Defending the Human Right to Life in Latin America

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

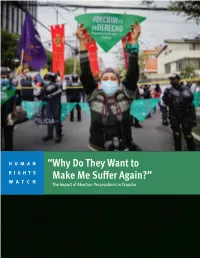

“Why Do They Want to Make Me Suffer Again?” the Impact of Abortion Prosecutions in Ecuador

HUMAN “Why Do They Want to RIGHTS WATCH Make Me Suffer Again?” The Impact of Abortion Prosecutions in Ecuador “Why Do They Want to Make Me Suffer Again?” The Impact of Abortion Prosecutions in Ecuador Copyright © 2021 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-62313-919-3 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch defends the rights of people worldwide. We scrupulously investigate abuses, expose the facts widely, and pressure those with power to respect rights and secure justice. Human Rights Watch is an independent, international organization that works as part of a vibrant movement to uphold human dignity and advance the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org JULY 2021 ISBN: 978-1-62313-919-3 “Why Do They Want to Make Me Suffer Again?” The Impact of Abortion Prosecutions in Ecuador Summary ........................................................................................................................... 1 Key Recommendations ....................................................................................................... 8 To the Presidency ................................................................................................................... -

13 Las Elecciones Subnacionales De 2015 En

Revista Uruguaya de Ciencia Política - Vol. 25 N°1 - ICP - Montevideo 13 LAS ELECCIONES SUBNACIONALES DE 2015 EN ARGENTINA: ESTABILIDAD CON CAMBIO* 2015 Subnational Elections in Argentina: Stability with Change Natalia Del Cogliano** y Carlos Varetto*** Resumen: El presente artículo explora las principales características del extenso año electoral que vivió Ar- gentina a lo largo de 2015 para demostrar que la excepcionalidad del proceso no estuvo tanto en la magnitud del cambio en el orden subnacional, sino en la significancia para la política nacional de unos pocos hechos en ciertas provincias. Se analizan las elecciones de orden subnacional, buscando realizar una lectura dinámica que incorpore el plano de la carrera por la Presidencia de la Nación, sin el cual el análisis electoral subnacio- nal resultaría insuficiente. A tal fin, en primer lugar se presentan las características del complejo federalismo electoral, y la dinámica de desdoblamiento del calendario electoral, los cuales constituyen importantes retos para la coordinación de las élites y del electorado. Seguidamente, se realiza una sintética descripción del desarrollo de los sistemas políticos provinciales argentinos utilizando una serie de indicadores de sistemas de partidos. Finalmente, se hace una lectura del año electoral en su dimensión fundamentalmente subnacional a partir de cuatro hitos centrales, y se concluye subrayando la centralidad en la definición de la política nacio- nal de las provincias que constituyen la zona núcleo de producción agropecuaria del país. Palabras clave: elecciones, Argentina, política subnacional, calendario electoral Abstract: The paper explores the main features of the long electoral year that took place in Argentina during 2015. It aims to demonstrate that the main feature of the electoral process was not so much the magnitude of the political change in the subnational level, but the relevance of the electoral outcomes in a few districts for national politics. -

Annual Technical Report 2015

Annual technical report 2015 Department of Reproductive Health and Research UNDP/UNFPA/UNICEF/WHO/World Bank Special Programme of Research, Development and Research Training in Human Reproduction (HRP) 2015 For more information, please contact: Department of Reproductive Health and Research World Health Organization Avenue Appia 20, CH-1211 Geneva 27, Switzerland Fax: +41 22 791 4171 E-mail: [email protected] www.who.int/reproductivehealth Department of Reproductive Health and Research, including the UNDP/UNFPA/UNICEF/WHO/World Bank Special Programme of Research, Development and Research Training in Human Reproduction (HRP) Annual Technical Report, 2015 WHO/RHR/HRP/16.08 UNDP/UNFPA/UNICEF/WHO/World Bank Special Programme of Research, Development and Research Training in Human Reproduction (HRP). Annual Technical Report 2015 © World Health Organization 2016 All rights reserved. Publications of the World Health Organization are available on the WHO website (www.who.int) or can be purchased from WHO Press, World Health Organization, 20 Avenue Appia, 1211 Geneva 27, Switzerland (tel.: +41 22 791 3264; fax: +41 22 791 4857; e-mail: [email protected]). Requests for permission to reproduce or translate WHO publications –whether for sale or for non-com- mercial distribution– should be addressed to WHO Press through the WHO website (www.who.int/about/ licensing/copyright_ form/en/index.html). The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the World Health Organization concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

Abortion and the Law in New

NSW PARLIAMENTARY LIBRARY RESEARCH SERVICE Abortion and the law in New South Wales by Talina Drabsch Briefing Paper No 9/05 ISSN 1325-4456 ISBN 0 7313 1784 X August 2005 © 2005 Except to the extent of the uses permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part of this document may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means including information storage and retrieval systems, without the prior written consent from the Librarian, New South Wales Parliamentary Library, other than by Members of the New South Wales Parliament in the course of their official duties. Abortion and the law in New South Wales by Talina Drabsch NSW PARLIAMENTARY LIBRARY RESEARCH SERVICE David Clune (MA, PhD, Dip Lib), Manager..............................................(02) 9230 2484 Gareth Griffith (BSc (Econ) (Hons), LLB (Hons), PhD), Senior Research Officer, Politics and Government / Law .........................(02) 9230 2356 Talina Drabsch (BA, LLB (Hons)), Research Officer, Law ......................(02) 9230 2768 Lenny Roth (BCom, LLB), Research Officer, Law ...................................(02) 9230 3085 Stewart Smith (BSc (Hons), MELGL), Research Officer, Environment ...(02) 9230 2798 John Wilkinson (MA, PhD), Research Officer, Economics.......................(02) 9230 2006 Should Members or their staff require further information about this publication please contact the author. Information about Research Publications can be found on the Internet at: www.parliament.nsw.gov.au/WEB_FEED/PHWebContent.nsf/PHPages/LibraryPublications Advice on -

Revista-07.Pdf

AUTORIDADES Dra. Cristina Fernández de Kirchner Presidenta de la Nación Lic. Amado Boudou Vicepresidente de la Nación Cdor. Jorge Milton Capitanich Jefe de Gabinete de Ministros Dra. María Matilde Morales Secretaria Ejecutiva Consejo Nacional de Coordinación de Políticas Sociales Arq. D. Julio De Vido Ministro de Planificación Federal, Inversión Pública y Servicios Dr. Alberto Sileoni Ministro de Educación Dr. Carlos Tomada Ministro de Trabajo, Empleo y Seguridad Social Juan Luis Manzur Ministro de Salud Dra. Da. Alicia Kirchner Ministra de Desarrollo Social Ing. Agr. Carlos Casamiquela Ministro de Agricultura, Ganadería y Pesca Dr. Daniel Reposo Síndico General de la Nación Dr. Eduardo Omar Gallo Síndico General Adjunto Dr. Agustín Carlos A. Tarelli Síndico General Adjunto Revista SIGEN SUMARIO Año 5 / Nº 7 / Noviembre 2014 Staff 02. Editorial Director Dr. Daniel G. Reposo 04. ¿Qué es la Red Federal de Control Público? Subdirectores Dr. Agustín A. Tarelli Dr. Eduardo O. Gallo 09. Breve historia Comité Editorial 13. Fortalezas, Objetivos y Resultados Cr. Marcelo Cainzos Cr. Alejandro Díaz Dra. María Isabel Fimognare 15. Decreto 38 / 2014 Cra. Miriam Lariguet Ing. Fernando Mollo Ing. Arturo Papazián 2014, el año en que el Gobierno Nacional destacó la labor de la Dra. María E. Rodríguez Greno 20. Dr. Agustín Tarelli Red Federal de Control Público Cr. Arturo Zaera 26. El Secretariado Permanente de Tribunales de Cuentas en la Coordinación Periodística Red Federal de Control Público Lic. Jorge Laprovitta Paola Busti 29. El Tribunal de Cuentas de Tucumán en la Red Federal de Paola Abatto Valsamakis Control Público Coordinación de Diseño y 33. Red Federal de Control Público a diez años de su creación Producción Gráfica Roberto Cappa 35. -

Master Document Template

Copyright by Katherine Schlosser Bersch 2015 The Dissertation Committee for Katherine Schlosser Bersch Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: When Democracies Deliver Governance Reform in Argentina and Brazil Committee: Wendy Hunter, Co-Supervisor Kurt Weyland, Co-Supervisor Daniel Brinks Bryan Jones Jennifer Bussell When Democracies Deliver Governance Reform in Argentina and Brazil by Katherine Schlosser Bersch, B.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin August 2015 Acknowledgements Many individuals and institutions contributed to this project. I am most grateful for the advice and dedication of Wendy Hunter and Kurt Weyland, my dissertation co- supervisors. I would also like to thank my committee members: Daniel Brinks, Bryan Jones, and Jennifer Bussell. I am particularly indebted to numerous individuals in Brazil and Argentina, especially all of those I interviewed. The technocrats, government officials, politicians, auditors, entrepreneurs, lobbyists, journalists, scholars, practitioners, and experts who gave their time and expertise to this project are too many to name. I am especially grateful to Felix Lopez, Sérgio Praça (in Brazil), and Natalia Volosin (in Argentina) for their generous help and advice. Several organizations provided financial resources and deserve special mention. Pre-dissertation research trips to Argentina and Brazil were supported by a Lozano Long Summer Research Grant and a Tinker Summer Field Research Grant from the University of Texas at Austin. A Boren Fellowship from the National Security Education Program funded my research in Brazil and a grant from the University of Texas Graduate School provided funding for research in Argentina. -

Global Justice Center

Submission to the Committee against Torture in relation to its examination of the United States of America’s Third to Fifth State Party Report The United States’ Abortion Restrictions on Foreign Assistance Deny Safe Abortion Services to Women and Girls Raped in Armed Conflict November 2014 2 United States: GJC & OMCT Submission to the Committee against Torture Table of Contents I. Executive Summary................................................................................................................... 3 II. Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 4 III. The Organizations Submitting this Report ....................................................................... 6 IV. US Abortion Restrictions on Foreign Assistance ............................................................ 7 V. Denial of Abortions Causes Severe Physical and Mental Pain and Suffering ........ 9 VI. Growing International Recognition that War Rape Victims Require Abortion Services and that the Denial of Abortion Constitutes Torture or Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment ....................................................................................................... 12 VII. US Responsibility to Prevent Torture and Ill-Treatment .......................................... 14 VIII. The Denial of Abortion Services to War Rape Victims is Discriminatory ............ 16 IX. US Abortion Restrictions Deny Rehabilitation from Rape ....................................... -

Abortion Facts and Figures 2021

ABORTION FACTS & FIGURES 2021 ABORTION FACTS & FIGURES TABLE OF CONTENTS PART ONE Introduction . 1 Global Overview . 2 African Overview . 4 By the Numbers . 6 Maternal Health . .9 Safe Abortion . 11 Unsafe Abortion . 13 Post-Abortion Care . 15 Contraception . 17 Unmet Need for Family Planning . 22 Abortion Laws and Policies . 24. PART TWO Glossary . 28 Appendix I: International Conventions . 30. Appendix II: How Unsafe Abortions Are Counted . 32 Appendix III: About the Sources . .33 Regional Data for Africa . 34 Regional Data for Asia . 44 Regional Data for Latin America and the Caribbean . 54. POPULATION REFERENCE BUREAU Population Reference Bureau INFORMS people around the world about population, health, and the environment, and EMPOWERS them to use that information to ADVANCE the well-being of current and future generations . This guide was written by Deborah Mesce, former PRB program director, international media training . The graphic designer was Sean Noyce . Thank you to Alana Barton, director of media programs; AÏssata Fall, senior policy advisor; Charlotte Feldman-Jacobs, former associate vice president; Kate P . Gilles, former program director; Tess McLoud, policy analyst; Cathryn Streifel, senior policy advisor; and Heidi Worley, senior writer; all at PRB, for their inputs and guidance . Thank you as well to Anneka Van Scoyoc, PRB senior graphic designer, for guiding the design process . © 2021 Population Reference Bureau . All rights reserved . This publication is available in print and on PRB’s website . To become a PRB member or to order PRB materials, contact us at: 1875 Connecticut Ave ., NW, Suite 520 Washington, DC 20009-5728 PHONE: 1-800-877-9881 E-MAIL: communications@prb .org WEB: www .prb .org For permission to reproduce parts of this publication, contact PRB at permissions@prb org. -

Maestría En Administración Y Políticas Públicas

Maestría en Administración y Políticas Públicas Universidad de San Andrés Décimo primera promoción Tesis de graduación Jugar con fuego Intereses y vetos de los actores en la definición de la regulación nacional de control de tabaco en la Argentina Pablo S. Cattoni N° de legajo: DNI0026420654 Director: Diego Reynoso Buenos Aires, 24 de marzo de 2019 1 Maestría en Administración y Políticas Públicas Universidad de San Andrés Décimo primera promoción Tesis de graduación Jugar con fuego Intereses y vetos de los actores en la definición de la regulación nacional de control de tabaco en la Argentina Pablo S. Cattoni N° de legajo: DNI0026420654 Director: Diego Reynoso Buenos Aires, 24 de marzo de 2019 1 A mis noctilucas, causa y consecuencia de este trabajo. 2 Mi abuelita, que Dios tenga en su gloria, decía siempre: -Hay que ser Belcebú para vencer a Satanás. Carlos Fuentes La Silla del Águila 3 Sumario En los últimos años una gran cantidad de países del mundo han avanzado en la regulación de la producción, el consumo, la comercialización y la publicidad de productos de tabaco. La República Argentina, por su parte, demoró durante años la adopción de una acción concreta, decidida y adecuada del Estado Nacional para abordar la problemática de los efectos que genera el consumo de cigarrillos en el país. Recién con la sanción de la ley Nº 26.687, en junio de 2011 y luego de varios años de discusión, pudo alinearse con las tendencias internacionales, al establecer la prohibición de la publicidad masiva de productos elaborados con tabaco, la obligación de incluir mensajes de advertencia en los paquetes de cigarrillos y la definición de limitaciones al consumo de cigarrillos en espacios privados de acceso público, entre otras cuestiones. -

Monitor Nacional Imagen Agosto/18

Centro de Análisis e Investigación MONITOR NACIONAL DE IMAGEN GOBERNADORES Y POLITICOS agosto 2018 IMAGEN GOBERNADORES ¿Qué imagen tiene de María Eugenia Vidal? POSITIVA NEGATIVA 47,9% 45,9% 31,5 32,8 16,4 13,1 6,2 Muy buena Buena Mala Muy mala No sabe Sexo Edad Nivel Educativo Zona Hipótesis electoral ‘19 50 M F 16-29 30-49 P S U AMBA INTERIOR CONT. CAMB. NS y más Positiva 48,4 52,8 44,9 46,6 63,6 50,9 49,5 51,6 41,6 59,5 90,1 21,4 47,3 Negativa 47,9 44,0 50,7 49,9 34,3 42,8 46,9 45,9 56,3 35,8 7,5 75,6 39,9 No sabe 3,7 3,2 4,4 3,5 2,0 6,3 3,6 2,5 2,1 4,7 2,4 3,1 12,8 ¿Qué imagen tiene de Juan Luis Manzur, gobernador de Tucumán? POSITIVA NEGATIVA 19,6% 49,8% 30,6 25,8 24,1 17,0 2,5 Muy buena Buena Mala Muy mala No sabe Sexo Edad Nivel Educativo Zona Hipótesis electoral ‘19 50 M F 16-29 30-49 P S U AMBA INTERIOR CONT. CAMB. NS y más Positiva 18,7 20,4 18,7 17,7 23,2 29,2 20,2 16,3 18,1 21,1 23,9 16,4 18,9 Negativa 55,9 44,0 50,2 48,4 51,3 46,1 47,6 52,8 52,2 47,5 44,1 55,7 37,8 No sabe 25,4 35,6 31,0 33,9 25,5 24,8 32,2 30,9 29,7 31,4 32,0 27,9 43,3 ¿Qué imagen tiene de Lucía Corpacci, gobernadora de Catamarca? POSITIVA NEGATIVA 17,9% 33,1% 49,0 15,7 17,6 15,5 2,2 Muy buena Buena Mala Muy mala No sabe Sexo Edad Nivel Educativo Zona Hipótesis electoral ‘19 50 M F 16-29 30-49 P S U AMBA INTERIOR CONT. -

Northern Ireland Barriers to Accessing Abortion Services

NORTHERN IRELAND BARRIERS TO ACCESSING ABORTION SERVICES Amnesty International Publications First published in 2015 by Amnesty International Publications International Secretariat Peter Benenson House 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW United Kingdom www.amnesty.org © Amnesty International Publications 2015 Index: EUR 45/0157/2015 Original Language: English Printed by Amnesty International, International Secretariat, United Kingdom All rights reserved. This publication is copyright, but may be reproduced by any method without fee for advocacy, campaigning and teaching purposes, but not for resale. The copyright holders request that all such use be registered with them for impact assessment purposes. For copying in any other circumstances, or for reuse in other publications, or for translation or adaptation, prior written permission must be obtained from the publishers, and a fee may be payable. To request permission, or for any other inquiries, please contact [email protected] Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 3 million supporters, members and activists in more than 150 countries and territories who campaign to end grave abuses of human rights. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. CONTENTS Executive summary ...................................................................................................... -

TURBULENCIA ECONÓMICA, POLARIZACIÓN SOCIAL Y REALINEAMIENTO POLÍTICO Revista De Ciencia Política, Vol

Revista de Ciencia Política ISSN: 0716-1417 [email protected] Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile Chile DE LUCA, MIGUEL; MALAMUD, ANDRÉS ARGENTINA: TURBULENCIA ECONÓMICA, POLARIZACIÓN SOCIAL Y REALINEAMIENTO POLÍTICO Revista de Ciencia Política, vol. 30, núm. 2, 2010, pp. 173-189 Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile Santiago, Chile Disponible en: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=32416605001 Cómo citar el artículo Número completo Sistema de Información Científica Más información del artículo Red de Revistas Científicas de América Latina, el Caribe, España y Portugal Página de la revista en redalyc.org Proyecto académico sin fines de lucro, desarrollado bajo la iniciativa de acceso abierto REVISTA DE CIENCIA POLÍTICA / VOLUMEN 30 / Nº 2 / 2010 / 173 – 189 ARGENTIN A : TURBULENCI A ECONÓMIC A , POL A RIZ A CIÓN SOCI A L Y RE A LINE A MIENTO POLÍTICO Argentina: Economic Turbulence, Social Polarization and Political Realignment Artículos MIGUEL DE LUCA CIENCIA Universidad de Buenos Aires-CONICET POLÍTICA ANDRÉS MALAMUD Universidad de Lisboa, Instituto de Ciencias Sociales RESUMEN El resultado de las elecciones parlamentarias de 2009 abrió un panorama complejo y difícil para la presidenta Cristina Fernández de Kirchner. Al obtener un tercio de los votos emitidos, perdió el control de la Cámara de Diputados por decisión de los electores y, más tarde, el del Senado por divisiones en su propia coalición. La crispación social generada por el gobierno contribuyó a aglutinar a la oposición, previamente fragmentada, en dos alianzas electorales cuyo arraigo territorial complementario les permitió vencer al oficialismo en los principales distritos. La economía se resintió por la crisis global y por los desmanejos locales; aunque el colapso se evitó, la fragilidad fiscal persiste por la dificultad del gobierno para obtener financiamiento.