Derek Allen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SHORT-TERM EFFECTS of SPRINGTIME PRESCRIBED FIRES on ADULT POPULATIONS of SOIL-EMERGING WEEVILS in CENTRAL APPALACHIAN HARDWOOD STANDS David P

SHORT-TERM EFFECTS OF SPRINGTIME PRESCRIBED FIRES ON ADULT POPULATIONS OF SOIL-EMERGING WEEVILS IN CENTRAL APPALACHIAN HARDWOOD STANDS David P. McGann, David W. McGill, Thomas M. Sehuler, and W Mark Ford' Absmct-Numerous biotic and abtotic factors Interact to affect oak regeneration in the central Appalachians. F~re,whtte- tailed deer, rodents, other vertebrate seed predators, inmlve plants, Insects, fungi, climate, and tree physrology contribute singularly or addit~velyto oak regeneration problems. Moreaver, fire suppressron has signifi~antlyenhanced the deleter~ous impacts of several of these brotrc tnfluences. The relattonshrp between fire and acorn werrJils IS unknom, but acorn weevils are significant contributors to regeneraon problems in some oak stands and may be vuineraMe to fire at certain life stages. As part of a broader tnvest~gationof ftre use as a silvicuitural tool, we examined presctibed fire impacts on acorn weevils (genera: Cumuiio and Conotractieius)that inhibit oak (Quemus spp.! regeneration by lam! consumption of embryonic or newly dropped acorns. We prescribe burned two stands on the Fernow Experimental Forest in north-central West Virginia: One was burned April, 2002, and the other Aprii, 2003. We placed soil emergence traps under oak and other tree species on five plots within each burn treatment and four adjacent unburned plots. Arthropod samples were collected April to October in 2003 and 2004. We collected 233 weevils representing 11 species from 9 genera. CuwIio and Cyrtepistomus species predominated; Gono~chelusspecies were notable. Our preliminary data indicates that acorn weevil emergence may not be reduced following a stngle spring fire. Herein, we describe the pattern and intensity of acorn weevil emergence during the first 2 years of our study. -

Abacca Mosaic Virus

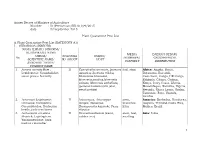

Annex Decree of Ministry of Agriculture Number : 51/Permentan/KR.010/9/2015 date : 23 September 2015 Plant Quarantine Pest List A. Plant Quarantine Pest List (KATEGORY A1) I. SERANGGA (INSECTS) NAMA ILMIAH/ SINONIM/ KLASIFIKASI/ NAMA MEDIA DAERAH SEBAR/ UMUM/ GOLONGA INANG/ No PEMBAWA/ GEOGRAPHICAL SCIENTIFIC NAME/ N/ GROUP HOST PATHWAY DISTRIBUTION SYNONIM/ TAXON/ COMMON NAME 1. Acraea acerata Hew.; II Convolvulus arvensis, Ipomoea leaf, stem Africa: Angola, Benin, Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae; aquatica, Ipomoea triloba, Botswana, Burundi, sweet potato butterfly Merremiae bracteata, Cameroon, Congo, DR Congo, Merremia pacifica,Merremia Ethiopia, Ghana, Guinea, peltata, Merremia umbellata, Kenya, Ivory Coast, Liberia, Ipomoea batatas (ubi jalar, Mozambique, Namibia, Nigeria, sweet potato) Rwanda, Sierra Leone, Sudan, Tanzania, Togo. Uganda, Zambia 2. Ac rocinus longimanus II Artocarpus, Artocarpus stem, America: Barbados, Honduras, Linnaeus; Coleoptera: integra, Moraceae, branches, Guyana, Trinidad,Costa Rica, Cerambycidae; Herlequin Broussonetia kazinoki, Ficus litter Mexico, Brazil beetle, jack-tree borer elastica 3. Aetherastis circulata II Hevea brasiliensis (karet, stem, leaf, Asia: India Meyrick; Lepidoptera: rubber tree) seedling Yponomeutidae; bark feeding caterpillar 1 4. Agrilus mali Matsumura; II Malus domestica (apel, apple) buds, stem, Asia: China, Korea DPR (North Coleoptera: Buprestidae; seedling, Korea), Republic of Korea apple borer, apple rhizome (South Korea) buprestid Europe: Russia 5. Agrilus planipennis II Fraxinus americana, -

Durio Zibethinus

1 The Draft Genome of Tropical Fruit Durian (Durio zibethinus) 2 1,2,3,4,5,6# 2,7 2,7 3 3 Bin Tean Teh , Kevin Lim *, Chern Han Yong *, Cedric Chuan Young Ng *, Sushma Ramesh 8,14,15,16 3 2,4, 7 9 10 4 Rao , Vikneswari Rajasegaran , Weng Khong Lim , Choon Kiat Ong , Ki Chan , Vincent Kin 11 12 8,14,15,16,17 2,4,7 13 5 Yuen Cheng , Poh Sheng Soh , Sanjay Swarup , Steven G Rozen , Niranjan Nagarajan , 1,2,4,5,13# 6 Patrick Tan 7 8 1 9 Thorn Biosystems Pte Ltd, Singapore 2 10 Program in Cancer and Stem Cell Biology, Duke-NUS Medical School, Singapore 3 11 Laboratory of Cancer Epigenome, Division of Medical Science, National Cancer Centre, Singapore 4 12 SingHealth/Duke-NUS Institute of Precision Medicine, National Heart Centre, Singapore 5 13 Cancer Science Institute of Singapore, National University of Singapore, Singapore 6 14 Institute of Molecular and Cellular Biology, Singapore 7 15 Centre for Computational Biology, Duke-NUS Medical School, Singapore 8 16 Department of Biological Sciences, National University of Singapore, Singapore 9 17 Lymphoma Genomic Translational Research Laboratory, National Cancer Centre, Singapore 10 18 Global Databank, Singapore 11 19 Verdant Foundation, Hong Kong 12 20 Samsoney Group, Malaysia 13 21 Genome Institute of Singapore, Singapore 14 22 Singapore Centre for Environmental Life Sciences Engineering, Nanyang Technological University, 23 Singapore 15 24 Metabolites Biology Lab, National University of Singapore, Singapore 16 25 NUS Synthetic Biology for Clinical and Technological Innovation, Life Sciences Institute, National 26 University of Singapore, Singapore 17 27 NUS Environmental Research Institute, National University of Singapore, Singapore 28 29 30 * Denotes equal contribution 31 32 # Address correspondence: [email protected] (B.T.T.) or [email protected] 33 (P.T.) 34 2 35 Abstract 36 Durian (Durio zibethinus) is a South East Asian tropical plant species, well-known for its hefty spine- 37 covered fruit and notorious sulfury and onion-like odor. -

Food and Foraging Preferences of Three Pteropodid Bats in Southern India

JoTT COMMUNI C ATION 4(1): 2295–2303 Food and foraging preferences of three pteropodid bats in southern India M.R. Sudhakaran 1 & Paramanantha Swami Doss 2 1 Department of Advanced Zoology and Biotechnology, Sri Paramakalyani College, Alwarkurichi, Tamil Nadu 627412, India 2 Department of Animal Behaviour and Physiology, Madurai Kamaraj University, Madurai, Tamil Nadu 625021, India Email: 1 [email protected] (corresponding author), 2 [email protected] Date of publication (online): 26 January 2012 Abstract: A study on the food, foraging and flight height in three species of pteropodid Date of publication (print): 26 January 2012 bats, namely Cynopterus sphinx, Rousettus leschenaultii and Pteropus giganteus was ISSN 0974-7907 (online) | 0974-7893 (print) conducted in Tirunelveli and Tuticorin districts of southern Tamil Nadu, India. A total of 37 species of plants were identified as potential food plants of the pteropodid bats. Editor: C. Srinivasulu The preference for fruits by pteropodids varied according to the developmental stages Manuscript details: of fruits namely, immature, unripe and ripe. There is a relationship between the forag- Ms # o2227 ing activities of bats and the moon phase. Bats exhibit a varied foraging pattern and Received 02 June 2009 flight height. A variation in the foraging flight height was observed in C. sphinx and R. Final received 19 July 2011 leschenaultii. R. leschenaultii was observed to have a higher foraging echelon than that Finally accepted 20 December 2011 of the C. sphinx. In our study we found that the C. sphinx forages normally at canopy level (up to 3.5m), R. leschenaultii forages at upper canopy levels (up to 9m) and P. -

Pouteria Sapota

Pouteria sapota Pouteria sapota, mamey sapote, is a species of tree na- propagated by grafting, which ensures the new plant has tive to Central America, naturally ranging from southern the same characteristics as the parent, especially its fruit. Mexico to southern Costa Rica. Today, the tree is cul- It is also considerably faster than growing trees by seed. tivated not only in Mexico, but also in Central America, The leaves are pointed at both ends, 4 to 12 inches in the Caribbean, and South Florida for its fruit, which is length and grow in clusters at the ends of branches. commonly eaten in many Latin American countries. It has different names depending on the country: mamey The fruit is about 10 to 25 cm (4 to 10 inches) long and (Cuba), zapote colorado (Costa Rica), níspero and zapote 8 to 12 cm (3 to 5 inches) wide and has flesh ranging in rojo (South America), among others. color from pink to orange to red. The brown skin has a texture somewhat between sandpaper and the fuzz on a peach. The fruit’s texture is creamy and soft. A mamey 1 Description sapote is ripe when the flesh is pink when a fleck of the skin is removed. The flesh should give slightly, as with a ripe kiwifruit. The mamey sapote is related to other sapotes such as sapodilla (Manilkara zapota), abiu (P. caimito) and canistel (P. campechiana), but unrelated to the black sapote (Diospyros digyna) and white sapote (Casimiroa edulis).[2] It should not be confused with the mammee ap- ple (Mammea americana). -

ZAPOTE the Popular Name Represents Many Diverse Edible Fruits of Guatemala

Sacred Animals and Exotic Tropical Plants monzón sofía photo: by Dr. Nicholas M. Hellmuth and Daniela Da’Costa Franco, FLAAR Reports ZAPOTE The popular name represents many diverse edible fruits of Guatemala ne of the tree fruits raised by the Most zapotes have a soft fruit inside and Maya long ago that is still enjoyed a “zapote brown” covering outside (except today is the zapote. Although for a few that have other external colors). It Othere are several fruits of the same name, the is typical for Spanish nomenclature of fruits popular nomenclature is pure chaos. Some of and flowers to be totally confusing. Zapote is the “zapote” fruits belong to the sapotaceae a vestige of the Nahuatl (Aztec) word tzapotl. family and all are native to Mesoamerica. The first plant on our list, Manilkara But other botanically unrelated fruits are also zapote, is commonly named chicozapote. called zapote/sapote; some are barely edible This is one of the most appreciated edible (such as the zapotón). There are probably species because of its commercial value. It even other zapote-named fruits that are not is distributed from the southeast of Mexico, all native to Mesoamerica. especially the Yucatán Peninsula into Belize 60 Dining ❬ ANTIGUA and the Petén area, where it is occasionally now collecting pertinent information related an abundant tree in the forest. The principal to the eating habits of Maya people, and all products of these trees are the fruit; the the plants they used and how they used them latex, which is used as the basis of natural for food. -

A History of Fruits on the Southeast Asian Mainland

OFFPRINT A history of fruits on the Southeast Asian mainland Roger Blench Kay Williamson Educational Foundation Cambridge, UK E-mail: [email protected] http://www.rogerblench.info/RBOP.htm Occasional Paper 4 Linguistics, Archaeology and the Human Past Edited by Toshiki OSADA and Akinori UESUGI Indus Project Research Institute for Humanity and Nature, Kyoto, Japan 2008 ISBN 978-4-902325-33-1 A history of Fruits on the Southeast Asian mainland A history of fruits on the Southeast Asian mainland Roger Blench Kay Williamson Educational Foundation Cambridge, UK E-mail: [email protected] http://www.rogerblench.info/RBOP.htm ABSTRACT The paper presents an overview of the history of the principal tree fruits grown on the Southeast Asian mainland, making use of data from biogeography, archaeobotany, iconography and linguistics. Many assertions in the literature about the origins of particular species are found to be without empirical basis. In the absence of other data, comparative linguistics is an important source for tracing the spread of some fruits. Contrary to the Pacific, it seems that many of the fruits we now consider characteristic of the region may well have spread in recent times. INTRODUCTION empirical base for Pacific languages is not matched for mainland phyla such as Austroasiatic, Daic, Sino- This study 1) is intended to complement a previous Tibetan or Hmong-Mien, so accounts based purely paper on the history of tree-fruits in island Southeast on Austronesian tend to give a one-sided picture. Asia and the Pacific (Blench 2005). Arboriculture Although occasional detailed accounts of individual is very neglected in comparison to other types of languages exist (e.g. -

Much Like the Oil Farms of the Last Century Were

A CONTEMPORARY USE FOR A HISTORIC ENERGY SOURCE Kenneth C. Wolensky with photographs by Don Giles uch like the oil farms of the last century were for drillers and riggers, Pennsylvania’s wind farms are M proving grounds for engineers and technicians as they harness wind power. The long-standing use of wind power that for centuries propelled sailing vessels has been transformed throughout the world to produce electricity. Farmers used wind power in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries to pump water, grind grain, and, sometimes, generate electricity. And Pennsylvania was no exception. PHMC staff photographer Don Giles captured both the symmetrical beauty and implications for Pennsylvania’s energy future at Locust Ridge Wind Farm, straddling Schuylkill and Columbia counties. PHMC STATE MUSEUM OF PENNSYLVANIA/PHOTO BY DON GILES 66 PENNSYLVANIAPENNSYLVANIA HERITAGEHERITAGE FallFall 20092009 www.paheritage.orgwww.paheritage.org www.phmc.state.pa.uswww.phmc.state.pa.us PENNSYLVANIAPENNSYLVANIA HERITAGEHERITAGE FallFall 20092009 77 Lancaster County inventor David Herr Bausman (1864–1911) fuels led to advancements in wind technology and turbines, patented a windmill in March 1885 and designed four models particularly in the western world. In 2008, the United States between 1884 and 1900, which were erected on farms in generated more electricity from wind turbines than Germany: a Pennsylvania. The son of a Pennsylvania German farmer, total of 25,000 megawatts (MW). (A megawatt is equal to one Bausman was twenty-one when he submitted his first drawings million watts; a watt is equal to one joule of energy per for what he called a “Wind Engine” to the United States Patent second.) Wind turbines in the United States produce enough Office (now the United States Patent and Trademark office). -

Outline of Angiosperm Phylogeny

Outline of angiosperm phylogeny: orders, families, and representative genera with emphasis on Oregon native plants Priscilla Spears December 2013 The following listing gives an introduction to the phylogenetic classification of the flowering plants that has emerged in recent decades, and which is based on nucleic acid sequences as well as morphological and developmental data. This listing emphasizes temperate families of the Northern Hemisphere and is meant as an overview with examples of Oregon native plants. It includes many exotic genera that are grown in Oregon as ornamentals plus other plants of interest worldwide. The genera that are Oregon natives are printed in a blue font. Genera that are exotics are shown in black, however genera in blue may also contain non-native species. Names separated by a slash are alternatives or else the nomenclature is in flux. When several genera have the same common name, the names are separated by commas. The order of the family names is from the linear listing of families in the APG III report. For further information, see the references on the last page. Basal Angiosperms (ANITA grade) Amborellales Amborellaceae, sole family, the earliest branch of flowering plants, a shrub native to New Caledonia – Amborella Nymphaeales Hydatellaceae – aquatics from Australasia, previously classified as a grass Cabombaceae (water shield – Brasenia, fanwort – Cabomba) Nymphaeaceae (water lilies – Nymphaea; pond lilies – Nuphar) Austrobaileyales Schisandraceae (wild sarsaparilla, star vine – Schisandra; Japanese -

List of the Import Prohibited Plants

List of the Import Prohibited Plants The Annexed Table 2 of the amended Enforcement Ordinance of the Plant Protection Law (Amended portions are under lined) Districts Prohibited Plants Quarantine Pests 1. Yemen, Israel, Saudi Arabia, Fresh fruits of akee, avocado, star berry, Mediterranean fruit fly Syria, Turkey, Jordan, Lebanon, allspice, olive, cashew nut, kiwi fruit, Thevetia (Ceratitis capitata) Albania, Italy, United Kingdom peruviana, carambola, pomegranate, jaboticaba, (Great Britain and Northern broad bean, alexandrian laurel, date palm, Ireland, hereinafter referred to as Muntingia calabura, feijoa, pawpaw, mammee "United Kingdom"), Austria, apple, longan, litchi, and plants of the genera Netherlands, Cyprus, Greece, Ficus, Phaseolus, Diospyros(excluding those Croatia, Kosovo, Switzerland, listed in appendix 41), Carissa, Juglans, Morus, Spain, Slovenia, Serbia, Germany, Coccoloba, Coffea, Ribes, Vaccinium, Hungary, France, Belgium, Passiflora, Dovyalis, Ziziphus, Spondias, Musa Bosnia and Herzegovina, (excluding immature banana), Carica (excluding Portugal, Former Yugoslav those listed in appendix 1), Psidium, Artocarpus, Republic of Macedonia, Malta, , Annona, Malpighia, Santalum, Garcinia, Vitis Montenegro, Africa, Bermuda, (excluding those listed in appendices 3 and 54), Argentina, Uruguay, Ecuador, El Eugenia, Mangifera (excluding those listed in Salvador, Guatemala, Costa Rica, appendices 2 ,36 ,43 ,51 and 53), Ilex, Colombia, Nicaragua, West Indies Terminalia and Gossypium, and Plants of the (excluding Cuba, Dominican family Sapotaceae, Cucurbitaceae (excluding Republic,Puerto Rico), Panama, those listed in appendices 3 and 42), Cactaceae Paraguay, Brazil, Venezuela, (excluding those listed in appendix 35), Peru, Bolivia, Honduras, Australia Solanaceae (excluding those listed in (excluding Tasmania), Hawaiian appendices 3 and 42), Rosaceae (excluding Islands those listed in appendices 3 and 31) and Rutaceae (excluding those listed in appendices 4 to 8 ,39 ,45 and 56). -

A Survey of Arthropod Biodiversity in the Canopy

A SURVEY OF ARTHROPOD BIODIVERSITY IN THE CANOPIES OF SOUTHERN RED OAK TREES IN THE MARYVILLE COLLEGE WOODS A Report of a Senior Study by Jenna Ann Wade Major: Biology Maryville College Fall, 2005 Date Approved _______________, by _______________ Faculty Supervisor Date Approved _______________, by _______________ Editor ABSTRACT Over the past 75 years, biologists have become increasingly interested in how many and what kinds of organisms live in forest canopies. Numerous studies have shown that large quantities of insects reside in forest canopies, many of which were previously unknown to science. It has also been demonstrated that trees in tropical forests are often stratified in regard to the kinds of organisms found in them, with the canopies having more biological activity than the understories. In this study, the canopies and understories of four Southern Red Oaks located in the Maryville College Woods in Maryville, Tennessee were sampled over a period of eight weeks using a composite flight-interception trap. Two sample trees were located on top of a low ridge. The other two were located on the floodplain of a small creek. A total of 2,142 arthropods were collected from 11 Orders and 65 Families. Shannon’s and Simpson’s diversity indices indicated minimal difference between each sampling site. However, Sorenson’s quantitative index measuring community similarity revealed more distinct differences. The least similar communities were the ridgetop canopies versus the floodplain canopies, which shared 49% of the Families found in them. The most similar communities were all canopies compared to all understories, which shared 67% of the Families found in them. -

Analysing the History of the Derelomine Flower Weevil-Carludovica Association (Coleóptera: Curculionidae; Cyelanthaeeae)

Biological Journal of the Linnean Society, 2004, 81, 483•517. With 17 figures Analysing the history of the derelomine flower weevil-Carludovica association (Coleóptera: Curculionidae; Cyelanthaeeae) NICO M. FRANZ* Escuela de Biología, Universidad de Costa Rica, Ciudad Universitaria 'Rodrigo Fació', Costa Rica Received 14 April 2003; accepted for publication 23 September 2003 The evolutionary history of the interaction among species of derelomine flower weevils (Coleóptera: Curculionidae: Derelomini) and the Panama-hat palm Carludovica (Cyelanthaeeae) is analysed with emphasis on the congruence of (1) topologies and (2) character state transformations in each of the Neotropical clades. For this purpose cladistic analyses are complemented with host plant records, natural history information and selected morphological studies of the associated taxa. The interaction is specialized, involving pollination, oviposition into the inflorescences and the prédation of seeds (particularly within Systenotelus). As results from a range of standard coevolutionary methods of analysis indicate, however, events of colonization, extinction and independent (non-reciprocal) speciation have been abundant throughout the history of the association. At the same time it is possible to specify the homology and suc- cession of characters among species of derelomines and Carludovica and interpret them as reciprocal adaptations to attack and protect the seeds, respectively. It is argued that • in light of the limited evolutionary stability of many insect•plant interactions • the question of coevolution is most effectively addressed by combining information from the character- and topology-based approaches. © 2004 The Linnean Society of London, Biological Journal of the Linnean Society, 2004, 81, 483-517. ADDITIONAL KEYWORDS: cladistics • congruence • coevolution • Derelomini • Ganglionus • Perelleschus • pollination • reciprocal adaptation • seed prédation • Systenotelus.