In\C, \A T 3 T CL Ar2 Ia—V \(J(O 0 Pcu-Ouim Proquest Number: 10731345

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Metro Railway Kolkata Presentation for Advisory Board of Metro Railways on 29.6.2012

METRO RAILWAY KOLKATA PRESENTATION FOR ADVISORY BOARD OF METRO RAILWAYS ON 29.6.2012 J.K. Verma Chief Engineer 8/1/2012 1 Initial Survey for MTP by French Metro in 1949. Dum Dum – Tollygunge RTS project sanctioned in June, 1972. Foundation stone laid by Smt. Indira Gandhi, the then Prime Minister of India on December 29, 1972. First train rolled out from Esplanade to Bhawanipur (4 km) on 24th October, 1984. Total corridor under operation: 25.1 km Total extension projects under execution: 89 km. June 29, 2012 2 June 29, 2012 3 SEORAPFULI BARRACKPUR 12.5KM SHRIRAMPUR Metro Projects In Kolkata BARRACKPUR TITAGARH TITAGARH 10.0KM BARASAT KHARDAH (UP 17.88Km) KHARDAH 8.0KM (DN 18.13Km) RISHRA NOAPARA- BARASAT VIA HRIDAYPUR PANIHATI AIRPORT (UP 15.80Km) (DN 16.05Km)BARASAT 6.0KM SODEPUR PROP. NOAPARA- BARASAT KONNAGAR METROMADHYAMGRAM EXTN. AGARPARA (UP 13.35Km) GOBRA 4.5KM (DN 13.60Km) NEW BARRACKPUR HIND MOTOR AGARPARA KAMARHATI BISARPARA NEW BARRACKPUR (UP 10.75Km) 2.5KM (DN 11.00Km) DANKUNI UTTARPARA BARANAGAR BIRATI (UP 7.75Km) PROP.BARANAGAR-BARRACKPORE (DN 8.00Km) BELGHARIA BARRACKPORE/ BELA NAGAR BIRATI DAKSHINESWAR (2.0Km EX.BARANAGAR) BALLY BARANAGAR (0.0Km)(5.2Km EX.DUM DUM) SHANTI NAGAR BIMAN BANDAR 4.55KM (UP 6.15Km) BALLY GHAT RAMKRISHNA PALLI (DN 6.4Km) RAJCHANDRAPUR DAKSHINESWAR 2.5KM DAKSHINESWAR BARANAGAR RD. NOAPARA DAKSHINESWAR - DURGA NAGAR AIRPORT BALLY HALT NOAPARA (0.0Km) (2.09Km EX.DMI) HALDIRAM BARANAGAR BELUR JESSOR RD DUM DUM 5.0KM DUM DUM CANT. CANT 2.60KM NEW TOWN DUM DUM LILUAH KAVI SUBHAS- DUMDUM DUM DUM ROAD CONVENTION CENTER DUM DUM DUM DUM - BELGACHIA KOLKATA DASNAGAR TIKIAPARA AIRPORT BARANAGAR HOWRAH SHYAM BAZAR RAJARHAT RAMRAJATALA SHOBHABAZAR Maidan BIDHAN NAGAR RD. -

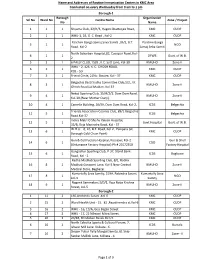

Name and Addresses of Routine Immunization Centers in KMC Area

Name and Addresses of Routine Immunization Centers in KMC Area Conducted on every Wednesday from 9 am to 1 pm Borough-1 Borough Organization Srl No Ward No Centre Name Zone / Project No Name 1 1 1 Shyama Club, 22/H/3, Hagen Chatterjee Road, KMC CUDP 2 1 1 WHU-1, 1B, G. C. Road , Kol-2 KMC CUDP Paschim Banga Samaj Seva Samiti ,35/2, B.T. Paschim Banga 3 1 1 NGO Road, Kol-2 Samaj Seba Samiti North Subarban Hospital,82, Cossipur Road, Kol- 4 1 1 DFWB Govt. of W.B. 2 5 2 1 6 PALLY CLUB, 15/B , K.C. Sett Lane, Kol-30 KMUHO Zone-II WHU - 2, 126, K. C. GHOSH ROAD, 6 2 1 KMC CUDP KOL - 50 7 3 1 Friend Circle, 21No. Bustee, Kol - 37 KMC CUDP Belgachia Basti Sudha Committee Club,1/2, J.K. 8 3 1 KMUHO Zone-II Ghosh Road,Lal Maidan, Kol-37 Netaji Sporting Club, 15/H/2/1, Dum Dum Road, 9 4 1 KMUHO Zone-II Kol-30,(Near Mother Diary). 10 4 1 Camelia Building, 26/59, Dum Dum Road, Kol-2, ICDS Belgachia Friends Association Cosmos Club, 89/1 Belgachia 11 5 1 ICDS Belgachia Road.Kol-37 Indira Matri O Shishu Kalyan Hospital, 12 5 1 Govt.Hospital Govt. of W.B. 35/B, Raja Manindra Road, Kol - 37 W.H.U. - 6, 10, B.T. Road, Kol-2 , Paikpara (at 13 6 1 KMC CUDP Borough Cold Chain Point) Gun & Cell Factory Hospital, Kossipur, Kol-2 Gun & Shell 14 6 1 CGO (Ordanance Factory Hospital) Ph # 25572350 Factory Hospital Gangadhar Sporting Club, P-37, Stand Bank 15 6 1 ICDS Bagbazar Road, Kol - 2 Radha Madhab Sporting Club, 8/1, Radha 16 8 1 Madhab Goswami Lane, Kol-3.Near Central KMUHO Zone-II Medical Store, Bagbazar Kumartully Seva Samity, 519A, Rabindra Sarani, Kumartully Seva 17 8 1 NGO kol-3 Samity Nagarik Sammelani,3/D/1, Raja Naba Krishna 18 9 1 KMUHO Zone-II Street, kol-5 Borough-2 1 11 2 160,Arobindu Sarani ,Kol-6 KMC CUDP 2 15 2 Ward Health Unit - 15. -

Abducted Women 70–73, 87–89, 94, 105 Agamben, Giorgio 221, 246 Agomoni 148 Agunpakhi 223, 225 Agrarian Movements 16, 75–76

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-06170-5 - The Partition of Bengal: Fragile Borders and New Identities Debjani Sengupta Index More information Index Abducted women 70–73, 87–89, 94, 105 Assam 2–3, 122, 150, 160, 180, 182, 185, Agamben, Giorgio 221, 246 188–93, 196–97, 214–16, 240, 242 agomoni 148 Asom Jatiya Mahasabha 193 Agunpakhi 223, 225 Azad 199 Agrarian movements 16, 75–76, 234, Babughat 121 236–37 Bagerhat 158 Ahmed, Muzzaffar 83–84 Bandopadhyay, Ateen 19–21, 74, 93, 95, Akhyan 144, 146 102, 115 Alamer Nijer Baari 204 Bandopadhyay, Bibhutibhushan 29, 124, Ali, Agha Shahid 220 223–24 All India Congress Party 36–37, 40, 48–50, Bandopadhyay, Hiranmoy 30, 122, 149–51 73, 76, 86, 119, 125, 133, 137, 176 Bandopadhyay, Manik 17, 18, 34, 42, 44– All India Women’s Conference (AIWC) 70, 46, 48–51, 57–58, 60, 66–67, 154, 208 72, 74, 86–87, 92, 112–13, 120 Bandopadhyay, Shekhar 64, 66 Amin, Shahid 29 Bandopadhyay, Sibaji 215, 217–19 Anandamath 13, 208, 210 Bandopadhyay, Tarashankar 10–11, 17, 33, 57–58, 60–61, 63, 67, 116, 208 Anderson, Benedict 71, 220 Banerjee, Himani 187, 246 Anyo Gharey Anyo Swar 205 Banerjee, Paula 34, 248 Andul 121 Banerjee, Suresh Chandra 37 Ansars 158, 190–91 Bangla fiction 2, 60, 93, 117, 131, 165, Anti ‘Tonko’ movement 191 170, 194–95 Amrita Bazar Patrika 122, 158–60, 162, 190 Bangla literature 1, 14, 188 Ananda Bazar Patrika 181, 186 Bangla novel 11, 13, 57, 75, 146–47, 179 Aro Duti Mrityu 202, 217 Bangla partition fiction 3, 12, 18, 157, 168, Aronyak 224 226, 247 Arjun 16, 19, 142–45, 155 Bangladesh War of 1971 -

An Urban River on a Gasping State: Dilemma on Priority of Science, Conscience and Policy

An urban river on a gasping state: Dilemma on priority of science, conscience and policy Manisha Deb Sarkar Former Associate Professor Department of Geography Women’s Christian College University of Calcutta 6, Greek Church Row Kolkata - 700026 SKYLINE OF KOLKATA METROPOLIS KOLKATA: The metropolis ‘Adi Ganga: the urban river • Human settlements next to rivers are the most favoured sites of habitation. • KOLKATA selected to settle on the eastern bank of Hughli River – & •‘ADI GANGA’, a branched out tributary from Hughli River, a tidal river, favoured to flow across the southern part of Kolkata. Kolkata – View from River Hughli 1788 ADI GANGA Present Transport Network System of KOLKATA Adi Ganga: The Physical Environment & Human Activities on it: PAST & PRESNT Adi Ganga oce upo a tie..... (British period) a artists ipressio Charles Doyle (artist) ‘Adi Ganga’- The heritage river at Kalighat - 1860 Width of the river at this point of time Adi Ganga At Kalighat – 1865 source: Bourne & Shepard Photograph of Tolly's Nullah or Adi Ganga near Kalighat from 'Views of Calcutta and Barrackpore' taken by Samuel Bourne in the 1860s. The south-eastern Calcutta suburbs of Alipore and Kalighat were connected by bridges constructed over Tolly's Nullah. Source: British Library ’ADI Ganga’ & Kalighat Temple – an artists ipressio in -1887 PAST Human Activities on it: 1944 • Transport • Trade • Bathing • Daily Domestic Works • Performance of Religious Rituals Present Physical Scenario of Adi Ganga (To discern the extant physical condition and spatial scales) Time Progresses – Adi Ganga Transforms Laws of Physical Science Tidal water flow in the river is responsible for heavy siltation in the river bed. -

Uhm Phd 9519439 R.Pdf

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality or the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely. event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor. MI48106·1346 USA 313!761-47oo 800:521-0600 Order Number 9519439 Discourses ofcultural identity in divided Bengal Dhar, Subrata Shankar, Ph.D. University of Hawaii, 1994 U·M·I 300N. ZeebRd. AnnArbor,MI48106 DISCOURSES OF CULTURAL IDENTITY IN DIVIDED BENGAL A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN POLITICAL SCIENCE DECEMBER 1994 By Subrata S. -

Divya Sandesha

DIVYA SANDESHA Pujya Shri Ramchandraji Maharaj’s (Shri Babuji) letters to Sri S.A.Sarnadji Divya Sandesh: A Collection of letters of Pujya Shri Ramchandraji Maharaj (Shri Babuji) of Shahjahanpur to Shri (Late) S.A.Sarnadji, edited by Smt. Shakuntala Bai Sarnad and published by Shree Prakashana, NGO Colony, Jewargi Road, Gulbarga. PUBLISHER’S NOTE After the demise of Sri S.A.Sarnadji, while searching the papers of old house at our village and other immoveable property, we could find a bunch of letters and few Sanskrit books kept safely. These letters are in Urdu, Hindi and English. We learnt that Urdu letters are written/got written by Pujya Babuji Maharaj to Sarnadji. The other letters are written by Sri Ishwar Sahaji, Sri Raghavendra Raoji and Dr. K.C Vardachariji. We were inspired by these letters and thought of publishing Pujya Babuji’s letters with translations so as abhyasi brothers and sisters would be benifited and they can see the original hand writings of a great special personality Pujya Babuji Maharaj. We felt irrelevent since these letters are written to Sarnadji in a personal capacity and not as an office bearer. Probably Sarnadji must have thought likewise and did not take any interst in this regard and moreover none of our family members was aware of these letters. Though these letters are personal, the need to publish the letters with translations was felt to enable the true seekers of spirituality to perceive the message of love, advice and guidance embodied therein lest these letters written in formative years of a Sadhaka with humility, compassion and concern by Pujaya Babuji Maharaj may be lost for ever. -

Dr. Manoj Kumar Assistant Professor

Dr. Manoj Kumar Assistant Professor ( Department of Political Science ) G.D. College, Begusarai ( L.N.M.U. Darbhanga) M.N. – 9532258109 Email- [email protected] Socio-Political Thoughts of Swami Vivekananda The ideas of Vivekananda cover almost all aspects of socio-political developments. We can make a list on which Vivekananda had given his remarks time and again: – i. Upholding nationalism ii. Implementation of Vedantic system of education. iii. Achieving social justice and a system of equal opportunity. iv. Steps towards socialism particularly achieving the concept of spiritual socialism. v. Development of marginalised classes (Dalits & untouchables) by adopting reasonable classification. vii. Steps towards secularism. All these ideas are similar to those enshrined in the preamble & fundamental rights chapter. The makers of Indian Constitution were much influenced by speeches and writings of Vivekananda. Therefore they incorporated the philosophies of Vivekananda while drafting Indian Constitution. The Constituent Assembly Members had repeatedly mentioned Vivekananda while debating on new provisions of Constitution, particularly in support of the philosophy behind the preamble and fundamental rights. The 19th century witnessed the dawn of renaissance in Bengal. Luminaries like Rammohan Roy, Debendranath Tagore, Iswar Chandra vidhyasagar introduced new ideas of social reforms. They started open protest against the social vices of the contemporary society. Rammohan Roy, who was considered as the ‗prophet of new India‘5 introduced the spirit of liberty, equality and fraternity in his religious and social reforms6 argued for modernisation of education, abolishment of social evils like sati, child marriage etc. Vidhyasagar, on the other hand, strongly agitated for adoption of a system of widow marriage in contemporary Bengali society. -

NDA Exam History Mcqs

1500+ HISTORY QUESTIONS FOR AFCAT/NDA/CDS shop.ssbcrack.com shop.ssbcrack.com _________________________________________ ANCIENT INDIA : QUESTIONS WITH ANSWERS _________________________________________ 1. Which of the following Vedas deals with magic spells and witchcraft? (a) Rigveda (b) Samaveda (c) Yajurveda (d) Atharvaveda Ans: (d) 2. The later Vedic Age means the age of the compilation of (a) Samhitas (b) Brahmanas (c) Aranyakas (d) All the above Ans: (d) 3. The Vedic religion along with its Later (Vedic) developments is actually known as (a) Hinduism (b) Brahmanism shop.ssbcrack.com (c) Bhagavatism (d) Vedic Dharma Ans: (b) 4. The Vedic Aryans first settled in the region of (a) Central India (b) Gangetic Doab (c) Saptasindhu (d) Kashmir and Punjab Ans: (c) 5. Which of the following contains the famous Gayatrimantra? (a) Rigveda (b) Samaveda (c) Kathopanishad (d) Aitareya Brahmana shop.ssbcrack.com Ans: (a) 6. The famous Gayatrimantra is addressed to (a) Indra (b) Varuna (c) Pashupati (d) Savita Ans: (d) 7. Two highest ,gods in the Vedic religion were (a) Agni and Savitri (b) Vishnu and Mitra (c) Indra and Varuna (d) Surya and Pushan Ans: (c) 8. Division of the Vedic society into four classes is clearly mentioned in the (a) Yajurveda (b) Purusa-sukta of Rigveda (c) Upanishads (d) Shatapatha Brahmana Ans: (b) 9. This Vedic God was 'a breaker of the forts' and also a 'war god' (a) Indra (b) Yama (c) Marut shop.ssbcrack.com (d) Varuna Ans: (a) 10. The Harappan or Indus Valley Civilisation flourished during the ____ age. (a) Megalithic (b) Paleolithic (c) Neolithic (d) Chalcolithic Ans: (d) 11. -

VIVEKANANDA and the ART of MEMORY June 26, 1994 M. Ram Murty, FRSC1

VIVEKANANDA AND THE ART OF MEMORY June 26, 1994 M. Ram Murty, FRSC1 1. Episodes from Vivekananda’s life 2. Episodes from Ramakrishna’s life 3. Their memory power compared by Swami Saradananda 4. Other srutidharas from the past 5. The ancient art of memory 6. The laws of memory 7. The role of memory in daily life Episodes from Vivekananda’s life The human problem is one of memory. We have forgotten our divine nature. All the great teachers of the past have declared that the revival of the memory of our divinity is the paramount goal. Memory is a faculty and as such, it is neither good nor bad. Every action that we do, every thought that we think, leaves an indelible trail of memory. Whether we remember or not, the contents are recorded and affect our daily life. Therefore, an awareness of this faculty and its method of operation is vital for healthy existence. Properly employed, it leads us to enlightenment; abused or misused, it can torment us. So we must learn to use it properly, to strengthen it for our own improvement. In studying the life of Vivekananda, we come across many phenomenal examples of his amazing faculty of memory. In ‘Reminiscences of Swami Vivekananda,’ Haripada Mitra relates the following story: One day, in the course of a talk, Swamiji quoted verbatim some two or three pages from Pickwick Papers. I wondered at this, not understanding how a sanyasin could get by heart so much from a secular book. I thought that he must have read it quite a number of times before he took orders. -

Why I Became a Hindu

Why I became a Hindu Parama Karuna Devi published by Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Copyright © 2018 Parama Karuna Devi All rights reserved Title ID: 8916295 ISBN-13: 978-1724611147 ISBN-10: 1724611143 published by: Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Website: www.jagannathavallabha.com Anyone wishing to submit questions, observations, objections or further information, useful in improving the contents of this book, is welcome to contact the author: E-mail: [email protected] phone: +91 (India) 94373 00906 Please note: direct contact data such as email and phone numbers may change due to events of force majeure, so please keep an eye on the updated information on the website. Table of contents Preface 7 My work 9 My experience 12 Why Hinduism is better 18 Fundamental teachings of Hinduism 21 A definition of Hinduism 29 The problem of castes 31 The importance of Bhakti 34 The need for a Guru 39 Can someone become a Hindu? 43 Historical examples 45 Hinduism in the world 52 Conversions in modern times 56 Individuals who embraced Hindu beliefs 61 Hindu revival 68 Dayananda Saraswati and Arya Samaj 73 Shraddhananda Swami 75 Sarla Bedi 75 Pandurang Shastri Athavale 75 Chattampi Swamikal 76 Narayana Guru 77 Navajyothi Sree Karunakara Guru 78 Swami Bhoomananda Tirtha 79 Ramakrishna Paramahamsa 79 Sarada Devi 80 Golap Ma 81 Rama Tirtha Swami 81 Niranjanananda Swami 81 Vireshwarananda Swami 82 Rudrananda Swami 82 Swahananda Swami 82 Narayanananda Swami 83 Vivekananda Swami and Ramakrishna Math 83 Sister Nivedita -

Visva-Bharati, Santiniketan Title Accno Language Author / Script Folios DVD Remarks

www.ignca.gov.in Visva-Bharati, Santiniketan Title AccNo Language Author / Script Folios DVD Remarks CF, All letters to A 1 Bengali Many Others 75 RBVB_042 Rabindranath Tagore Vol-A, Corrected, English tr. A Flight of Wild Geese 66 English Typed 112 RBVB_006 By K.C. Sen A Flight of Wild Geese 338 English Typed 107 RBVB_024 Vol-A A poems by Dwijendranath to Satyendranath and Dwijendranath Jyotirindranath while 431(B) Bengali Tagore and 118 RBVB_033 Vol-A, presenting a copy of Printed Swapnaprayana to them A poems in English ('This 397(xiv Rabindranath English 1 RBVB_029 Vol-A, great utterance...') ) Tagore A song from Tapati and Rabindranath 397(ix) Bengali 1.5 RBVB_029 Vol-A, stage directions Tagore A. Perumal Collection 214 English A. Perumal ? 102 RBVB_101 CF, All letters to AA 83 Bengali Many others 14 RBVB_043 Rabindranath Tagore Aakas Pradeep 466 Bengali Rabindranath 61 RBVB_036 Vol-A, Tagore and 1 www.ignca.gov.in Visva-Bharati, Santiniketan Title AccNo Language Author / Script Folios DVD Remarks Sudhir Chandra Kar Aakas Pradeep, Chitra- Bichitra, Nabajatak, Sudhir Vol-A, corrected by 263 Bengali 40 RBVB_018 Parisesh, Prahasinee, Chandra Kar Rabindranath Tagore Sanai, and others Indira Devi Bengali & Choudhurani, Aamar Katha 409 73 RBVB_029 Vol-A, English Unknown, & printed Indira Devi Aanarkali 401(A) Bengali Choudhurani 37 RBVB_029 Vol-A, & Unknown Indira Devi Aanarkali 401(B) Bengali Choudhurani 72 RBVB_029 Vol-A, & Unknown Aarogya, Geetabitan, 262 Bengali Sudhir 72 RBVB_018 Vol-A, corrected by Chhelebele-fef. Rabindra- Chandra -

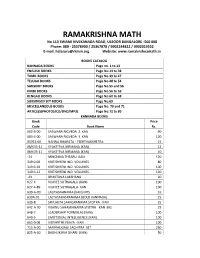

Halasuru Math Book List

RAMAKRISHNA MATH No.113 SWAMI VIVEKANADA ROAD, ULSOOR BANGALORE -560 008 Phone: 080 - 25578900 / 25367878 / 9902244822 / 9902019552 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.ramakrishnamath.in BOOKS CATALOG KANNADA BOOKS Page no. 1 to 13 ENGLISH BOOKS Page No.14 to 38 TAMIL BOOKS Page No.39 to 47 TELUGU BOOKS Page No.48 to 54 SANSKRIT BOOKS Page No.55 and 56 HINDI BOOKS Page No.56 to 59 BENGALI BOOKS Page No.60 to 68 SUBSIDISED SET BOOKS Page No.69 MISCELLANEOUS BOOKS Page No. 70 and 71 ARTICLES(PHOTOS/CD/DVD/MP3) Page No.72 to 80 KANNADA BOOKS Book Price Code Book Name Rs. 002-6-00 SASWARA RIGVEDA 2 KAN 90 003-4-00 SASWARA RIGVEDA 3 KAN 120 05951-00 NANNA BHARATA - TEERTHAKSHETRA 15 0MK35-11 VYAKTITVA NIRMANA (KAN) 12 0MK35-11 VYAKTITVA NIRMANA (KAN) 10 -24 MINCHINA THEARU KAN 120 349.0-00 KRITISHRENI IND. VOLUMES 80 349.0-10 KRITISHRENI IND. VOLUMES 100 349.0-12 KRITISHRENI IND. VOLUMES 120 -43 BHAKTANA LAKSHANA 20 627-4 VIJAYEE SUTRAGALU (KAN) 100 627-4-89 VIJAYEE SUTRAGALA- KAN 100 639-A-00 LALITASAHNAMA (KAN) MYS 16 639A-01 LALTASAHASRANAMA (BOLD KANNADA) 25 639-B SRI LALITA SAHASRANAMA STOTRA - KAN 25 642-A-00 VISHNU SAHASRANAMA STOTRA - KAN BIG 25 648-7 LEADERSHIP FORMULAS (KAN) 100 649-5 EMOTIONAL INTELLIGENCE (KAN) 100 663-0-08 VIDYARTHI VIJAYA - KAN 100 715-A-00 MAKKALIGAGI SACHITRA SET 250 825-A-00 BADHUKUVA DHARI (KAN) 50 840-2-40 MAKKALA SRI KRISHNA - 2 (KAN) 40 B1039-00 SHIKSHANA RAMABANA 6 B4012-00 SHANDILYA BHAKTI SUTRAS 75 B4015-03 PHIL.