Asian Longhorned Beetle Response Guidelines

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Detecting Signs and Symptoms of Asian Longhorned Beetle Injury

DETECTING SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS OF ASIAN LONGHORNED BEETLE INJURY TRAINING GUIDE Detecting Signs and Symptoms of Asian Longhorned Beetle Injury TRAINING GUIDE Jozef Ric1, Peter de Groot2, Ben Gasman3, Mary Orr3, Jason Doyle1, Michael T Smith4, Louise Dumouchel3, Taylor Scarr5, Jean J Turgeon2 1 Toronto Parks, Forestry and Recreation 2 Natural Resources Canada - Canadian Forest Service 3 Canadian Food Inspection Agency 4 United States Department of Agriculture - Agricultural Research Service 5 Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources We dedicate this guide to our spouses and children for their support while we were chasing this beetle. Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Detecting Signs and Symptoms of Asian Longhorned Beetle Injury : Training / Jozef Ric, Peter de Groot, Ben Gasman, Mary Orr, Jason Doyle, Michael T Smith, Louise Dumouchel, Taylor Scarr and Jean J Turgeon © Her Majesty in Right of Canada, 2006 ISBN 0-662-43426-9 Cat. No. Fo124-7/2006E 1. Asian longhorned beetle. 2. Trees- -Diseases and pests- -Identification. I. Ric, Jozef II. Great Lakes Forestry Centre QL596.C4D47 2006 634.9’67648 C2006-980139-8 Cover: Asian longhorned beetle (Anoplophora glabripennis) adult. Photography by William D Biggs Additional copies of this publication are available from: Publication Office Plant Health Division Natural Resources Canada Canadian Forest Service Canadian Food Inspection Agency Great Lakes Forestry Centre Floor 3, Room 3201 E 1219 Queen Street East 59 Camelot Drive Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario Ottawa, Ontario CANADA P6A 2E5 CANADA K1A 0Y9 [email protected] [email protected] Cette publication est aussi disponible en français sous le titre: Détection des signes et symptômes d’attaque par le longicorne étoilé : Guide de formation. -

4 Reproductive Biology of Cerambycids

4 Reproductive Biology of Cerambycids Lawrence M. Hanks University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Urbana, Illinois Qiao Wang Massey University Palmerston North, New Zealand CONTENTS 4.1 Introduction .................................................................................................................................. 133 4.2 Phenology of Adults ..................................................................................................................... 134 4.3 Diet of Adults ............................................................................................................................... 138 4.4 Location of Host Plants and Mates .............................................................................................. 138 4.5 Recognition of Mates ................................................................................................................... 140 4.6 Copulation .................................................................................................................................... 141 4.7 Larval Host Plants, Oviposition Behavior, and Larval Development .......................................... 142 4.8 Mating Strategy ............................................................................................................................ 144 4.9 Conclusion .................................................................................................................................... 148 Acknowledgments ................................................................................................................................. -

Oystershell Scale (Lepidosaphes Ulmi) on Green Ash (Fraxinus Pennsylvanica)

Esther Buck(Senior) Oystershell Scale (Lepidosaphes ulmi) on Green Ash (Fraxinus pennsylvanica) I found a green ash tree (Fraxinus pennsylvanica) outside the law building that was covered with Oystershell Scale, (Lepidosaphes ulmi). Oystershell Scale insects on Green Ash twig Oystershell Scale insects The Green Ash normally has an upright oval growth habit growing up to 50ft tall. The Green Ash that I found was only about 20ft tall. The tree also had some twig and branch dieback. The overall health of the plant was fair, it was on the shorter side and did have some dieback but it looked like it could last for a while longer. The dwarfed growth and dieback of branches and twigs was probably a result of the high infestation of Oystershell Scale (Lepidosaphes ulmi) insect on the branches of the tree. Scale insects feeding on plant sap slowly reduce plant vigor, so I think this sample may have been shorter due to the infestation of Scale insects. As with this tree, heavily infested plants grow poorly and may suffer dieback of twigs and branches. An infested host is occasionally so weakened that it dies. The scale insects resemble a small oyster shell and are usually in clusters all over the bark of branches on trees such as dogwood, elm, hickory, ash, poplar, apple etc. The Oystershell Scale insect has two stages, a crawler stage, which settles after a few days. Then the insect develops a scale which is like an outer shell, which is usually what you will see on an infested host. The scales are white in color at first but become brown with maturity. -

Asian Long-Horned Beetle Anoplophora Glabripennis

MSU’s invasive species factsheets Asian long-horned beetle Anoplophora glabripennis The Asian long-horned beetle is an exotic wood-boring insect that attacks various broadleaf trees and shrubs. The beetle has been detected in a few urban areas of the United States. In Michigan, food host plants for this insect are abundantly present in urban landscapes, hardwood forests and riparian habitats. This beetle is a concern to lumber, nursery, landscaping and tourism industries. Michigan risk maps for exotic plant pests. Other common name starry sky beetle Systematic position Insecta > Coleoptera > Cerambycidae > Anoplophora glabripennis (Motschulsky) Global distribution Native to East Asia (China and Korea). Outside the native range, the beetle infestation has been found in Austria and Canada (Toronto) and the United States: Illinois (Chicago), New Jersey, New York (Long Island), and Asian long-horned beetle. Massachusetts. Management notes Quarantine status The only effective eradication technique available in This insect is a federally quarantined organism in North America has been to cut and completely destroy the United States (NEPDN 2006). Therefore, detection infested trees (Cavey 2000). must be reported to regulatory authorities and will lead to eradication efforts. Economic and environmental significance Plant hosts to Michigan A wide range of broadleaf trees and shrubs including If the beetle establishes in Michigan, it may lead to maple (Acer spp.), poplar (Populus spp.), willow (Salix undesirable economic consequences such as restricted spp.), mulberry (Morus spp.), plum (Prunus spp.), pear movements and exports of solid wood products via (Pyrus spp.), black locust (Robinia pseudoacacia) and elms quarantine, reduced marketability of lumber, and reduced (Ulmus spp.). -

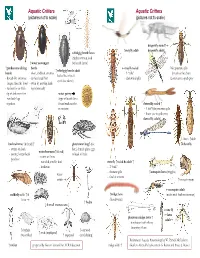

Aquatic Critters Aquatic Critters (Pictures Not to Scale) (Pictures Not to Scale)

Aquatic Critters Aquatic Critters (pictures not to scale) (pictures not to scale) dragonfly naiad↑ ↑ mayfly adult dragonfly adult↓ whirligig beetle larva (fairly common look ↑ water scavenger for beetle larvae) ↑ predaceous diving beetle mayfly naiad No apparent gills ↑ whirligig beetle adult beetle - short, clubbed antenna - 3 “tails” (breathes thru butt) - looks like it has 4 - thread-like antennae - surface head first - abdominal gills Lower jaw to grab prey eyes! (see above) longer than the head - swim by moving hind - surface for air with legs alternately tip of abdomen first water penny -row bklback legs (fbll(type of beetle larva together found under rocks damselfly naiad ↑ in streams - 3 leaf’-like posterior gills - lower jaw to grab prey damselfly adult↓ ←larva ↑adult backswimmer (& head) ↑ giant water bug↑ (toe dobsonfly - swims on back biter) female glues eggs water boatman↑(&head) - pointy, longer beak to back of male - swims on front -predator - rounded, smaller beak stonefly ↑naiad & adult ↑ -herbivore - 2 “tails” - thoracic gills ↑mosquito larva (wiggler) water - find in streams strider ↑mosquito pupa mosquito adult caddisfly adult ↑ & ↑midge larva (males with feather antennae) larva (bloodworm) ↑ hydra ↓ 4 small crustaceans ↓ crane fly ←larva phantom midge larva ↑ adult→ - translucent with silvery bflbuoyancy floats ↑ daphnia ↑ ostracod ↑ scud (amphipod) (water flea) ↑ copepod (seed shrimp) References: Aquatic Entomology by W. Patrick McCafferty ↑ rotifer prepared by Gwen Heistand for ACR Education midge adult ↑ Guide to Microlife by Kenneth G. Rainis and Bruce J. Russel 28 How do Aquatic Critters Get Their Air? Creeks are a lotic (flowing) systems as opposed to lentic (standing, i.e, pond) system. Look for … BREATHING IN AN AQUATIC ENVIRONMENT 1. -

Coleoptera, Cerambycidae, Lamiinae) with Description of a Species with Non‑Retractile Parameres

ARTICLE Two new genera of Desmiphorini (Coleoptera, Cerambycidae, Lamiinae) with description of a species with non‑retractile parameres Francisco Eriberto de Lima Nascimento¹² & Antonio Santos-Silva¹³ ¹ Universidade de São Paulo (USP), Museu de Zoologia (MZUSP). São Paulo, SP, Brasil. ² ORCID: http://orcid.org/0000-0002-5047-8921. E-mail: [email protected] ³ ORCID: http://orcid.org/0000-0001-7128-1418. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract. In this study, two new genera of Desmiphorini (Lamiinae) are proposed: Cleidaria gen. nov., to include Cleidaria cleidae sp. nov. from the state of Chiapas in Mexico, and Obscenoides gen. nov. for Desmiphora (D.) compta Martins & Galileo, 2005. The shape of tarsal claws of Cleidaria cleidae sp. nov. (abruptly narrowed from basal half) is so far, not found in any current genera of the tribe. With respect to Obscenoides compta (Martins & Galileo, 2005) comb. nov., the genitalia of males have an unusual shape with non-retractile parameres. The character combination related to this genital structure is unknown to us in other species in the family, and hypotheses about its function are suggested. Key-Words. Genital morphology; Longhorned beetles; New taxa; Taxonomy. INTRODUCTION the current definitions of some tribes, especially based on the works of Breuning do not take into Lamiinae (Cerambycidae), also known as flat- account adaptive convergences and use superfi- faced longhorns, with more than 21,000 described cial characters to subordinate taxa. species in about 3,000 genera and 87 tribes is Among these tribes, Desmiphorini Thomson, the largest subfamily of Cerambycidae occurring 1860 is not an exception, and its “boundaries” are worldwide (Tavakilian & Chevillotte, 2019). -

Antennal Transcriptome Analysis and Expression Profiles of Olfactory

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Antennal transcriptome analysis and expression profles of olfactory genes in Anoplophora chinensis Received: 13 June 2017 Jingzhen Wang, Ping Hu, Peng Gao, Jing Tao & Youqing Luo Accepted: 27 October 2017 Olfaction in insects is essential for host identifcation, mating and oviposition, in which olfactory Published: xx xx xxxx proteins are responsible for chemical signaling. Here, we determined the transcriptomes of male and female adult antennae of Anoplophora chinensis, the citrus longhorned beetle. Among 59,357 unigenes in the antennal assembly, we identifed 46 odorant-binding proteins, 16 chemosensory proteins (CSPs), 44 odorant receptors, 19 gustatory receptors, 23 ionotropic receptors, and 3 sensory neuron membrane proteins. Among CSPs, AchiCSP10 was predominantly expressed in antennae (compared with legs or maxillary palps), at a signifcantly higher level in males than in females, suggesting that AchiCSP10 has a role in reception of female sex pheromones. Many highly expressed genes encoding CSPs are orthologue genes of A. chinensis and Anoplophora glabripennis. Notably, AchiPBP1 and AchiPBP2 showed 100% and 96% identity with AglaPBP1 and AglaPBP2 from A. glabripennis, with similar expression profles in the two species; PBP2 was highly expressed in male antennae, whereas PBP1 was expressed in all three tissues in both males and females. These results provide a basis for further studies on the molecular chemoreception mechanisms of A. chinensis, and suggest novel targets for control of A. chinensis. Anoplophora chinensis (Forster) (Coleoptera: Cerambycidae), taxonomically regarded as a synonym of Anoplophora malasiaca, is an important worldwide quarantine pest, which is native to East Asia, but which has also been introduced to North America and Europe1,2. -

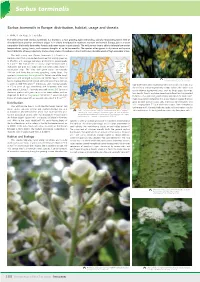

Sorbus Torminalis

Sorbus torminalis Sorbus torminalis in Europe: distribution, habitat, usage and threats E. Welk, D. de Rigo, G. Caudullo The wild service tree (Sorbus torminalis (L.) Crantz) is a fast-growing, light-demanding, clonally resprouting forest tree of disturbed forest patches and forest edges. It is widely distributed in southern, western and central Europe, but is a weak competitor that rarely dominates forests and never occurs in pure stands. The wild service tree is able to tolerate low winter temperatures, spring frosts, and summer droughts of up to two months. The species often grows in dry-warm and sparse forest habitats of low productivity and on steep slopes. It produces a hard and heavy, durable wood of high economic value. The wild service tree (Sorbus torminalis (L.) Crantz) is a medium-sized, fast-growing deciduous tree that usually grows up to 15-25 m with average diameters of 0.6-0.9 m, exceptionally Frequency 1-3 < 25% to 1.4 m . The mature tree is usually single-stemmed with a 25% - 50% distinctive ash-grey and scaly bark that often peels away in 50% - 75% > 75% rectangular strips. The shiny dark green leaves are typically Chorology 10x7 cm and have five to nine spreading, acute lobes. This Native species is monoecious hermaphrodite, flowers are white, insect pollinated, and arranged in corymbs of 20-30 flowers. The tree Yellow and red-brown leaves in autumn. has an average life span of around 100-200 years; the maximum (Copyright Ashley Basil, www.flickr.com: CC-BY) 1-3 is given as 300-400 years . -

Mimosa (Albizia Julibrissin)

W232 Mimosa (Albizia julibrissin) Becky Koepke-Hill, Extension Assistant, Plant Sciences Greg Armel, Assistant Professor, Extension Weed Specialist for Invasive Weeds, Plant Sciences Origin: Mimosa is native to Asia, from Iran to Japan. It was introduced to the United States in 1745 as an ornamental plant. Description: Mimosa is a legume with double-compound leaves that give the 20- to 40-foot tree a fern-like appear- ance. Each leaf has 10 to 25 leaflets and 40 to 60 subleaflets per leaflet. In the summer, the tree pro- duces pink puff flowers. Fruits are produced in the fall and are contained in tan seedpods. The tree often has multiple stems and a broad, spreading canopy. Seed- lings can be confused with other double-compound legumes, but mimosa does not have thorns or prickles like black locust (Robinia pseudoacacia), and has a woody base, unlike hemp sesbania (Sesbania exaltata). Habitat: Mimosa is cold-hardy to USDA hardiness zone 6 and is not found in elevations above 3,000 feet. Mimosa will thrive in full sun in a wide range of soils in any dis- turbed habitat, such as stream banks, roadsides and old fields. Mimosa can live in partial shade, but is almost never found in full shade or dense forests. Mi- mosa often spreads by seeds from nearby ornamental plantings, or by fill dirt containing mimosa seeds. It is a growing problem in aquatic environments, where mimosa gets started on the disturbed stream banks, and its seeds are carried by the running water. Environmental Impact: Mimosa is challenging to remove once it is estab- lished. -

And Lepidoptera Associated with Fraxinus Pennsylvanica Marshall (Oleaceae) in the Red River Valley of Eastern North Dakota

A FAUNAL SURVEY OF COLEOPTERA, HEMIPTERA (HETEROPTERA), AND LEPIDOPTERA ASSOCIATED WITH FRAXINUS PENNSYLVANICA MARSHALL (OLEACEAE) IN THE RED RIVER VALLEY OF EASTERN NORTH DAKOTA A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the North Dakota State University of Agriculture and Applied Science By James Samuel Walker In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE Major Department: Entomology March 2014 Fargo, North Dakota North Dakota State University Graduate School North DakotaTitle State University North DaGkroadtaua Stet Sacteho Uolniversity A FAUNAL SURVEYG rOFad COLEOPTERA,uate School HEMIPTERA (HETEROPTERA), AND LEPIDOPTERA ASSOCIATED WITH Title A FFRAXINUSAUNAL S UPENNSYLVANICARVEY OF COLEO MARSHALLPTERTAitl,e HEM (OLEACEAE)IPTERA (HET INER THEOPTE REDRA), AND LAE FPAIDUONPATLE RSUAR AVSESYO COIFA CTOEDLE WOIPTTHE RFRAA, XHIENMUISP PTENRNAS (YHLEVTAENRICOAP TMEARRAS),H AANLDL RIVER VALLEY OF EASTERN NORTH DAKOTA L(EOPLIDEAOCPTEEAREA) I ANS TSHOEC RIAETDE RDI VWEITRH V FARLALXEIYN UOSF P EEANSNTSEYRLNV ANNOICRAT HM DAARKSHOATALL (OLEACEAE) IN THE RED RIVER VAL LEY OF EASTERN NORTH DAKOTA ByB y By JAMESJAME SSAMUEL SAMUE LWALKER WALKER JAMES SAMUEL WALKER TheThe Su pSupervisoryervisory C oCommitteemmittee c ecertifiesrtifies t hthatat t hthisis ddisquisition isquisition complies complie swith wit hNorth Nor tDakotah Dako ta State State University’s regulations and meets the accepted standards for the degree of The Supervisory Committee certifies that this disquisition complies with North Dakota State University’s regulations and meets the accepted standards for the degree of University’s regulations and meetMASTERs the acce pOFted SCIENCE standards for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE MASTER OF SCIENCE SUPERVISORY COMMITTEE: SUPERVISORY COMMITTEE: SUPERVISORY COMMITTEE: David A. Rider DCoa-CCo-Chairvhiadi rA. -

Recommended Trees to Plant

Recommended Trees to Plant Large Sized Trees (Mature height of more than 45') (* indicates tree form only) Trees in this category require a curb/tree lawn width that measures at least a minimum of 8 feet (area between the stree edge/curb and the sidewalk). Trees should be spaced a minimum of 40 feet apart within the curb/tree lawn. Trees in this category are not compatible with power lines and thus not recommended for planting directly below or near power lines. Norway Maple, Acer platanoides Cleveland Norway Maple, Acer platanoides 'Cleveland' Columnar Norway Maple, Acer Patanoides 'Columnare' Parkway Norway Maple, Acer Platanoides 'Columnarbroad' Superform Norway Maple, Acer platanoides 'Superform' Red Maple, Acer rubrum Bowhall Red Maple, Acer rubrum 'Bowhall' Karpick Red Maple, Acer Rubrum 'Karpick' Northwood Red Maple, Acer rubrum 'Northwood' Red Sunset Red Maple, Acer Rubrum 'Franksred' Sugar Maple, Acer saccharum Commemoration Sugar Maple, Acer saccharum 'Commemoration' Endowment Sugar Maple, Acer saccharum 'Endowment' Green Mountain Sugar Maple, Acer saccharum 'Green Mountain' Majesty Sugar Maple, Acer saccharum 'Majesty' Adirzam Sugar Maple, Acer saccharum 'Adirzam' Armstrong Freeman Maple, Acer x freemanii 'Armstrong' Celzam Freeman Maple, Acer x freemanii 'Celzam' Autumn Blaze Freeman, Acer x freemanii 'Jeffersred' Ruby Red Horsechestnut, Aesculus x carnea 'Briotii' Heritage River Birch, Betula nigra 'Heritage' *Katsura Tree, Cercidiphyllum japonicum *Turkish Filbert/Hazel, Corylus colurna Hardy Rubber Tree, Eucommia ulmoides -

Albizia Zygia Fabaceae

Albizia zygia (DC.) Macbr. Fabaceae - Mimosoideae LOCAL NAMES Igbo (nyie avu); Swahili (nongo); Yoruba (ayin rela) BOTANIC DESCRIPTION Albizia zygia is a deciduous tree 9-30 m tall with a spreading crown and a graceful architectural form. Bole tall and clear, 240 cm in diameter. Bark grey and smooth. Young branchlets densely to very sparsely clothed with minute crisped puberulence, usually soon disappearing but sometimes persistent. Leaves pinnate, pinnae in 2-3 pairs and broadening towards the apex, obliquely rhombic or obovate with the distal pair largest, apex obtuse, 29- 72 by 16-43 mm, leaves are glabrous or nearly so. Flowers subsessile; pedicels and calyx puberulous, white or pink; staminal tube exserted for 10-18 mm beyond corolla. Fruit pod oblong, flat or somewhat transversely plicate, reddish-brown in colour, 10-18 cm by 2-4 cm glabrous or nearly so. The seeds of A. zygia are smaller (7.5-10 mm long and 6.5 to 8.5 mm wide) and flatter than either of the other Albizia, but have the characteristic round shape, with a slightly swollen center. The genus was named after Filippo del Albizzi, a Florentine nobleman who in 1749 introduced A. julibrissin into cultivation. BIOLOGY A hermaphroditic species flowering in January, February, March, August, and September. Fruits ripen in January, February, March, April, November, and December. This tree hybridizes with A. gummifera. Agroforestry Database 4.0 (Orwa et al.2009) Page 1 of 5 Albizia zygia (DC.) Macbr. Fabaceae - Mimosoideae ECOLOGY A light demanding pioneer species, it is rarely found in closed canopy forests dominated by Chlorophora regia and Ficus macrosperma.