Lab 11: the Compound Microscope

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Telescopes and Binoculars

Continuing Education Course Approved by the American Board of Opticianry Telescopes and Binoculars National Academy of Opticianry 8401 Corporate Drive #605 Landover, MD 20785 800-229-4828 phone 301-577-3880 fax www.nao.org Copyright© 2015 by the National Academy of Opticianry. All rights reserved. No part of this text may be reproduced without permission in writing from the publisher. 2 National Academy of Opticianry PREFACE: This continuing education course was prepared under the auspices of the National Academy of Opticianry and is designed to be convenient, cost effective and practical for the Optician. The skills and knowledge required to practice the profession of Opticianry will continue to change in the future as advances in technology are applied to the eye care specialty. Higher rates of obsolescence will result in an increased tempo of change as well as knowledge to meet these changes. The National Academy of Opticianry recognizes the need to provide a Continuing Education Program for all Opticians. This course has been developed as a part of the overall program to enable Opticians to develop and improve their technical knowledge and skills in their chosen profession. The National Academy of Opticianry INSTRUCTIONS: Read and study the material. After you feel that you understand the material thoroughly take the test following the instructions given at the beginning of the test. Upon completion of the test, mail the answer sheet to the National Academy of Opticianry, 8401 Corporate Drive, Suite 605, Landover, Maryland 20785 or fax it to 301-577-3880. Be sure you complete the evaluation form on the answer sheet. -

Astronomical Binoculars

30˚E 15˚E OWNER’S MANUAL ASTRONOMICAL BINOCULARS ZHUMELL 20X80 SUPERGIANT ASTRONOMICAL BINOCULARS 0˚ 15˚W 75˚W 60˚W 30˚W 45˚W Zhumell customers know that there are plenty of ways to experience the world. They also understand that, however you choose to explore it, the best experience is one that fully immerses you in the world’s most striking details. That’s where our optics products come in. We strive to put high-performance products in the hands of our customers so that they can experience the world up close, with their own eyes. With Zhumell, you get field-tested, precision-crafted optics at the best possible value. So even if you’re just starting out as an amateur birder or astronomer, you don’t have to settle for entry-level products. Zhumell customers enjoy life’s pursuits, hobbies, and adventures in rich, colorful detail- the kind of detail that only high-performance optics can produce. At Zhumell, we design our binoculars, telescopes, and spotting scopes for discerning, price-conscious users who are uncompromising on quality. If you’re looking for accessibly priced optics that will bring your world within reach, you’re looking for Zhumell. Enjoy the view. 2 ENJOYING YOUR ZHUMELL ASTRONOMICAL BINOCULARS 1. Caring For Your Binoculars 2. Using Your Binoculars i. Tripod Mounting ii. Interpupillary Distance iii. Center and Diopter Focus 3. Terrestrial and Astronomical Viewing 4. Astronomical Observation Tips i. Selecting a Viewing Site ii. Seeing and Transparency iii. Dark-Adapting iv. Tracking Celestial Objects 5. Cool Views i. The Moon ii. -

Viewing an Eclipse Safely

ECLIPSES SOLAR an eclipse safely How to observe SOLAR ECLIPSE, OCTOBER 2014, BY LEMAN NORTHWAY Solar eclipses are quite rare and are often a major event. The SOLAR ECLIPSES Moon passes right in front of the Sun, blotting out its disc. Every time a solar eclipse occurs there are various things to look for. However, it is extremely dangerous to just go out and look up. The Sun is so bright that just looking at it can blind you, so you’ll need to prepare beforehand. There are various ways to observe eclipses safely, using both everyday materials and telescopes or binoculars. So read this leaflet Introduction to find out what happens during an eclipse and how you can see all the stages of the event safely. This booklet was written by the Royal Astronomical Society with The Society for Popular Astronomy and is endorsed by the British Astronomical Association The Royal Astronomical The Society for Popular Formed in 1890, the Society, founded in Astronomy is for British Astronomical 1820, encourages and beginners of all ages. Our Association has an promotes the study of aim is to make astronomy international reputation astronomy, solar-system fun, and our magazine, for the quality of science, geophysics and Popular Astronomy, is full its observational closely related branches of information to help and scientific work. of science. you get to know the Membership is open to www.ras.org.uk sky and get involved. We even have a special Young all persons interested in HIGGS-BOSON.COM JOHNSON: PAUL BY D Stargazers section, run by TV’s Lucie Green. -

The Microscope Parts And

The Microscope Parts and Use Name:_______________________ Period:______ Historians credit the invention of the compound microscope to the Dutch spectacle maker, Zacharias Janssen, around the year 1590. The compound microscope uses lenses and light to enlarge the image and is also called an optical or light microscope (vs./ an electron microscope). The simplest optical microscope is the magnifying glass and is good to about ten times (10X) magnification. The compound microscope has two systems of lenses for greater magnification, 1) the ocular, or eyepiece lens that one looks into and 2) the objective lens, or the lens closest to the object. Before purchasing or using a microscope, it is important to know the functions of each part. Eyepiece Lens: the lens at the top that you look through. They are usually 10X or 15X power. Tube: Connects the eyepiece to the objective lenses Arm: Supports the tube and connects it to the base. It is used along with the base to carry the microscope Base: The bottom of the microscope, used for support Illuminator: A steady light source (110 volts) used in place of a mirror. Stage: The flat platform where you place your slides. Stage clips hold the slides in place. Revolving Nosepiece or Turret: This is the part that holds two or more objective lenses and can be rotated to easily change power. Objective Lenses: Usually you will find 3 or 4 objective lenses on a microscope. They almost always consist of 4X, 10X, 40X and 100X powers. When coupled with a 10X (most common) eyepiece lens, we get total magnifications of 40X (4X times 10X), 100X , 400X and 1000X. -

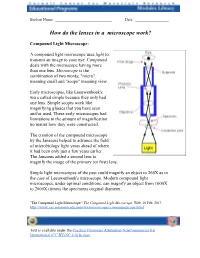

How Do the Lenses in a Microscope Work?

Student Name: _____________________________ Date: _________________ How do the lenses in a microscope work? Compound Light Microscope: A compound light microscope uses light to transmit an image to your eye. Compound deals with the microscope having more than one lens. Microscope is the combination of two words; "micro" meaning small and "scope" meaning view. Early microscopes, like Leeuwenhoek's, were called simple because they only had one lens. Simple scopes work like magnifying glasses that you have seen and/or used. These early microscopes had limitations to the amount of magnification no matter how they were constructed. The creation of the compound microscope by the Janssens helped to advance the field of microbiology light years ahead of where it had been only just a few years earlier. The Janssens added a second lens to magnify the image of the primary (or first) lens. Simple light microscopes of the past could magnify an object to 266X as in the case of Leeuwenhoek's microscope. Modern compound light microscopes, under optimal conditions, can magnify an object from 1000X to 2000X (times) the specimens original diameter. "The Compound Light Microscope." The Compound Light Microscope. Web. 16 Feb. 2017. http://www.cas.miamioh.edu/mbi-ws/microscopes/compoundscope.html Text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International (CC BY-NC 4.0) license. - 1 – Student Name: _____________________________ Date: _________________ Now we will describe how a microscope works in somewhat more detail. The first lens of a microscope is the one closest to the object being examined and, for this reason, is called the objective. -

Binocular and Spotting Scope Basics

Binocular and Spotting Scope Basics A good pair of binoculars is a must for most for bird monitoring projects. Certainly, you can observe birds and other wildlife without the aid of binoculars, such as at a feeder, but with them you will see more detail. Binoculars don't have to cost you a lot of money, but should adequately magnify birds for identification. Many 7 x 35 or 8 x 42 power binoculars are affordable and good for bird watching. They should be easy to use and comfortable for you. You can buy binoculars through sporting goods stores, catalogs, and the Internet. How to use binoculars Binoculars are an extension of your eyes. First, use your naked eye to find the birds you are observing. Once you have detected movement and can see the wildlife, use binoculars to see details of a bird’s “field marks.” Everyone’s eyes are different, so before you raise the binoculars, you must calibrate them for your eyes. How to Calibrate Binoculars 1. Binoculars hinge at the center between the two large “barrels,” allowing the eyepieces to fit the width of your eyes (Illustration A). Pivot the hinged barrels so you see a single circle-shaped image, rather than a double-image when looking through them. If the barrels are as close together as they go and you still see two images, you may need to find another pair. The distance between the eyepieces is called the “interpupillary distance.” It is too large if you see two images. The number on the hinge post (angle) will always be the same for your eyes, no matter which binocular you use (A). -

Can You Spot the Sunspots?

Spot the Sunspots Can you spot the sunspots? Description Use binoculars or a telescope to identify and track sunspots. You’ll need a bright sunny day. Age Level: 10 and up Materials • two sheets of bright • Do not use binoculars whose white paper larger, objective lenses are 50 • a book mm or wider in diameter. • tape • Binoculars are usually described • binoculars or a telescope by numbers like 7 x 35; the larger • tripod number is the diameter in mm of • pencil the objective lenses. • piece of cardboard, • Some binoculars cannot be easily roughly 30 cm x 30 cm attached to a tripod. • scissors • You might need to use rubber • thick piece of paper, roughly bands or tape to safely hold the 10 cm x 10 cm (optional) binoculars on the tripod. • rubber bands (optional) Time Safety Preparation: 5 minutes Do not look directly at the sun with your eyes, Activity: 15 minutes through binoculars, or through a telescope! Do not Cleanup: 5 minutes leave binoculars or a telescope unattended, since the optics can be damaged by too much Sun exposure. 1 If you’re using binoculars, cover one of the objective (larger) lenses with either a lens cap or thick piece of folded paper (use tape, attached to the body of the binoculars, to hold the paper in position). If using a telescope, cover the finderscope the same way. This ensures that only a single image of the Sun is created. Next, tape one piece of paper to a book to make a stiff writing surface. If using binoculars, trace both of the larger, objective lenses in the middle of the piece of cardboard. -

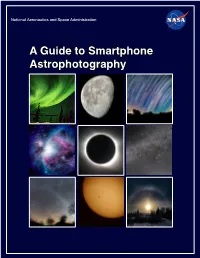

A Guide to Smartphone Astrophotography National Aeronautics and Space Administration

National Aeronautics and Space Administration A Guide to Smartphone Astrophotography National Aeronautics and Space Administration A Guide to Smartphone Astrophotography A Guide to Smartphone Astrophotography Dr. Sten Odenwald NASA Space Science Education Consortium Goddard Space Flight Center Greenbelt, Maryland Cover designs and editing by Abbey Interrante Cover illustrations Front: Aurora (Elizabeth Macdonald), moon (Spencer Collins), star trails (Donald Noor), Orion nebula (Christian Harris), solar eclipse (Christopher Jones), Milky Way (Shun-Chia Yang), satellite streaks (Stanislav Kaniansky),sunspot (Michael Seeboerger-Weichselbaum),sun dogs (Billy Heather). Back: Milky Way (Gabriel Clark) Two front cover designs are provided with this book. To conserve toner, begin document printing with the second cover. This product is supported by NASA under cooperative agreement number NNH15ZDA004C. [1] Table of Contents Introduction.................................................................................................................................................... 5 How to use this book ..................................................................................................................................... 9 1.0 Light Pollution ....................................................................................................................................... 12 2.0 Cameras ................................................................................................................................................ -

Nikon Binocular Handbook

THE COMPLETE BINOCULAR HANDBOOK While Nikon engineers of semiconductor-manufactur- FINDING THE ing equipment employ our optics to create the world’s CONTENTS PERFECT BINOCULAR most precise instrumentation. For Nikon, delivering a peerless vision is second nature, strengthened over 4 BINOCULAR OPTICS 101 ZOOM BINOCULARS the decades through constant application. At Nikon WHAT “WATERPROOF” REALLY MEANS FOR YOUR NEEDS 5 THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN POWER, Sport Optics, our mission is not just to meet your THE DESIGN EYE RELIEF, AND FIELD OF VIEW The old adage “the better you understand some- PORRO PRISM BINOCULARS demands, but to exceed your expectations. ROOF PRISM BINOCULARS thing—the more you’ll appreciate it” is especially true 12-14 WHERE QUALITY AND with optics. Nikon’s goal in producing this guide is to 6-11 THE NUMBERS COUNT QUANTITY COUNT not only help you understand optics, but also the EYE RELIEF/EYECUP USAGE LENS COATINGS EXIT PUPIL ABERRATIONS difference a quality optic can make in your appre- REAL FIELD OF VIEW ED GLASS AND SECONDARY SPECTRUMS ciation and intensity of every rare, special and daily APPARENT FIELD OF VIEW viewing experience. FIELD OF VIEW AT 1000 METERS 15-17 HOW TO CHOOSE FIELD FLATTENING (SUPER-WIDE) SELECTING A BINOCULAR BASED Nikon’s WX BINOCULAR UPON INTENDED APPLICATION LIGHT DELIVERY RESOLUTION 18-19 BINOCULAR OPTICS INTERPUPILLARY DISTANCE GLOSSARY DIOPTER ADJUSTMENT FOCUSING MECHANISMS INTERNAL ANTIREFLECTION OPTICS FIRST The guiding principle behind every Nikon since 1917 product has always been to engineer it from the inside out. By creating an optical system specific to the function of each product, Nikon can better match the product attri- butes specifically to the needs of the user. -

Hide & Seek Moon

Hide & Seek Moon Children use binoculars to search for small items that an astronaut lost while walking on the Moon. The Moon is pictured on a banner hanging a short distance away. 15 minutes Drop-in 1–4 children at a time Content Learning Goals Materials • Children notice that binoculars make distant objects • Moon Banner appear closer/bigger. • Child-friendly binoculars* • Children begin to understand that binoculars help us • Small black & white images of items to tape see more detail in distant objects. to the Moon (page 7) • Astronaut sign (page 8) Optional: • Photo of the Moon (page 9) • Markers Science Practices • Children observe changes in how objects appear (bigger/closer) when using binoculars. • Children use a tool to better see the small images. SET-UP • Hang the Moon banner on a wall. • Cut out the pictures of the ten items the astronaut lost (page 7). Tape them to the Moon on the banner. • Place a short table or bench with one or more sets of binoculars about 10–12 feet from the wall with nothing obstructing the view of the Moon. Try to choose a distance such that it is difficult to recognize the items with the unaided eye, but easy with the binoculars, keeping in mind young children have sharper eyesight than adults. The ideal distance will depend on the lighting in the room. • For a drop-in program, place the astronaut sign (see page 8) on the table for parents to read to their children. * We recommend using binoculars that are visually appealing to children, properly sized for their small faces, intuitive to use, and have quality optics for a clear view. -

Astrophotography Tales of Trial & Error

Astrophotography Tales of Trial & Error Dave & Marie Allen AVAC 13th April 2001 Contents Photos Through Camera Lens magnification Increasing 1 Star trails 2 Piggy back Photos Through the Telescope 3 Prime focus 4 Photo through the eyepiece 5 Eyepiece projection Camera Basics When the photograph is being exposed, Light directed to viewfinder the light is directed onto the film. The viewfinder is completely black. Usual photographic rules apply: Less light ! Longer exposures Higher f number ! Longer exposures Light directed to film Star Motion Stars rise and set – just like the Sun in the daytime. The motion of the stars can cause problems for astrophotography Star Motion Stars rise and set – just like the Sun in the daytime. The motion of the stars can cause problems for astrophotography Star Motion Stars rise and set – just like the Sun in the daytime. The motion of the stars can cause problems for astrophotography Star Motion Stars rise and set – just like the Sun in the daytime. The motion of the stars can cause problems for astrophotography Star Motion Stars rise and set – just like the Sun in the daytime. The motion of the stars can cause problems for astrophotography Tracking the motion of the stars during the exposure is called “guiding”. Requires a polar aligned mount and periodic corrections to keep the subject stationary relative to the camera. Done using slow motion controls – or more often with dual axis correctors. Guiding Photography Technique Guiding Required? Star trails No Piggy back Yes Prime focus Yes Photo through the -

4.4 Total Internal Reflection

n 1:33 sin θ = water sin θ = sin 35◦ ; air n water 1:00 air i.e. ◦ θair = 49:7 : Thus, the height above the horizon is ◦ ◦ θ = 90 θair = 40:3 : (4.7) − Because the sun is far away from the fisherman and the diver, the fisherman will see the sun at the same angle above the horizon. 4.4 Total Internal Reflection Suppose that a light ray moves from a medium of refractive index n1 to one in which n1 > n2, e.g. glass-to-air, where n1 = 1:50 and n2 = 1:0003. ◦ If the angle of incidence θ1 = 10 , then by Snell's law, • n 1:50 θ = sin−1 1 sin θ = sin−1 sin 10◦ 2 n 1 1:0003 2 = sin−1 (0:2604) = 15:1◦ : ◦ If the angle of incidence is θ1 = 50 , then by Snell's law, • n 1:50 θ = sin−1 1 sin θ = sin−1 sin 50◦ 2 n 1 1:0003 2 = sin−1 (1:1487) =??? : ◦ So when θ1 = 50 , we have a problem: Mathematically: the angle θ2 cannot be computed since sin θ2 > 1. • 142 Physically: the ray is unable to refract through the boundary. Instead, • 100% of the light reflects from the boundary back into the prism. This process is known as total internal reflection (TIR). Figure 8672 shows several rays leaving a point source in a medium with re- fractive index n1. Figure 86: The refraction and reflection of light rays with increasing angle of incidence. The medium on the other side of the boundary has n2 < n1.