Buddhist Philosophy: Principle and Practice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Issue 21 Spring 2016 Digital & Print-On-Demand

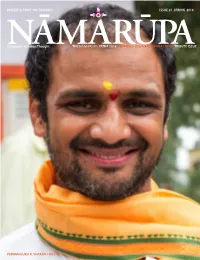

DIGITAL & PRINT-ON-DEMAND ISSUE 21 SPRING 2016 NĀMARŪPACategories of Indian Thought THE NĀMARŪPA YATRA 2015 ASHTANGA YOGA SADHANA RETREAT TRIBUTE ISSUE PARAMAGURU R. SHARATH JOIS NĀMARŪPA ISSUE 21 SPRING 2016 Categories of Indian Thought THE NĀMARŪPA YATRA 2015 ASHTANGA YOGA SADHANA RETREAT TRIBUTE ISSUE Publishers & Founding Editors Robert Moses & Eddie Stern NĀMARŪPA YATRA 2015 4 THE POSTER & ROUTE MAP Advisors Dr. Robert E. Svoboda GROUP PHOTOGRAPH 6 NĀMARŪPA YATRA 2015 Meenakshi Moses PALLAVI SHARMA DUFFY 8 WELCOME SPEECH Jocelyne Stern During the Folk Festival at Editors Vishnudevananda Tapovan Kuti Eddie Stern & Meenakshi Moses Design & Production Robert Moses PARAMAGURU 10 CONFERENCES AT TAPOVAN KUTI Proofreading & Transcription R. SHARATH JOIS Transcriptions of talks after class Meenakshi Moses Melanie Parker ROBERT MOSES 28 PHOTO ESSAY Megan Weaver Ashtanga Yoga Sadhana Retreat October 2015 Meneka Siddhu Seetharaman Website www.namarupa.org by BRAHMA VIDYA PEETH Roberto Maiocchi & Robert Moses ACHARYAS 48 TALKS ON INDIAN CULTURE All photographs in Issue 21 SWAMI SHARVANANDA Robert Moses except where noted. SWAMI HARIBRAMENDRANANDA Cover: R. Sharath Jois at Vishwanath Mandir, Uttarkashi, Himalayas. SWAMI MITRANANDA 58 NAVARATRI Back cover: Welcome sign at Kashi Vishwanath Mandir, Uttarkashi. SUAN LIN 62 FINE ART PHOTOGRAPHS October 13, 2015. Analog photography during Yatra 2015 SATYA MOSES DAŚĀVATĀRA ILLUSTRATIONS NĀMARŪPA Categories of Indian Thought, established in 2003, honors the many systems of knowledge, prac- tical and theoretical, that have origi- nated in India. Passed down through अ आ इ ई उ ऊ the ages, these systems have left tracks, a ā i ī u ū paths already traveled that can guide ए ऐ ओ औ us back to the Self—the source of all e ai o au names NĀMA and forms RŪPA. -

Gerontocracy of the Buddhist Monastic Administration in Thailand

Simulacra | ISSN: 2622-6952 (Print), 2656-8721 (Online) https://journal.trunojoyo.ac.id/simulacra Volume 4, Issue 1, June 2021 Page 43–56 Gerontocracy of the Buddhist monastic administration in Thailand Jesada Buaban1* 1 Indonesian Consortium for Religious Studies, Universitas Gadjah Mada, Indonesia * Corresponding author E-mail address: [email protected] DOI: https://doi.org/10.21107/sml.v4i1.9880 Article Info Abstract Keywords: This paper examines the monastic administration in Thai Buddhism, dhamma studies which is ruled by the senior monks and supported by the government. It aims to answer two questions; (1) why the Sangha’s administration has gerontocracy been designed to serve the bureaucratic system that monks abandon social Sangha Council and political justices, and (2) how the monastic education curriculum are secularism designed to support such a conservative system. Ethnographic methodology Thai Buddhism was conducted and collected data were analyzed through the concept of gerontocracy. It found that (1) Thai Buddhism gains supports from the government much more than other religions. Parallel with the state’s bureaucratic system, the hierarchical conservative council contains the elderly monks. Those committee members choose to respond to the government policy in order to maintain supports rather than to raise social issues; (2) gerontocracy is also facilitated by the idea of Theravada itself. In both theory and practice, the charismatic leader should be the old one, implying the condition of being less sexual feeling, hatred, and ignorance. Based on this criterion, the moral leader is more desirable than the intelligent. The concept of “merits from previous lives” is reinterpreted and reproduced to pave the way for the non-democratic system. -

The Mind-Body in Pali Buddhism: a Philosophical Investigation

The Mind-Body Relationship In Pali Buddhism: A Philosophical Investigation By Peter Harvey http://www.buddhistinformation.com/mind.htm Abstract: The Suttas indicate physical conditions for success in meditation, and also acceptance of a not-Self tile-principle (primarily vinnana) which is (usually) dependent on the mortal physical body. In the Abhidhamma and commentaries, the physical acts on the mental through the senses and through the 'basis' for mind-organ and mind-consciousness, which came to be seen as the 'heart-basis'. Mind acts on the body through two 'intimations': fleeting modulations in the primary physical elements. Various forms of rupa are also said to originate dependent on citta and other types of rupa. Meditation makes possible the development of a 'mind-made body' and control over physical elements through psychic powers. The formless rebirths and the state of cessation are anomalous states of mind-without-body, or body-without-mind, with the latter presenting the problem of how mental phenomena can arise after being completely absent. Does this twin-category process pluralism avoid the problems of substance- dualism? The Interaction of Body and Mind in Spiritual Development In the discourses of the Buddha (Suttas), a number of passages indicate that the state of the body can have an impact on spiritual development. For example, it is said that the Buddha could only attain the meditative state of jhana once he had given up harsh asceticism and built himself up by taking sustaining food (M.I. 238ff.). Similarly, it is said that health and a good digestion are among qualities which enable a person to make speedy progress towards enlightenment (M.I. -

Style and Ascetics: Attractiveness, Power and the Thai Sangha

Style and Ascetics: Attractiveness, Power and the Thai Sangha Natayada na Songkhla School of Oriental and African Studies Ph.D. Thesis ProQuest Number: 11015841 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is d ep en d en t upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely even t that the author did not send a com p lete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be rem oved, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 11015841 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 4 8 1 0 6 - 1346 Abstract The majority of research for this thesis took place during the Thai general election of 1988 when the new religious movements Santi Asoke and Wat Dhammakaya were subject to investigation for political activity despite, respectively, defiance or denial. The relationship between the Thai Sangha and lay devotees is examined in order to discover how it is that Thai monks, whom many researchers find powerless, can be accused of political activity. In the past, monks have been used to legitimate lay political leaders and have taken active roles in local leadership. This thesis aims to determine whether monks in Thailand have power and, if they do, how such power becomes politically threatening to the status quo. -

Buddhism and Responses to Disability, Mental Disorders and Deafness in Asia

Buddhism and Responses to Disability, Mental Disorders and Deafness in Asia. A bibliography of historical and modern texts with introduction and partial annotation, and some echoes in Western countries. [This annotated bibliography of 220 items suggests the range and major themes of how Buddhism and people influenced by Buddhism have responded to disability in Asia through two millennia, with cultural background. Titles of the materials may be skimmed through in an hour, or the titles and annotations read in a day. The works listed might take half a year to find and read.] M. Miles (compiler and annotator) West Midlands, UK. November 2013 Available at: http://www.independentliving.org/miles2014a and http://cirrie.buffalo.edu/bibliography/buddhism/index.php Some terms used in this bibliography Buddhist terms and people. Buddhism, Bouddhisme, Buddhismus, suffering, compassion, caring response, loving kindness, dharma, dukkha, evil, heaven, hell, ignorance, impermanence, kamma, karma, karuna, metta, noble truths, eightfold path, rebirth, reincarnation, soul, spirit, spirituality, transcendent, self, attachment, clinging, delusion, grasping, buddha, bodhisatta, nirvana; bhikkhu, bhikksu, bhikkhuni, samgha, sangha, monastery, refuge, sutra, sutta, bonze, friar, biwa hoshi, priest, monk, nun, alms, begging; healing, therapy, mindfulness, meditation, Gautama, Gotama, Maitreya, Shakyamuni, Siddhartha, Tathagata, Amida, Amita, Amitabha, Atisha, Avalokiteshvara, Guanyin, Kannon, Kuan-yin, Kukai, Samantabhadra, Santideva, Asoka, Bhaddiya, Khujjuttara, -

31 Planes of Existence (1)

31 Planes of Existence (1) Kamaloka Realms Death & Rebirth All putthujjhanas are subjected to death & rebirths “Death proximate kamma” or last thoughts moment leads to the realm of rebirth. Good or bad, it tends to be the state of mind characteristic of the being in his previous life It could be hate, metta, karuna, tanha, and so on. Tanha is the one that binds us to Samsara, esp the sensual worlds Depends on 3 types of action (mental, physical & vocal manifesting in thought, action & speech) Purified consciousness leads to birth in higher planes such as Brahma lokas Mixed type will lead to birth in the intermediate planes of kama lokas Predominantly bad kamma will lead to birth in the Duggatti (unhappy states) 1 Only humans on earth? Early Buddhist texts (Nikaya), mentioned: “the thousandfold world system” “the twice thousandfold world system” “the thrice thousandfold world system” Buddhaghosa said there are 1,000,000,000,000 world systems 3 Types of Worlds Kama-loka or kamabhava (sensuous world) 11 planes Rupa-loka or rupabhava (the world of form or fine material world) 16 planes Arupa-loka or arupabhava (the formless world / immaterial world) 4 planes 2 Kama-Loka The sensuous world is divided into Kamaduggati (those states that are not desirable and unsatisfactory with unpleasant and painful feelings) Kamasugati (those states that are desirable or satisfying with pleasant and pleasurable feelings) Kamaduggati Bhumi 4 States of Suffering (Apaya) Niraya (Hell) Tiracchana Yoni (Animals) Peta Loka (Hungry ghosts) Asura (Demons) 3 Niraya (Hell) Lowest level of existence with Devoid of sukha. Only non-stop unimaginable suffering & anguish Dukha. -

Myanmar Buddhism of the Pagan Period

MYANMAR BUDDHISM OF THE PAGAN PERIOD (AD 1000-1300) BY WIN THAN TUN (MA, Mandalay University) A THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY SOUTHEAST ASIAN STUDIES PROGRAMME NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF SINGAPORE 2002 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my gratitude to the people who have contributed to the successful completion of this thesis. First of all, I wish to express my gratitude to the National University of Singapore which offered me a 3-year scholarship for this study. I wish to express my indebtedness to Professor Than Tun. Although I have never been his student, I was taught with his book on Old Myanmar (Khet-hoà: Mranmâ Râjawaà), and I learnt a lot from my discussions with him; and, therefore, I regard him as one of my teachers. I am also greatly indebted to my Sayas Dr. Myo Myint and Professor Han Tint, and friends U Ni Tut, U Yaw Han Tun and U Soe Kyaw Thu of Mandalay University for helping me with the sources I needed. I also owe my gratitude to U Win Maung (Tampavatî) (who let me use his collection of photos and negatives), U Zin Moe (who assisted me in making a raw map of Pagan), Bob Hudson (who provided me with some unpublished data on the monuments of Pagan), and David Kyle Latinis for his kind suggestions on writing my early chapters. I’m greatly indebted to Cho Cho (Centre for Advanced Studies in Architecture, NUS) for providing me with some of the drawings: figures 2, 22, 25, 26 and 38. -

Chapter-N Cetasika (Mental Factors) 2.0. Introduction

44 Chapter-n Cetasika (Mental Factors) 2.0. Introduction In the first chapter, Citta (Consciousness) has been introduced. In this chapter, Cetasika (Mental factors) which means depending on citta will be discussed in detail with reference to the Abhidhamma pitaka by dividing topics and subtopics related to the present chapter. In the eighty-nine types of consciousness, enumerated in the first chapter, fifty-two mental factors arise in varying degree.There are seven concomitants common to every consciousness. There are six others that may or may not arise in each and every consciousness. They are termed Pakinnakas or Ethically variable factors. All these thirteen are designated Annasamanas, a rather peculiar technical term. Anna means other, samana means common. Sobhanas (Good), when compared with Asobhanas (Evil), are called Aiina (other) 'being of the opposite category'. Thus the Asobhanas are in contradistinction to Sobhanas. These thirteen become moral or immoral according to the types of consciousness in which they occur. 45 The fourteen concomitants are invariably found in every type of immoral consciousness. The nineteen are common to all type of moral consciousness. The six are moral concomitants which occur as occasion arises. Therefore these fifty-two (7+6+14+19+6=52) are found in all the types of consciousness in different proportions. In this chapter all the 52- mental factors are enumerated and classified. Every type of consciousness is microscopically analysed, and the accompanying psychic factors are given in details. The types of consciousness in which each mental factor occurs, is also described. 2.1. Definition of Cetasika Cetasika=cetas+ika When citta arises, it arises with mental factors that depend on it. -

Bridging Worlds: Buddhist Women's Voices Across Generations

BRIDGING WORLDS Buddhist Women’s Voices Across Generations EDITED BY Karma Lekshe Tsomo First Edition: Yuan Chuan Press 2004 Second Edition: Sakyadhita 2018 Copyright © 2018 Karma Lekshe Tsomo All rights reserved No part of this book may not be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, or by any information storage or retreival system, without the prior written permission from the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations. Cover Illustration, "Woman on Bridge" © 1982 Shig Hiu Wan. All rights reserved. "Buddha" calligraphy ©1978 Il Ta Sunim. All rights reserved. Chapter Illustrations © 2012 Dr. Helen H. Hu. All rights reserved. Book design and layout by Lillian Barnes Bridging Worlds Buddhist Women’s Voices Across Generations EDITED BY Karma Lekshe Tsomo 7th Sakyadhita International Conference on Buddhist Women With a Message from His Holiness the XIVth Dalai Lama SAKYADHITA | HONOLULU, HAWAI‘I iv | Bridging Worlds Contents | v CONTENTS MESSAGE His Holiness the XIVth Dalai Lama xi ACKNOWLEDGMENTS xiii INTRODUCTION 1 Karma Lekshe Tsomo UNDERSTANDING BUDDHIST WOMEN AROUND THE WORLD Thus Have I Heard: The Emerging Female Voice in Buddhism Tenzin Palmo 21 Sakyadhita: Empowering the Daughters of the Buddha Thea Mohr 27 Buddhist Women of Bhutan Tenzin Dadon (Sonam Wangmo) 43 Buddhist Laywomen of Nepal Nivedita Kumari Mishra 45 Himalayan Buddhist Nuns Pacha Lobzang Chhodon 59 Great Women Practitioners of Buddhadharma: Inspiration in Modern Times Sherab Sangmo 63 Buddhist Nuns of Vietnam Thich Nu Dien Van Hue 67 A Survey of the Bhikkhunī Saṅgha in Vietnam Thich Nu Dong Anh (Nguyen Thi Kim Loan) 71 Nuns of the Mendicant Tradition in Vietnam Thich Nu Tri Lien (Nguyen Thi Tuyet) 77 vi | Bridging Worlds UNDERSTANDING BUDDHIST WOMEN OF TAIWAN Buddhist Women in Taiwan Chuandao Shih 85 A Perspective on Buddhist Women in Taiwan Yikong Shi 91 The Inspiration ofVen. -

The Mission Accomplished

TheThe MissionMission AccomplishedAccomplished Ven. Pategama Gnanarama Ph.D. HAN DD ET U 'S B B O RY eOK LIBRA E-mail: [email protected] Web site: www.buddhanet.net Buddha Dharma Education Association Inc. The Mission Accomplished A historical analysis of the Mahaparinibbana Sutta of the Digha Nikaya of the Pali Canon. by Ven. Pategama Gnanarama Ph. D. The Mission Accomplished is undoubtedly an eye opening contribution to Bud- dhist analytical Pali studies. In this analytical and critical work Ven. Dr. Pate- gama Gnanarama enlightens us in many areas of subjects hitherto unexplored by scholars. His views on the beginnings of the Bhikkhuni Order are interesting and refreshing. They might even be provocative to traditional readers, yet be challenging to the feminists to adopt a most positive attitude to the problem. Prof. Chandima Wijebandara University of Sri Jayawardhanapura Sri Lanka. A masterly treatment of a cluster of Buddhist themes in print Senarat Wijayasundara Buddhist and Pali College Singapore Published by Ti-Sarana Buddhist Association 90, Duku Road. Singapore 429254 Tel: 345 6741 First published in Singapore, 1997 Published by Ti-Sarana Buddhist Association ISBN: 981–00–9087–0 © Pategama Gnanarama 1997 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval systems or technologies now known or later developed, without per- mission in writing from the publisher. Cover: Mahaparinibbana; an ancient stone carving from Gandhara — Loriyan Tangai. Photograph reproduced by Mr K. C. Wong. Contents Introductory . 8 Chapter 1: The Mahaparinibbana Sutta & its Different Versions . -

Com 23 Draft B

Community Issue 23 - Page 1 Autumn 2005 / 2548 The Upāsaka & Upāsikā Newsletter Issue No. 23 Dagoba at Mahintale Dagoba InIn thisthis issue.......issue....... InIn peoplepeople wewe trusttrust ?? TheThe Temple at Kosgoda The wisdom of the heartheart SicknessSickness——A Teacher AssistedAssisted DyingDying MakingMaking connectionsconnections beyond words BluebellBluebell WalkWalk Community Community Issue 23 - Page 2 In people we trust? Multiculturalism and community relations have been This is a thoroughly uncomfortable position to be in, as much in the news over recent months. The tragedy of anyone who has suffered from arbitrary discrimination can the London bombings and the spotlight this has attest. There is a feeling of helplessness that whatever one thrown on to what is called ‘the Moslem community’ says or does will be misinterpreted. There is a resentment has led me to reflect upon our own Buddhist that one is being treated unfairly. Actions that would pre- ‘community’. Interestingly, the name of this newslet- viously have been taken at face value are now suspected of ter is ‘Community’, and this was chosen in discussion having a hidden agenda in support of one’s group. In this between a number of us, because it reflected our wish situation, rumour and gossip tend to flourish, and attempts to create a supportive and inclusive network of Forest to adopt a more inclusive position may be regarded with Sangha Buddhist practitioners. suspicion, or misinterpreted to fit the stereotype. The AUA is predominantly supported by western Once a community has polarised, it can take a great deal converts to Buddhism. Some of those who frequent of work to re-establish trust. -

Bhavana Vandana

BhavanaBhavana VVandaanda BookBook ofof DevotionDevotion Compiled by H. Gunaratana Mahathera HAN DD ET U 'S B B O RY eOK LIBRA E-mail: [email protected] Web site: www.buddhanet.net Buddha Dharma Education Association Inc. Bhàvanà Vandanà Book of Devotion Compiled By H. Gunaratana Mahathera Bhàvanà Society Meditation Center Bhàvanà Vandanà Book of Devotion Compiled By H. Gunaratana Mahathera Copyright © 1990 by Bhàvanà Society All rights reserved R D : T C B B E F R F, , H C S. R. S T T R.O.C. T: () F: () T O C P ......................................................................................................................... iixx P ........................................................................................ x I ....................................................................................................... H .......................................................................... O V A ................................. T W S ........................................................................... F I V ................................................ S D ............................................ F U ....................................................... – F P ........................................................................................... Tisaraõa and Uposatha Sīla .............................................................................. R R P ............................ Pañcasīla ...............................................................................................................................