Resolutions Adopted

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gulnara Shahinian and Democracy Today Armenia Are Awarded the Anita Augspurg Prize "Women Rebels Against War"

Heidi Meinzolt Laudatory speech, September 21 in Verden: Gulnara Shahinian and Democracy today Armenia are awarded the Anita Augspurg Prize "Women rebels against war". Ladies and gentlemen, dear friends, dear Gulnara, We are celebrating for the second time the Anita Augspurg Award "Women rebels against war". Today, exactly 161 years ago, the women's rights activist Anita Augspurg was born here in Verden. Her memory is cherished by many dedicated people here, in Munich, where she lived and worked for many years, and internationally as co-founder of our organization of the "International Women's League for Peace and Freedom" more than 100 years ago With this award we want to honour and encourage women who are committed to combating militarism and war and strive for women’s rights and Peace. On behalf of the International Women's League for Peace and Freedom, I want to thank all those who made this award ceremony possible. My special thanks go to: Mayor Lutz Brockmann, Annika Meinecke, the city representative for equal opportunities members of the City Council of Verden, all employees of the Town Hall, all supporters, especially the donors our international guests from Ukraine, Kirgistan, Italy, Sweden, Georgia who are with us today because we have an international meeting of the Civic Solidarity Platform of OSCE this weekend in Hamburg and last but not least Irmgard Hofer , German president of WILPF in the name of all present WILPFers Before I talk more about our award-winner, I would like to begin by reminding you the life and legacy of Anita Augspurg, with a special focus on 1918, exactly 100 years ago. -

Innovative Means to Promote Peace During World War I. Julia Grace Wales and Her Plan for Continuous Mediation

Master’s Degree programme in International Relations Second Cycle (D.M. 270/2004) Final Thesis Innovative Means to Promote Peace During World War I. Julia Grace Wales and Her Plan for Continuous Mediation. Supervisor Ch. Prof. Bruna Bianchi Assistant supervisor Ch. Prof. Geraldine Ludbrook Graduand Flaminia Curci Matriculation Number 860960 Academic Year 2017 / 2018 ABSTRACT At the breakout of World War I many organizations for promoting peace emerged all over the world and in the United States as well, especially after the subsequent American declaration of war in April 1917. Peace movements began to look for new means for settling the dispute, and a large contribution was offered by women. World War I gave women the chance to rise their public acknowledgment and to increase their rights through war-related activities. The International Congress of Women at The Hague held in April 1915, demonstrates the great ability of women in advocating peace activities. Among the resolutions adopted by Congress stands out the Plan for Continuous Mediation without Armistice theorized by the Canadian peace activist Julia Grace Wales (see Appendix II). This thesis intends to investigate Julia Grace Wales’ proposal for a Conference of neutral nations for continuous and independent mediation without armistice. After having explored women’s activism for peace in the United States with a deep consideration to the role of women in Canada, the focus is addressed on a brief description of Julia Grace Wales’ life in order to understand what factors led her to conceive such a plan. Through the analysis of her plan and her writings it is possible to understand that her project is not only an international arbitration towards the only purpose of welfare, but also an analysis of the conditions that led to war so as to change them for avoiding future wars. -

Gender and Colonial Politics After the Versailles Treaty

Wildenthal, L. (2010). Gender and Colonial Politics after the Versailles Treaty. In Kathleen Canning, Kerstin Barndt, and Kristin McGuire (Eds.), Weimar Publics/ Weimar Subjects. Rethinking the Political Culture of Germany in the 1920s (pp. 339-359). New York: Berghahn. Gender and Colonial Politics after the Versailles Treaty Lora Wildenthal In November 1918, the revolutionary government of republican Germany proclaimed the political enfranchisement of women. In June 1919, Article 119 of the Versailles Treaty announced the disenfranchisement of German men and women as colonizers. These were tremendous changes for German women and for the colonialist movement. Yet colonialist women's activism changed surprisingly little, and the Weimar Republic proved to be a time of vitality for the colonialist movement. The specific manner in which German decolonization took place profoundly shaped interwar colonialist activism. It took place at the hands of other colonial powers and at the end of the first "total" war. The fact that other imperial metropoles forced Germany to relinquish its colonies, and not colonial subjects (many of whom had tried and failed to drive Germans from their lands in previous years), meant that German colonialists focused their criticisms on those powers. When German colonialists demanded that the Versailles Treaty be revised so that they could once again rule over Africans and others, they were expressing not only a racist claim to rule over supposed inferiors but also a reproach to the Entente powers for betraying fellow white colonizers. The specific German experience of decolonization affected how Germans viewed their former colonial subjects. In other cases of decolonization, bitter wars of national liberation dismantled fantasies of affection between colonizer and colonized. -

Northumbria Research Link

Northumbria Research Link Citation: Hellawell, Sarah (2018) Antimilitarism, Citizenship and Motherhood : the formation and early years of the Women’s International League (WIL), 1915–1919. Women's History Review, 27 (4). pp. 551-564. ISSN 0961-2025 Published by: UNSPECIFIED URL: This version was downloaded from Northumbria Research Link: http://northumbria-test.eprints- hosting.org/id/eprint/49784/ Northumbria University has developed Northumbria Research Link (NRL) to enable users to access the University’s research output. Copyright © and moral rights for items on NRL are retained by the individual author(s) and/or other copyright owners. Single copies of full items can be reproduced, displayed or performed, and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided the authors, title and full bibliographic details are given, as well as a hyperlink and/or URL to the original metadata page. The content must not be changed in any way. Full items must not be sold commercially in any format or medium without formal permission of the copyright holder. The full policy is available online: http://nrl.northumbria.ac.uk/pol i cies.html This document may differ from the final, published version of the research and has been made available online in accordance with publisher policies. To read and/or cite from the published version of the research, please visit the publisher’s website (a subscription may be required.) Sarah Hellawell Antimilitarism, Citizenship and Motherhood Antimilitarism, Citizenship and Motherhood: the formation and early years of the Women’s International League (WIL), 1915 – 1919 Abstract This article examines the concept of motherhood and peace in the British women’s movement during the Great War. -

Split Infinities: German Feminisms and the Generational Project Birgit

This is an Accepted Manuscript of an article published by Taylor & Francis in Oxford German Studies on 15 April 2016, available online: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00787191.2015.1128648 Split Infinities: German Feminisms and the Generational Project Birgit Mikus, University of Oxford Emily Spiers, St Andrews University When, in the middle of the nineteenth century, the German women’s movement took off, female activists/writers expressed a desire for their political work to initiate a generational project. The achievement of equal democratic rights for men and women was perceived to be a process in which the ‘democratic spirit’ was instilled in future generations through education and the provision of exceptional role models. The First Wave of the women’s movement laid the ground, through their writing, campaigning, and petitioning, for the eventual success of obtaining women’s suffrage and sending female, elected representatives to the Reichstag in 1919. My part of this article, drawing on the essays by Hedwig Dohm (1831–1919) analyses how the idea of women’s political and social emancipation is phrased in the rhetoric of a generational project which will, in the short term, bring only minor changes to the status quo but which will enable future generations to build on the foundations of the (heterogeneous, but mostly bourgeoisie-based) first organised German women’s movement, and which was intended to function as a generational repository of women’s intellectual history. When, in the mid-2000s, a number of pop-feminist essayistic volumes appeared in Germany, their authors expressed the desire to reinvigorate feminism for a new generation of young women. -

Living War, Thinking Peace (1914-1924)

Living War, Thinking Peace (1914-1924) Living War, Thinking Peace (1914-1924): Women’s Experiences, Feminist Thought, and International Relations Edited by Bruna Bianchi and Geraldine Ludbrook Living War, Thinking Peace (1914-1924): Women’s Experiences, Feminist Thought, and International Relations Edited by Bruna Bianchi and Geraldine Ludbrook This book first published 2016 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2016 by Bruna Bianchi, Geraldine Ludbrook and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-8684-X ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-8684-0 CONTENTS Introduction .............................................................................................. viii Bruna Bianchi and Geraldine Ludbrook Part One: Living War. Women’s Experiences during the War Chapter One ................................................................................................. 2 Women in Popular Demonstrations against the War in Italy Giovanna Procacci Chapter Two .............................................................................................. 26 Inside the Storm: The Experiences of Women during the Austro-German Occupation -

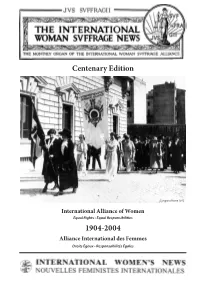

IAW Centenary Edition 1904-2004

Centenary Edition Congress Rome 1923 International Alliance of Women Equal Rights - Equal Responsibilities 1904-2004 Alliance International des Femmes Droits Égaux - Responsabilités Égales Centenary Edition: Our Name 1904-1926 First Constitution adopted in Berlin, Germany, June 2 & 4, 1904 Article 1 - Name: The Name of this organization shall be the International Woman Suffrage Alliance (IWSA) Alliance Internationale pour le suffrage des Femmes Weltbund für Frauen-stimmrecht 1926-1949 Constitution adopted in Paris, 1926 Article 1 - Name: The name of the federation shall be the International Alliance of Women for Suffrage and Equal Citizenship (IAWSEC) Alliance Internationale pour le suffrage des Femmes et pour l’Action civique et politique des Femmes 1949-2004 The third Constitution adopted in Amsterdam, 1949 Article 1 - Name: The name of the federation shall be the International Alliance of Women, Equal Rights - Equal Responsibilities (IAW) L’Alliance Internationale des Femmes, Droits Egaux - Responsabilités Égales (AIF) Centenary Edition:Author Foreword Foreword My personal introduction to the International Alliance somehow lost track of my copy of that precious document. of Women happened in dramatic circumstances. Having Language and other difficulties were overcome as we been active in the women’s movement, I was one of those scrounged typewriters, typing and carbon paper, and were fortunate to be included in the Australian non-government able to distribute to all of the United Nations delegations delegation to Mexico City in 1975. our -

Chrystal Macmillan from Edinburgh Woman to Global Citizen

Chrystal Macmillan From Edinburgh Woman to Global Citizen di Helen Kay * Abstract : What inspired a rich well-educated Edinburgh woman to become a suffragist and peace activist? This paper explores the connection between feminism and pacifism through the private and published writings of Chrystal Macmillan during the first half of the 20 th century. Throughout her life, Chrystal Macmillan was conscious of a necessary connection between the gendered nature of the struggle for full citizenship and women’s work for the peaceful resolution of international disputes. In 1915, during World War One, she joined a small group of women to organise an International Congress of Women at The Hague to talk about the sufferings caused by war, to analyse the causes of war and to suggest how war could be avoided in future. Drawing on the archives of women’s international organisations, the article assesses the implications and relevance of her work for women today. Do we know what inspired a rich well-educated Edinburgh woman to become a suffragist and peace activist in the early part of the 20 th century? Miss Chrystal Macmillan was a passionate campaigner for women’s suffrage, initially in her native land of Scotland but gradually her work reached out to women at European and international levels. She wrote, she campaigned, she took part in public debates, she lobbied, she organised conferences in Great Britain and in Europe: in all, she spent her life working for political and economic liberty for women. In all her work and writing, she was opposed to the use of force and was committed, almost to the point of obsession, to pursuing the legal means to achieve political ends. -

Feminism Under Fascism

Feminism under Fascism In Germany of the 1930s Ruchira Gupta1 In speech after speech, the Nazis promised the restoration of the father’s authority and the mother’s responsibility within the family to Kinder, Küche, Kirche (Children, Kitchen and the Church). German families had become much smaller, married women had gained the legal right to keep their own salaries, and both married and single women were joining the paid-labour force in record numbers. Women’s dress and hair were both becoming shorter. Thirty-two women deputies were elected to the Reichstag (more than in the USA and UK at the time). Radical feminists had begun to organize against the protective legislation that kept women out of many jobs, and to work toward such international goals as demilitarization and pacifism. Many believed that reinforcing the traditional roles of women and men in the family “would provide stability in a social world that seemed to be rapidly slipping from their control.” The Nazi Party gained rapid support among those social groups and classes where women had made the most headway in the I920s, and where there was, in consequence, a measure of sexual competition for jobs during the depression. Nazi propaganda attacks on the ‘degeneracy’ of childless, educated, decorative city women who smoked and drank, struck some deep chords among humiliated and anxious German men preoccupied with their perceived loss of masculinity. These men felt they could only regain their masculinity through militarism and emphasis on racial superiority. The purity of the blood, the numerical power of the German race, and the sexual vigour of its men thus became ideological Nazi goals: Its militarism was predicated upon overt male supremacy and its racialist ideology could only succeed by controlling women’s procreative role. -

How WILPF Started

Women's International League for Peace and Freedom (WILPF) How did it start in 1915? Women campaigners from Europe and America had been meeting together under the auspices of The International Women’s Suffrage Association (IWSA) since the start of the 20th Century. Most came to these international meetings as delegates from their national suffrage associations. As they worked together at the international level to exchange ideas and build campaigns for obtaining the franchise in their respective countries, they also began to discuss other issues of concern to women. And by 1910, this group formed a well-organised, vibrant international network. The IWSA congress in Budapest in 1913 attracted 2800 participants from all over Europe and America: the international delegates numbered about 500. The author Charlotte Perkins Gilman attended the event and afterwards wrote about the new awakening of cooperation between women. ‘The most amazing thing in these great International Women’s Congresses is the massing and moving of the hitherto isolated and stationary sex.’ ’ [Jus Suffragii 15 July 1913, p6] Women were united not only by the desire to gain the vote but a passionate desire to improve the situation for all women and men, but particularly the situation of exploited women. ‘It was not merely a dry discussion of ways and means to get the vote, but comprehensive studies of social and moral conditions, and of how women could better them. At almost every session one learned of the White Slave Traffic; of ways to protect young girls; of efforts of women legislators to raise the age of consent; of State insurance for mothers; of solutions of the problem of the illegitimate child; of better laws for working women; of the abolition of sweat shops and child labour.’ [Jus Suffragii 15 July 1913, p6] All over Europe, women were joining together at a national level to campaign on issues that affected them. -

Feminist Pacifism

Version 1.0 | Last updated 10 November 2015 Feminist Pacifism By Annika Wilmers A minority section of the women’s movements opposed World War I and organized the International Congress of Women at The Hague in April 1915. Its participants demanded women’s rights and more democracy in politics as a precondition for peace. Congress members founded the International Committee of Women for Permanent Peace, which became the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom in 1919. Table of Contents 1 The First Months of War 2 Organizing against the War and the International Congress of Women at The Hague 3 The International Committee of Women for Permanent Peace and its Work for Mediation 4 Feminist Pacifism between International Networking and Wartime Barriers 5 The ICWPP and the Peace Conference Selected Bibliography Citation The First Months of War Feminist pacifism can be traced back to the 19th century, but compared to other relevant topics of the time, like women’s work or suffrage, pacifism was not a main priority of the women’s movements before World War I, and interest in pacifism varied from country to country. Before 1914, women were already playing an active part within the peace movements, but feminist pacifism as an individual branch of the international women’s movement only came to life when a minority faction of the women’s movements opposed World War I. After the outbreak of World War I, the vast majority of women’s movements in the warring countries supported the war efforts of their home countries, but feminist opposition to the war can be found from August 1914 on. -

Spring 2016 Recounting the Past a Student Journal of Historical Studies

Recounting the Past A Student Journal of Historical Studies Department of History At Illinois State University Number 17 • Spring 2016 Recounting the Past A Student Journal of Historical Studies Department of History At Illinois State University Number 17 • Spring 20152016 Editors Issam Nassar Richard Soderlund Graduate Assistant Lacey Brown Editorial Board Kyle Ciani Alan Lessoff Sudipa Topdar Christine Varga-Harris Amy Wood Recounting the Past highlights scholarship from graduate and undergraduate students in the core courses for the History program. These courses teach students how to find, access and critically assess primary sources as well as how to integrate the scholarship of experts in the field into their research. The papers in this issue highlight important theoretical insights and thematic streams in the discipline of history. Recounting the Past A Student Journal of Historical Studies TABLE OF CONTENTS Nora Dunne 1 Fighting for Their Reproductive Rights: Latina Women and Forced Sterilization in the 1970s Meghan Hawkins 15 Conquest, Colonialism and the Creation of the Irish Other Kayla Iammarino 37 “Colonization of the Mind” in Knowledge, Race, and Nationalism Taylor Long 45 What Killed Greenwich Village?: The Dilemma That Comes From Pronouncing Any Creative Center “Dead” Lucas Mays 60 The Delaware Whipping Post: Ancient Punishments in an Enlightened Age Chris Moberg 73 A Vision of Peace: The International Congress of Women at The Hague Chris Roberts 92 Real Victims and Bad Memories: The Sabra & Shatila Massacre and Modern Israeli Memory Zohra Saulat 108 Subjects of the Empire and Subject to the Empire: Gender, Power, and The Inconceivable “Victims” of the British Raj (1858-1947) Greg Staggs 117 Edward Coles and the Fight to Defeat Slavery in Illinois Fighting For Their Reproductive Rights: Latina Women and Forced Sterilization in the 1970s By Nora Dunne Dolores Madrigal gave birth on October 12, 1973.