Doing Your Own Cognate Analyses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Automatic Part-Of-Speech Tagger for Middle Low German

An automatic part-of-speech tagger for Middle Low German Mariya Koleva, Melissa Farasyn, Bart Desmet, Anne Breitbarth and Véronique Hoste Ghent University Syntactically annotated corpora are highly important for enabling large-scale diachronic and diatopic language research. Such corpora have recently been developed for a variety of historical languages, or are still under development. One of those under development is the fully tagged and parsed Corpus of Historical Low German (CHLG), which is aimed at facilitating research into the highly under-researched diachronic syntax of Low German. The present paper reports on a crucial step in creating the corpus, viz. the creation of a part-of-speech tagger for Middle Low German (MLG). Having been transmitted in several non-standardised written varieties, MLG poses a challenge to standard POS taggers, which usually rely on normalized spelling. We outline the major issues faced in the creation of the tagger and present our solutions to them. Keywords: historical linguistics, part-of-speech tagging, conditional random fields, feature selection, normalization 1. Introduction Corpora of historical texts annotated with different levels of grammatical information, such as parts of speech, (inflectional) morphology, syntactic chunks, clausal syntax, provide an important resource for studies of diachronic syntactic variation and change (e.g. Kroch et al. 2000, Rögnvaldsson & Helgadóttir 2011). They enable the automatic extraction of syntactic information from historical texts (more than is manually possible), and allow making statistically valid observations. Apart from reducing the amount of time required for data retrieval, an important advantage is that they make research testable and replicable. The Corpus of Historical Low German (CHLG) (Breitbarth et al. -

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN History of the German Language 1 Indo

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN History of the German Language 1 Indo-European and Germanic Background Indo-European Background It has already been mentioned in this course that German and English are related languages. Two languages can be related to each other in much the same way that two people can be related to each other. If two people share a common ancestor, say their mother or their great-grandfather, then they are genetically related. Similarly, German and English are genetically related because they share a common ancestor, a language which was spoken in what is now northern Germany sometime before the Angles and the Saxons migrated to England. We do not have written records of this language, unfortunately, but we have a good idea of what it must have looked and sounded like. We have arrived at our conclusions as to what it looked and sounded like by comparing the sounds of words and morphemes in earlier written stages of English and German (and Dutch) and in modern-day English and German dialects. As a result of the comparisons we are able to reconstruct what the original language, called a proto-language, must have been like. This particular proto-language is usually referred to as Proto-West Germanic. The method of reconstruction based on comparison is called the comparative method. If faced with two languages the comparative method can tell us one of three things: 1) the two languages are related in that both are descended from a common ancestor, e.g. German and English, 2) the two are related in that one is the ancestor of the other, e.g. -

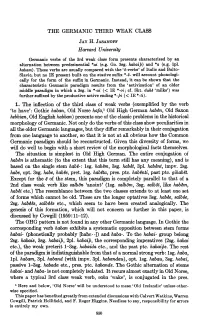

The Germanic Third Weak Class

THE GERMANIC THIRD WEAK CLASS JAY H. JASANOFF Harvard University Germanic verbs of the 3rd weak class form presents characterized by an alternation between predesinential *ai (e.g. Go. 3sg. habai1» and *a (e.g. Ipl. habam). These verbs are usually compared with the 'e-verbs' of Italic and Balto Slavic, but no IE present built on the stative suffix *-e- will account phonologi cally for the form of the suffix in Germanic. Instead, it can be shown that the characteristic Germanic paradigm results from the 'activization' of an older middle paradigm in which a 3sg. in *-ai « IE *-oi; cf. Skt. duh~ 'milks') was further suffixed by the productive active ending *-Pi « IE *-ti). 1. The inflection of the third class of weak verbs (exemplified by the verb 'to have': Gothic haban, Old Norse hafa,! Old High German hab~, Old Saxon hebbian, Old English habban) presents one of the classic problems in the historical morphology of Germanic. Not only do the verbs of this class show peculiarities in all the older Germanic languages, but they differ remarkably in their conjugation from one language to another, so that it is not at all obvious how the Common Germanic paradigm should be reconstructed. Given this diversity of forms, we will do well to begin with a short review of the morphological facts themselves. The situation is simplest in Old High German. The entire conjugation of hab~n is athematic (to the extent that this term still has any meaning), and is based on the single stem hab~-: 1sg. hab~, 3sg. hab~t, 3pl. -

Teaching English-Spanish Cognates Using the Texas 2X2 Picture Book Reading Lists

TEACHING ENGLISH-SPANISH COGNATES USING THE TEXAS 2X2 PICTURE BOOK READING LISTS JOSÉ A. MONTELONGO, ANITA C. HERNÁNDEZ, & ROBERTA J. HERTER ABSTRACT English-Spanish cognates are words that possess identical or nearly identical spellings and meanings in both English and Spanish as a result of being derived mainly from Latin and Greek. Of major importance is the fact that many of the more than 20,000 cognates in English are academic vocabulary words, terms essential for comprehending school texts. The Texas 2x2 Reading List is a list of recommended reading books for children ranging in ages from pre-school to the early primary grades. The list is published yearly by the Children’s Round Table, a division of the Texas Library Association. The books that comprise the Texas 2x2 Reading List are a rich source of vocabulary and contain many English-Spanish cognates. Teachers can use the Texas 2x2 picture books to create a cognate vocabulary lesson that can be taught as a companion to a picture book read- aloud. The purpose of this paper is to present some of the different types of cognate vocabulary lessons that may be created to accompany a picture book read-aloud. The lessons are based on the morphological and spelling regularities between English and Spanish cognates and can be used to teach students how to convert words from one language to another. Examples of the different types of regularities and the Texas 2x2 books that contain them are included, as is an example cognate vocabulary lesson plan to accompany the picture book, Oddrey (Whamond, 2012). -

A Penn-Style Treebank of Middle Low German

A Penn-style Treebank of Middle Low German Hannah Booth Joint work with Anne Breitbarth, Aaron Ecay & Melissa Farasyn Ghent University 12th December, 2019 1 / 47 Context I Diachronic parsed corpora now exist for a range of languages: I English (Taylor et al., 2003; Kroch & Taylor, 2000) I Icelandic (Wallenberg et al., 2011) I French (Martineau et al., 2010) I Portuguese (Galves et al., 2017) I Irish (Lash, 2014) I Have greatly enhanced our understanding of syntactic change: I Quantitative studies of syntactic phenomena over time I Findings which have a strong empirical basis and are (somewhat) reproducible 2 / 47 Context I Corpus of Historical Low German (‘CHLG’) I Anne Breitbarth (Gent) I Sheila Watts (Cambridge) I George Walkden (Konstanz) I Parsed corpus spanning: I Old Low German/Old Saxon (c.800-1050) I Middle Low German (c.1250-1600) I OLG component already available: HeliPaD (Walkden, 2016) I 46,067 words I Heliand text I MLG component currently under development 3 / 47 What is Middle Low German? I MLG = West Germanic scribal dialects in Northern Germany and North-Eastern Netherlands 4 / 47 What is Middle Low German? I The rise and fall of (written) Low German I Pre-800: pre-historical I c.800-1050: Old Low German/Old Saxon I c.1050-1250 Attestation gap (Latin) I c.1250-1370: Early MLG I c.1370-1520: ‘Classical MLG’ (Golden Age) I c.1520-1850: transition to HG as in written domain I c.1850-today: transition to HG in spoken domain 5 / 47 What is Middle Low German? I Hanseatic League: alliance between North German towns and trade outposts abroad to promote economic and diplomatic interests (13th-15th centuries) 6 / 47 What is Middle Low German? I LG served as lingua franca for supraregional communication I High prestige across North Sea and Baltic regions I Associated with trade and economic prosperity I Linguistic legacy I Huge amounts of linguistic borrowings in e.g. -

Old Frisian, an Introduction To

An Introduction to Old Frisian An Introduction to Old Frisian History, Grammar, Reader, Glossary Rolf H. Bremmer, Jr. University of Leiden John Benjamins Publishing Company Amsterdam / Philadelphia TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of 8 American National Standard for Information Sciences — Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Bremmer, Rolf H. (Rolf Hendrik), 1950- An introduction to Old Frisian : history, grammar, reader, glossary / Rolf H. Bremmer, Jr. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. 1. Frisian language--To 1500--Grammar. 2. Frisian language--To 1500--History. 3. Frisian language--To 1550--Texts. I. Title. PF1421.B74 2009 439’.2--dc22 2008045390 isbn 978 90 272 3255 7 (Hb; alk. paper) isbn 978 90 272 3256 4 (Pb; alk. paper) © 2009 – John Benjamins B.V. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, by print, photoprint, microfilm, or any other means, without written permission from the publisher. John Benjamins Publishing Co. · P.O. Box 36224 · 1020 me Amsterdam · The Netherlands John Benjamins North America · P.O. Box 27519 · Philadelphia pa 19118-0519 · usa Table of contents Preface ix chapter i History: The when, where and what of Old Frisian 1 The Frisians. A short history (§§1–8); Texts and manuscripts (§§9–14); Language (§§15–18); The scope of Old Frisian studies (§§19–21) chapter ii Phonology: The sounds of Old Frisian 21 A. Introductory remarks (§§22–27): Spelling and pronunciation (§§22–23); Axioms and method (§§24–25); West Germanic vowel inventory (§26); A common West Germanic sound-change: gemination (§27) B. -

A Middle High German Primer, with Grammar, Notes, and Glossary

> 1053 MIDDLE HIGH GERMAN PRIMER WITH GRAMMAR, NOTES, AND GLOSSARY BY JOSEPH WRIGHT M.A., PH.D., D.C.L., LL.D., L1TT.D. FELLOW OF THE BRITISH ACADEMY CORPUS CHRISTI PROFESSOR OF COMPARATIVE PHILOLOGY IN THE UNIVERSITY OF OXFORD THIRD EDITION RE-WRITTEN AND ENLARGED AT THE CLARENDON PRESS 1917 OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS LONDON EDINBURGH GLASGOW NEW YORK TORONTO MELBOURNE BOMBAY HUMPHREY MILFORD PUBLISHER TO THE UNIVERSITY pr EXTRACTS FROM THE PREFACES TO THE FIRST AND SECOND EDITIONS THE present book has been written in the hope that it will serve as an elementary introduction to the larger German works on the subject from which I have appro- priated whatever seemed necessary for the purpose. In the grammar much aid has been derived from Paul's Mittelhochdeutsche Grammatik, second edition, Halle, 1884, and Weinhold's Mittelhochdeutsche Grammatik, second edition, Paderborn, 1883. The former work, besides con- taining by far the most complete syntax, is also the only Middle High German Grammar which is based on the present state of German Philology. ... I believe that the day is not far distant when English students will take a much more lively interest in the study of their own and the other Germanic languages (especially German and Old Norse) than has hitherto been the case. And if this little book should contribute anything towards furthering the cause, it will have amply fulfilled its purpose. LONDON : January, 1888. WHEN I wrote the preface to the first edition of this primer in 1888, I ventured to predict that the interest of English students in the subject would grow and develop as time went on, but I hardly expected that it would grow so much that a second edition of the book would be required within iv Preface to the Second Edition so short a period. -

Verbs of Letting in Germanic and Romance Languages a Quantitative Investigation Based on a Parallel Corpus of Film Subtitles

Verbs of letting in Germanic and Romance languages A quantitative investigation based on a parallel corpus of film subtitles Natalia Levshina F.R.S.–FNRS, Université catholique de Louvain (Belgium) This study compares eleven verbs of letting in six Germanic and five Romance languages. The aim of this paper is to pinpoint the differences and similarities in the semasiological variation of these verbs, both across and within the two lan- guage groups they represent. The results of a Multidimensional Scaling analysis based on a parallel corpus of film subtitles show that the verbs differ along sev- eral semantic dimensions, such as letting versus leaving, factitive versus permis- sive causation, as well as modality and discourse function. Although the main differences between the verbs lend themselves to a genealogical interpretation (Germanic vs. Romance), a distributional analysis of constructional patterns in which the verbs occur reveals that these differences are in fact distributed areally, with a centre and a periphery. Keywords: letting, parallel corpora, film subtitles, Multidimensional Scaling, Correspondence Analysis, distributional semantics, Romance/Germanic 1. Introduction The aim of this paper is to compare eleven verbs of letting in six Germanic and five Romance languages. The Germanic verbs are the Danishlade , Dutch laten, English let, German lassen, Norwegian la and Swedish låta. The Romance verbs are the French laisser, Italian lasciare, Portuguese deixar, Romanian a lăsa and Spanish dejar. These verbs share the sense of ‘let’, which is illustrated in Example (1): (1) a. EN Let my people go… (King James Version, Exodus 8:1). b. DE Lass mein Volk ziehen… c. -

Introduction to Middle High German: a Reader and Grammar

'W!' 'mAMl^Ali AH^ lEADE ALi«K£P, ^ferif4. -'^ 'V r- I ji ^--^ Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2011 with funding from LYRASIS IVIembers and Sloan Foundation http://www.archive.org/details/introductiontomiOOsenn AN INTRODUCTION TO MIDDLE HIGH GERMAN GATE¥/Ay BOOKS GENERAL EDITORS ERNST FEISE The Johns Hopkins University and The Middlebury College School of German ROBERT O. ROSELER The University of Wisconsin and The Middlebury College School of German AN INTRODUCTION TO MIDDLE HIGH GERMAN A READER AND GRAMMAR By ALFRED SENN The University of Wisconsin New York W. W. NORTON & CO., INC., Publishers Copyright, 1937, by W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. 70 Fifth Ave., New York First Edition PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA PREFACE „ Auf die , Intuition' sollte sich nur bernfen, wer sich die Miihe genommen hat, etwas zic lernen. G. Ehrismann, Geschichte der deiitschen Literatiir bis zum Ausgang des Mittelalters. 2, II, i p. X. THIS publication differs in various points from the tradi- tional Middle High German textbook: i) The whole presentation centers around the texts, and a minimum amount of grammar is given for the interpretation and understanding of the texts. Full understanding of the text will prove essential for literary appreciation and for philological studies. 2) In the introductory part the material is presented in lesson form, making it possible to create study units. The lessons sometimes seem to be rather long. However, many of the given grammatical items are, at least for the beginning, only of secondary importance. If they occur again later, there are footnotes with the necessary references. -

CHAPTER TWENTY History of the German Language 3 Middle High

CHAPTER TWENTY History of the German Language 3 Middle High German As was mentioned in the last chapter, the works of Notker show a very late type of Old High German (OHG) in which many of the vowel distinctions in unstressed syllables evident in earlier OHG were on their way to being levelled out. Notker died in 1023. The beginning of the Middle High German (MHG) period is usually set at about 1050. There are a number of reasons for this, both linguistic and historical. First of all, there were differences in the types of texts and who wrote them. OHG texts were written almost exclusively by members of the clergy, whose business was the Christianisation of Germany. The pagan past with its emphasis on fate, rather than God, as the determiner of all things, was definitely at odds with Christianity and therefore not to be encouraged. As a result we have practically nothing of a pre-Christian nature in OHG. (Fortunately, some of the original Germanic myths were retained in the literature of Medieval Iceland, from which we have gleaned what we know about the Germanic pantheon.) The Holy Roman Empire was established with the coronation of Otto I by the Pope in 962. Over the next two hundred years a number of events of importance in the history of Europe took place. In 1066 there was the Norman conquest of England, which was to change the character of the English language. In 1095 the first of the Crusades, which were to continue over the next two hundred years, began. -

The World's Major Languages

This article was downloaded by: 10.3.98.104 On: 28 Sep 2021 Access details: subscription number Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: 5 Howick Place, London SW1P 1WG, UK The World’s Major Languages Comrie Bernard Germanic Languages Publication details https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/doi/10.4324/9780203301524.ch2 John A. Hawkins Published online on: 28 Nov 2008 How to cite :- John A. Hawkins. 28 Nov 2008, Germanic Languages from: The World’s Major Languages Routledge Accessed on: 28 Sep 2021 https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/doi/10.4324/9780203301524.ch2 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR DOCUMENT Full terms and conditions of use: https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/legal-notices/terms This Document PDF may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproductions, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The publisher shall not be liable for an loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material. 2 Germanic Languages John A. Hawkins The Germanic languages currently spoken fall into two major groups: North Germanic (or Scandinavian) and West Germanic. The former group comprises: Danish, Norwegian (i.e. both the Dano-Norwegian Bokmål and Nynorsk), Swedish, Icelandic, and Faroese. -

Identifying Cognate Sets Across Dictionaries of Related Languages

Identifying Cognate Sets Across Dictionaries of Related Languages by Adam St Arnaud A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Department of Computing Science University of Alberta ⃝c Adam St Arnaud, 2017 Abstract Cognates are words in related languages that have originated from the same word in an ancestor language, such as the English/German word pair father/Vater. Cognate information is critical in the field of historical linguistics, where it is used to deter- mine the relationships between languages and to construct the ancestor languages they originated from. Most recent work in cognate identification focuses on the task of clustering cognates within lists of words each having an identical definition. In that task, only orthographic or phonetic information about a word is utilized when making cognate judgments. We present a system for the more challenging task of identifying cognate sets across dictionaries of related languages. The likelihood of a cognate relationship is calculated on the basis of a rich set of features that capture both phonetic and semantic similarity, as well as the presence of regular sound cor- respondences. The pairwise similarity scores are combined with an average-score clustering algorithm to create sets of words from different languages that may orig- inate from a common proto-word. When tested on the Algonquian language family, our system detects 63% of cognate sets while maintaining cluster purity of 70%. ii iii Acknowledgements First, I would like to thank my supervisor Dr. Grzegorz Kondrak for his mentorship, direction, and support. I learned so much working on our project together and by participating in shared tasks with the NLP team.