Observation of Venus and Mercury Transits from the Pic-Du-Midi Observatory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Eclipse Science Results: Past and Present

The Last Total Solar Eclipse of the Mil lennium in Turkey ASP Conference Series Vol W Livingston and A Ozgu c eds Eclipse Science Results Past and Present W Livingston National Solar Observatory NOAO PO Box Tucson AZ USA S Koutchmy Institut dAstrophysique de ParisCNRS Bis Boulevard Arago F Paris France Abstract We review the signicant advances that havebeenachieved by eclipse exp eriments First we note the anomaly that the corona was not even seen until relatively mo dern times Beginning in whitelight WL photographs suggested structures that must have b een dominated by magnetic elds This led to the disco very of surface magnetism in sunsp ots by Hale in the rst detection of cosmic magnetism Deli cate direct photographic observations conrmed the b ending of starlight near the eclipsed Sun as predicted by Einsteins General Theory of Rela tivity Chromospheric ash sp ectra indicated that the outer layer of the Sun was much hotter than the underlying photosphere leading to non lo cal thermo dynamic equilibrium concepts and the idea of various me chanical and wave pro cesses to maintain it Decades have been devoted to understanding the corona Discovery of its million degree plus tem p erature and guring howto heat it how co ol prominences can coexist within it all are topics to which eclipse observations havecontributed Totality without a Corona Eclipses have b een chronicled for o ver years but the corona escap ed b eing noticed until mo dern times The single exception Leonis Deaconis in AD mentions a certain dull and feeble glow -

EPSC2015-913, 2015 European Planetary Science Congress 2015 Eeuropeapn Planetarsy Science Ccongress C Author(S) 2015

EPSC Abstracts Vol. 10, EPSC2015-913, 2015 European Planetary Science Congress 2015 EEuropeaPn PlanetarSy Science CCongress c Author(s) 2015 The “Station de Planétologie des Pyrénées” (S2P), a collaborative science program in the course of a long history at Pic du Midi observatory. F. Colas (1), A. Klotz (2), F. Vachier (1), M. Birlan (1), B. Sicardy (3), J. Lecacheux (3), M. Antuna (6), R. Behrend (4), C. Birnbaum (6), G. Blanchard (6), C. Buil (4,5), J. Caquel (6), M. Castets (5), C. Cavadore (4), B. Christophe (6), F. Cochard (4), J.L. Dauvergne (6), F. Deladerriere (6), M. Delcroix (6), V. Denoux (4), J.B. DeVanssay (6), P. Devechere (6), P. Dupouy (5), E. Frappa (6), S. Fauvaud (5), B. Gaillard (6), F. Jabet (6), M. Lavayssiere (6), T. Legault (6), A. Leroy (5), A. Maury (6), M. Meunier (6), C. Pellier (6), C. Rinner (4), E. Rolland (6), O. Stenuit (6), I. Testar (6), P. Thierry (4), O. Thizy (4), B. Tregon (5), F. Vaissiere (4), S. Vauclair (6), C. Viladrich (6), C. Angeli (6), J.E. Arlot (1), M. Assafin (28), D. Bancelin (1), D. Baratoux (29), N. Barrado-Izagirre (8), M.A. Barucci (3), L. Beauvalet (9), P. Bendjoya (13), J. Berthier (1), N. Biver (3), D. Bockelee-Morvan (3), D. Berard (3), S. Bouley (10), S. Bouquillon (9), P. Bourget (11), F. Bragas- Ribas (7), J. Camargo (7), B. Carry (1), S. Chevrel (2), M; Chevreton, (3), P. Colom (3), J. Crovisier (3), J. Demars (1), R. Despiau (2), P. Descamps (1), N. Dolez (2), A. -

Patrimoines Du Sud, 12 | 2020 Comment Évaluer L’Importance Patrimoniale D’Un Lieu Unique Et Complexe Grâce

Patrimoines du Sud 12 | 2020 Patrimoines et numérique : un état de la recherche et des expérimentations Comment évaluer l’importance patrimoniale d’un lieu unique et complexe grâce au numérique ? L’exemple du Pic du Midi How to assess the heritage significance of a unique and complex site using digital tools? The example of the Pic du Midi Loïc Jeanson, Michel Cotte, Florent Laroche et Léa Bland-Dupré Édition électronique URL : http://journals.openedition.org/pds/4837 DOI : 10.4000/pds.4837 ISSN : 2494-2782 Éditeur Conseil régional Occitanie Référence électronique Loïc Jeanson, Michel Cotte, Florent Laroche et Léa Bland-Dupré, « Comment évaluer l’importance patrimoniale d’un lieu unique et complexe grâce au numérique ? L’exemple du Pic du Midi », Patrimoines du Sud [En ligne], 12 | 2020, mis en ligne le 01 septembre 2020, consulté le 02 septembre 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/pds/4837 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/pds.4837 Ce document a été généré automatiquement le 2 septembre 2020. La revue Patrimoines du Sud est mise à disposition selon les termes de la Licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas d'Utilisation Commerciale - Pas de Modification 4.0 International. Comment évaluer l’importance patrimoniale d’un lieu unique et complexe grâce ... 1 Comment évaluer l’importance patrimoniale d’un lieu unique et complexe grâce au numérique ? L’exemple du Pic du Midi How to assess the heritage significance of a unique and complex site using digital tools? The example of the Pic du Midi Loïc Jeanson, Michel Cotte, Florent Laroche et Léa Bland-Dupré Introduction 1 Depuis Tarbes, le Pic du Midi semble impossible à éviter. -

February 2014 the Newsletter of the Barnard-Seyfert Astronomical Society

February TheECLIPSE 2014 The Newsletter of the Barnard-Seyfert Astronomical Society From the President Next Membership Meeting: February 19, 2014, 7:30 pm Cumberland Valley Professionals vs. amateurs… the distinctions have Girl Scout Council Building blurred over the years in different ways. There was 4522 Granny White Pike a time when mere money could get you the gear to have a professional observatory. Many large Program Topic: telescopes were built with private funds by Joshua Emery - interested individuals… think of William Hershel and the “Don Quixote” object (details on page 5) Percival Lowell. Then amateurs were pushed aside by large scale photography and the truly large telescopes that needed institutions to care for and run them… like the Mt. Wilson and Mt. Palomar observatories. Expensive ccd cameras, exotic cooling, the computing power needed even after In this Issue: glass plates were replaced put meaningful observations out of reach of amateurs. Then with President’s Message 1 the advent of the personal computer and digital Observing Highlights 2 cameras, the playing field was leveled by computers that anyone could own, low noise digital Happy Birthday, cameras and powerful software. Bernard Ferdinand Lyot by Robin Byrne 3Today, you can take the hobby or second life in astronomy as far as you wish, in partnership with Board Meeting Minutes January 8, 2014 6professionals. On any given clear night, enthusiasts around the world are recording not just pretty Membership Meeting Minutes pictures, but data. Our sheer numbers allow us to January 15, 2013 9look at things in depth and at a frequency not possible if we depended just on the large research Membership Information 10 telescopes. -

Photométrie Et Astrométrie Des Satellites De Jupiter : Application À La Campagne De Phénomènes Mutuels 2015 Eléonore Saquet

Photométrie et Astrométrie des Satellites de Jupiter : application à la campagne de phénomènes mutuels 2015 Eléonore Saquet To cite this version: Eléonore Saquet. Photométrie et Astrométrie des Satellites de Jupiter : application à la campagne de phénomènes mutuels 2015. Astrophysique [astro-ph]. Université Paris sciences et lettres, 2017. Français. NNT : 2017PSLEO013. tel-01887821 HAL Id: tel-01887821 https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-01887821 Submitted on 4 Oct 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. A` mes parents, qui ont rendu possible le rˆeve d’une petite fille. T´elescope T1M du Pic du Midi. Cr´edit : St´ephane Vetter. Remerciements Ce m´emoire conclue mon travail de th`ese r´ealis´e`al’Institut de M´ecanique C´eleste et de Calculs des Eph´em´erides. Il n’aurait pas ´et´epossible sans l’appui d’un certain nombre de personnes, auxquelles je tiens `aexprimer ma sinc`ere gratitude. Je tiens tout d’abord `aremercier mes deux directeurs de th`ese Vincent Robert et Jean-Eudes Arlot de m’avoir propos´ece sujet puis de m’avoir encadr´ee pendant ces trois ann´ees. -

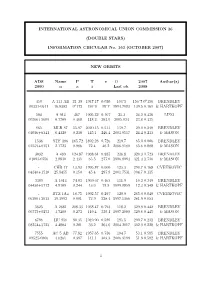

CIRCULAR No. 163 (OCTOBER 2007)

INTERNATIONAL ASTRONOMICAL UNION COMMISSION 26 (DOUBLE STARS) INFORMATION CIRCULAR No. 163 (OCTOBER 2007) NEW ORBITS ADS Name P T e (2000) 2007 Author(s) ®2000± n a i ! Last ob. 2008 450 A 111 AB 21y38 1947.17 0.020 104±5 156±7 000156 BRENDLEY 00321-0511 16.8382 000172 150±0 18±7 1994.7083 139.5 0.161 & HARTKOPF 504 A 914 467. 1905.32 0.107 35.3 24.2 0.436 LING 00366+5609 0.7709 0.468 118.2 291.9 2005.034 23.8 0.435 865 MLR 87 55.97 2020.45 0.513 139.7 29.0 0.240 BRENDLEY 01036+6341 6.4320 0.238 145.1 246.4 2003.9517 24.4 0.233 & MASON 1538 STF 186 165.72 1892.28 0.726 219.7 65.0 0.906 BRENDLEY 01559+0151 2.1723 0.986 72.4 40.2 2006.9180 65.6 0.888 & MASON 3032 A 469 124.87 1968.61 0.885 236.8 320.3 1.723 BRENDLEY 04093-0756 2.8830 2.435 65.5 277.0 1996.8984 321.4 1.736 & MASON - CHR 17 13.93 1995.87 0.600 125.3 290.7 0.168 CVETKOVIC 04340+1510 25.8455 0.150 45.4 297.9 2001.7531 304.7 0.135 3389 A 1014 74.83 1969.67 0.465 111.9 10.2 0.349 BRENDLEY 04430+5712 4.8109 0.244 13.0 78.8 1999.8859 12.3 0.348 & HARTKOPF - BTZ 1Aa 18.75 1992.57 0.297 120.9 265.0 0.040 CVETKOVIC 06290+2013 19.1992 0.081 72.9 228.4 1997.1366 281.9 0.053 5625 A 2681 208.33 1938.47 0.793 118.2 329.9 0.442 BRENDLEY 06575+0253 1.7280 0.273 119.4 339.1 1997.2000 329.6 0.445 & MASON 6796 HU 856 80.35 1949.90 0.589 185.5 299.7 0.231 BRENDLEY 08254+3723 4.4804 0.201 36.2 263.6 2004.2017 302.0 0.228 & HARTKOPF 7555 AC 5 AB 77.82 1957.65 0.736 194.7 53.1 0.585 BRENDLEY 09525-0806 4.6261 0.397 141.1 303.3 2006.3199 51.9 0.582 & HARTKOPF 1 NEW ORBITS (continuation) ADS Name P T e (2000) 2007 Author(s) ®2000± n a i ! Last ob. -

Tourmalet & Cycling's Greatest Challenges

Tourmalet & Cycling's Greatest Challenges - The Easier Way The peloton of the Tour de France has no time to enjoy the beautiful valleys and mountains of the central Pyrenees, or its authentic villages, great places to stay, and interesting regional cuisine. You will share their cycling challenges with the not insignificant help of e-bikes and travelling at your own pace, then be able to relax each evening in a way they can only dream of. If you love cycling and you love a challenge, but are not superhuman, this is the holiday for you - and one you will remember for all the best reasons. 7 nights - 6 days e-bike cycling Minimum required 1 From point to point With luggage transportation Self-guided Code : FP9PUTF The plus points • The major climbs and cols of the Tour de France • Cycling made easier - and much more enjoyable - thanks to electric bikes • An independent holiday - cycle at your own pace • Good quality, comfortable accommodation - and good meals too FP9PUTF Last update 29/12/2020 1 / 13 Before departure, please check that you have an updated fact sheet. FP9PUTF Last update 29/12/2020 2 / 13 The Tour de France's days in the Pyrenees are the most challenging cycling in the world. Now imagine you breezing up the Col du Tourmalet with a big grin on your face as you reach the summit of the Col d'Aubisque. You can now enjoy the most interesting and famous sections of the Tour de France route with the help of an electric bike - and Purely Pyrenees, the leading walking and cycling tour operator in the Pyrenees. -

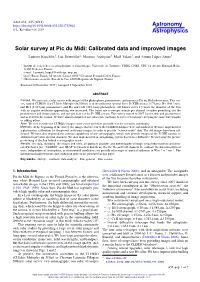

Solar Survey at Pic Du Midi: Calibrated Data and Improved Images Laurent Koechlin1, Luc Dettwiller2, Maurice Audejean3, Maël Valais1, and Arturo López Ariste1

A&A 631, A55 (2019) Astronomy https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/201732504 & c L. Koechlin et al. 2019 Astrophysics Solar survey at Pic du Midi: Calibrated data and improved images Laurent Koechlin1, Luc Dettwiller2, Maurice Audejean3, Maël Valais1, and Arturo López Ariste1 1 Institut de recherches en astrophysique et planétologie, Université de Toulouse, CNRS, CNES, UPS, 14 Avenue Edouard Belin, 31400 Toulouse, France e-mail: [email protected] 2 Lycée Blaise Pascal, 36 Avenue Carnot, 63037 Clermont-Ferrand Cedex, France 3 Observateurs associés, Rue de la Cau, 65200 Bagnères de Bigorre, France Received 20 December 2017 / Accepted 5 September 2019 ABSTRACT Context. We carry out a solar survey with images of the photosphere, prominences, and corona at Pic du Midi observatory. This sur- vey, named CLIMSO (for CLIchés Multiples du SOleil), is in the following spectral lines: Fe XIII corona (1.075 µm), Hα (656.3 nm), and He I (1.083 µm) prominences, and Hα and Ca II (393.4 nm) photosphere. All frames cover 1.3 times the diameter of the Sun with an angular resolution approaching one arcsecond. The frame rate is one per minute per channel (weather permitting) for the prominences and chromosphere, and one per hour for the Fe XIII corona. This survey started in 2007 for the disk and prominences and in 2015 for the corona. We have almost completed one solar cycle and hope to cover several more, keeping the same wavelengths or adding others. Aims. We seek to make the CLIMSO images easier to use and more profitable for the scientific community. -

Project Periodic Report

PROJECT PERIODIC REPORT Grant Agreement number: 654208 Project acronym: EPN2020-RI Project title: EUROPLANET 2020 Research Infrastructure Call identifier: H2020-INFRAIA-1-2014-2015 Date of latest version of Annex I against which the assessment will be made: 1st March 2016 Periodic report: 1st □ 2nd X 3rd □ 4th □ Period covered: from 1 March 2017 to 31 August 2018 Project website address: http://www.europlanet-2020-ri.eu/ 1 Table of Content List of Figures 7 List of Tables 10 Table of Main Acronyms 11 Project Summary 11 1. Background 11 2. Europlanet 2020 Research Infrastructure - Impact to date 11 3. Collaborations with other EU projects 14 4. Future Plans and Sustainability 15 5. Conclusion 15 1. WP1: Management 16 1.1 Explanation of the work carried out by the beneficiaries and overview of progress 16 Task 1.1 - Management structure and tools 16 Task 1.2 - Regular operations of the management structure 16 Task 1.3 - Reporting 17 Task 1.4 - Call for proposals, evaluation and validation of Transnational Access visits 17 Task 1.5 – Sustainability and Financial Plan 26 Task 1.6 - Data management 27 1.2 Impact 27 2. Deviations from Annex 1 30 2.1 Amendments 30 2.2.2 Additional proposed changes 31 3. Financial reports 31 2. WP2 - TA 1: Planetary Field Analogues (PFA) 34 1.1 Explanation of the work carried out by the beneficiaries and overview of progress 34 Task 2.1-Rio Tinto (INTA) 34 Task 2.2-Ibn Battuta Centre (IRSPS) 35 Task 2.3- The glacial and volcanically active areas of Iceland, Iceland (MATIS) 36 Task 2.4 Lake Tirez (INTA) 37 Task 2.5-Danakil Depression, Ethiopia (IRSPS) 38 1.2 Impact 40 3. -

Istros 2013 Proceedings Download Link

Proceedings of the ISTROS 2013 International Conference Editors: M. Veselský and M. Venhart INSTITUTE OF PHYSICS, SLOVAK ACADEMY OF SCIENCES Bratislava 2015 ISBN 978-80-971975-0-6 Dear participants, we bring to you the proceedings of the conference ISTROS (Isospin, STructure, Reactions and energy Of Symmetry), which took place in the period between Sept 23 – - for meeting of Sept 27 2013 in Častá withPapiernička. experimental The declared and theoretical aim of theaspects conference of physics was of to exotic provide nuclei platform and states of nuclear international and Slovak scientists, active in the field of nuclear physics, specifically dealing matter, and we hope that this aim was fulfilled. presentationDuring the conference, is represented 36 invited in this and proceedings contributed in talks the formwere ofpresented, short artic coveringles, while the otheropen participantsproblems in decidedthe physics to abstain of exotic from nuclei this and thusof the their states presentations of nuclear matter.are represented Part of these only by their abstracts. In general, present time appears to modify traditional procedures and one of the victims are the conference proceedings in their habitual form. We are still convinced complementthat publication the of proceedi proceedingsngs iswith a part a briefof our summaryduties as organizersof history as of a servicenatural to sciences participants and and with this in mind we bring to you these proceedings. Besides the contributed articles, we technology in the territory of Slovakia, which bring some interesting facts about the progress of scientific and technical knowledge in Slovakia. - discussing interesting physics, and thus we aim to bring the second edition of the ISTROS As far as we can judge, you had a productive time at Častá Papiernička, spent meaningfully conference in the near future. -

1 Accepted for Publication in the Journal of the British

1 David Elijah Packer: cluster variables, meteors and the solar corona Jeremy Shears Abstract David Elijah Packer (1862-1936), a librarian by profession, was an enthusiastic amateur astronomer who observed from London and Birmingham. He first came to the attention of the astronomical community in 1890 when he discovered a variable star in the globular cluster M5, only the second periodic variable to be discovered in a globular cluster. He also observed meteors and nebulae, on one occasion reporting a brightening in the nucleus of the galaxy M77. However, his remarkable claims in 1896 that he had photographed the solar corona in daylight were soon shown to be flawed. Biographical sketch David Elijah Packer was born in Bermondsey, London, in 1862 April (1) the eldest child of Edward Packer (1820-1896) and Emma (Bidmead) Packer (1831-1918) (2). David attended the Free Grammar School of Saint Olave and Saint John at Southwark, where he performed well, especially in arithmetic, algebra and general mathematics (3). Edward Packer was a basket maker, as was his father and grandfather before him, the Packer family originally coming to London from Thanet, in Kent. The English basket-making industry was in decline during the second half of the nineteenth century due to the availability of cheaper imports from the continent. In spite of this, Edward was still in business in 1881, but the prospects for his son continuing in a trade that had made a living for generations of his ancestors were probably limited (4). Thus at the age of 18 we find David Elijah Packer working as an Oilman’s Assistant, supplying fuel for the oil lamps of London (5). -

Heritage Sites of Astronomy and Archaeoastronomy in the Context of the UNESCO World Heritage Convention

Heritage Sites of Astronomy and Archaeoastronomy in the context of the UNESCO World Heritage Convention Thematic Study, vol. 2 Clive Ruggles and Michel Cotte with contributions by Margaret Austin, Juan Belmonte, Nicolas Bourgeois, Amanda Chadburn, Danielle Fauque, Iván Ghezzi, Ian Glass, John Hearnshaw, Alison Loveridge, Cipriano Marín, Mikhail Marov, Harriet Nash, Malcolm Smith, Luís Tirapicos, Richard Wainscoat and Günther Wuchterl Edited by Clive Ruggles Published by Ocarina Books Ltd 27 Central Avenue, Bognor Regis, West Sussex, PO21 5HT, United Kingdom and International Council on Monuments and Sites Office: International Secretariat of ICOMOS, 49–51 rue de la Fédération, F–75015 Paris, France in conjunction with the International Astronomical Union IAU–UAI Secretariat, 98-bis Blvd Arago, F–75014 Paris, France Supported by Instituto de Investigaciones Arqueológicas (www.idarq.org), Peru MCC–Heritage, France Royal Astronomical Society, United Kingdom ISBN 978–0–9540867–6–3 (e-book) ISBN 978–2–918086–19–2 (e-book) © ICOMOS and the individual authors, 2017 All rights reserved A preliminary version of this publication was presented at a side-event during the 39th session of the UNESCO World Heritage Committee (39COM) in Bonn, Germany, in July 2015 Front cover photographs: Star-timing device at Al Fath, Oman. © Harriet Nash Pic du Midi Observatory, France. © Claude Etchelecou Chankillo, Peru. © Iván Ghezzi Starlight over the church of the Good Shepherd, Tekapo, New Zealand. © Fraser Gunn Table of contents Preface ......................................................................................................................................