Encke's Minima and Encke's Division in Saturn's A-Ring

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Galileo and the Telescope

Galileo and the Telescope A Discussion of Galileo Galilei and the Beginning of Modern Observational Astronomy ___________________________ Billy Teets, Ph.D. Acting Director and Outreach Astronomer, Vanderbilt University Dyer Observatory Tuesday, October 20, 2020 Image Credit: Giuseppe Bertini General Outline • Telescopes/Galileo’s Telescopes • Observations of the Moon • Observations of Jupiter • Observations of Other Planets • The Milky Way • Sunspots Brief History of the Telescope – Hans Lippershey • Dutch Spectacle Maker • Invention credited to Hans Lippershey (c. 1608 - refracting telescope) • Late 1608 – Dutch gov’t: “ a device by means of which all things at a very great distance can be seen as if they were nearby” • Is said he observed two children playing with lenses • Patent not awarded Image Source: Wikipedia Galileo and the Telescope • Created his own – 3x magnification. • Similar to what was peddled in Europe. • Learned magnification depended on the ratio of lens focal lengths. • Had to learn to grind his own lenses. Image Source: Britannica.com Image Source: Wikipedia Refracting Telescopes Bend Light Refracting Telescopes Chromatic Aberration Chromatic aberration limits ability to distinguish details Dealing with Chromatic Aberration - Stop Down Aperture Galileo used cardboard rings to limit aperture – Results were dimmer views but less chromatic aberration Galileo and the Telescope • Created his own (3x, 8-9x, 20x, etc.) • Noted by many for its military advantages August 1609 Galileo and the Telescope • First observed the -

Imaginative Geographies of Mars: the Science and Significance of the Red Planet, 1877 - 1910

Copyright by Kristina Maria Doyle Lane 2006 The Dissertation Committee for Kristina Maria Doyle Lane Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: IMAGINATIVE GEOGRAPHIES OF MARS: THE SCIENCE AND SIGNIFICANCE OF THE RED PLANET, 1877 - 1910 Committee: Ian R. Manners, Supervisor Kelley A. Crews-Meyer Diana K. Davis Roger Hart Steven D. Hoelscher Imaginative Geographies of Mars: The Science and Significance of the Red Planet, 1877 - 1910 by Kristina Maria Doyle Lane, B.A.; M.S.C.R.P. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin August 2006 Dedication This dissertation is dedicated to Magdalena Maria Kost, who probably never would have understood why it had to be written and certainly would not have wanted to read it, but who would have been very proud nonetheless. Acknowledgments This dissertation would have been impossible without the assistance of many extremely capable and accommodating professionals. For patiently guiding me in the early research phases and then responding to countless followup email messages, I would like to thank Antoinette Beiser and Marty Hecht of the Lowell Observatory Library and Archives at Flagstaff. For introducing me to the many treasures held deep underground in our nation’s capital, I would like to thank Pam VanEe and Ed Redmond of the Geography and Map Division of the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C. For welcoming me during two brief but productive visits to the most beautiful library I have seen, I thank Brenda Corbin and Gregory Shelton of the U.S. -

Eclipse Science Results: Past and Present

The Last Total Solar Eclipse of the Mil lennium in Turkey ASP Conference Series Vol W Livingston and A Ozgu c eds Eclipse Science Results Past and Present W Livingston National Solar Observatory NOAO PO Box Tucson AZ USA S Koutchmy Institut dAstrophysique de ParisCNRS Bis Boulevard Arago F Paris France Abstract We review the signicant advances that havebeenachieved by eclipse exp eriments First we note the anomaly that the corona was not even seen until relatively mo dern times Beginning in whitelight WL photographs suggested structures that must have b een dominated by magnetic elds This led to the disco very of surface magnetism in sunsp ots by Hale in the rst detection of cosmic magnetism Deli cate direct photographic observations conrmed the b ending of starlight near the eclipsed Sun as predicted by Einsteins General Theory of Rela tivity Chromospheric ash sp ectra indicated that the outer layer of the Sun was much hotter than the underlying photosphere leading to non lo cal thermo dynamic equilibrium concepts and the idea of various me chanical and wave pro cesses to maintain it Decades have been devoted to understanding the corona Discovery of its million degree plus tem p erature and guring howto heat it how co ol prominences can coexist within it all are topics to which eclipse observations havecontributed Totality without a Corona Eclipses have b een chronicled for o ver years but the corona escap ed b eing noticed until mo dern times The single exception Leonis Deaconis in AD mentions a certain dull and feeble glow -

The Comet's Tale, and Therefore the Object As a Whole Would the Section Director Nick James Highlighted Have a Low Surface Brightness

1 Diebold Schilling, Disaster in connection with two comets sighted in 1456, Lucerne Chronicle, 1513 (Wikimedia Commons) THE COMET’S TALE Comet Section – British Astronomical Association Journal – Number 38 2019 June britastro.org/comet Evolution of the comet C/2016 R2 (PANSTARRS) along a total of ten days on January 2018. Composition of pictures taken with a zoom lens from Teide Observatory in Canary Islands. J.J Chambó Bris 2 Table of Contents Contents Author Page 1 Director’s Welcome Nick James 3 Section Director 2 Melvyn Taylor’s Alex Pratt 6 Observations of Comet C/1995 01 (Hale-Bopp) 3 The Enigma of Neil Norman 9 Comet Encke 4 Setting up the David Swan 14 C*Hyperstar for Imaging Comets 5 Comet Software Owen Brazell 19 6 Pro-Am José Joaquín Chambó Bris 25 Astrophotography of Comets 7 Elizabeth Roemer: A Denis Buczynski 28 Consummate Comet Section Secretary Observer 8 Historical Cometary Amar A Sharma 37 Observations in India: Part 2 – Mughal Empire 16th and 17th Century 9 Dr Reginald Denis Buczynski 42 Waterfield and His Section Secretary Medals 10 Contacts 45 Picture Gallery Please note that copyright 46 of all images belongs with the Observer 3 1 From the Director – Nick James I hope you enjoy reading this issue of the We have had a couple of relatively bright Comet’s Tale. Many thanks to Janice but diffuse comets through the winter and McClean for editing this issue and to Denis there are plenty of images of Buczynski for soliciting contributions. 46P/Wirtanen and C/2018 Y1 (Iwamoto) Thanks also to the section committee for in our archive. -

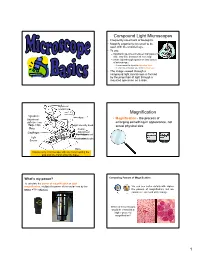

Compound Light Microscopes Magnification

Compound Light Microscopes • Frequently used tools of biologists. • Magnify organisms too small to be seen with the unaided eye. • To use: – Sandwich specimen between transparent slide and thin, transparent coverslip. – Shine light through specimen into lenses of microscope. • Lens closest to object is objective lens. • Lens closest to your eye is the ocular lens. • The image viewed through a compound light microscope is formed by the projection of light through a mounted specimen on a slide. Eyepiece/ ocular lens Magnification Nosepiece Arm Objectives/ • Magnification - the process of objective lens enlarging something in appearance, not Stage Clips Light intensity knob actual physical size. Stage Coarse DiaphragmDiaphragm Adjustment Fine Adjustment Light Positioning knobs Source Base Always carry a microscope with one hand holding the arm and one hand under the base. What’s my power? Comparing Powers of Magnification To calculate the power of magnification or total magnification, multiply the power of the ocular lens by the We can see better details with higher power of the objective. the powers of magnification, but we cannot see as much of the image. Which of these images would be viewed at a higher power of magnification? 1 Resolution Limit of resolution • Resolution - the shortest distance • As magnifying power increases, we see between two points more detail. on a specimen that • There is a point where we can see no can still be more detail is the limit of resolution. distinguished as – Beyond the limit of resolution, objects get two points. blurry and detail is lost. – Use electron microscopes to reveal detail beyond the limit of resolution of a compound light microscope! Proper handling technique Field of view 1. -

EPSC2015-913, 2015 European Planetary Science Congress 2015 Eeuropeapn Planetarsy Science Ccongress C Author(S) 2015

EPSC Abstracts Vol. 10, EPSC2015-913, 2015 European Planetary Science Congress 2015 EEuropeaPn PlanetarSy Science CCongress c Author(s) 2015 The “Station de Planétologie des Pyrénées” (S2P), a collaborative science program in the course of a long history at Pic du Midi observatory. F. Colas (1), A. Klotz (2), F. Vachier (1), M. Birlan (1), B. Sicardy (3), J. Lecacheux (3), M. Antuna (6), R. Behrend (4), C. Birnbaum (6), G. Blanchard (6), C. Buil (4,5), J. Caquel (6), M. Castets (5), C. Cavadore (4), B. Christophe (6), F. Cochard (4), J.L. Dauvergne (6), F. Deladerriere (6), M. Delcroix (6), V. Denoux (4), J.B. DeVanssay (6), P. Devechere (6), P. Dupouy (5), E. Frappa (6), S. Fauvaud (5), B. Gaillard (6), F. Jabet (6), M. Lavayssiere (6), T. Legault (6), A. Leroy (5), A. Maury (6), M. Meunier (6), C. Pellier (6), C. Rinner (4), E. Rolland (6), O. Stenuit (6), I. Testar (6), P. Thierry (4), O. Thizy (4), B. Tregon (5), F. Vaissiere (4), S. Vauclair (6), C. Viladrich (6), C. Angeli (6), J.E. Arlot (1), M. Assafin (28), D. Bancelin (1), D. Baratoux (29), N. Barrado-Izagirre (8), M.A. Barucci (3), L. Beauvalet (9), P. Bendjoya (13), J. Berthier (1), N. Biver (3), D. Bockelee-Morvan (3), D. Berard (3), S. Bouley (10), S. Bouquillon (9), P. Bourget (11), F. Bragas- Ribas (7), J. Camargo (7), B. Carry (1), S. Chevrel (2), M; Chevreton, (3), P. Colom (3), J. Crovisier (3), J. Demars (1), R. Despiau (2), P. Descamps (1), N. Dolez (2), A. -

The Icha Newsletter Newsletter of the Inter-Union Commission For

International Astronomical Union International Union of the History and Philosophy of Science DHS/IUHPS ______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ THE ICHA NEWSLETTER NEWSLETTER OF THE INTER-UNION COMMISSION FOR HISTORY OF ASTRONOMY* ____________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________ No. 11 – January 2011 SUMMARY A. Archaeoastronomy and Ethnoastronomy: Building Bridges between Cultures – IAU Symposium S278 Report by C. Ruggles ..................................................... 1 B. Historical Observatory building to be restored by A. Simpson …..…..…...… 5 C. History of Astronomy in India by B. S. Shylaja ……………………………….. 6 D. Journals and Publications: - Acta Historica Astronomiae by Hilmar W. Duerbeck ................................ 8 Books 2008/2011 ............................................................................................. 9 Some research papers by C41/ICHA members - 2009/2010 ........................... 9 E. News - Exhibitions on the Antikythera Mechanism by E. Nicolaidis ……………. 10 - XII Universeum Meeting by M. Lourenço, S. Talas, R. Wittje ………….. 10 - XXX Scientific Instrument Symposium by K.Gaulke ..………………… 12 F. ICHA Member News by B. Corbin ………………………………………… 13 * The ICHA includes IAU Commission 41 (History of Astronomy), all of whose members are, ipso facto, members of the ICHA. ________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ -

Lab 11: the Compound Microscope

OPTI 202L - Geometrical and Instrumental Optics Lab 9-1 LAB 9: THE COMPOUND MICROSCOPE The microscope is a widely used optical instrument. In its simplest form, it consists of two lenses Fig. 9.1. An objective forms a real inverted image of an object, which is a finite distance in front of the lens. This image in turn becomes the object for the ocular, or eyepiece. The eyepiece forms the final image which is virtual, and magnified. The overall magnification is the product of the individual magnifications of the objective and the eyepiece. Figure 9.1. Images in a compound microscope. To illustrate the concept, use a 38 mm focal length lens (KPX079) as the objective, and a 50 mm focal length lens (KBX052) as the eyepiece. Set them up on the optical rail and adjust them until you see an inverted and magnified image of an illuminated object. Note the intermediate real image by inserting a piece of paper between the lenses. Q1 ● Can you demonstrate the final image by holding a piece of paper behind the eyepiece? Why or why not? The eyepiece functions as a magnifying glass, or simple magnifier. In effect, your eye looks into the eyepiece, and in turn the eyepiece looks into the optical system--be it a compound microscope, a spotting scope, telescope, or binocular. In all cases, the eyepiece doesn't view an actual object, but rather some intermediate image formed by the "front" part of the optical system. With telescopes, this intermediate image may be real or virtual. With the compound microscope, this intermediate image is real, formed by the objective lens. -

How We Found About COMETS

How we found about COMETS Isaac Asimov Isaac Asimov is a master storyteller, one of the world’s greatest writers of science fiction. He is also a noted expert on the history of scientific development, with a gift for explaining the wonders of science to non- experts, both young and old. These stories are science-facts, but just as readable as science fiction.Before we found out about comets, the superstitious thought they were signs of bad times ahead. The ancient Greeks called comets “aster kometes” meaning hairy stars. Even to the modern day astronomer, these nomads of the solar system remain a puzzle. Isaac Asimov makes a difficult subject understandable and enjoyable to read. 1. The hairy stars Human beings have been watching the sky at night for many thousands of years because it is so beautiful. For one thing, there are thousands of stars scattered over the sky, some brighter than others. These stars make a pattern that is the same night after night and that slowly turns in a smooth and regular way. There is the Moon, which does not seem a mere dot of light like the stars, but a larger body. Sometimes it is a perfect circle of light but at other times it is a different shape—a half circle or a curved crescent. It moves against the stars from night to night. One midnight, it could be near a particular star, and the next midnight, quite far away from that star. There are also visible 5 star-like objects that are brighter than the stars. -

The First Measurement of the Deflection of the Vertical in Longitude

Eur. Phys. J. H. DOI: 10.1140/epjh/e2014-40055-2 The first measurement of the deflection of the vertical in longitude The figure of the earth in the early 19th century Andreas Schrimpfa Philipps-Universit¨atMarburg, Fachbereich Physik, Renthof 5, D-35032 Marburg, Germany Abstract. During the summer of 1837 Christian Ludwig Gerling, a for- mer student of Carl Friedrich Gauß’s, organized the world wide first de- termination of the deflection of the vertical in longitude. From a mobile observatory at the Frauenberg near Marburg (Hesse) he measured the astronomical longitude difference between C.F. Gauß’s observatory at G¨ottingenand F.G.B. Nicolai's observatory at Mannheim within an er- ror of 000: 4. To achieve this precision he first used a series of light signals for synchronizing the observatory clocks and, second, he very carefully corrected for the varying reaction time of the observers. By comparing these astronomical results with the geodetic{determined longitude dif- ferences he had recently measured for the triangulation of Kurhessen, he was able to extract a combined value of the deflection of the vertical in longitude of G¨ottingenand Mannheim. His results closely agree with modern vertical deflection data. 1 Introduction The discussion about the figure of the earth and its determination was an open ques- tion for almost two thousand years, the sciences involved were geodesy, geography and astronomy. Without precise instruments the everyday experience suggested a flat, plane world, although ideas of a spherically shaped earth were known and ac- cepted even in the ancient world. Assuming that the easily observable daily motion of the stars is due to the rotation of the earth, the rotational axis can be used to define a celestial sphere; a coordinate system, where the stars' position is given by two angles. -

Staircase of Vienna Observatory (Institut Für Astronomie Der Universität Wien)

Figure 15.1: Staircase of Vienna Observatory (Institut für Astronomie der Universität Wien) 142 15. The University Observatory Vienna Anneliese Schnell (Vienna, Austria) 15.1 Introduction should prefer non-German instrument makers (E. Weiss 1873). In spring of 2008 the new Vienna Observatory was th commemorating its 125 anniversary, it was officially During a couple of years Vienna Observatory was edit- opened by Emperor Franz Joseph in 1883. Regular ob- ing an astronomical calendar. In the 1874 edition K. L. servations had started in 1880. Viennese astronomers Littrow wrote a contribution about the new observatory had planned that observatory for a long time. Already th in which he defined the instrumental needs: Karl von Littrow’s father had plans early in the 19 “für Topographie des Himmels ein mächtiges parallakti- century (at that time according to a letter from Joseph sches Fernrohr, ein dioptrisches Instrument von 25 Zoll Johann Littrow to Gauß from December 1, 1823 the Öffnung. Da sich aber ein Werkzeug von solcher Grö- observatory of Turku was taken as model) (Reich 2008), ße für laufende Beobachtungen (Ortsbestimmung neu- but it lasted until 1867 when it was decided to build a er Planeten und Kometen, fortgesetzte Doppelsternmes- new main building of the university of Vienna and also sungen, etc.) nicht eignet, ein zweites, kleineres, daher a new observatory. Viennese astronomers at that time leichter zu handhabendes, aber zur Beobachtung licht- had an excellent training in mathematics, they mostly schwacher Objekte immer noch hinreichendes Teleskop worked on positional astronomy and celestial mechanics. von etwa 10 Zoll Öffnung, und ein Meridiankreis er- They believed in F. -

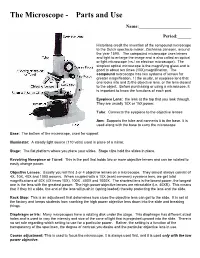

The Microscope Parts And

The Microscope Parts and Use Name:_______________________ Period:______ Historians credit the invention of the compound microscope to the Dutch spectacle maker, Zacharias Janssen, around the year 1590. The compound microscope uses lenses and light to enlarge the image and is also called an optical or light microscope (vs./ an electron microscope). The simplest optical microscope is the magnifying glass and is good to about ten times (10X) magnification. The compound microscope has two systems of lenses for greater magnification, 1) the ocular, or eyepiece lens that one looks into and 2) the objective lens, or the lens closest to the object. Before purchasing or using a microscope, it is important to know the functions of each part. Eyepiece Lens: the lens at the top that you look through. They are usually 10X or 15X power. Tube: Connects the eyepiece to the objective lenses Arm: Supports the tube and connects it to the base. It is used along with the base to carry the microscope Base: The bottom of the microscope, used for support Illuminator: A steady light source (110 volts) used in place of a mirror. Stage: The flat platform where you place your slides. Stage clips hold the slides in place. Revolving Nosepiece or Turret: This is the part that holds two or more objective lenses and can be rotated to easily change power. Objective Lenses: Usually you will find 3 or 4 objective lenses on a microscope. They almost always consist of 4X, 10X, 40X and 100X powers. When coupled with a 10X (most common) eyepiece lens, we get total magnifications of 40X (4X times 10X), 100X , 400X and 1000X.