Visualizza/Apri

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Youtube Comments As Media Heritage

YouTube comments as media heritage Acquisition, preservation and use cases for YouTube comments as media heritage records at The Netherlands Institute for Sound and Vision Archival studies (UvA) internship report by Jack O’Carroll YOUTUBE COMMENTS AS MEDIA HERITAGE Contents Introduction 4 Overview 4 Research question 4 Methods 4 Approach 5 Scope 5 Significance of this project 6 Chapter 1: Background 7 The Netherlands Institute for Sound and Vision 7 Web video collection at Sound and Vision 8 YouTube 9 YouTube comments 9 Comments as archival records 10 Chapter 2: Comments as audience reception 12 Audience reception theory 12 Literature review: Audience reception and social media 13 Conclusion 15 Chapter 3: Acquisition of comments via the YouTube API 16 YouTube’s Data API 16 Acquisition of comments via the YouTube API 17 YouTube API quotas 17 Calculating quota for full web video collection 18 Updating comments collection 19 Distributed archiving with YouTube API case study 19 Collecting 1.4 billion YouTube annotations 19 Conclusions 20 Chapter 4: YouTube comments within FRBR-style Sound and Vision information model 21 FRBR at Sound and Vision 21 YouTube comments 25 YouTube comments as derivative and aggregate works 25 Alternative approaches 26 Option 1: Collect comments and treat them as analogue for the time being 26 Option 2: CLARIAH Media Suite 27 Option 3: Host using an open third party 28 Chapter 5: Discussion 29 Conclusions summary 29 Discussion: Issue of use cases 29 Possible use cases 30 Audience reception use case 30 2 YOUTUBE -

Youtube 1 Youtube

YouTube 1 YouTube YouTube, LLC Type Subsidiary, limited liability company Founded February 2005 Founder Steve Chen Chad Hurley Jawed Karim Headquarters 901 Cherry Ave, San Bruno, California, United States Area served Worldwide Key people Salar Kamangar, CEO Chad Hurley, Advisor Owner Independent (2005–2006) Google Inc. (2006–present) Slogan Broadcast Yourself Website [youtube.com youtube.com] (see list of localized domain names) [1] Alexa rank 3 (February 2011) Type of site video hosting service Advertising Google AdSense Registration Optional (Only required for certain tasks such as viewing flagged videos, viewing flagged comments and uploading videos) [2] Available in 34 languages available through user interface Launched February 14, 2005 Current status Active YouTube is a video-sharing website on which users can upload, share, and view videos, created by three former PayPal employees in February 2005.[3] The company is based in San Bruno, California, and uses Adobe Flash Video and HTML5[4] technology to display a wide variety of user-generated video content, including movie clips, TV clips, and music videos, as well as amateur content such as video blogging and short original videos. Most of the content on YouTube has been uploaded by individuals, although media corporations including CBS, BBC, Vevo, Hulu and other organizations offer some of their material via the site, as part of the YouTube partnership program.[5] Unregistered users may watch videos, and registered users may upload an unlimited number of videos. Videos that are considered to contain potentially offensive content are available only to registered users 18 years old and older. In November 2006, YouTube, LLC was bought by Google Inc. -

Disturbed Youtube for Kids: Characterizing and Detecting Inappropriate Videos Targeting Young Children

Proceedings of the Fourteenth International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media (ICWSM 2020) Disturbed YouTube for Kids: Characterizing and Detecting Inappropriate Videos Targeting Young Children Kostantinos Papadamou, Antonis Papasavva, Savvas Zannettou,∗ Jeremy Blackburn,† Nicolas Kourtellis,‡ Ilias Leontiadis,‡ Gianluca Stringhini, Michael Sirivianos Cyprus University of Technology, ∗Max-Planck-Institut fur¨ Informatik, †Binghamton University, ‡Telefonica Research, Boston University {ck.papadamou, as.papasavva}@edu.cut.ac.cy, [email protected], [email protected] {nicolas.kourtellis, ilias.leontiadis}@telefonica.com, [email protected], [email protected] Abstract A large number of the most-subscribed YouTube channels tar- get children of very young age. Hundreds of toddler-oriented channels on YouTube feature inoffensive, well produced, and educational videos. Unfortunately, inappropriate content that targets this demographic is also common. YouTube’s algo- rithmic recommendation system regrettably suggests inap- propriate content because some of it mimics or is derived Figure 1: Examples of disturbing videos, i.e. inappropriate from otherwise appropriate content. Considering the risk for early childhood development, and an increasing trend in tod- videos that target toddlers. dler’s consumption of YouTube media, this is a worrisome problem. In this work, we build a classifier able to discern inappropriate content that targets toddlers on YouTube with Frozen, Mickey Mouse, etc., combined with disturbing con- 84.3% accuracy, and leverage it to perform a large-scale, tent containing, for example, mild violence and sexual con- quantitative characterization that reveals some of the risks of notations. These disturbing videos usually include an inno- YouTube media consumption by young children. Our analy- cent thumbnail aiming at tricking the toddlers and their cus- sis reveals that YouTube is still plagued by such disturbing todians. -

Youtube Yrityksen Markkinoinnin Välineenä

Lassi Tuomikoski Youtube yrityksen markkinoinnin välineenä Metropolia Ammattikorkeakoulu Tradenomi Liiketalouden koulutusohjelma Opinnäytetyö Lokakuu 2014 Tiivistelmä Tekijä Lassi Tuomikoski Otsikko Youtube yrityksen markkinoinnin välineenä Sivumäärä 47 sivua + 2 liitettä Aika 9.11.2014 Tutkinto Tradenomi Koulutusohjelma Liiketalous Suuntautumisvaihtoehto Markkinointi Ohjaaja lehtori Raisa Varsta Tämän opinnäytetyön tarkoituksena oli luoda ohjeistus oman sisällön luomiseen Youtubessa aloittelevalle yritykselle. Työn toisena tavoitteena on osoittaa, miten yritys pystyy hyödyntämään videonjakopalvelu Youtubea omassa liiketoiminnassaan muiden markkinoinnin keinojen avulla. Työn viitekehyksessä käydään läpi keskeisimmät käsitteet ja termit ja esitellään Youtube yrityksenä sekä videonjakopalveluna. Työssä kerrotaan, millä eri tavoin yritys voi näkyä Youtubessa ja Youtube yrityksen markkinoinnissa. Toiminnallisena osana työtä tuotettiin konkreettisten esimerkkien pohjalta ohjeistus Youtuben parissa aloittelevalle yritykselle siitä, kuinka päästä alkuun tehokkaassa ja yritykselle lisäarvoa tuottavassa sisällöntuottamisessa. Mitä asiota oman sisällön luomisessa täytyy ottaa huomioon ja millä keinoilla Youtubessa voidaan menestyä. Opinnäytetyön johtopäätöksenä todettiin, että ennen oman sisällön luomista on yrityksen sisältöstrategian oltava kunnossa. Sisällön tärkeyttä ei voi oman sisällön luomisessa tarpeeksi korostaa. Sisällön on oltava merkityksellistä asiakkaan kannalta. Avainsanat youtube, sisältömarkkinointi, sosiaalinen media Abstract -

"Youtube Kids" – Another Door Opener for Pedophilia?

Online link: www.kla.tv/12561 | Published: 08.06.2018 "YouTube Kids" – another door opener for Pedophilia? „Elsagate“: With the App „You Tube-Kids”, You Tube offers a service that is supposed to help parents to protect their children from inappropriate contents. However, while parents think they are safe, children are confronted with brutal videos including scenes of violence, perverse sex fantasies and cannibalism. These disturbing contents are staged by characters like Ice Queen "Elsa, “Spiderman” or “Mickey Mouse”. Is “YouTube-Kids” being abused as door-opener to make children receptive to abhorrent practices and pedophilia “socially acceptable”? Since 2015 YouTube has been offering a service with the App "YouTube Kids" to help parents and children to receive only those video-clips in the proposal bar that are child and family friendly. An algorithm (that is a method of calculation) takes over the function of filtering the content that is unsuitable for children. The App has been installed more than 60 million times and is available in 37 countries and eight languages – since September 2017 also in Germany. Unfortunately, this App – that promises safety for children – however, is in no way as reliable as many parents wish it was. On the contrary: it is even dangerous. Already since June 2016 media reports have increased that children are confronted with a number of brutal children's series and animated videos that – beyond any morality – convey extremely repulsive content and that are filled with topics that are in no way suitable for children. It's about violence scenes, perverse sex fantasies or cannibalism. -

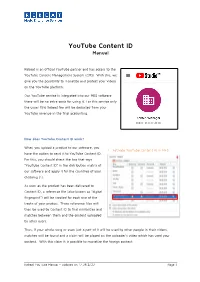

Manual Youtube Content ID

YouTube Content ID Manual Rebeat is an official YouTube partner and has access to the YouTube Content Management System (CMS). With this, we give you the possibility to monetize and protect your videos on the YouTube platform. Our YouTube service is integrated into our MES software – there will be no extra costs for using it. For this service only the usual 15% Rebeat fee will be deducted from your YouTube revenue in the final accounting. How does YouTube Content ID work? When you upload a product to our software, you 1. Activate YouTube Content ID in MES have the option to send it to YouTube Content ID. For this, you should check the box that says “YouTube Content ID” in the distribution matrix of our software and apply it for the countries of your choosing (1). As soon as the product has been delivered to Content ID, a reference file (also known as “digital fingerprint”) will be created for each one of the tracks of your product. These reference files will then be used by Content ID to find similarities and matches between them and the content uploaded by other users. Thus, if your whole song or even just a part of it will be used by other people in their videos, matches will be found and a claim will be placed on the uploader’s video which has used your content. With this claim it is possible to monetize the foreign content. Rebeat YouTube Manual – updated on 17.08.2020 Page 1 With the help of Content ID we can also claim any of your content manually. -

You(Tube), Me, and Content ID: Paving the Way for Compulsory Synchronization Licensing on User-Generated Content Platforms Nicholas Thomas Delisa

Brooklyn Law Review Volume 81 | Issue 3 Article 8 2016 You(Tube), Me, and Content ID: Paving the Way for Compulsory Synchronization Licensing on User-Generated Content Platforms Nicholas Thomas DeLisa Follow this and additional works at: https://brooklynworks.brooklaw.edu/blr Part of the Intellectual Property Law Commons, and the Internet Law Commons Recommended Citation Nicholas T. DeLisa, You(Tube), Me, and Content ID: Paving the Way for Compulsory Synchronization Licensing on User-Generated Content Platforms, 81 Brook. L. Rev. (2016). Available at: https://brooklynworks.brooklaw.edu/blr/vol81/iss3/8 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at BrooklynWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Brooklyn Law Review by an authorized editor of BrooklynWorks. You(Tube), Me, and Content ID PAVING THE WAY FOR COMPULSORY SYNCHRONIZATION LICENSING ON USER- GENERATED CONTENT PLATFORMS INTRODUCTION Ever wonder about how the law regulates your cousin’s wedding video posted on her YouTube account? Most consumers do not ponder questions such as “Who owns the content in my video?” or “What is a fair use?” or “Did I obtain the proper permission to use Bruno Mars’s latest single as the backing track to my video?” These are important questions of law that are answered each day on YouTube1 by a system called Content ID.2 Content ID identifies uses of audio and visual works uploaded to YouTube3 and allows rights holders to collect advertising revenue on that content through the YouTube Partner Program.4 It is easy to see why Content ID was implemented—300 hours of video are uploaded to YouTube per minute.5 Over six billion hours of video are watched each month on YouTube (almost an hour for every person on earth),6 and it is unquestionably the most popular streaming video site on the Internet.7 Because of the staggering amount of content 1 See A Guide to YouTube Removals,ELECTRONIC fRONTIER fOUND., https://www.eff.org/issues/intellectual-property/guide-to-youtube-removals [http://perma.cc/ BF4Y-PW6E] (last visited June 6, 2016). -

Dave Lougee, President and CEO, TEGNA, Inc

Participant Biographies Ty Ahmad-Taylor, Vice President, Business Product Marketing, Facebook, Inc. As Vice President of Business Product Marketing, Ty leads Facebook’s monetization strategy and global go-to- market efforts for products that connect people and businesses on the platform. Prior to Facebook, Ty served as CEO of THX Ltd., a global media and entertainment company. Ty brings to Facebook 25+ years of information design, 20+ years of consumer-facing software and product development leadership, along with interactive television services development experience. Ty has a diverse portfolio of technology and hardware patents, and has held roles at several startups and large media and consumer electronic companies, including Viacom, Comcast, The New York Times, and Samsung. Kevin Arrix, Senior Vice President, DISH Media Kevin Arrix, Senior Vice President of DISH Media Sales, is responsible for DISH TV’s and Sling TV’s advertising sales, analytics and operations. He leads the team spearheading the company’s advanced advertising initiatives, which include cross-platform addressable, programmatic sales and dynamic ad insertion. Arrix is a seasoned revenue executive with 20+ years of experience leading Sales, Operations, Client Services and Strategy teams. He is a recognized thought-leader fluent in the various disciplines of digital and mobile advertising and marketing. Prior to joining DISH in 2018, Arrix served as Chief Revenue Officer of Verve, leading the mobile marketing platform’s Direct and Enterprise sales, customer success and advertising operations teams. Prior to Verve, Arrix served as Chief Revenue Officer at mobile rewards entertainment platform Viggle, where he arrived prior to product launch to build out the sales team, the operational infrastructure and revenue foundation. -

70Th Annual Tech & Engineering Brand Opportunities

PROPRIETARY & CONFIDENTIAL BRAND OPPORTUNITIES APRIL 7, 2019 PROPRIETARY & CONFIDENTIAL 2 Program Book Advertising Rates Trimmed Size (in inches) 2019 Net Rate Format Width Height 4-Color CMYK Black & White Rear Cover 8⅛ 10⅞ $11,000 — 2-Page Spread 16¼ 10⅞ $9,500 — Center Spread Add $750 Inside Cover(s) Add $500 Full Page 8⅛ 10⅞ $6,500 $5,500 Inside Cover(s) Add $500 ⅔ Page 4½ 10 $4,750 $3,850 ½ Page Horizontal 7 4⅞ $4,000 $3,000 ⅓ Page Horizontal 4½ 4⅞ $3,000 $2,250 ⅓ Page Vertical 2¼ 8⅞ $3,000 $2,250 ¼ Page Corner 3⅜ 4⅞ $2,500 $1,750 ¼ Page Horizontal Strip 7 2½ $2,500 $1,750 Specific Editorial Adjacency (All Formats) Add 10% Custom formats and packages, including wraps and inserts, are available upon request. PROPRIETARY & CONFIDENTIAL 3 Ticket and Sponsorship Options Individual Gold Pedestal Atom Wings Presenting $750 $6,500 $7,500 $10,000 $20,000 $50,000 Single Ticket Standard Premium Premium 2x Premium 3x Premium Tickets General Seating Table of 10 Table of 12 Table of 12 Tables of 12 Tables of 12 Featured Logo in Name in Logo in Sponsor Listings + Logo Above Sponsor Recognition — — Sponsor Listings Sponsor LIstings Sole Sponsorship Show Title in of Reception Bar All Displays Logo in Featured Logo in Logo on Front Name in Sponsor Listings Cover + Ad on Print Program — — Sponsor Listings Sponsor Listings + Rear Cover, Wrap, + ½ Page Ad Full Page Ad or Center Spread Featured on Show Page Featured on Event Page Name in Logo in 2 Image/Link Posts + Digital / Social — — Sponsor Listings + 2 Image/Link Posts + Hosted Videos on Each Sponsor Listings Hosted Videos on Each Social Network Image/Link Post Social Network Branding on all Show Clips Step & Repeat — — — — Featured Logo Featured Logo “Emmy Showcase” Featured Pedestal Gallery of featured honorees, with — — — Featured Pedestal + Exclusive prime placement in NAB show lobby. -

WILL Youtube SAIL INTO the DMCA's SAFE HARBOR OR SINK for INTERNET PIRACY?

THE JOHN MARSHALL REVIEW OF INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY LAW WILL YoUTUBE SAIL INTO THE DMCA's SAFE HARBOR OR SINK FOR INTERNET PIRACY? MICHAEL DRISCOLL ABSTRACT Is YouTube, the popular video sharing website, a new revolution in information sharing or a profitable clearing-house for unauthorized distribution of copyrighted material? YouTube's critics claim that it falls within the latter category, in line with Napster and Grokster. This comment, however, determines that YouTube is fundamentally different from past infringers in that it complies with statutory provisions concerning the removal of copyrighted materials. Furthermore, YouTube's central server architecture distinguishes it from peer-to-peer file sharing websites. This comment concludes that any comparison to Napster or Grokster is superficial, and overlooks the potential benefits of YouTube to copyright owners and to society at large. Copyright © 2007 The John Marshall Law School Cite as Michael Driscoll, Will YouTube Sail into the DMCA's Safe Harboror Sink for Internet Piracy?, 6 J. MARSHALL REV. INTELL. PROP. L. 550 (2007). WILL YoUTUBE SAIL INTO THE DMCA's SAFE HARBOR OR SINK FOR INTERNET PIRACY? MICHAEL DRISCOLL* 'A sorry agreement is better than a good suit in law." English Proverb1 INTRODUCTION The year 2006 proved a banner year for YouTube, Inc. ("YouTube"), a well- known Internet video sharing service, so much so that Time Magazine credited YouTube for making "You" the Person of the Year. 2 Despite this seemingly positive development for such a young company, the possibility of massive copyright 3 infringement litigation looms over YouTube's future. For months, YouTube was walking a virtual tightrope by obtaining licensing agreements with major copyright owners, yet increasingly gaining popularity through its endless video selection, both legal and otherwise. -

SCMS 2019 Conference Program

CELEBRATING SIXTY YEARS SCMS 1959-2019 SCMSCONFERENCE 2019PROGRAM Sheraton Grand Seattle MARCH 13–17 Letter from the President Dear 2019 Conference Attendees, This year marks the 60th anniversary of the Society for Cinema and Media Studies. Formed in 1959, the first national meeting of what was then called the Society of Cinematologists was held at the New York University Faculty Club in April 1960. The two-day national meeting consisted of a business meeting where they discussed their hope to have a journal; a panel on sources, with a discussion of “off-beat films” and the problem of renters returning mutilated copies of Battleship Potemkin; and a luncheon, including Erwin Panofsky, Parker Tyler, Dwight MacDonald and Siegfried Kracauer among the 29 people present. What a start! The Society has grown tremendously since that first meeting. We changed our name to the Society for Cinema Studies in 1969, and then added Media to become SCMS in 2002. From 29 people at the first meeting, we now have approximately 3000 members in 38 nations. The conference has 423 panels, roundtables and workshops and 23 seminars across five-days. In 1960, total expenses for the society were listed as $71.32. Now, they are over $800,000 annually. And our journal, first established in 1961, then renamed Cinema Journal in 1966, was renamed again in October 2018 to become JCMS: The Journal of Cinema and Media Studies. This conference shows the range and breadth of what is now considered “cinematology,” with panels and awards on diverse topics that encompass game studies, podcasts, animation, reality TV, sports media, contemporary film, and early cinema; and approaches that include affect studies, eco-criticism, archival research, critical race studies, and queer theory, among others. -

Elsagate” Phenomenon: Disturbing Children’S Youtube Content and New Frontiers in Children’S Culture

Selected Papers of #AoIR2019: The 20th Annual Conference of the Association of Internet Researchers Brisbane, Australia / 2-5 October 2019 EXAMINING THE “ELSAGATE” PHENOMENON: DISTURBING CHILDREN’S YOUTUBE CONTENT AND NEW FRONTIERS IN CHILDREN’S CULTURE Jessica Balanzategui Swinburne University of Technology Contemporary children are turning to online video streaming as an “alternative for TV” (Ha 2018, 1) in increasing numbers (see Australian Communications and Media Authority 2017, 20-22). In addition, US-based global video streaming platforms, primarily YouTube and Netflix, are becoming “more influential in screen production ecologies” when it comes to children’s content (Potter 2017a, 22). Yet, as increasing numbers of children consume much of their video content outside of the legacy media spaces of film and television, serious concerns are being raised in policy, advocacy (Centre for Digital Democracy, 2018), and journalistic (Bridle, 2017) discussions around the globe because many new children’s video streaming genres are not “child-appropriate” according to extant definitions and guidelines, such as the internationally endorsed Children’s Television Charter. Alarms have been raised in relation to new genres on YouTube in particular. For instance, in an influential journalistic exposé, James Bridle (2017) argues that YouTube content seemingly aimed at child-viewers is tantamount to “a kind of infrastructural violence” against children’s wellbeing, a point echoed in many other recent long-form journalistic investigations (see for instance Orphanides 2018). Public concerns about the strange approach to children’s content exhibited by various YouTube genres have become so prevalent that the neologism “Elsagate” is now commonly used in media reportage to describe the scandal.