Achieving Educational Excellence: the Challenge of the 90'S in the Federated States of Micronesia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nineteenth Congress of the Federated States of Micronesia

NINETEENTH CONGRESS OF THE FEDERATED STATES OF MICRONESIA SECOND SPECIAL SESSION, 2015 C.B. No. 19-56 A BILL FOR AN ACT To amend Public Law No. 19-10, by amending sections 3, 4, 5 and 6 thereof, to change the use and allottee of funds previously appropriated therein for the purpose of funding public projects and social programs in the State of Pohnpei and Chuuk, to offer technical amendments, and for other purposes. BE IT ENACTED BY THE CONGRESS OF THE FEDERATED STATES OF MICRONESIA: 1 Section 1. Section 3 of Public Law No. 19-10 is hereby 2 amended to read as follows: 3 “Section 3. Of the sum of $2,100,000 appropriated by 4 this act, [$300,000] $400,000 is apportioned for 5 public projects and social programs in the State of 6 Kosrae. 7 State of Kosrae ........................... $ 400,000 8 (a) COM-Poultry Pilot Project ...... 20,000 9 (b) Ditch improvement 10 (Srem to Infala, Malem) ..................... 2,000 11 (c) Outreach Program ............... 30,000 12 (d) B.A. program ................... 40,000 13 (e) Kosrae High School Lunch Program 40,000 14 (f) Contractual Service for 15 special assistant and office trainees ....... 10,000 16 (g) Malem multi purpose building ... 20,000 17 (h) Utwe multi purpose building .... 20,000 CBL 19-62 C.B. No. 19-56 1 (i) Contributions to State, Municipal 2 and social activities, programs and events . $ 10,000 3 (j) Contractual Service 4 (Security guards) ........................... 5,000 5 (k) Reimbursement obligation to Kosrae 6 Junior Tennis [travel needs] Program ........ 3,000 7 (l) Road improvement projects ..... -

A Community Approach to Introducing Young Children to Early Mathematics: a Study of Kosraean Preschool Children in Their Homes

A COMMUNITY APPROACH TO INTRODUCING YOUNG CHILDREN TO EARLY MATHEMATICS: A STUDY OF KOSRAEAN PRESCHOOL CHILDREN IN THEIR HOMES A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN EDUCATION DECEMBER 2014 By Tulensru Waguk Dissertation Committee: Neil Pateman, Chairperson Sandy Dawson Betsy Brenner Tom Craven Jerry Lipka ABSTRACT This study seeks to determine the impact of parents at home on the development of mathematical concepts among young children of preschool age. This study also looks into the influences of other members of the family, relatives, and the community in the mathematics development of the child-research participant. It focuses on the influences of parents and other members of the family to their children’s mathematics learning at home or in the community The study seeks to answer the following questions: 1. How do parents influence preschool children’s mathematics learning? 2. How do other members of the family and people in the community contribute to the mathematics development of preschool children? To seek answers to these questions, case studies of families were developed from focus group meetings, interviews with parents, observations of children at their homes, and parents’ diaries of children activities, which were kept in the home. Findings suggest that the various environments; although they are all island environments, differently influence both the development of mathematical language and the range of mathematics activities in the homes and community in which each child lives. The nuclear family influences, the extended family influences, and neighbors’ influences contributed to the mathematics development of each child. -

Infrastructure Development Plan (IDP)

Federated States of Micronesia INFRASTRUCTURE DEVELOPMENT PLAN FY2004-FY2023 Prepared by: DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION, COMMUNICATIONS & INFRASTRUCTURE MAY 2004 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .......................................................................................................v 1. Introduction..............................................................................................................1 2. Preparation of Infrastructure Development Plan .....................................................2 2.1 Historical Background...................................................................................... 2 2.2 Preparation of Draft Final Report.................................................................... 2 2.3 Final IDP Report .............................................................................................. 3 2.4 Formal Submission of the IDP.......................................................................... 3 2.5 Preparation of Final IDP Document ................................................................ 3 3. Planning Context......................................................................................................4 3.1 FSM Planning Framework ............................................................................... 4 3.2 Public Sector Investment Program ................................................................... 4 3.3 Public and Private Sector Management of Infrastructure................................ 5 3.4 National Government Infrastructure Priorities............................................... -

GAO-07-514R Compacts of Free Association

United States Government Accountability Office Washington, DC 20548 May 25, 2007 Congressional Committees Subject: Compacts of Free Association: Micronesia’s and the Marshall Islands’ Use of Sector Grants Supplementing our December 2006 report entitled Compacts of Free Association: Micronesia and the Marshall Islands Face Challenges in Planning for Sustainability, Measuring Progress, and Ensuring Accountability,1 this report provides information on the uses of economic assistance provided under the amended U.S. compacts with the Federated States of Micronesia (FSM) and the Republic of the Marshall Islands (RMI) from 2004 through 2006. From 1987 through 2003,2 the United States provided $2.1 billion in economic assistance to the FSM3 and the RMI through a Compact of Free Association. In 2003, the U.S. government approved amended compacts with the FSM and the RMI,4 providing a combined total of $3.6 billion for the two countries in 2004 through 2023.5 The amended compacts identify the 20 years of grant assistance as intended to assist the FSM and RMI governments in promoting the economic advancement and budgetary self-reliance of their people. Under the amended compacts, U.S. grant funding decreases annually,6 paired with increasing contributions to trust funds for the FSM and the RMI; earnings from the trust funds are intended to provide a source of revenue when the grants expire in 2023. In addition, the annual grant funding is 1 GAO, Compacts of Free Association: Micronesia and the Marshall Islands Face Challenges in Planning for Sustainability, Measuring Progress, and Ensuring Accountability, GAO-07-163 (Washington, D.C.: Dec. -

Taking Responsibility for Our Schools: a Series of Four Articles on Education in Micronesia. INSTITUTION Pacific Resources for Education and Learning, Honolulu, HI

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 467 541 RC 023 666 AUTHOR Hezel, Francis X. TITLE Taking Responsibility for Our Schools: A Series of Four Articles on Education in Micronesia. INSTITUTION Pacific Resources for Education and Learning, Honolulu, HI. Region XV Comprehensive Assistance Center. SPONS AGENCY Department of Education, Washington, DC. PUB DATE 2002-06-00 NOTE 49p.; Introduction by Hilda C. Heine. CONTRACT S283A950001 PUB TYPE Opinion Papers (120) Reports Descriptive (141) EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF01/PCO2 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Academic Achievement; Brain Drain; Community Involvement; Education Work Relationship; Educational Change; *Educational Objectives; Elementary Secondary Education; Foreign Countries; *Pacific Islanders; Parent Participation; *Role of Education; *School Community Relationship; School Culture; *School Effectiveness IDENTIFIERS Exemplary Schools; *Federated States of Micronesia; Marshall Islands; Palau ABSTRACT Mobilizing communities to support educational improvements is one of the challenges confronting educators in the Freely Associated States (FAS), which consists of the Federated States of Micronesia, the Republic of the Marshall Islands, and the Republic of Palau. This booklet aims to establish a consensus on broad educational goals and to rebuild the sense of community ownership of schools that is missing today. "What Should Our Schools Be Doing?" describes conflicting views about whether education should provide for manpower training, cultural preservation, or academic skills, given the current poor academic achievement in the FAS and high rates of emigration to find work. It is suggested that a new education system can accommodate all three visions. "How Good Are Our Schools?" attempts to show the current status of schooling in each country but is hampered by incomplete data. Although test scores are the only data consistently available, there are other measures for school success. -

2018 Kosrae Monitoring Report FINAL 2 12 18.Pdf

Federated States of Micronesia Department of Education Division of Special Services Kosrae State Special Education Program Annual Verification Monitoring Report January 15-19, 2018 Introduction The Federated States of Micronesia (FSM) National Department of Education (NDOE) receives funding under Part B the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) through the U.S. Department of Education. This funding is designed to supplement the provision of special education and related services for eligible children with disabilities within each State of the FSM. In addition, the funds are being used to improve and expand programs and services for children with disabilities in the four states. The special education and related services implemented by use of the IDEA funds are consistent with the approved FSM Special Education Handbook (2012) and FSM P.L. 14-08. Under the requirements of IDEA, the FSM Government has assured the grantor that all children with disabilities will receive a Free Appropriate Public Education (FAPE) consistent with the requirements of IDEA. The FSM Special Education Program, operated through the Department of Education, contains specific requirements and provisions for funding special education program within each State. In receiving funding under IDEA, each state must assure that the provisions of Public Law 14-08 and the requirements of IDEA, Part B are being fulfilled. Additionally, to be eligible for IDEA funding, each State must annually submit a Special Education LEA Application that includes specific Assurances for the delivery of special education and related services, a Local Performance Plan (LPP) and a detailed budget for the coming school year. Under the General Supervision requirements of IDEA, the FSM National Department of Education (NDOE) implements a comprehensive Special Education Monitoring program to ensure compliance in each FSM State with IDEA and to provide student performance data that will assist in making determinations for each state. -

Libraries, Archives and Museums: What's in Them for Us? PIALA '98

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 433 031 IR 057 416 AUTHOR Cohen, Arlene, Ed. TITLE Libraries, Archives and Museums: What's in Them for Us? PIALA '98. Selected Papers from the Pacific Islands Association of Libraries and Archives Conference (8th, Tofol, Kosrae, Federated States of Micronesia, November 17-20, 1998). INSTITUTION Pacific Islands Association of Libraries and Archives, Guam. ISBN ISBN-1-892485-05-2 PUB DATE 1999-00-00 NOTE 86p.; For the 1997 proceedings, see ED 422 011. AVAILABLE FROM University of Guam, RFK Library, UOG Station, Mangilao, Guam 96923 ($25). PUB TYPE Collected Works - Proceedings (021) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC04 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Archives; Conferences; Cooperative Programs; Curriculum Development; Elementary Secondary Education; Foreign Countries; *Libraries; Library Associations; Library Collection Development; *Library Development; *Library Services; Museums; Postsecondary Education; Preservation; Program Development IDENTIFIERS Federated States of Micronesia; Hawaii; Library Materials Conservation; *Pacific Islands; Peace Corps ABSTRACT This proceedings contains papers from the 1998 annual conference of the Pacific Islands Association of Libraries and Archives (PIALA). After welcoming remarks from Henry Robert and Isabel Rungrad, the following papers are included: "Sharing Our Successes, Discussing Our Future: A Survey of Pacific Collections Activities--Report from the University of Hawaii's Conference" (Karen M. Peacock); "Curriculum Development and the Preservation of Kosraean Language and Culture" (Alister Tolenoa); "Peace Corps Micronesia: 'The Library Development & Reading Education Project'" (Jeff Henry, Lee Allison, Rose Rojas, and Kani Le); "The Hawaii Library Association and PIALA: A Pacific Partnership" (Ruth Horie); "How Can Tourism Support and Archive Conservation in Kosrae?" (Justus Alokoa); "Status of Conservation in Kosrae" (Simson Abraham); "'Strengthening Academic Programs': The College of Micronesia-FSM Title III Project" (Jean Thoulag); "Daniel Peacock and the Foundation for Micronesia's Libraries" (Nicholas J. -

COMET Spring 2019 High School Report

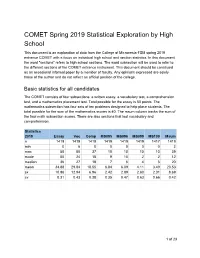

COMET Spring 2019 Statistical Exploration by High School This document is an exploration of data from the College of Micronesia-FSM spring 2019 entrance COMET with a focus on individual high school and section statistics. In this document the word "sections" refers to high school sections. The word subsection will be used to refer to the different sections of the COMET entrance instrument. This document should be construed as an occasional informal paper by a member of faculty. Any opinions expressed are solely those of the author and do not reflect an official position of the college. Basic statistics for all candidates The COMET consists of four subsections: a written essay, a vocabulary test, a comprehension test, and a mathematics placement test. Total possible for the essay is 50 points. The mathematics subsection has four sets of ten problems designed to help place students. The total possible for the sum of the mathematics scores is 40. The msum column tracks the sum of the four math subsection scores. There are also sections that test vocabulary and comprehension. Statistics 2019 Essay Voc Comp MS095 MS096 MS099 MS100 Msum n 1419 1419 1419 1419 1419 1419 1417 1419 min 0 6 0 0 0 0 0 3 max 50 80 37 10 10 10 10 39 mode 50 24 18 9 10 2 2 12 median 36 27 18 7 6 4 3 20 mean 34.88 29.84 18.55 6.84 6.09 4.11 3.49 20.53 sx 10.86 12.94 6.96 2.42 2.89 2.60 2.31 8.69 cv 0.31 0.43 0.38 0.35 0.47 0.63 0.66 0.42 1 of 23 Correlations internal to the data To provide context for the correlations between the subsections of the COMET, the spring 2018 was: Correl Essay Voc Comp MS095 MS096 MS099 MS100 msum Essay 1.00 0.57 0.65 0.53 0.57 0.50 0.38 0.58 Vocab 0.57 1.00 0.73 0.46 0.58 0.55 0.49 0.61 Comp 0.65 0.73 1.00 0.50 0.59 0.56 0.40 0.60 Msum 0.58 0.61 0.60 0.82 0.90 0.89 0.81 1.00 This pattern of relationships shifted this year. -

FOURTH REGULAR SESSION TWENTIETH CONGRESS Federated States of Micronesia

JOURNAL FOURTH REGULAR SESSION TWENTIETH CONGRESS of the Federated States of Micronesia PALIKIR, POHNPEI August 2015 PALIKIR, POHNPEI Convened on Friday, 11th of May 2018 Adjourned on Monday, 28th of May 2018 JOURNAL FOURTH REGULAR SESSION TWENTIETH CONGRESS OF THE FEDERATED STATES OF MICRONESIA July 2018 PALIKIR, POHNPEI Convened on Friday, 11th, of May 2018 Adjourned on Monday, 28th of May 2018 Compiled by the Office of the Speaker And Printed by Good News Press – Kolonia, Pohnpei Twentieth Congress of the Federated States of Micronesia FOURTH REGULAR SESSION May 11th, 2018 thru May 28th, 2018 TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION No. Page CERTIFICATION …………………… IV ORGANIZATION Leadership and Membership …………………… V Standing Committees …………………… VI Congressional Offices …………………… VII SUMMARY OF LEGISLATION …………………… VIII-XII DAILY JOURNAL INDEX …………………… XIII-XIV DAILY JOURNAL …………………… 1-172 STANDING COMMITTEE REPORTS …………………… 173-218 SPECIAL COMMITTEE REPORTS ............................... 219-221 COMMUNICATIONS Presidential Communications …………………… 222-227 FSM Supreme Court Communications …………………… 228-229 Member Communications …………………… 230-232 Departmental Communications …………………… 233-234 Agencies and Governmental Authorities …………………… 235-236 State Communications …………………… 237-238 State Supreme Court Communications …………………… 239-240 Municipal or Town Communications …………………… 241-242 Foreign Government Communications …………………… 243-245 Miscellaneous Communications …………………… 246-247 PRESIDENTIAL VETO MESSAGE …………………… 248-249 CONSTITUTION OF THE FEDERATED STATES -

NMCT Math Trend 35% 33% 30% 30% 29% 27% 25% 25% 20% 15% 10% 5% 0% 2014-2015 2016-2017 2017-2018

1 | P a g e Contents Background......................................................................................................................... 3 Student Assessment .......................................................................................................... 3 Exams Results for Nation-wide Performance by Benchmarks .................................. 3 Exam Results for Recent Years by Standards .............................................................. 3 Exams Results Comparing States ................................................................................. 3 Sixth Grade Reading Results ......................................................................................... 4 Eighth Grade Reading Results ....................................................................................... 4 Tenth Grade Reading Results ........................................................................................ 5 Sixth Grade Math Results .............................................................................................. 6 Tenth Grade Math Results ............................................................................................. 8 List of Figures Figure 1: Grade 6 Reading Benchmarks – meeting or exceeding ................................. 4 Figure 2: Grade 8 – Reading Benchmarks – meeting or exceeding ............................... 5 Figure 3: Grade 10 -Reading Benchmarks – meeting or exceeding .............................. 5 Figure 4: Grade 4 Math benchmarks – meeting or exceeding -

FSM Information Services

FSM Information Services Press Release FSM & KSA COVID-19 Task Forces Complete Additional Simulation Exercises, Contact Tracing, & Community Workshops; “I think you can open soon, and it will be your decision when,” Secretary Taulung Says TOFOL, Kosrae—From July 18th to 22nd, 2020, the Federated States of Micronesia’s (FSM’s) COVID-19 Task Force extended its stay in the State of Kosrae, per the Government’s request, to assist in additional readiness and simulation exercises to help prepare the State for the repatriation of its residents. Amongst the tasks completed included contact tracing workshops, community empowerment exercises, and several simulation exercises. This release will primarily relay the updated strengths and weaknesses discussed in the July 22nd debriefing for the State’s Point of Entry, Quarantine, and Isolation sites. Citizens only interested in knowing when Kosrae will reopen for repatriating its residents are advised that, although the date is still unknown, significant progress has been made towards improving the State’s capacity. “I think you can open soon, and it will be your decision when,” the Honorable Livingston A. Taulung, Secretary of the Department of Health & Social Affairs, said in the Task Force’s debriefing to the Honorable Carson K. Sigrah, Governor of the State of Kosrae. “Many of the biggest gaps identified last week have either been addressed or are actively being addressed by your team.” The Point of Entry has seen “a lot of improvements,” said Mr. Ben Jackson Amor. “Prior to the screening, the queuing passengers would wash their hands before going to the screening area. Along with that, the signage posted in the screening area is a big plus.” The traffic cones previously used to designate social distancing markers have been replaced with colored tape, ensuring that social distancing is maintained regardless of any troublesome weather. -

Achieving Educational Excellence: the Challenge of the 90S in the Federated States of Micronesia

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 325 907 EA 022 302 AUTHOR Drier, Harry N.; Grossman, Gary M. TITLE Achieving Educational Excellence: The Challenge of the 90s in the Federated States of Micronesia. Overview of National Findings and Recommendations- INSTITUTION Ohio State Univ., Columbus. Center on Education and Training for Employment. SPONS AGENCY Micronesia Dept. of Human Resources, Palikir, Pohnpei. Office of Education. PUB DATE Jan 90 CONTRACT FSM-45 NOTE 71p.; For the final report, see EA 022 303. PUB TYPE Reports - Research/Technical (143) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC03 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Curriculum Development; Demography; *Educational Assessment; Educational Equity (Finance); Educational Facilities; Educational Finance; *Educational Improvement; *Educational Objectives; *Educational Quality; Elementary Secondary Education; Equal Education; Excellence in Education; Foreign Countries; Governance; Population Distribution; *School Effectiveness; Teacher Effectiveness IDENTIFIERS *Micronesia ABSTRACT The educational system of the Federated States of Micronesia (FSM) is reviewed with a focus on efficiency, accessibility, and effectiveness. Methodology is based on individual and group interviews and informal discussions with approximately 1,500 respondents from all sectors of the educational community, and on observation of over 75 elementary and secondary schoolfacilities. and 5 postsecondary campuses. Five key issues for reform are examined: infrastructure; personnel; curriculum; governance/policy; and finance. Recommendations are made for improvement