Binocular and Spotting Scope Basics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How to Choose and Use Birding Optics

Blackburnian Warbler In association with Chestnut-sided Warbler CONTENTS Birding Optics 101 . 2 Optics Terms . 3 How Binoculars Work . 6 All About Spotting Scopes . 10 Top 10 Tips for Purchasing Your First Optics . 14 Adjusting Your Birding Optics . 18 Become a Birder in 5 Simple Steps . 22 Identifying Birds . 24 Three Tips for IDing Birds . 26 Traveling With Optics . 28 BIRDING OPTICS 101 No bird watcher’s toolkit is complete without optics, which means binoculars or a spotting scope . While you can bird without the magnifying power of optics, you won’t always get a satisfactory look at the birds, and will likely miss a few IDs . One barrier to entry for aspiring birders is the belief that quality optics are expensive . They can be, but they don’t have to be . Technological and manufacturing advances mean that today’s binoculars and spotting scopes are more affordable than ever, while still featuring high-end materials . So, where do you begin when selecting your first birding optics? In this guide, we discuss how binoculars and spotting scopes work, so you can select the best optics to enhance your birding experience . Once you’ve made your choice, we’ll teach you how to clean and care for your optics . You will learn to love them, because they are your gateway to discovering flocks’ worth of amazing birds . OPTICS DEFINED: WHAT YOU SEE IS WHAT YOU GET The vast majority of birders use binoculars—also known as “binos,” “binocs,” or “bins” for short . When you hear birders use the term “optics,” they are usually referring to binoculars . -

S P O R T O P T I

KENKO-SPORT-OPTICS-2012-1 12.4.6 11:07 AM Page 1 SPORT OPTICS BIRDING SPORTS MARINE OUTDOOR TRAVEL EVENTS ASTRONOMY KENKO-SPORT-OPTICS-2012-1 12.4.6 11:07 AM Page 2 KENKO-SPORT-OPTICS-2012-1 12.4.6 11:07 AM Page 3 In a moment, the breadth and beauty of nature is real, inviting you into its world... The sea, mountains, fields, forests and blue sky... see the full grandeur of nature through our outstanding line of binoculars. RECOMMENDED NEW ITEMS OP 8x32 DH II 8X21 DH SG OP 10x32W DH II 10X25 DH SG BIRDING BINOCULARS For more information, please refer to page 8 For more information, please refer to page 15 KENKO-SPORT-OPTICS-2012-1 12.4.6 11:07 AM Page 4 INDEX As one of the world's largest makers of binoculars, Kenko has the experience and refined manufacturing techniques to produce high-quality, multi-coated and phase-coated glass optics that yield bright, crisp clear viewing under a wide-variety of conditions. You may not know the name, but the Kenko company is an original manufacturer with decades of experience in the precise production of sports optics. THE PRODUCTION PROCESS OF KENKO BINOCULARS INDEX BINOCULARS Kenko - ULTIMATE BIRDING BINOCULARS OP 8x42DH Mark II / OP 10x42DH Mark II, 8x42DH MS / 10x42DH MS . .6 8x32DH MS / 10x32DH MS, 8x25DH / 10x25D . .7 ultra VIEW EX - PREMIUM BIRDING BINOCULARS OP 8x32 DH II / OP 10x32W DH II, OP 8x42 DH ED / OP 10x42 DH ED . .8 OP 8x42 DH II / OP 10x42 DH II, 10x50 DH / 12x50 DH, 8x42 DH / 10x42 DH . -

Optical & Sport Systems

PRODUCT GUIDE No. 46 ◆ 9 •20 7 1 9 4 1 Optical & Sport Systems 3 5 t h Ye a r BINOCULARS TELESCOPES MICROSCOPES OUTDOOR ◆ INDEX BINOCULARS & SPOTTERS SPECS Konus is tradition and innovation. The tradition of an historic and prestigious brand that Konus binoculars and spotting scopes are made with an uncompromising commit- has become a synonymours of uncompromising quality and excellenge in the optics ment to quality at its highest standards. Their superior components ensure the ultimate industry over the last years and is currently distributed in 76 Countries worldwide. viewing experience for every demanding user. Featuring a wide assortment of models The innovation of a creative approach to the market that takes place through the con- with distinctive specifications (compact, zoom, waterproof, etc.), our lines of binoculars stant development of exclusive products with an unique and original style in both their and spotting scopes have become the favourite choice of avid hunters, birdwatchers design and packaging. In the competitive and challenging market of nowadays, Konus and outdoorsmen. is able to offer the ideal solution for every possible need, from Hunting to Birdwatching, from Research to Astonomiy, from Science to Sport. MAGNIFICATION: EYE RELIEF: This is the number of times that an object is being enlarged whi- this is the distance a binocular/spotting scope can be held away le looking at it through a binocular/spotting scope. For example, from the eye and still maintain the full field of view. Long eye BINOCULARS ◆ MAGNIFIERS an object that is 100 yards away will appear like it is 5 yards relief optics reduce eyestrain and are much more comfortable, away if it is observed with a 20x instrument (100 : 20 = 5). -

The Microscope Parts And

The Microscope Parts and Use Name:_______________________ Period:______ Historians credit the invention of the compound microscope to the Dutch spectacle maker, Zacharias Janssen, around the year 1590. The compound microscope uses lenses and light to enlarge the image and is also called an optical or light microscope (vs./ an electron microscope). The simplest optical microscope is the magnifying glass and is good to about ten times (10X) magnification. The compound microscope has two systems of lenses for greater magnification, 1) the ocular, or eyepiece lens that one looks into and 2) the objective lens, or the lens closest to the object. Before purchasing or using a microscope, it is important to know the functions of each part. Eyepiece Lens: the lens at the top that you look through. They are usually 10X or 15X power. Tube: Connects the eyepiece to the objective lenses Arm: Supports the tube and connects it to the base. It is used along with the base to carry the microscope Base: The bottom of the microscope, used for support Illuminator: A steady light source (110 volts) used in place of a mirror. Stage: The flat platform where you place your slides. Stage clips hold the slides in place. Revolving Nosepiece or Turret: This is the part that holds two or more objective lenses and can be rotated to easily change power. Objective Lenses: Usually you will find 3 or 4 objective lenses on a microscope. They almost always consist of 4X, 10X, 40X and 100X powers. When coupled with a 10X (most common) eyepiece lens, we get total magnifications of 40X (4X times 10X), 100X , 400X and 1000X. -

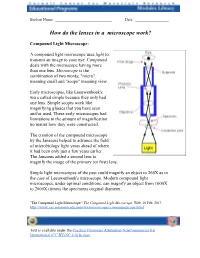

How Do the Lenses in a Microscope Work?

Student Name: _____________________________ Date: _________________ How do the lenses in a microscope work? Compound Light Microscope: A compound light microscope uses light to transmit an image to your eye. Compound deals with the microscope having more than one lens. Microscope is the combination of two words; "micro" meaning small and "scope" meaning view. Early microscopes, like Leeuwenhoek's, were called simple because they only had one lens. Simple scopes work like magnifying glasses that you have seen and/or used. These early microscopes had limitations to the amount of magnification no matter how they were constructed. The creation of the compound microscope by the Janssens helped to advance the field of microbiology light years ahead of where it had been only just a few years earlier. The Janssens added a second lens to magnify the image of the primary (or first) lens. Simple light microscopes of the past could magnify an object to 266X as in the case of Leeuwenhoek's microscope. Modern compound light microscopes, under optimal conditions, can magnify an object from 1000X to 2000X (times) the specimens original diameter. "The Compound Light Microscope." The Compound Light Microscope. Web. 16 Feb. 2017. http://www.cas.miamioh.edu/mbi-ws/microscopes/compoundscope.html Text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International (CC BY-NC 4.0) license. - 1 – Student Name: _____________________________ Date: _________________ Now we will describe how a microscope works in somewhat more detail. The first lens of a microscope is the one closest to the object being examined and, for this reason, is called the objective. -

Scope & Spotting Scope Resolution and Magnification

Scope & Spotting Scope Resolution and Magnification Eyesight Resolution Limits The normal or median human visual resolution limit is 1 MOA (minute of angle). This is also called normal visual acuity when use by your eye doctor. On the typical Snellen eye chart, the 20/20 line (20 foot line in USA) or 6/6 line (6 meters in the rest of the world) was designed to be readable with a visual resolution or acuity of 1 MOA. The other lines/characters are scaled accordingly. Telescopes were developed as visual aids to overcome this limited visual resolution or acuity. The principal tool for resolution improvement is magnification. It is obvious that magnification increases the apparent size of objects. However and more importantly magnification increases visual resolution. In the following illustration note how even small (doublings – powers of 2) increases in magnification greatly increase our ability to resolve (distinguish) small but important details by both increasing their apparent size and making better use of the available field of view. Fred Bohl, 10 June 2007 Page 1 of 6 Scope & Spotting Scope Resolution and Magnification Scope Resolution Limits Diffraction Limited Optics A long historical record holds that diffraction defines the ultimate resolution limit of telescopes. Generally we can say that any aperture with a finite size will cause diffraction and hence its resolution will be limited. The finite aperture (front lens, main mirror) must cut off a part of the incoming plane wave front. This missing part is disturbing the otherwise perfect interference of the propagating waves in a certain way. The result is a modulation of the wave front called the Point Spread Function (PSF). -

C5 Spotting Scope XLT 52291

C5 Spotting Scope - #52291 Instruction Manual A spotting scope is nothing more than a telescope that is designed to look around the Earth. Unlike astronomical telescopes, which produce inverted or reverted images, spotting scopes produce correctly oriented images. Celestron offers several different models, each of which uses the highest quality optics to produce the best possible images. All models have rugged, durable housings to give you a lifetime of pleasure with a minimal amount of maintenance. Your Celestron spotting scope is designed to give you hours of fun and rewarding observations. There are, however, a few things to consider before using your spotting scope that will ensure your safety and protect your equipment. • Never look directly at the Sun with the naked eye or with your spotting scope. Permanent and irreversible eye damage may result. • Never use your spotting scope to project an image of the Sun onto any surface. Internal heat build-up can damage your spotting scope and/or any accessories attached to it. • Never use an eyepiece solar filter or a Herschel wedge. Internal heat build- up inside your spotting scope can cause these devices to crack or break, allowing unfiltered sunlight to pass through to the eye. • Never leave your spotting scope unsupervised, either when children are present or adults who may not be familiar with the correct operating procedures of your spotting scope. • Never point your spotting scope at the Sun unless you have the proper solar filter. We recommend Celestron solar filters only. Don't take chances -- use Celestron filters for safety and performance! When using your spotting scope with the proper solar filter, ALWAYS cover the finderscope. -

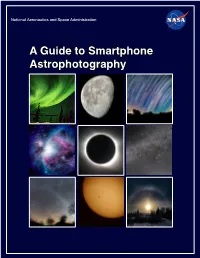

A Guide to Smartphone Astrophotography National Aeronautics and Space Administration

National Aeronautics and Space Administration A Guide to Smartphone Astrophotography National Aeronautics and Space Administration A Guide to Smartphone Astrophotography A Guide to Smartphone Astrophotography Dr. Sten Odenwald NASA Space Science Education Consortium Goddard Space Flight Center Greenbelt, Maryland Cover designs and editing by Abbey Interrante Cover illustrations Front: Aurora (Elizabeth Macdonald), moon (Spencer Collins), star trails (Donald Noor), Orion nebula (Christian Harris), solar eclipse (Christopher Jones), Milky Way (Shun-Chia Yang), satellite streaks (Stanislav Kaniansky),sunspot (Michael Seeboerger-Weichselbaum),sun dogs (Billy Heather). Back: Milky Way (Gabriel Clark) Two front cover designs are provided with this book. To conserve toner, begin document printing with the second cover. This product is supported by NASA under cooperative agreement number NNH15ZDA004C. [1] Table of Contents Introduction.................................................................................................................................................... 5 How to use this book ..................................................................................................................................... 9 1.0 Light Pollution ....................................................................................................................................... 12 2.0 Cameras ................................................................................................................................................ -

Astrophotography Tales of Trial & Error

Astrophotography Tales of Trial & Error Dave & Marie Allen AVAC 13th April 2001 Contents Photos Through Camera Lens magnification Increasing 1 Star trails 2 Piggy back Photos Through the Telescope 3 Prime focus 4 Photo through the eyepiece 5 Eyepiece projection Camera Basics When the photograph is being exposed, Light directed to viewfinder the light is directed onto the film. The viewfinder is completely black. Usual photographic rules apply: Less light ! Longer exposures Higher f number ! Longer exposures Light directed to film Star Motion Stars rise and set – just like the Sun in the daytime. The motion of the stars can cause problems for astrophotography Star Motion Stars rise and set – just like the Sun in the daytime. The motion of the stars can cause problems for astrophotography Star Motion Stars rise and set – just like the Sun in the daytime. The motion of the stars can cause problems for astrophotography Star Motion Stars rise and set – just like the Sun in the daytime. The motion of the stars can cause problems for astrophotography Star Motion Stars rise and set – just like the Sun in the daytime. The motion of the stars can cause problems for astrophotography Tracking the motion of the stars during the exposure is called “guiding”. Requires a polar aligned mount and periodic corrections to keep the subject stationary relative to the camera. Done using slow motion controls – or more often with dual axis correctors. Guiding Photography Technique Guiding Required? Star trails No Piggy back Yes Prime focus Yes Photo through the -

Lab 11: the Compound Microscope

OPTI 202L - Geometrical and Instrumental Optics Lab 8-1 LAB 8: BINOCULARS Prism binoculars are, in reality, a pair of refractive telescopes mounted side by side, one for each of the two eyes. The advantages of binoculars over a single monocular telescope are mainly (1) corrected image orientation and (2) depth perception. Three-dimensional information gathered by using both eyes is also enhanced by the binoculars because of the wide separation of objective lenses (approximately 125 mm) compared with the typical InterPupilary Distance (IPD) of human eyes (approximately 68 mm). Binoculars use either Porro or Roof prisms between the objectives and eyepieces to provide correct image orientation. Porro binoculars are shown in Figure 8.1, with part of the case cut away to show the optical parts. The objectives are cemented achromatic pairs (doublets), or triplets, while the oculars are Kellner or achromatized Ramsden eyepieces. The dotted lines show the path of an axial ray through one pair of Porro prisms. The prisms rotate the image by 180°, so the final image is correct (the image looks the same as the object). The doubling back of the light rays in the Porro prism design has the further advantage of enabling longer focus objectives to be used in short tubes, with consequent high magnification. Figure 8.2 shows Porro prims and Roof prisms. Binoculars have many applications that sometimes have different requirements. Characteristics to take into account are (1) magnification, (2) field of view, (3) light- gathering power, and (4) size and weight. Generally, higher magnification results in narrow fields of view and vice versa. -

Chapter 8 the Telescope

Chapter 8 The Telescope 8.1 Purpose In this lab, you will measure the focal lengths of two lenses and use them to construct a simple telescope which inverts the image like the one developed by Johannes Kepler. Because one lens has a large focal length and the other lens has a small focal length, you will use different methods of determining the focal lengths than was used in ’Optics of Thin Lenses’ lab. 8.2 Introduction 8.2.1 A Brief History of the Early Telescope Although eyeglass-makers had been experimenting with lenses well before 1600, the first mention of a telescope appears in a letter written in 1608 by Hans Lippershey, a Dutch spectacle maker, seeking a patent for a telescope. The patent was denied because of easy telescope duplication and difficulty in patent enforcement. The instrument spread rapidly. Galileo heard of it in the early 1600s and quickly made improvements in lens grinding that increased the magnification from a relatively low value of 2 to as much as 30. With these more powerful telescopes, he observed the Milky Way, the mountains on the Moon, the phases of Venus, and the moons of Jupiter. These early telescopes were a type of ‘opera glass,’ producing erect or ‘right side up’ images but having limited magnification. When Johannes Kepler, a German mathematician and astronomer working in Prague under Tycho Brahe, heard of Galileo’s discoveries, he perfected a different form of telescope. Although Kepler’s design inverts the image, it is much more powerful than the Galilean type. This lab we will use the lenses supplied with the telescope kit. -

20-60X60 Spotting Scope Users Manual

81011_20_60x60_Englsh_Grt_Ocn_HUBBLE_R3.qxd 2/14/11 5:10 PM Page 1 Objective Focus Lens Optical Sunshade Instruction Manual Knob 45° Eyepiece Tube Meade Spotting Scope Zoom Introduction Ring Mounting Meade spotting scopes are ideal for high-magnification, high- Mounting Head resolution observation of terrestrial subjects. Explore the Platform subtleties of a bird’s feather structure from 50 yards or use the Spotting Scope for casual astronomical observations. Quick Side Tilt Note: “Spotting Scope” is a term used to define a telescope Mount Locking Nut that is primarily intended for terrestrial (land) viewing. Latch spotting scopes can also be used for casual astronomical Elevation observing. Crank Pan Lever Handle Never use a Meade® Spotting Scope to look at the Sun! Looking at or near the Sun will cause instant and Elevation irreversible damage to your eye. Eye damage is Height Vertical often painless, so there is no warning to the Locking Lock observer that damage has occurred until it is too Nut late. Do not point the spotting scope or its viewfinder at or near the Sun. Do not look through the spotting scope as it is Tripod moving. Children should always have adult supervision while observing. Leg Locking Lever 1 81011_20_60x60_Englsh_Grt_Ocn_HUBBLE_R3.qxd 2/14/11 5:10 PM Page 2 Parts The following parts are included with the spotting scope: • The spotting scope optical tube. • Tripod • Hard and soft carry cases How to attach the spotting scope to the tripod: 1. Spread out the tripod legs and place the tripod on a level surface. Extend the legs to full height, if necessary.