1 Accepted for Publication in the Journal of the British

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LUNAR INTERACTIONS ABSTRACTS of PAPERS PRESENTED at the CONFERENCE on INTERACTIONS of the INTERPLANETARY PLASMA with the MODERN and ANCIENT MOON

LUNAR INTERACTIONS ABSTRACTS OF PAPERS PRESENTED AT THE CONFERENCE ON INTERACTIONS OF THE INTERPLANETARY PLASMA with the MODERN AND ANCIENT MOON ORGANIZED BY THE I. N 3 LUNAR SCIENCE INSTITUTE m I 3 AND THE I- 2 SPACE PHYSICS DEPARTMENT RICE UNIVERSITY sponsored by the NATIONAL AERONAUTICS m m AND 0 .. I-( OIW mrl SPACE ADMINISTRATION ZX CV OH IOI H WclU AND THE uux- V&H 0 NATIONAL SCIENCE FOUNDATION g,,,, wm. WWO@W u u ? ZZLOX€e HW5H vlOHU ffiMHrnfC 4 ffi H 2.~4~4a Edited by 3 dz ,.aV)ffiuJO ffiwcstn WPt.4" DAVID R. CRISWELL ,!a !a Pl r 4 W Pa4 %- rn ZW. and Or=4OcC+J fO Hi4 r WWF I rnU2.M ffiBZ* JOHN W. FREEMAN UUW4aJ I amor 0 alffiwffi E REPRODUCTION RESTRICTIONS OVERRIDDEN 2Z~OZ E 2 2 .: u Bmscientific ma Technical Information FaciLitX -eu $4 to) Copyright O 1974 by the Lunar Science Institute Conference held at George Williams College Lake Geneva Campus Williams Bay, Wisconsin 30 September - 4 October 1974 Compiled by and available from The Lunar Science Institute 3303 Nasa Road 1 Houston, Texas 77058 PREFACE The field of lunar science has essentially completed a period of exponential growth promoted by the national efforts of the 1960's to land on the moon. As normally happens in a diverse scientific community, the interpretations of specialized lunar data have reflected the precepts in the various specialized fields. Constant promotion of the broadest overviews between these diverse fields is appropriate to identify processes or phenomenon recog- nized in one avenue of investigation which may have great importance in explaining the data of other specialities. -

Eclipse Science Results: Past and Present

The Last Total Solar Eclipse of the Mil lennium in Turkey ASP Conference Series Vol W Livingston and A Ozgu c eds Eclipse Science Results Past and Present W Livingston National Solar Observatory NOAO PO Box Tucson AZ USA S Koutchmy Institut dAstrophysique de ParisCNRS Bis Boulevard Arago F Paris France Abstract We review the signicant advances that havebeenachieved by eclipse exp eriments First we note the anomaly that the corona was not even seen until relatively mo dern times Beginning in whitelight WL photographs suggested structures that must have b een dominated by magnetic elds This led to the disco very of surface magnetism in sunsp ots by Hale in the rst detection of cosmic magnetism Deli cate direct photographic observations conrmed the b ending of starlight near the eclipsed Sun as predicted by Einsteins General Theory of Rela tivity Chromospheric ash sp ectra indicated that the outer layer of the Sun was much hotter than the underlying photosphere leading to non lo cal thermo dynamic equilibrium concepts and the idea of various me chanical and wave pro cesses to maintain it Decades have been devoted to understanding the corona Discovery of its million degree plus tem p erature and guring howto heat it how co ol prominences can coexist within it all are topics to which eclipse observations havecontributed Totality without a Corona Eclipses have b een chronicled for o ver years but the corona escap ed b eing noticed until mo dern times The single exception Leonis Deaconis in AD mentions a certain dull and feeble glow -

Tazewell County Warren County Westmoreland~CO~Tt~~'~Dfla

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file, please contact us at NCJRS.gov. Tazewell County Warren County Westmoreland~CO~tt~~'~dfla Bedford Bristol Buena Vista Charl~esville ~ake clnr(~ F:Org I Heights Covington Danville Emporia Fairfax Falls ~.~tur.~~l~).~ ~urg Galax Hampton HarrisonburgHopj~ll~l Lexingtor~ynchburgl~'~assa ~ anassas Martinsville Newport News Norfolk Norton PetersbutrgPoque~o~ .Portsmouth Radford Richmond Roano~l~~ Salem ~th Bostor~t~nto SuffoLk Virginia Beach Waynesboro Williamsburg Winchester ~a~:~ingham Ceuul~ Carroll County Charlotte County Cra~ Col~ty Roar~ County~cco~Lac= Albemarle County Alleghany County Amelia County#~rlb~ ~NJ~/Ly,~ll~iatt~ County Arlington CountyAugula County Bath i~nty BerJ~rd Cd~t B.I.... ~1 County Botetourt County Brunswick County Buchanal~C~ut~ ~~wrtty Caroline County Charles City C~nty Ch~erfield~bunty C~rrke Co~t CT~-~eperCounty Dickenson County Dinwiddie County~ ~~~ r-'luvanneCounty Frederick County C~ucester (~unty C~yson (j~nty Gre~=~ County Greensville County Halifax County Hanover County ~ .(D~I~ I~liry Cottnty Highland County Isle of *~.P-.o.~t~l~me~y C~ ~county King George County King William County~r .(~,t~ ~ (~'~ Loudoun County Louisa County M~ Mat~s Cot]1~l~~ qt... ~ Montgomery County New Kent County North~ur~d County N~y County Page County Pittsylvania CouniY--Powhatan]~.~unty Princ~eorg, oC'6-~ty Prince William County Rappahannock County Richmol~l 0~)1~1=I~Woo~ Gi0ochtandCounty Lunenburg County Mecklenburl~nty Nelson Count Northampton CountyOrange County Patrick CountyPdn¢~ -

EPSC2015-913, 2015 European Planetary Science Congress 2015 Eeuropeapn Planetarsy Science Ccongress C Author(S) 2015

EPSC Abstracts Vol. 10, EPSC2015-913, 2015 European Planetary Science Congress 2015 EEuropeaPn PlanetarSy Science CCongress c Author(s) 2015 The “Station de Planétologie des Pyrénées” (S2P), a collaborative science program in the course of a long history at Pic du Midi observatory. F. Colas (1), A. Klotz (2), F. Vachier (1), M. Birlan (1), B. Sicardy (3), J. Lecacheux (3), M. Antuna (6), R. Behrend (4), C. Birnbaum (6), G. Blanchard (6), C. Buil (4,5), J. Caquel (6), M. Castets (5), C. Cavadore (4), B. Christophe (6), F. Cochard (4), J.L. Dauvergne (6), F. Deladerriere (6), M. Delcroix (6), V. Denoux (4), J.B. DeVanssay (6), P. Devechere (6), P. Dupouy (5), E. Frappa (6), S. Fauvaud (5), B. Gaillard (6), F. Jabet (6), M. Lavayssiere (6), T. Legault (6), A. Leroy (5), A. Maury (6), M. Meunier (6), C. Pellier (6), C. Rinner (4), E. Rolland (6), O. Stenuit (6), I. Testar (6), P. Thierry (4), O. Thizy (4), B. Tregon (5), F. Vaissiere (4), S. Vauclair (6), C. Viladrich (6), C. Angeli (6), J.E. Arlot (1), M. Assafin (28), D. Bancelin (1), D. Baratoux (29), N. Barrado-Izagirre (8), M.A. Barucci (3), L. Beauvalet (9), P. Bendjoya (13), J. Berthier (1), N. Biver (3), D. Bockelee-Morvan (3), D. Berard (3), S. Bouley (10), S. Bouquillon (9), P. Bourget (11), F. Bragas- Ribas (7), J. Camargo (7), B. Carry (1), S. Chevrel (2), M; Chevreton, (3), P. Colom (3), J. Crovisier (3), J. Demars (1), R. Despiau (2), P. Descamps (1), N. Dolez (2), A. -

February 2014 the Newsletter of the Barnard-Seyfert Astronomical Society

February TheECLIPSE 2014 The Newsletter of the Barnard-Seyfert Astronomical Society From the President Next Membership Meeting: February 19, 2014, 7:30 pm Cumberland Valley Professionals vs. amateurs… the distinctions have Girl Scout Council Building blurred over the years in different ways. There was 4522 Granny White Pike a time when mere money could get you the gear to have a professional observatory. Many large Program Topic: telescopes were built with private funds by Joshua Emery - interested individuals… think of William Hershel and the “Don Quixote” object (details on page 5) Percival Lowell. Then amateurs were pushed aside by large scale photography and the truly large telescopes that needed institutions to care for and run them… like the Mt. Wilson and Mt. Palomar observatories. Expensive ccd cameras, exotic cooling, the computing power needed even after In this Issue: glass plates were replaced put meaningful observations out of reach of amateurs. Then with President’s Message 1 the advent of the personal computer and digital Observing Highlights 2 cameras, the playing field was leveled by computers that anyone could own, low noise digital Happy Birthday, cameras and powerful software. Bernard Ferdinand Lyot by Robin Byrne 3Today, you can take the hobby or second life in astronomy as far as you wish, in partnership with Board Meeting Minutes January 8, 2014 6professionals. On any given clear night, enthusiasts around the world are recording not just pretty Membership Meeting Minutes pictures, but data. Our sheer numbers allow us to January 15, 2013 9look at things in depth and at a frequency not possible if we depended just on the large research Membership Information 10 telescopes. -

DMAAC – February 1973

LUNAR TOPOGRAPHIC ORTHOPHOTOMAP (LTO) AND LUNAR ORTHOPHOTMAP (LO) SERIES (Published by DMATC) Lunar Topographic Orthophotmaps and Lunar Orthophotomaps Scale: 1:250,000 Projection: Transverse Mercator Sheet Size: 25.5”x 26.5” The Lunar Topographic Orthophotmaps and Lunar Orthophotomaps Series are the first comprehensive and continuous mapping to be accomplished from Apollo Mission 15-17 mapping photographs. This series is also the first major effort to apply recent advances in orthophotography to lunar mapping. Presently developed maps of this series were designed to support initial lunar scientific investigations primarily employing results of Apollo Mission 15-17 data. Individual maps of this series cover 4 degrees of lunar latitude and 5 degrees of lunar longitude consisting of 1/16 of the area of a 1:1,000,000 scale Lunar Astronautical Chart (LAC) (Section 4.2.1). Their apha-numeric identification (example – LTO38B1) consists of the designator LTO for topographic orthophoto editions or LO for orthophoto editions followed by the LAC number in which they fall, followed by an A, B, C or D designator defining the pertinent LAC quadrant and a 1, 2, 3, or 4 designator defining the specific sub-quadrant actually covered. The following designation (250) identifies the sheets as being at 1:250,000 scale. The LTO editions display 100-meter contours, 50-meter supplemental contours and spot elevations in a red overprint to the base, which is lithographed in black and white. LO editions are identical except that all relief information is omitted and selenographic graticule is restricted to border ticks, presenting an umencumbered view of lunar features imaged by the photographic base. -

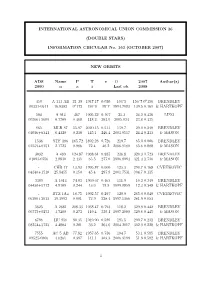

CIRCULAR No. 163 (OCTOBER 2007)

INTERNATIONAL ASTRONOMICAL UNION COMMISSION 26 (DOUBLE STARS) INFORMATION CIRCULAR No. 163 (OCTOBER 2007) NEW ORBITS ADS Name P T e (2000) 2007 Author(s) ®2000± n a i ! Last ob. 2008 450 A 111 AB 21y38 1947.17 0.020 104±5 156±7 000156 BRENDLEY 00321-0511 16.8382 000172 150±0 18±7 1994.7083 139.5 0.161 & HARTKOPF 504 A 914 467. 1905.32 0.107 35.3 24.2 0.436 LING 00366+5609 0.7709 0.468 118.2 291.9 2005.034 23.8 0.435 865 MLR 87 55.97 2020.45 0.513 139.7 29.0 0.240 BRENDLEY 01036+6341 6.4320 0.238 145.1 246.4 2003.9517 24.4 0.233 & MASON 1538 STF 186 165.72 1892.28 0.726 219.7 65.0 0.906 BRENDLEY 01559+0151 2.1723 0.986 72.4 40.2 2006.9180 65.6 0.888 & MASON 3032 A 469 124.87 1968.61 0.885 236.8 320.3 1.723 BRENDLEY 04093-0756 2.8830 2.435 65.5 277.0 1996.8984 321.4 1.736 & MASON - CHR 17 13.93 1995.87 0.600 125.3 290.7 0.168 CVETKOVIC 04340+1510 25.8455 0.150 45.4 297.9 2001.7531 304.7 0.135 3389 A 1014 74.83 1969.67 0.465 111.9 10.2 0.349 BRENDLEY 04430+5712 4.8109 0.244 13.0 78.8 1999.8859 12.3 0.348 & HARTKOPF - BTZ 1Aa 18.75 1992.57 0.297 120.9 265.0 0.040 CVETKOVIC 06290+2013 19.1992 0.081 72.9 228.4 1997.1366 281.9 0.053 5625 A 2681 208.33 1938.47 0.793 118.2 329.9 0.442 BRENDLEY 06575+0253 1.7280 0.273 119.4 339.1 1997.2000 329.6 0.445 & MASON 6796 HU 856 80.35 1949.90 0.589 185.5 299.7 0.231 BRENDLEY 08254+3723 4.4804 0.201 36.2 263.6 2004.2017 302.0 0.228 & HARTKOPF 7555 AC 5 AB 77.82 1957.65 0.736 194.7 53.1 0.585 BRENDLEY 09525-0806 4.6261 0.397 141.1 303.3 2006.3199 51.9 0.582 & HARTKOPF 1 NEW ORBITS (continuation) ADS Name P T e (2000) 2007 Author(s) ®2000± n a i ! Last ob. -

SPECIES REPORT Sierra Nevada Red Fox (Vulpes Vulpes Necator)

SPECIES REPORT Sierra Nevada Red Fox (Vulpes vulpes necator) U.S. FISH AND WILDLIFE SERVICE August 14, 2015 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................... 4 ACRONYMS AND SUBSTITUTIONS USED ............................................................................. 4 SPECIES AND SUBSPECIES DESCRIPTION ............................................................................ 5 TAXONOMY AND GENETICS ................................................................................................... 6 Taxonomic History and Relationship to Other Fox Subspecies ........................................... 6 Genetics ...................................................................................................................................... 7 RANGE AND DISTRIBUTION .................................................................................................... 8 Historical Range ........................................................................................................................ 8 Map 1: SNRF Historical Range in California .................................................................... 9 Current Distribution ............................................................................................................... 10 Map 2: SNRF Sighting Areas............................................................................................. 12 Table 1: SNRF Sighting Areas .......................................................................................... -

Observation of Venus and Mercury Transits from the Pic-Du-Midi Observatory

MEETING VENUS C. Sterken, P. P. Aspaas (Eds.) The Journal of Astronomical Data 19, 1, 2013 Observation of Venus and Mercury Transits from the Pic-du-Midi Observatory Guy Ratier 43 rue des Longues All´ees, F-45800 Saint-Jean-de-Braye, France Sylvain Rondi Soci´et´eAstronomique de France, 3 rue Beethoven, F-75016 Paris France Abstract. The Pic-du-Midi, on the French side of the Pyr´en´ees, became a state observatory in the summer of 1882. The first major astronomical event to be observed was the Venus transit of 6 December 1882. Unfortunately this attempt by the well-known Henry brothers was unsuccessful due to bad weather conditions. During the twentieth century, the Pic-du-Midi became famous for the quality of its solar and planetary observations. In the sixties, Jean R¨osch decided to use this experience to monitor the transits of Mercury. The objective was not to measure the parallax, but to determine the diameter of the planet in order to confirm its high density. Observations were made using a photometric method – the Hertzsprung method – during the transits of 1960, 1970 and 1973. The pioneer work of Ch. Boyer on the rotation of the Venus atmosphere as well as some experiments involving Lyot coronographs are also noteworthy. A Venus transit was finally observed on 8 June 2004 with a new CCD camera, providing a significant contribution to the model of the Venus mesosphere. This opened the field for new observations in 2012. 1. Early days of the Pic-du-Midi Observatory The site of the “Pic-du-Midi de Bigorre”, on the forefront of the Pyr´en´ees, has been known since ages as an ideal location to carry out astronomical observations. -

Appendix I Lunar and Martian Nomenclature

APPENDIX I LUNAR AND MARTIAN NOMENCLATURE LUNAR AND MARTIAN NOMENCLATURE A large number of names of craters and other features on the Moon and Mars, were accepted by the IAU General Assemblies X (Moscow, 1958), XI (Berkeley, 1961), XII (Hamburg, 1964), XIV (Brighton, 1970), and XV (Sydney, 1973). The names were suggested by the appropriate IAU Commissions (16 and 17). In particular the Lunar names accepted at the XIVth and XVth General Assemblies were recommended by the 'Working Group on Lunar Nomenclature' under the Chairmanship of Dr D. H. Menzel. The Martian names were suggested by the 'Working Group on Martian Nomenclature' under the Chairmanship of Dr G. de Vaucouleurs. At the XVth General Assembly a new 'Working Group on Planetary System Nomenclature' was formed (Chairman: Dr P. M. Millman) comprising various Task Groups, one for each particular subject. For further references see: [AU Trans. X, 259-263, 1960; XIB, 236-238, 1962; Xlffi, 203-204, 1966; xnffi, 99-105, 1968; XIVB, 63, 129, 139, 1971; Space Sci. Rev. 12, 136-186, 1971. Because at the recent General Assemblies some small changes, or corrections, were made, the complete list of Lunar and Martian Topographic Features is published here. Table 1 Lunar Craters Abbe 58S,174E Balboa 19N,83W Abbot 6N,55E Baldet 54S, 151W Abel 34S,85E Balmer 20S,70E Abul Wafa 2N,ll7E Banachiewicz 5N,80E Adams 32S,69E Banting 26N,16E Aitken 17S,173E Barbier 248, 158E AI-Biruni 18N,93E Barnard 30S,86E Alden 24S, lllE Barringer 29S,151W Aldrin I.4N,22.1E Bartels 24N,90W Alekhin 68S,131W Becquerei -

Of Treason, God and Testicles

Of Treason, God and Testicles Of Treason, God and Testicles Political Masculinities in British and American Films of the Early Cold War By Kathleen Starck Of Treason, God and Testicles: Political Masculinities in British and American Films of the Early Cold War By Kathleen Starck This book first published 2016 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2016 by Kathleen Starck All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-8918-0 ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-8918-6 For Gregor and Kalle—my two favourite men TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements .................................................................................... ix Chapter One ................................................................................................. 1 Introduction Chapter Two ................................................................................................ 5 Between Freedom and Totalitarianism: British and American Cinema and the Early Cold War British or American? .............................................................................. 5 Cold War Allies .................................................................................... -

Science Fiction Review 37

SCIENCE FICTION REVIEW $2.00 WINTER 1980 NUMBER 37 SCIENCE FICTION REVIEW (ISSN: 0036-8377) Formerly THE ALIEN CRITZ® P.O. BOX 11408 NOVEMBER 1980 — VOL.9, NO .4 PORTLAND, OR 97211 WHOLE NUMBER 37 PHONE: (503) 282-0381 RICHARD E. GEIS, editor & publisher PAULETTE MINARE', ASSOCIATE EDITOR PUBLISHED QUARTERLY FEB., MAY, AUG., NOV. SINGLE COPY — $2.00 COVER BY STEPHEN FABIAN SHORT FICTION REVIEWS "PET" ANALOG—PATRICIA MATHEWS.40 ASIMOV'S-ROBERT SABELLA.42 F8SF-RUSSELL ENGEBRETSON.43 ALIEN THOUGHTS DESTINIES-PATRICIA MATHEWS.44 GALAXY-JAFtS J.J, WILSON.44 REVIEWS- BY THE EDITOR.A OTT4I-MARGANA B. ROLAIN.45 PLAYBOY-H.H. EDWARD FORGIE.47 BATTLE BEYOND THE STARS. THE MAN WITH THE COSMIC ORIGINAL ANTHOLOGIES —DAVID A. , _ TTE HUNTER..... TRUESDALE...47 ESCAPE FROM ALCATRAZ. TRIGGERFINGER—an interview with JUST YOU AND Ft, KID. ROBERT ANTON WILSON SMALL PRESS NOTES THE ELECTRIC HORSEMAN. CONDUCTED BY NEAL WILGUS.. .6 BY THE EDITOR.49 THE CHILDREN. THE ORPHAN. ZOMBIE. AND THEN I SAW.... LETTERS.51 THE HILLS HAVE EYES. BY THE EDITOR.10 FROM BUZZ DIXON THE OCTOGON. TOM STAICAR THE BIG BRAWL. MARK J. MCGARRY INTERFACES. "WE'RE COMING THROUGH THE WINDOW" ORSON SCOTT CARD THE EDGE OF RUNNING WATER. ELTON T. ELLIOTT SF WRITER S WORKSHOP I. LETTER, INTRODUCTION AND STORY NEVILLE J. ANGOVE BY BARRY N. MALZBERG.12 AN HOUR WITH HARLAN ELLISON.... JOHN SHIRLEY AN HOUR WITH ISAAC ASIMOV. ROBERT BLOCH CITY.. GENE WOLFE TIC DEAD ZONE. THE VIVISECTOR CHARLES R. SAUNDERS BY DARRELL SCHWEITZER.15 FRANK FRAZETTA, BOOK FOUR.24 ALEXIS GILLILAND Tl-E LAST IMMORTAL.24 ROBERT A.W, LOWNDES DARK IS THE SUN.24 LARRY NIVEN TFC MAN IN THE DARKSUIT.24 INSIDE THE WHALE RONALD R.