THE EYEPIECE POINTER: a USEFUL MICROSCOPE ACCESSORY by C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

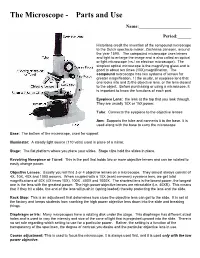

The Microscope Parts And

The Microscope Parts and Use Name:_______________________ Period:______ Historians credit the invention of the compound microscope to the Dutch spectacle maker, Zacharias Janssen, around the year 1590. The compound microscope uses lenses and light to enlarge the image and is also called an optical or light microscope (vs./ an electron microscope). The simplest optical microscope is the magnifying glass and is good to about ten times (10X) magnification. The compound microscope has two systems of lenses for greater magnification, 1) the ocular, or eyepiece lens that one looks into and 2) the objective lens, or the lens closest to the object. Before purchasing or using a microscope, it is important to know the functions of each part. Eyepiece Lens: the lens at the top that you look through. They are usually 10X or 15X power. Tube: Connects the eyepiece to the objective lenses Arm: Supports the tube and connects it to the base. It is used along with the base to carry the microscope Base: The bottom of the microscope, used for support Illuminator: A steady light source (110 volts) used in place of a mirror. Stage: The flat platform where you place your slides. Stage clips hold the slides in place. Revolving Nosepiece or Turret: This is the part that holds two or more objective lenses and can be rotated to easily change power. Objective Lenses: Usually you will find 3 or 4 objective lenses on a microscope. They almost always consist of 4X, 10X, 40X and 100X powers. When coupled with a 10X (most common) eyepiece lens, we get total magnifications of 40X (4X times 10X), 100X , 400X and 1000X. -

How Do the Lenses in a Microscope Work?

Student Name: _____________________________ Date: _________________ How do the lenses in a microscope work? Compound Light Microscope: A compound light microscope uses light to transmit an image to your eye. Compound deals with the microscope having more than one lens. Microscope is the combination of two words; "micro" meaning small and "scope" meaning view. Early microscopes, like Leeuwenhoek's, were called simple because they only had one lens. Simple scopes work like magnifying glasses that you have seen and/or used. These early microscopes had limitations to the amount of magnification no matter how they were constructed. The creation of the compound microscope by the Janssens helped to advance the field of microbiology light years ahead of where it had been only just a few years earlier. The Janssens added a second lens to magnify the image of the primary (or first) lens. Simple light microscopes of the past could magnify an object to 266X as in the case of Leeuwenhoek's microscope. Modern compound light microscopes, under optimal conditions, can magnify an object from 1000X to 2000X (times) the specimens original diameter. "The Compound Light Microscope." The Compound Light Microscope. Web. 16 Feb. 2017. http://www.cas.miamioh.edu/mbi-ws/microscopes/compoundscope.html Text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International (CC BY-NC 4.0) license. - 1 – Student Name: _____________________________ Date: _________________ Now we will describe how a microscope works in somewhat more detail. The first lens of a microscope is the one closest to the object being examined and, for this reason, is called the objective. -

Binocular and Spotting Scope Basics

Binocular and Spotting Scope Basics A good pair of binoculars is a must for most for bird monitoring projects. Certainly, you can observe birds and other wildlife without the aid of binoculars, such as at a feeder, but with them you will see more detail. Binoculars don't have to cost you a lot of money, but should adequately magnify birds for identification. Many 7 x 35 or 8 x 42 power binoculars are affordable and good for bird watching. They should be easy to use and comfortable for you. You can buy binoculars through sporting goods stores, catalogs, and the Internet. How to use binoculars Binoculars are an extension of your eyes. First, use your naked eye to find the birds you are observing. Once you have detected movement and can see the wildlife, use binoculars to see details of a bird’s “field marks.” Everyone’s eyes are different, so before you raise the binoculars, you must calibrate them for your eyes. How to Calibrate Binoculars 1. Binoculars hinge at the center between the two large “barrels,” allowing the eyepieces to fit the width of your eyes (Illustration A). Pivot the hinged barrels so you see a single circle-shaped image, rather than a double-image when looking through them. If the barrels are as close together as they go and you still see two images, you may need to find another pair. The distance between the eyepieces is called the “interpupillary distance.” It is too large if you see two images. The number on the hinge post (angle) will always be the same for your eyes, no matter which binocular you use (A). -

A Guide to Smartphone Astrophotography National Aeronautics and Space Administration

National Aeronautics and Space Administration A Guide to Smartphone Astrophotography National Aeronautics and Space Administration A Guide to Smartphone Astrophotography A Guide to Smartphone Astrophotography Dr. Sten Odenwald NASA Space Science Education Consortium Goddard Space Flight Center Greenbelt, Maryland Cover designs and editing by Abbey Interrante Cover illustrations Front: Aurora (Elizabeth Macdonald), moon (Spencer Collins), star trails (Donald Noor), Orion nebula (Christian Harris), solar eclipse (Christopher Jones), Milky Way (Shun-Chia Yang), satellite streaks (Stanislav Kaniansky),sunspot (Michael Seeboerger-Weichselbaum),sun dogs (Billy Heather). Back: Milky Way (Gabriel Clark) Two front cover designs are provided with this book. To conserve toner, begin document printing with the second cover. This product is supported by NASA under cooperative agreement number NNH15ZDA004C. [1] Table of Contents Introduction.................................................................................................................................................... 5 How to use this book ..................................................................................................................................... 9 1.0 Light Pollution ....................................................................................................................................... 12 2.0 Cameras ................................................................................................................................................ -

Astrophotography Tales of Trial & Error

Astrophotography Tales of Trial & Error Dave & Marie Allen AVAC 13th April 2001 Contents Photos Through Camera Lens magnification Increasing 1 Star trails 2 Piggy back Photos Through the Telescope 3 Prime focus 4 Photo through the eyepiece 5 Eyepiece projection Camera Basics When the photograph is being exposed, Light directed to viewfinder the light is directed onto the film. The viewfinder is completely black. Usual photographic rules apply: Less light ! Longer exposures Higher f number ! Longer exposures Light directed to film Star Motion Stars rise and set – just like the Sun in the daytime. The motion of the stars can cause problems for astrophotography Star Motion Stars rise and set – just like the Sun in the daytime. The motion of the stars can cause problems for astrophotography Star Motion Stars rise and set – just like the Sun in the daytime. The motion of the stars can cause problems for astrophotography Star Motion Stars rise and set – just like the Sun in the daytime. The motion of the stars can cause problems for astrophotography Star Motion Stars rise and set – just like the Sun in the daytime. The motion of the stars can cause problems for astrophotography Tracking the motion of the stars during the exposure is called “guiding”. Requires a polar aligned mount and periodic corrections to keep the subject stationary relative to the camera. Done using slow motion controls – or more often with dual axis correctors. Guiding Photography Technique Guiding Required? Star trails No Piggy back Yes Prime focus Yes Photo through the -

Lab 11: the Compound Microscope

OPTI 202L - Geometrical and Instrumental Optics Lab 8-1 LAB 8: BINOCULARS Prism binoculars are, in reality, a pair of refractive telescopes mounted side by side, one for each of the two eyes. The advantages of binoculars over a single monocular telescope are mainly (1) corrected image orientation and (2) depth perception. Three-dimensional information gathered by using both eyes is also enhanced by the binoculars because of the wide separation of objective lenses (approximately 125 mm) compared with the typical InterPupilary Distance (IPD) of human eyes (approximately 68 mm). Binoculars use either Porro or Roof prisms between the objectives and eyepieces to provide correct image orientation. Porro binoculars are shown in Figure 8.1, with part of the case cut away to show the optical parts. The objectives are cemented achromatic pairs (doublets), or triplets, while the oculars are Kellner or achromatized Ramsden eyepieces. The dotted lines show the path of an axial ray through one pair of Porro prisms. The prisms rotate the image by 180°, so the final image is correct (the image looks the same as the object). The doubling back of the light rays in the Porro prism design has the further advantage of enabling longer focus objectives to be used in short tubes, with consequent high magnification. Figure 8.2 shows Porro prims and Roof prisms. Binoculars have many applications that sometimes have different requirements. Characteristics to take into account are (1) magnification, (2) field of view, (3) light- gathering power, and (4) size and weight. Generally, higher magnification results in narrow fields of view and vice versa. -

Chapter 8 the Telescope

Chapter 8 The Telescope 8.1 Purpose In this lab, you will measure the focal lengths of two lenses and use them to construct a simple telescope which inverts the image like the one developed by Johannes Kepler. Because one lens has a large focal length and the other lens has a small focal length, you will use different methods of determining the focal lengths than was used in ’Optics of Thin Lenses’ lab. 8.2 Introduction 8.2.1 A Brief History of the Early Telescope Although eyeglass-makers had been experimenting with lenses well before 1600, the first mention of a telescope appears in a letter written in 1608 by Hans Lippershey, a Dutch spectacle maker, seeking a patent for a telescope. The patent was denied because of easy telescope duplication and difficulty in patent enforcement. The instrument spread rapidly. Galileo heard of it in the early 1600s and quickly made improvements in lens grinding that increased the magnification from a relatively low value of 2 to as much as 30. With these more powerful telescopes, he observed the Milky Way, the mountains on the Moon, the phases of Venus, and the moons of Jupiter. These early telescopes were a type of ‘opera glass,’ producing erect or ‘right side up’ images but having limited magnification. When Johannes Kepler, a German mathematician and astronomer working in Prague under Tycho Brahe, heard of Galileo’s discoveries, he perfected a different form of telescope. Although Kepler’s design inverts the image, it is much more powerful than the Galilean type. This lab we will use the lenses supplied with the telescope kit. -

Eyepiece Projection

Eyepiece Projection Eyepiece projection is a great way to take detailed shoots of moon and planets. Photographed objects in these images are considerably larger and show more detail than such taken with prime focus shots. Prime focus techniques replace the camera lens with a telescope OTA (no diagonal, no eyepiece), but eyepiece projection adds an eyepiece into the optical path, increasing focal length and magnification considerably. The image below shows the typical eyepiece projection setup. Greater magnification and increased focal length come however at a price. Higher focal length (at the same aperture) results in a higher focal ratio number (1/f). The higher the focal ratio number the fainter the image becomes. This demands longer exposure times or higher ISO speeds to achieve a decent image brightness. Furthermore, constantly moving air layers diffract incoming light. That means, with stronger magnification distortion is magnified as well. The same is true for any mount and telescope shake or vibration. Typical eyepiece projection setup with refractor telescope an DSLR camera. How to do it? The following paragraphs describe equipment that is needed and such which is additionally recommended to make photographer’s life easier. I will share some experiences that I had to learn the hard way; it will help you getting good results sooner. Mount • The mount needs to be strong and sturdy. It has to carry all the weight of telescope, camera and all accessories, furthermore it has to stand steady, even with light breezes. • Many manufacturers are quite “generous” when listing weight capabilities of mounts and tripods in their data sheets. -

Early Observations, from Telescopes to Spacecraft

How Telescopes Work 16.1 You have probably seen a telescope before, and wondered how it works! Telescopes are important in astronomy because they do two things extremely well. Their large lenses and mirrors can collect much more light than the human eye, which make it possible to see very faint things. This is called Light Gathering Ability. They also make distant things look much bigger than what the human eye can see so it is easier to study details. This is called magnification. The human eye at night is a circle about 7 millimeters in diameter, called the pupil, which lets light pass through its lens and onto the retina. A telescope can have a main mirror or lens that can be many meters in diameter. How do you figure out how much Light Gathering Ability a telescope has compared to the human eye? Just calculate the area of the two circles and form their ratio! Problem 1 – The human eye can have a pupil diameter of as much as 7 millimeters. Using the formula for the area of a circle, and a value of π = 3.145, what is the area of the human pupil in square millimeters? Problem 2 - The Hubble Space Telescope mirror has a diameter of 2.4 meters, which equals 2400 millimeters. What is the area of the Hubble mirror in square millimeters? Problem 3 – What is the ratio of the area of the Hubble mirror to the human pupil? This is called the Light Gathering Ability of the Hubble Space Telescope! Problem 4 - The faintest stars in the sky that the human eye can see are called magnitude +6.0 stars. -

BUILDING a SIMPLE REFRACTING TELESCOPE Grades 5–8

BUILDING A SIMPLE REFRACTING TELESCOPE grades 5–8 Objective To build a simple refracting telescope. Introduction A simple refracting telescope is very easy to create. All that is needed are two convex lenses and two cardboard tubes. The first part of this activity demonstrates the inner workings of a telescope, and the second part demonstrates how to construct a simple refracting telescope. The lenses that will be used in this telescope are very similar to the lenses used by Galileo Galilei in the 17th century. Within a refracting telescope there are two lenses: an objective lens and an eyepiece. Part 1 of the activity demonstrates how light passes through the first lens and is bent (or refracted) to a focal point. Using a blank piece of paper, students can see where the focused image is formed. When another lens is placed on the opposite side of the piece of paper it acts like a magnifier, making the image appear larger. This arrangement of lenses demonstrates the simplicity of the basic telescope. Part 2 of the activity demonstrates how to construct a telescope and use it to view distant objects. The same lenses used in part 1 can be used in part 2 with the cardboard tubes to hold the lenses in place. The tubes slide inside each other to focus the telescope. After observing the process of light refraction without a telescope tube, students should have a clear understanding of what happens when they point their simple telescope at a distant planet or object. Background Reading for Educators Telescopes: Super Views of Space, available at https://www.amnh.org/learn-teach/curriculum-collections/discovering-the-universe/ telescopes-super-views-from-space Developed with the generous support of The Charles Hayden Foundation BUILDING A SIMPLE REFRACTING TELESCOPE Materials Set of lenses Styrofoam cups These can be ordered from Sergeant- 40–75 Watt red bulb Welch (1-800-727-4368) Desk lamp or flashlight part # WL53200-38L A and B, Scissors $0.99/lens) Blank piece of paper Transparent tape Note: These lenses can also be Set of cardboard tubes purchased in sets of 20. -

Optical Telescopes

Optical Telescopes Introduction The night sky always attracted people by its charming mystery. Observers had been using naked eyes for their explorations for many centuries. Obviously, they could not achieve a lot due to eyesight limitations. It cannot be estimated, how important the invention of telescopes was for astronomers. It opened an enormous field for visual observations, which had lead to many brilliant discoveries. That happened in 1608, when the German-born Dutch eyeglass maker had guessed to combine several lenses and created the first telescope [PRAS]. This occasion is now almost forgotten, because no inventions were made but a Dutchman. His device was not used for astronomical purposes, and it found its application in military use. The event, which remains in people memories, is the Galilean invention of his first telescope in 1609. The first Galilean optical tube was very simple, it could only magnify objects three times. After several modifications, the scientist achieved higher optical power. This helped him to observe the venusian phases, lunar craters and four jovian satellites. The main tasks of a telescope are the following: • Gathering as much light radiation as possible • Increasing an angular separation between objects • Creating a focused image of an object We have now achieved high technical level, which enables us to create colossal telescopes, reaching distant regions of the Universe and making great discoveries. Telescope components The main parts of which any telescope consists with are the following: • Primary lens (for refracting telescopes), which is the main component of a device. Bigger the lens, more light a telescope can gather and fainter objects can be viewed. -

Chapter 7 Lenses

Chapter 7 Lenses Chapter 7 Lenses © C. Robert Bagnell, Jr., Ph.D., 2012 Lenses are the microscope’s jewels. Understanding their properties is critical in understanding the microscope. Objective, condenser, and eyepiece lenses have information about their properties inscribed on their housings. Table 7.1 is an example from objective lenses. This chapter will unfold the meaning and significance of these symbols. The three main categories of information are Numerical Aperture, Magnification / Tube Length, and Aberration Corrections. Zeiss Leitz Plan-Apochromat 170/0.17 63X/1.40 Oil Pl 40 / 0.65 ∞/0.17 Nikon Olympus Fluor 20 Ph3 ULWD CDPlan 40PL 0.75 0.50 160/0.17 160/0-2 Table 7.1 – Common Objective Lens Inscriptions Numerical Aperture & Resolution Figure 7.1 Inscribed on every objective lens and most 3 X condenser lenses is a number that indicates the lenses N.A. 0.12 resolving power – its numerical aperture or NA. For the Zeiss lens in table 7.1 it is 1.40. The larger the NA the better the resolving power. Ernst Abbe invented the concept of numerical aperture in 1873. However, prior to Abbe’s quantitative formulation of resolving power other people, such as Charles Spencer, intuitively understood the underlying principles and had used them to produce 1 4˚ superior lenses. Spencer and Angular Aperture 95 X So, here is a bit about Charles Spencer. In the mid N.A. 1.25 1850's microscopists debated the relationship of angular aperture to resolution. Angular aperture is illustrated in 110˚ Pathology 464 Light Microscopy 1 Chapter 7 Lenses figure 7.1.