Accepted Manuscript

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'Black and Whiters': the Relative Powerlessness of 'Active' Supporter

‘Black and whiters’: The relative powerlessness of ‘active’ supporter organization mobility at English Premier League football clubs This article examines the reaction by Newcastle United supporters to the resignation of Kevin Keegan as Newcastle United manager in September 2008. Unhappy at the ownership and management structure of the club following Keegan’s departure, a series of supporter-led meetings took place that led to the creation of Newcastle United Supporters’ Club and Newcastle United Supporters’ Trust. This article draws on a non-participant observation of these meetings and argues that although there are an increasing number of ‘active’ supporters throughout English football, ultimately it is the significant number of ‘passive’ supporters who hamper the inclusion of supporters’ organizations at higher-level clubs. The article concludes by suggesting that clubs, irrespective of wealth and success, need to recognize the long-term value of supporters. Failure to do so can result in fan alienation and ultimately decline (as seen with the recent cases of Coventry City and Portsmouth). Keywords: fans; Premier League; supporter clubs; inclusion; mobilization Introduction Over the last twenty years there have been many changes to English football. In this post- Hillsborough era, the most significant change has been the introduction of a Premier League in 1992 and its growing relationship with satellite television (most notably BSkyB). This global exposure has helped increase the number of sponsors and overseas investors and has -

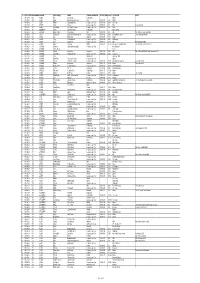

Northumberland and Durham Family History Society Unwanted

Northumberland and Durham Family History Society baptism birth marriage No Gsurname Gforename Bsurname Bforename dayMonth year place death No Bsurname Bforename Gsurname Gforename dayMonth year place all No surname forename dayMonth year place Marriage 933ABBOT Mary ROBINSON James 18Oct1851 Windermere Westmorland Marriage 588ABBOT William HADAWAY Ann 25 Jul1869 Tynemouth Marriage 935ABBOTT Edwin NESS Sarah Jane 20 Jul1882 Wallsend Parrish Church Northumbrland Marriage1561ABBS Maria FORDER James 21May1861 Brooke, Norfolk Marriage 1442 ABELL Thirza GUTTERIDGE Amos 3 Aug 1874 Eston Yorks Death 229 ADAM Ellen 9 Feb 1967 Newcastle upon Tyne Death 406 ADAMS Matilda 11 Oct 1931 Lanchester Co Durham Marriage 2326ADAMS Sarah Elizabeth SOMERSET Ernest Edward 26 Dec 1901 Heaton, Newcastle upon Tyne Marriage1768ADAMS Thomas BORTON Mary 16Oct1849 Coughton Northampton Death 1556 ADAMS Thomas 15 Jan 1908 Brackley, Norhants,Oxford Bucks Birth 3605 ADAMS Sarah Elizabeth 18 May 1876 Stockton Co Durham Marriage 568 ADAMSON Annabell HADAWAY Thomas William 30 Sep 1885 Tynemouth Death 1999 ADAMSON Bryan 13 Aug 1972 Newcastle upon Tyne Birth 835 ADAMSON Constance 18 Oct 1850 Tynemouth Birth 3289ADAMSON Emma Jane 19Jun 1867Hamsterley Co Durham Marriage 556 ADAMSON James Frederick TATE Annabell 6 Oct 1861 Tynemouth Marriage1292ADAMSON Jane HARTBURN John 2Sep1839 Stockton & Sedgefield Co Durham Birth 3654 ADAMSON Julie Kristina 16 Dec 1971 Tynemouth, Northumberland Marriage 2357ADAMSON June PORTER William Sidney 1May 1980 North Tyneside East Death 747 ADAMSON -

P13 2 Layout 1

WEDNESDAY, SEPTEMBER 27, 2017 SPORTS Fleetwood to miss British Ex-Newcastle chairman Las Palmas coach Masters for child’s birth Shepherd dies aged 76 Marquez quits NEWCASTLE: Race to Dubai leader Tommy Fleetwood will miss this week’s LONDON: Former Newcastle chairman Freddy Shepherd, a pivotal BARCELONA: Las Palmas coach Manolo Marquez has become the third British Masters in Newcastle for the possible birth of his child, while figure in the club’s 1990s success, has died aged 76, his family La Liga manager to leave his job this season, calling a surprise news con- Andrew Johnston pulled out injured yesterday. Fleetwood, 26, has elected announced yesterday. Shepherd was Newcastle chairman for 10 years ference yesterday to announce his resignation after losing four of the to stay with his partner and manager Clare, who is soon to give birth to the from 1997 and eventually sold his share of the club to current owner first six games of the campaign. Las Palmas are 15th in the standings couple’s child. “I wanted to give myself every chance of play- Mike Ashley. “Freddy Shepherd sadly passed away peacefully at his with six points and Marquez’s last game in charge was a 2-0 ing this week, but being there at the birth of your child is a home last night,” his family said in a statement. “At this difficult time home defeat by Leganes on Sunday. Marquez had never special moment in anyone’s life and I would not want to the family have asked that their privacy be respected.” Tyneside-born coached a top-flight side before landing the job in July miss it,” said Fleetwood. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses Housing, class and politics: Ashington 1896-1939 Murphy, John Michael How to cite: Murphy, John Michael (1982) Housing, class and politics: Ashington 1896-1939, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/7514/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk HOUSING, CLASS AND POLITICS IN A COMPANY TOWN: ASHINGTON 1896-1939. JOHN MICHAEL MURPHY MASTER OF ARTS DEGREE UNIVERSITY OF DURHAM DEPARTMENT OF SOCIOLOGY AND SOCIAL ADMINISTRATION 1982 The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without his prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged. / \ . - -'./ 25. JAN. 1984 The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Ho quotation from it should be published without his prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged. -

Death in St Jamess Park Free Ebook

FREEDEATH IN ST JAMESS PARK EBOOK Susanna Gregory | 464 pages | 01 Dec 2013 | Little, Brown Book Group | 9780751544336 | English | London, United Kingdom Man arrested on suspicion of murder after body found in London park | UK news | The Guardian With a seating capacity of 52, seats, it is the eighth largest football stadium in England. St James' Park has been the home ground of Newcastle United since and has been used for football since Reluctance to move has led to the distinctive lop-sided appearance of the present-day stadium's asymmetrical stands. Besides club football, St James' Park has also been Death in St Jamess Park for international footballat the Olympics[7] for the rugby league Magic Weekendrugby union World CupPremiership and England Test matches, charity football events, rock concerts, and as a set for Death in St Jamess Park and reality television. The site of St James' Park was originally a patch of sloping grazing land, bordered by Georgian Leazes Terrace, [8] and near the historic Town Moorowned by the Freemen of the city, both factors that later affected development of the ground, with the local council being the landlord of the site. Once the residence of high society in Newcastle, it is now a Grade 1 [9] [10] listed buildingand, recently refurbished, is currently being used as self-catering postgraduate student accommodation by Newcastle University. The first football team to play at St James' Park was Newcastle Rangers in [12] They moved to Death in St Jamess Park ground at Byker inthen returned briefly to St James' Park in before folding that year. -

Northumberland Wills Index 1879 – 1899

ID DATE PROVED PAGE NUMBER SURNAME FIRST NAME[S] ABODE TOWN/VILLAGE/PARISH DATE OF DEATH VALUE OCCUPATION NOTES 1 1898-12-06 693 ABBOT Ann 64,Churchway North Shields Widow 2 1893-08-25 470 ABBOT Sarah Ropery House,Albion Row Byker 1893-07-30 £74 Widow 3 1880-01-13 15 ABBOT William 31,Alexandra Place Newcastle upon Tyne 1879-06-06 £800 Gentleman 4 1892-10-03 814 ABBOTT Henry 33,Close Newcastle upon Tyne 1892-08-23 £31 Miller Amended to £293 5 1890-10-29 763 ABBOTT John William 34,Clayton Street West Newcastle upon Tyne 1889-03-23 £90 Waiter 6 1895-06-10 467 ABERNETHY James 39,Gardener Street North Shields Master Mariner 7 1891-06-10 393 ABSALOM Margaret Dixon Cowpen Quay Blyth 1891-04-30 £30 Wife Wife of Samuel George ABSALOM 8 1879-05-03 337 ADAM George Hall 11,Albert Tce,Westmoreland Rd Newcastle upon Tyne 1879-04-02 £300 Sewing Machine Agent Late of Birmingham,Warwick. 9 1882-09-26 612 ADAMS Ann High St West Wallsend 1882-06-26 £395 Widow 10 1889-07-19 458 ADAMS Henry 209,Westgate Rd Newcastle upon Tyne 1889-06-04 £145 Bar Manager 11 1889-02-16 115 ADAMS Jane 25,Oxford St Newcastle upon Tyne 1889-01-11 £457 Wife Wife of Andrew ADAMS 12 1883-10-18 656 ADAMS Robert 7,Percy Rd Whitley 1883-08-26 £1,189 Innkeeper/Wine/Spirit Merchant Late of 18,East Clayton St,Newcastle 13 1897-03-27 185 ADAMSON Catherine 10,Trinity Chare,Quayside Newcastle upon Tyne Married Woman 14 1895-01-02 001 ADAMSON Charles Murray - - Esquire 15 1892-04-26 401 ADAMSON Hannah Garden House Cullercoats 1891-12-26 £502 Wife Wife of William ADAMSON,Esquire.Amended to -

Vol-12-No-2.Pdf

EDITORIAL I hope you like the Journal's new style front cover. The woodcut by Thomas Bewick, with the oak tree in the foreground, and the castle and the tower of St Nicholas' Church, Newcastle, on one side of the river, and Windmill Hills, Gateshead, on the other, seemed appropriate for our Society. The section of the Journal devoted to Members' Interests and Second Time Around is I know greatly appreciated by many readers; it is however tending to take up more and more space, and I would ask members submitting items for inclusion to keep them as brief as possible - otherwise it may be necessary to impose a limit on the number of words per entry. I am writing this before the first meeting of the Society in London has taken place (at the Society of Genealogists on 4 April), but the indications are that it will be well supported, and that it will lead to the formation of a London Group. Thanks are due to Dr C.T. Watts and Mrs Wendy Bennett for arranging the inaugural meeting; we wish the Group every success. NEWS IN BRIEF Scottish Family History The Department of Adult Education & Extra Mural Studies, University of Aberdeen, is running a Summer School from Saturday 18 July to Saturday 25 July 1987. The course, entitled `Exploring your Family History', is intended for anyone with roots in Scotland. The cost of £165 includes full board in single study bedrooms at Crombie Hall, Old Aberdeen; tuition, notes, maps, etc. ; excursion and entrance costs. Further details may be obtained from the Department of Adult Education & Extra Mural Studies, University of Aberdeen, Taylor Building, ABERDEEN AB9 2UB. -

Ashington – a Proud Past Bright Future Home of the Pitmen Painters

the night away for over half a century. a half over for away night the above ground. above where the town’s residents danced danced residents town’s the where and recreational life life recreational and arcade, with a ballroom above it it above ballroom a with arcade, a thriving cultural cultural thriving a It was built in 1924 as a shopping shopping a as 1924 in built was It spirit which led to to led which spirit iconic, grade II-listed Co-op store. store. Co-op II-listed grade iconic, a community community a you won’t fail to spot the town’s town’s the spot to fail won’t you conditions fostered fostered conditions If you venture along Woodhorn Road Road Woodhorn along venture you If However these these However black diamonds. diamonds. black was based on Ashington’s main street with a roof! a with street main Ashington’s on based was Colliery winning the the winning Colliery upon Tyne and it is said that Sir John Hall’s Metro Centre Centre Metro Hall’s John Sir that said is it and Tyne upon lives at Ashington Ashington at lives largest shopping area between Edinburgh and Newcastle Newcastle and Edinburgh between area shopping largest 300 miners lost their their lost miners 300 ballrooms. Indeed Ashington was once described as the the as described once was Ashington Indeed ballrooms. dangerous - nearly nearly - dangerous several department stores, five cinemas, theatres and and theatres cinemas, five stores, department several dirty, dusty and and dusty dirty, population. At one time the town centre could boast boast could centre town the time one At population. -

La Ck & W Hite K Nig Ht

HARRY DE COSEMO DE HARRY HARRY DE COSEMO ‘Detailed, insightful and heartwarming, this book captures the very essence of Sir Bobby Robson the manager and, more importantly, the man.’ Black Chris Waugh, The Athletic. Black & White Knight & White Black & White Knight How Sir Bobby Robson Made Newcastle United Again Foreword by George Caulkin Contents Foreword by George Caulkin 7 Acknowledgements 11 Introduction 15 1. Sliding Doors 19 2 The Kindest Man 46 3. Laying The Groundwork 70 4. Reaching The Next Level 93 5. Christmas Number One 118 6 The History Boys 140 7. Magic In Milan 169 8 Cracks Begin To Show 189 9. The Summer Of Discontent 222 10 The Cruellest Cut 242 11. Managing A Team Again 264 Bibliography 285 Chapter 1 Sliding Doors ‘Things were moving at last. The North East was calling me back. I was on my way home’ – Bobby Robson RAIN WAS lashing down hard; the heavens had opened over St James’ Park and finally put out the dwindling fire that was Ruud Gullit’s tenure as manager at Newcastle United The mood was mutinous This famous stadium, sat atop a hill in the city, was a place where dreams almost came true three years earlier Newcastle harnessed the power of unity and, led by Kevin Keegan, a man who understood exactly what it took to guide the club, narrowly missed out on the Premiership title Football is a religion in the area; it can be a force to achieve spectacular things But that was in the past and difficult years followed The whole club had never been so divided in its modern history, and they were only heading one way: down