Chapter 7 Lenses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Galileo and the Telescope

Galileo and the Telescope A Discussion of Galileo Galilei and the Beginning of Modern Observational Astronomy ___________________________ Billy Teets, Ph.D. Acting Director and Outreach Astronomer, Vanderbilt University Dyer Observatory Tuesday, October 20, 2020 Image Credit: Giuseppe Bertini General Outline • Telescopes/Galileo’s Telescopes • Observations of the Moon • Observations of Jupiter • Observations of Other Planets • The Milky Way • Sunspots Brief History of the Telescope – Hans Lippershey • Dutch Spectacle Maker • Invention credited to Hans Lippershey (c. 1608 - refracting telescope) • Late 1608 – Dutch gov’t: “ a device by means of which all things at a very great distance can be seen as if they were nearby” • Is said he observed two children playing with lenses • Patent not awarded Image Source: Wikipedia Galileo and the Telescope • Created his own – 3x magnification. • Similar to what was peddled in Europe. • Learned magnification depended on the ratio of lens focal lengths. • Had to learn to grind his own lenses. Image Source: Britannica.com Image Source: Wikipedia Refracting Telescopes Bend Light Refracting Telescopes Chromatic Aberration Chromatic aberration limits ability to distinguish details Dealing with Chromatic Aberration - Stop Down Aperture Galileo used cardboard rings to limit aperture – Results were dimmer views but less chromatic aberration Galileo and the Telescope • Created his own (3x, 8-9x, 20x, etc.) • Noted by many for its military advantages August 1609 Galileo and the Telescope • First observed the -

Single Pass Cooling Systems

A Sustainable Alternative to Single Pass Cooling Systems Amorette Getty, PhD Co-Director, LabRATS What is Single Pass Cooling? ● Used for distillation/reflux condensers, ice maker condensers, autoclaves, cage washers… ● Use a continuous flow of water from faucet to sewer o 0.25-2 gallons per minute, o up to 1,000,000 gallons of water/year if left on continuously Single Pass Cooling: Support ● “U.S. Environmental Protection Agency has ranked the elimination of single-pass cooling systems #4 on its list of top ten water management techniques” -Steve Buratto, Chair of Chemistry and Biochemistry department NOT Just a Sustainability Issue! California Nanosystems Institute (CNSI) flood in a second-floor laboratory in July, 2014. Water ran at ~1-2 gallons per minute for 6-10 hours, overflowing into a ground floor electron microscopy lab CNSI Flood Losses ● $ 2.2 Million in custom built research equipment ● Research shutdown for 4 months ● over 200 hours of staff time ● Insurance no longer covering this type of incident again Campus Responses to the Incident • CNSI ban on single pass cooling systems • TGIF grant financial incentive for optional change of single replacement systems • Chemistry and Material Research Laboratory (MRL) • Additional Grants being sought • Conversation at Campus and UC-level to regulate and replace these types of systems. Seeking Allies… ● “The replacement of single-pass cooling systems with closed-loop and water free systems would save water and represent a major advance in the sustainability efforts of the campus.” -Steve Buratto, Chair of Chemistry and Biochemistry department Barriers to Replacement ● “...major obstacle to replacing the single-pass cooling systems with closed-loop and water- free systems is cost. -

Introduction to CODE V: Optics

Introduction to CODE V Training: Day 1 “Optics 101” Digital Camera Design Study User Interface and Customization 3280 East Foothill Boulevard Pasadena, California 91107 USA (626) 795-9101 Fax (626) 795-0184 e-mail: [email protected] World Wide Web: http://www.opticalres.com Copyright © 2009 Optical Research Associates Section 1 Optics 101 (on a Budget) Introduction to CODE V Optics 101 • 1-1 Copyright © 2009 Optical Research Associates Goals and “Not Goals” •Goals: – Brief overview of basic imaging concepts – Introduce some lingo of lens designers – Provide resources for quick reference or further study •Not Goals: – Derivation of equations – Explain all there is to know about optical design – Explain how CODE V works Introduction to CODE V Training, “Optics 101,” Slide 1-3 Sign Conventions • Distances: positive to right t >0 t < 0 • Curvatures: positive if center of curvature lies to right of vertex VC C V c = 1/r > 0 c = 1/r < 0 • Angles: positive measured counterclockwise θ > 0 θ < 0 • Heights: positive above the axis Introduction to CODE V Training, “Optics 101,” Slide 1-4 Introduction to CODE V Optics 101 • 1-2 Copyright © 2009 Optical Research Associates Light from Physics 102 • Light travels in straight lines (homogeneous media) • Snell’s Law: n sin θ = n’ sin θ’ • Paraxial approximation: –Small angles:sin θ~ tan θ ~ θ; and cos θ ~ 1 – Optical surfaces represented by tangent plane at vertex • Ignore sag in computing ray height • Thickness is always center thickness – Power of a spherical refracting surface: 1/f = φ = (n’-n)*c -

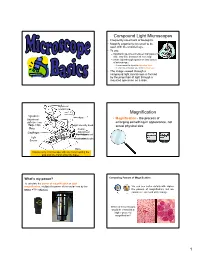

Compound Light Microscopes Magnification

Compound Light Microscopes • Frequently used tools of biologists. • Magnify organisms too small to be seen with the unaided eye. • To use: – Sandwich specimen between transparent slide and thin, transparent coverslip. – Shine light through specimen into lenses of microscope. • Lens closest to object is objective lens. • Lens closest to your eye is the ocular lens. • The image viewed through a compound light microscope is formed by the projection of light through a mounted specimen on a slide. Eyepiece/ ocular lens Magnification Nosepiece Arm Objectives/ • Magnification - the process of objective lens enlarging something in appearance, not Stage Clips Light intensity knob actual physical size. Stage Coarse DiaphragmDiaphragm Adjustment Fine Adjustment Light Positioning knobs Source Base Always carry a microscope with one hand holding the arm and one hand under the base. What’s my power? Comparing Powers of Magnification To calculate the power of magnification or total magnification, multiply the power of the ocular lens by the We can see better details with higher power of the objective. the powers of magnification, but we cannot see as much of the image. Which of these images would be viewed at a higher power of magnification? 1 Resolution Limit of resolution • Resolution - the shortest distance • As magnifying power increases, we see between two points more detail. on a specimen that • There is a point where we can see no can still be more detail is the limit of resolution. distinguished as – Beyond the limit of resolution, objects get two points. blurry and detail is lost. – Use electron microscopes to reveal detail beyond the limit of resolution of a compound light microscope! Proper handling technique Field of view 1. -

Depth of Field PDF Only

Depth of Field for Digital Images Robin D. Myers Better Light, Inc. In the days before digital images, before the advent of roll film, photography was accomplished with photosensitive emulsions spread on glass plates. After processing and drying the glass negative, it was contact printed onto photosensitive paper to produce the final print. The size of the final print was the same size as the negative. During this period some of the foundational work into the science of photography was performed. One of the concepts developed was the circle of confusion. Contact prints are usually small enough that they are normally viewed at a distance of approximately 250 millimeters (about 10 inches). At this distance the human eye can resolve a detail that occupies an angle of about 1 arc minute. The eye cannot see a difference between a blurred circle and a sharp edged circle that just fills this small angle at this viewing distance. The diameter of this circle is called the circle of confusion. Converting the diameter of this circle into a size measurement, we get about 0.1 millimeters. If we assume a standard print size of 8 by 10 inches (about 200 mm by 250 mm) and divide this by the circle of confusion then an 8x10 print would represent about 2000x2500 smallest discernible points. If these points are equated to their equivalence in digital pixels, then the resolution of a 8x10 print would be about 2000x2500 pixels or about 250 pixels per inch (100 pixels per centimeter). The circle of confusion used for 4x5 film has traditionally been that of a contact print viewed at the standard 250 mm viewing distance. -

Ernst Abbe 1840-1905: a Social Reformer

We all do not belong to ourselves Ernst Abbe 1840-1905: a Social Reformer Fritz Schulze, Canada Linda Nguyen, The Canadian Press, Wednesday, January 2014: TORONTO – By the time you finish your lunch on Thursday, Canada’s top paid CEO will have already earned (my italics!) the equivalent of your annual salary.* It is not unusual these days to read such or similar headlines. Each time I am reminded of the co-founder of the company I worked for all my active life. Those who know me, know that I worked for the world-renowned German optical company Carl Zeiss. I also have a fine collection of optical instruments, predominantly microscopes, among them quite a few Zeiss instruments. Carl Zeiss founded his business as a “mechanical atelier” in Jena in 1846 and his mathematical consultant, Ernst Abbe, a poorly paid lecturer at the University Jena, became his partner in 1866. That was the beginning of a comet-like rise of the young company. Ernst Abbe was born in Eisenach, Thuringia, on January 23, 1840, as the first child of a spinnmaster of a local textile mill.Till the beginning of the 50s each and every day the Lord made my father stood at his machines, 14, 15, 16 hours, from 5 o’clock in the morning till 7 o’clock in the evening during quiet periods, 16 hours from 4 o’clock in the morning till 8 o’clock in the evening during busy times, without any interruption, not even a lunch break. I myself as a small boy of 5 – 9 years brought him his lunch, alternately with my younger sister, and watched him as he gulped it down leaning on his machine or sitting on a wooden box, then handing me back the empty pail and immediately again tending his machines." Ernst Abbe remembered later. -

Sky & Telescope

S&T Test Report by Rod Mollise Meade’s 115-Millimeter ED Triplet This 4.5-inch apochromat packs a lot of bang for the buck. 115mm Series 6000 THIS IS A GREAT TIME to be in the ice and was eager to see how others market for a premium refracting tele- performed. So when I was approached ED Triplet APO scope. The price for high-quality refrac- about evaluating Meade’s 115mm Series U.S. Price: $1,899 tors has fallen dramatically in recent 6000 ED Triplet APO, I was certainly up meade.com years, and you can now purchase a for the task. 4- to-5-inch extra-low dispersion (ED) First impressions are important, and What We Like apochromatic (APO) telescope that’s when I unboxed the scope on the day Sharp, well-corrected optics almost entirely free of the false color it arrived, I lit up when I saw it. This is Color-free views that plagues achromats for a fraction of Attractive fi nish the cost commonly seen a decade ago. I’ve had a ball with my own recently q The Meade 115mm Series 6000 ED Triplet What We Don’t Like purchased apochromat after using APO ready for a night’s activity, shown with an optional 2-inch mirror diagonal. The scope Visual back locking almost nothing but Schmidt-Cassegrain also accepts fi nderscopes that attach using a system can be awkward telescopes for many years. However, I standardized dovetail system commonly found Focuser backlash still consider myself a refractor nov- on small refractors. -

Subwavelength Resolution Fourier Ptychography with Hemispherical Digital Condensers

Subwavelength resolution Fourier ptychography with hemispherical digital condensers AN PAN,1,2 YAN ZHANG,1,2 KAI WEN,1,3 MAOSEN LI,4 MEILING ZHOU,1,2 JUNWEI MIN,1 MING LEI,1 AND BAOLI YAO1,* 1State Key Laboratory of Transient Optics and Photonics, Xi’an Institute of Optics and Precision Mechanics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Xi’an 710119, China 2University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049, China 3College of Physics and Information Technology, Shaanxi Normal University, Xi’an 710071, China 4Xidian University, Xi’an 710071, China *[email protected] Abstract: Fourier ptychography (FP) is a promising computational imaging technique that overcomes the physical space-bandwidth product (SBP) limit of a conventional microscope by applying angular diversity illuminations. However, to date, the effective imaging numerical aperture (NA) achievable with a commercial LED board is still limited to the range of 0.3−0.7 with a 4×/0.1NA objective due to the constraint of planar geometry with weak illumination brightness and attenuated signal-to-noise ratio (SNR). Thus the highest achievable half-pitch resolution is usually constrained between 500−1000 nm, which cannot fulfill some needs of high-resolution biomedical imaging applications. Although it is possible to improve the resolution by using a higher magnification objective with larger NA instead of enlarging the illumination NA, the SBP is suppressed to some extent, making the FP technique less appealing, since the reduction of field-of-view (FOV) is much larger than the improvement of resolution in this FP platform. Herein, in this paper, we initially present a subwavelength resolution Fourier ptychography (SRFP) platform with a hemispherical digital condenser to provide high-angle programmable plane-wave illuminations of 0.95NA, attaining a 4×/0.1NA objective with the final effective imaging performance of 1.05NA at a half-pitch resolution of 244 nm with a wavelength of 465 nm across a wide FOV of 14.60 mm2, corresponding to an SBP of 245 megapixels. -

Depth of Focus (DOF)

Erect Image Depth of Focus (DOF) unit: mm Also known as ‘depth of field’, this is the distance (measured in the An image in which the orientations of left, right, top, bottom and direction of the optical axis) between the two planes which define the moving directions are the same as those of a workpiece on the limits of acceptable image sharpness when the microscope is focused workstage. PG on an object. As the numerical aperture (NA) increases, the depth of 46 focus becomes shallower, as shown by the expression below: λ DOF = λ = 0.55µm is often used as the reference wavelength 2·(NA)2 Field number (FN), real field of view, and monitor display magnification unit: mm Example: For an M Plan Apo 100X lens (NA = 0.7) The depth of focus of this objective is The observation range of the sample surface is determined by the diameter of the eyepiece’s field stop. The value of this diameter in 0.55µm = 0.6µm 2 x 0.72 millimeters is called the field number (FN). In contrast, the real field of view is the range on the workpiece surface when actually magnified and observed with the objective lens. Bright-field Illumination and Dark-field Illumination The real field of view can be calculated with the following formula: In brightfield illumination a full cone of light is focused by the objective on the specimen surface. This is the normal mode of viewing with an (1) The range of the workpiece that can be observed with the optical microscope. With darkfield illumination, the inner area of the microscope (diameter) light cone is blocked so that the surface is only illuminated by light FN of eyepiece Real field of view = from an oblique angle. -

22 Bull. Hist. Chem. 8 (1990)

22 Bull. Hist. Chem. 8 (1990) 15 nntn Cn r fr l 4 0 tllOt f th r h npntd nrpt ltd n th brr f th trl St f nnlvn n thr prt nd ntn ntl 1 At 1791 1 frn 7 p 17 AS nntn t h 3 At 179 brr Cpn f hldlph 8Gztt f th Untd Stt Wdnd 3 l 1793 h ntr nnnnt rprdd n W Ml "njn h Cht"Ch 1953 37-77 h pn pr dtd 1 l 179 nd nd b Gr Whntn th frt ptnt d n th Untd Stt S M ntr h rt US tnt" Ar rt Invnt hn 199 6(2 1- 19 ttrfld ttr fnjn h Arn hl- phl St l rntn 1951 pp 7 9 20h drl Gztt 1793 (20 Sptbr Qtd n Ml rfrn 1 1 W Ml rfrn 1 pp 7-75 William D. Williams is Professor of Chemistry at Harding r brt tr University, Searcy, Al? 72143. He collects and studies early American chemistry texts. Wyndham D. Miles. 24 Walker their British cultural heritage. To do this, they turned to the Avenue, Gaithersburg, MD 20877, is winner of the 1971 schools (3). This might explain why the Virginia assembly Dexter Award and is currently in the process of completing the took time in May, 1780 - during a period when their highest second volume of his biographical dictionary. "American priority was the threat of British invasion following the fall of Chemists and Chemical Engineers". Charleston - to charter the establishment of Transylvania Seminary, which would serve as a spearhead of learning in the wilderness (1). -

Bernhard Riemann 1826-1866

Modern Birkh~user Classics Many of the original research and survey monographs in pure and applied mathematics published by Birkh~iuser in recent decades have been groundbreaking and have come to be regarded as foun- dational to the subject. Through the MBC Series, a select number of these modern classics, entirely uncorrected, are being re-released in paperback (and as eBooks) to ensure that these treasures remain ac- cessible to new generations of students, scholars, and researchers. BERNHARD RIEMANN (1826-1866) Bernhard R~emanno 1826 1866 Turning Points in the Conception of Mathematics Detlef Laugwitz Translated by Abe Shenitzer With the Editorial Assistance of the Author, Hardy Grant, and Sarah Shenitzer Reprint of the 1999 Edition Birkh~iuser Boston 9Basel 9Berlin Abe Shendtzer (translator) Detlef Laugwitz (Deceased) Department of Mathematics Department of Mathematics and Statistics Technische Hochschule York University Darmstadt D-64289 Toronto, Ontario M3J 1P3 Gernmany Canada Originally published as a monograph ISBN-13:978-0-8176-4776-6 e-ISBN-13:978-0-8176-4777-3 DOI: 10.1007/978-0-8176-4777-3 Library of Congress Control Number: 2007940671 Mathematics Subject Classification (2000): 01Axx, 00A30, 03A05, 51-03, 14C40 9 Birkh~iuser Boston All rights reserved. This work may not be translated or copied in whole or in part without the writ- ten permission of the publisher (Birkh~user Boston, c/o Springer Science+Business Media LLC, 233 Spring Street, New York, NY 10013, USA), except for brief excerpts in connection with reviews or scholarly analysis. Use in connection with any form of information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter de- veloped is forbidden. -

Introduction to Light Microscopy

Introduction to light microscopy A CAMDU training course Claire Mitchell, Imaging specialist, L1.01, 08-10-2018 Contents 1.Introduction to light microscopy 2.Different types of microscope 3.Fluorescence techniques 4.Acquiring quantitative microscopy data 1. Introduction to light microscopy 1.1 Light and its properties 1.2 A simple microscope 1.3 The resolution limit 1.1 Light and its properties 1.1.1 What is light? An electromagnetic wave A massless particle AND γ commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:EM-Wave.gif www.particlezoo.net 1.1.2 Properties of waves Light waves are transverse waves – they oscillate orthogonally to the direction of propagation Important properties of light: wavelength, frequency, speed, amplitude, phase, polarisation upload.wikimedia.org 1.1.3 The electromagnetic spectrum 퐸푝ℎ표푡표푛 = ℎν 푐 = λν 퐸푝ℎ표푡표푛 = photon energy ℎ = Planck’s constant ν = frequency 푐 = speed of light λ = wavelength pion.cz/en/article/electromagnetic-spectrum 1.1.4 Refraction Light bends when it encounters a change in refractive index e.g. air to glass www.thetastesf.com files.askiitians.com hyperphysics.phy-astr.gsu.edu/hbase/Sound/imgsou/refr.gif 1.1.5 Diffraction Light waves spread out when they encounter an aperture. electron6.phys.utk.edu/light/1/Diffraction.htm The smaller the aperture, the larger the spread of light. 1.1.6 Interference When waves overlap, they add together in a process called interference. peak + peak = 2 x peak constructive trough + trough = 2 x trough peak + trough = 0 destructive www.acs.psu.edu/drussell/demos/superposition/superposition.html 1.2 A simple microscope 1.2.1 Using lenses for refraction 1 1 1 푣 = + 푚 = physicsclassroom.com 푓 푢 푣 푢 cdn.education.com/files/ Light bends as it encounters each air/glass interface of a lens.