPOOR, RANGANATH RAGHAVAN Published by: MANOJ DAS GUPTA SRI AUROBINDO ASHRAM TRUST PUBLICATION DEPARTMENT, PONDICHERRY 605 002 Printed by: SWADHIN CHATTERJEE at Sri Aurobindo Ashram Press, Pondicherry 605 002 PRINTED IN INDIA Registered with the Registrar of Newspapers under No.