La Ck & W Hite K Nig Ht

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Read an Extract

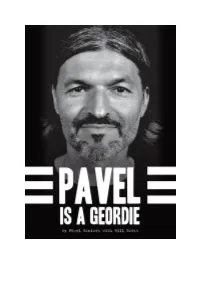

PAVEL IS A GEORDIE Pavel Srnicek Will Scott Contents 1 Pavel’s return 2 Kenny Conflict 3 Budgie crap, crap salad and crap in the bath 4 Dodgy keeper and Kevin who? 5 Got the t-shirt 6 Hooper challenge 7 Cole’s goals gone 8 Second best 9 From Tyne to Wear? 10 Pavel is a bairn 11 Stop or I’ll shoot! 12 Magpie to Owl 13 Italian job 14 Pompey, Portugal and blowing bubbles 15 Country calls 16 Testimonial 17 Slippery slope 18 Best Newcastle team 19 Best international team 20 The Naked Chef 21 Epilogue FOREWORD Spending the first ten years of my football career away from St James’ Park didn’t mean I wasn’t aware of what was going on at my home town club. As a Geordie and a Newcastle United supporter, I always kept a keen interest on what was happening on Tyneside in the early stages of my career at Southampton and Blackburn. Although it was common for clubs to sign foreign players in the early 1990s, the market wasn’t saturated the way it is now, but it was certainly unusual for teams to invest in foreign goalkeepers. And Pavel’s arrival on Tyneside certainly caused a stir. He turned up on the club’s doorstep when it was struggling at the wrong end of the old Second Division. It must have been a baptism of fire for the young Czech goalkeeper. Not only did he have to adapt to a new style of football he had to settle in to a new town and culture. -

European Qualifiers

EUROPEAN QUALIFIERS - 2014/16 SEASON MATCH PRESS KITS Cardiff City Stadium - Cardiff Monday 13 October 2014 20.45CET (19.45 local time) Wales Group B - Matchday -10 Cyprus Last updated 08/07/2016 01:51CET EUROPEAN QUALIFIERS OFFICIAL SPONSORS Team facts 2 Legend 4 1 Wales - Cyprus Monday 13 October 2014 - 20.45CET (19.45 local time) Match press kit Cardiff City Stadium, Cardiff Team facts UEFA European Championship records: Wales History 2012 – did not qualify 2008 – did not qualify 2004 – did not qualify 2000 – did not qualify 1996 – did not qualify 1992 – did not qualify 1988 – did not qualify 1984 – did not qualify 1980 – did not qualify 1976 – did not qualify 1972 – did not qualify 1968 – did not qualify 1964 – did not qualify 1960 – did not participate Qualifying win 7-0: Wales v Malta, 25/10/78 Qualifying loss 5-0: Georgia v Wales, 16/11/94 Overall appearances 29: Gary Speed 25: Neville Southall 24: Craig Bellamy 24: Ryan Giggs 23: Ian Rush Overall goals 7: Ian Rush 7: Gareth Bale 5: Craig Bellamy 5: Simon Davies 5: Dean Saunders 5: John Toshack UEFA European Championship records: Cyprus History 2012 – did not qualify 2008 – did not qualify 2004 – did not qualify 2000 – did not qualify 1996 – did not qualify 1992 – did not qualify 1988 – did not qualify 1984 – did not qualify 1980 – did not qualify 1976 – did not qualify 1972 – did not qualify 1968 – did not qualify 1964 – did not participate 1960 – did not participate Qualifying win 4-0: Cyprus v San Marino, 10/02/99 Qualifying loss 8-0: Spain v Cyprus, 08/09/99 2 Wales - Cyprus -

Steven Gerrard Autobiografia

STEVEN GERRARD AUTOBIOGRAFIA Tłumaczenie LFC.pl Drodzy Paostwo! Jeśli macie przed sobą tą książkę z nadzieją, by dowiedzied się tylko o karierze Stevena Gerrarda to prawdopodobnie się zawiedziecie. Jeżeli jednak pragniecie przeczytad o życiu i sukcesach Naszego kapitana to nie mogliście lepiej trafid. Steven Gerrard to bohater dla wielu milionów, nie tylko kapitan Liverpool Football Club, ale także ważny element reprezentacji Anglii. ‘Gerro’ po raz pierwszy opowiedział historię swojego życia, które od najmłodszych lat było przepełnione futbolem. Ze pełną szczerością wprowadził czytelnika w swoje prywatne życie przywołując dramatyczne chwile swojego dzieciostwa, a także początki w Liverpoolu i sukcesy jak niewiarygodny finał w Stambule w maju 2005 roku. Steven ukazuje wszystkim, jak ważne miejsce w jego sercu zajmuje rodzina a także zdradza wiele sekretów z szatni. Oddajemy do Paostwa dyspozycji całośd biografii Gerrarda z nadzieją, iż się nie zawiedziecie i ochoczo przystąpicie do lektury, która niejednokrotnie może doprowadzid do wzruszenia. Jeśli Steven nie jest jeszcze Waszym bohaterem, po przeczytaniu tego z pewnością będzie ... Adrian Kijewski redaktor naczelny LFC.pl Oryginał: Autor: Steven Gerrard Rok wydania: 2006 Wydawca: Bantam Press W tłumaczeniu książki uczestniczyli: Katarzyna Buczyoska (12 rozdziałów) Damian Szymandera (8 rozdziałów) Angelika Czupryoska (1 rozdział) Grzegorz Klimek (1 rozdział) Krzysztof Pisarski (1 rozdział) Redakcja serwisu LFC.pl odpowiedzialna jest tylko i wyłącznie za tłumaczenie oryginału na język Polski, nie przypisujemy sobie tym samym praw do tekstu wydanego przez Bentam Press. Polska wersja, przetłumaczona przez LFC.pl, nie może byd sprzedawana. Steven Gerrard – Autobiografia (tłumaczenie LFC.pl) Strona 2 Wstęp iedy tylko przyjeżdżam na Anfield zwalniam przy Shankly Gates. Jednocześnie kieruje wzrok na Hillsborough Memorial. -

Download the App Now

The magazine of the League Managers Association Issue 10: Winter 2011 £7.50 “Having a strong spirit is essential” M ART IN O ’ N EI LL Ossie Ardiles WHAT DO Aidy Boothroyd LEADERS DO? The big question... Herbert Chapman asked and answered Terry Connor Roy Keane SECOND IN Matt Lorenzo COMMAND Mark McGhee The assistant Gary Speed manager’s role revealed BOXING CLEVER Team The changing face of the TV rights market Issue 10 spirited : Winter 2011 Martin O’Neill on learning from Clough, the art of team building and the challenges ahead SPONSORED BY We’ve created an oil SO STRONG WE HAD TO ENGINEER THE TESTS TO PROVE IT. ENGINEERED WITH Today’s engines work harder, run hotter and operate under higher pressures, to demand maximum performance in these conditions you need a strong oil. That’s why we engineered Castrol EDGE, with new Fluid Strength Technology™. Proven in testing to minimise metal to metal contact, maximising engine performance and always ready to adapt wherever your drive takes you. Find out more at castroledge.com Recent economic and political events in Europe’s autumn THE have highlighted the dangers of reckless over-spending, poor debt management and short-sighted, short-term MANAGERS’ leadership. The macro-economic solutions being worked on in Europe’s major capitals have micro-economic lessons VOICE in them. Short-term fixes do not bring about long-term solutions, stability and prosperity. “We hope 2012 The LMA’s Annual Management Conference held in October at the magnificent Emirates stadium, brought will not see a repeat football and business together for a day of discussion and debate on the subject of leadership. -

Handbook Season 2021/22 Professional Development League Contents

Handbook Season 2021/22 Professional Development League Contents Club Information ....................................................................................................................02 Format .........................................................................................................................................11 Fixtures ........................................................................................................................................12 Rules of the Professional Development League ..................................................24 Professional Development League Club Information Club Information Barnsley Cardiff City Correspondence Address: Oakwell Stadium, Academy Manager: Bobby Hassell Correspondence Address: Cardiff City Academy Manager: James McCarthy Grove Street, Barnsley, S71 1ET Email: [email protected] Stadium, Leckwith Road, Cardiff, CF11 8AZ Email: [email protected] Tel: 01226 211211 Lead Coach: Martin Devaney Tel: 02920 643784 Lead Coach Steve Morison Email: [email protected] Tel: 01226 211211 Email: [email protected] Tel: 07525 709002 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Home Venue Address: Oakwell Training Administration: Jenny Pead Home Venue Address: Leckwith Stadium, Administration: Scott Dommett Ground, Grove Street, Barnsley, S71 1ET Position: Academy Secretary Leckwith Road, Cardiff, CF11 8AZ Position: Football Administrator Tel: 01226 211211 Tel: 02920 643784 Mobile: 07412 465922 -

Walking and Cycling Connectivity Study West Blackburn

WALKING & CYCLING CONNECTIVITY STUDY WEST BLACKBURN June 2020 CONTENT: 1.0 Overview 2.0 Baseline Study 3.0 Detailed Trip Study 4.0 Route Appraisal and Ratings 5.0 Suggested Improvements & Conclusions 1.0 OVERVIEW West Blackburn 1.0 Introduction Capita has been appointed by Blackburn with Darwen expected to deliver up to 110 dwellings); pedestrian and cycle movement within the area. Borough Council (BwDBC) to prepare a connectivity • Pleasington Lakes (approximately 46.2 Ha of study to appraise the potential impact of development developable land, expected to deliver up to 450 Study Area sites on the local pedestrian network. dwellings;) • Eclipse Mill site in Feniscowles, expected to deliver The study area is outlined on the plan opposite. In This study will consider the implications arising 52 dwellings; general, the area comprises the land encompassed from the build-out of new proposed housing sites • Tower Road site in Cherry Tree, expected to deliver by the West Blackburn Growth Zone. The study area for pedestrian travel, in order to identify potential approximately 30 dwellings. principally consists of the area bounded by Livesey gaps in the existing highway and sustainable travel Branch Road to the north, A666 Bolton Road to the provision. It will also consider potential options for east, the M65 to the south, and Preston Old Road and The study also takes into account the committed any improvements which may be necessary in order to the Blackburn with Darwen Borough Boundary to the improvements that were delivered as part of the adequately support the developments. west Pennine Reach scheme. This project was completed in April 2017 to create new bus rapid transit corridors Findings will also be used to inform the Local Plan which will reduce bus journey times and improve the Review currently underway that will identify growth reliability of services. -

Sample Download

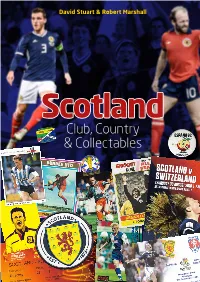

David Stuart & RobertScotland: Club, Marshall Country & Collectables Club, Country & Collectables 1 Scotland Club, Country & Collectables David Stuart & Robert Marshall Pitch Publishing Ltd A2 Yeoman Gate Yeoman Way Durrington BN13 3QZ Email: [email protected] Web: www.pitchpublishing.co.uk First published by Pitch Publishing 2019 Text © 2019 Robert Marshall and David Stuart Robert Marshall and David Stuart have asserted their rights in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 to be identified as the authors of this work. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher and the copyright owners, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the terms stated here should be sent to the publishers at the UK address printed on this page. The publisher makes no representation, express or implied, with regard to the accuracy of the information contained in this book and cannot accept any legal responsibility for any errors or omissions that may be made. A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. 13-digit ISBN: 9781785315419 Design and typesetting by Olner Pro Sport Media. Printed in India by Replika Press Scotland: Club, Country & Collectables INTRODUCTION Just when you thought it was safe again to and Don Hutchison, the match go back inside a quality bookshop, along badges (stinking or otherwise), comes another offbeat soccer hardback (or the Caribbean postage stamps football annual for grown-ups) from David ‘deifying’ Scotland World Cup Stuart and Robert Marshall, Scottish football squads and the replica strips which writing’s answer to Ernest Hemingway and just defy belief! There’s no limit Mary Shelley. -

Lee Bowyer Talks Leeds United, with Jon Howe

Y PHONE RINGS at 10.42am. It’s Lee Bowyer. Of course. He immediately apologises for not answering when I rang at the pre-arranged time of 9.30am; when he dropped his two six- year-old kids off at school he realised he had to attend a Harvest Festival assembly. I gave a knowing laugh, having been caught short in the same situation on the school run a few times. And here I was, swapping stories with Lee Bowyer on the humdrum trials of being a parent to young kids. Two normal blokes with normal concerns. We were aligned in the everyday travails of life’s rich tapestry, and yet fifteen years ago Lee Bowyer was my favourite Leeds United player. In fact, he was my ‘last’ favourite Leeds United player. After Lee Bowyer left Leeds United in 2003, the Catchinghi emotional strain of putting all my faith in one player seemed futile. Plus, well, you’ve watched Leeds United over the last decade, haven’t you? The enduring and relentless echo of ‘L’Bowya, L’Bowya’ around Elland Road has left more of up with the a lasting impression than the same chant for the perhaps more exalted Tony Yeboah. Purely because it was in our songbook for longer. Not simply out of habit, but as a result of performance; for years, every game, without fail. He was that good. In 2015, can you imagine Running such a thing? Lee Bowyer has endured a lifetime of not being able to fully explain himself. I initially approached him to write his autobiography. -

'Black and Whiters': the Relative Powerlessness of 'Active' Supporter

‘Black and whiters’: The relative powerlessness of ‘active’ supporter organization mobility at English Premier League football clubs This article examines the reaction by Newcastle United supporters to the resignation of Kevin Keegan as Newcastle United manager in September 2008. Unhappy at the ownership and management structure of the club following Keegan’s departure, a series of supporter-led meetings took place that led to the creation of Newcastle United Supporters’ Club and Newcastle United Supporters’ Trust. This article draws on a non-participant observation of these meetings and argues that although there are an increasing number of ‘active’ supporters throughout English football, ultimately it is the significant number of ‘passive’ supporters who hamper the inclusion of supporters’ organizations at higher-level clubs. The article concludes by suggesting that clubs, irrespective of wealth and success, need to recognize the long-term value of supporters. Failure to do so can result in fan alienation and ultimately decline (as seen with the recent cases of Coventry City and Portsmouth). Keywords: fans; Premier League; supporter clubs; inclusion; mobilization Introduction Over the last twenty years there have been many changes to English football. In this post- Hillsborough era, the most significant change has been the introduction of a Premier League in 1992 and its growing relationship with satellite television (most notably BSkyB). This global exposure has helped increase the number of sponsors and overseas investors and has -

A Football Journal by Football Radar Analysts

FFoooottbbaallll RRAADDAARR RROOLLIIGGAANN JJOOUURRNNAALL IISSSSUUEE FFOOUURR a football journal BY football radar analysts X Contents GENERATION 2019: YOUNG PLAYERS 07 Football Radar Analysts profile rising stars from around the globe they tip to make it big in 2019. the visionary of nice 64 New ownership at OGC Nice has resulted in the loss of visionary President Jean-Pierre Rivere. Huddersfield: a new direction 68 Huddersfield Town made the bold decision to close their academy, could it be a good idea? koncept, Kompetenz & kapital 34 Stepping in as Leipzig coach once more, Ralf Rangnick's modern approach again gets results. stabaek's golden generation 20 Struggling Stabaek's heavy focus on youth reaps rewards in Norway's Eliteserien. bruno and gedson 60 FR's Portuguese analysts look at two players named Fernandes making waves in Liga Nos. j.league team of the season 24 The 2018 season proved as unpredictable as ever but which players stood out? Skov: THE DANISH SNIPER 38 A meticulous appraisal of Danish winger Robert Skov's dismantling of the Superligaen. europe's finishing school 43 Belgium's Pro League has a reputation for producing world class talent, who's next? AARON WAN-BISSAKA 50 The Crystal Palace full back is a talented young footballer with an old fashioned attitude. 21 under 21 in ligue 1 74 21 young players to keep an eye on in a league ideally set up for developing youth. milan's next great striker? 54 Milan have a history of legendary forwards, can Patrick Cutrone become one of them? NICOLO BARELLA: ONE TO WATCH 56 Cagliari's midfielder has become crucial for both club and country. -

Futera Fans Selection Newcastle 1999

soccercardindex.com Futera Fans Selection Newcastle 1999 CUTTING EDGE HEROES INSERT CARDS 1 Temuri Ketsbaia 55 Malcolm Macdonald 2 David Batty 56 George Robledo CUTTING EDGE EMBOSSED 3 John Barnes 57 Ivor Allchurch CE1 Temuri Ketsbaia 4 Alesssandro Pistone 58 Chris Waddle CE2 David Batty 5 Alan Shearer 59 Paul Gascoigne CE3 John Barnes 6 Shay Given 60 Kevin Keegan CE4 Alesssandro Pistone 7 Gary Speed 61 Led Ferdinand CE5 Alan Shearer 8 Robert Lee 62 Peter Beardsley CE6 Shay Given 9 Stuart Pearce 63 Jackie Milburn CE7 Gary Speed STARS CE8 Robert Lee THE SQUAD 64 David Batty CE9 Stuart Pearce 10 Philippe Albert 65 Stuart Pearce 11 Lionel Perez 66 Laurence Charvet HOT SHOTS CHROME EMBOSSED 12 Keith Gillespie HS1 Temuri Ketsbaia 13 Des Hamilton LIGHTNING STRIKES HS2 Steve Watson 14 Dietmar Hamann 67 Alan Shearer HS3 John Barnes 15 Laurence Charvet 68 Alessandro Pistone HS4 Nikolaos Dabizas 16 Warren Barton 69 Steve Watson HS5 Alan Shearer 17 Steve Howey HS6 Gary Speed 18 Aaron Hughes WANTED HS7 Robert Lee 19 David Batty 70 Stephane Guivarc’h HS8 Keith Gillespie 20 Robert Lee 71 Laurence Charvet HS9 Andreas Andersson 21 John Barnes 72 Dietmar Hamann 22 Gary Speed VORTEX CHROME DIECUT 23 Temuri Ketsbaia PLAYER AND STADIUM MONTAGE V1 Andres Andersson 24 Carl Serrant 73 Player & Stadium Montage V2 Dietmar Hamann 25 Stuart Pearce 74 Player & Stadium Montage V3 Stephane Guivarc’h 26 Steve Watson 75 Player & Stadium Montage V4 Laurent Charvet 27 Alessandro Pistone 76 Player -

Ulusal Ligler Uzantıları

ulusal ligler ve uzantıları 1988-1989 – 1997-1998 erdinç sivritepe turkish-soccer.com 1 dördüncü on yıl Bu on yıllık döneme genel olarak bakılınca ilk göze çarpan şey takımların çeşitli nedenlerle ligleri tamamlayamamaları ve liglerden çekilmeler oluyor. --1. Lig takımı Samsunspor ölümcül trafik kazası nedeni ile sezon sonuna dek izinli sayıldı – 1988-1989 --Cizre terör olayları nedeni ile son yedi maçını oynayamadı ve izinli sayıldı - 1989-1990 --Büyük Salatspor 4. Hafta sonrasında liglerden çekildi - 1989-1990 --Adana Gençlerbirliği 7. Hafta sonrası liglerden çekildi – 1992-1993 --Cizre 15. Hafta sonrası liglerden çekildi – 1993-1994 --TEK 12 Mart 8. Hafta sonrası liglerden çekildi – 1993-1994 --DHMİ ligler başlamadan liglerden çekildi – 1995-1996 --Edirne DSİ ligler başlamadan liglerden çekildi – 1996-1997 --Kozan Belediye ölümcül trafk kazası nedeni ile sezon sonuna dek izinli sayıldı – 1997-1998 1. Lig - Bu dönemde Beşiktaş ve Galatasaray dört, Fenerbahçe iki şampiyonluk elde ederken Trabzonspor şampiyonluk elde edemedi. Galatasaray Fenerbahçe den sonra 10 kez şampiyon olan takım olurken aralarındaki farkı da azalttı. Özel televizyon kanalında maç yayını yapıldı Gece maçları ve Cuma geceleri de maçlar oynanmaya başladı. 2. Lig - Bursaspor genç takımı şampiyon olunca ayni kulübün iki takımının da ayni ligde oynayamaması nedeni ile 1. Lige alınmadı. Genç takımların liglerde oynaması yasaklandı Beş gruplu ve 3 aşamalı lig yapısı denendi ve beğenildi. Bu yapı futbolumuza Play-off yapısını da getirdi 2. Lig takımları Balkan Kupasında oynamaya başladı ancak bu karar kupanın sonlandırılması nedeni ile uzun süreli olmadı 3. Lig - Takım sayıları 130-166 arasında devamlı değişti. Liglerde yepyeni isimler oynamaya başladı 3. Lige Çıkma - Türkiye Amatör Birinciliklerinde dereceye giren takımlar 3.