ORIGINES ET MUTATIONES Transfer – Exchange – Power

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Program Opieki Nad Zabytkami Gminy Program Opieki Nad Zabytkami

Program Opieki Nad Zabytkami Gminy Stare Pole na lata 20152015----20182018 . Motto: „Nie ulega bowiem w ątpliwo ści, i ż nie tylko rozwój jest istot ą kultury, ale i kultura jest czynnikiem rozwoju ”. Prof. Jacek Purchla We wst ępie do Krajowego Programu Ochrony Zabytków I Opieki Nad Zabytkami na lata 2014-2017 Opracowanie: mgr Dariusz Barton, maj – lipiec 2015 r. 1. WST ĘP. Program Opieki Nad Zabytkami dla Gminy Stare Pole na lata 2015-2018 stanowi kontynuacj ę analogicznego opracowania przyj ętego przez Rad ę Gminy i obowi ązuj ącego w okresie od 2009 do 2013 roku. Zaktualizowany dokument wykorzystuje do świadczenia wynikaj ące z poprzedniego okresu programowania, w tym zarówno osi ągni ęcia w dziedzinie ochrony zabytków i opieki nad zabytkami, jak i zanotowane na tym polu niepowodzenia. Program formułuje w formie tez i postulatów najwa żniejsze działania konieczne do wykonania w perspektywie najbli ższych czterech lat w odniesieniu do dziedzictwa i krajobrazu kulturowego obszaru zawartego w granicach administracyjnych gminy. W swoim ogólnym przesłaniu, okre ślaj ąc wspóln ą platform ę współpracy władz gminy z innymi podmiotami na rzecz ochrony zabytków, odwołuje si ę i opiera na ustaleniach ogłoszonego po raz pierwszy Krajowego Programu Ochrony Zabytków i Opieki Nad Zabytkami na lata 2014-2017 . 2. PODSTAWA PRAWNA OPRACOWANIA GMINNEGO PROGRAMU OPIEKI NAD ZABYTKAMI . Podstaw ą prawn ą dla opracowania gminnego programu opieki nad zabytkami, w tym konkretnym przypadku Programu Opieki Nad Zabytkami Gminy Star Pole na lata 2015-2018, jest ustawa z dnia 23 lipca 2003 r. o ochronie zabytków i opiece nad zabytkami (Dz. U. z 2014 r. -

Väsen I Chronopia Creatures of Chronopia Konstruktör: Johan

Väsen i Chronopia Creatures of Chronopia Konstruktör: Johan Sjöberg Översättning: Redigering: Chronopia: Bill King, Michael Stenmark, Nils Gulliksson, Henrik Strandberg Formgivning: Original: Marcus Thorell Omslag: Adrian Smith Grafisk Form: Illustrationer: Adrian Smith, Alvaro Tapia Koncept: Stefan Ljungqvist, Johan Sjöberg Kartor: Övriga Bidrag: Filip Alexanderson, Hanners Kristoferson, Fredrik Malmberg, Henrik Strandberg, Nils Gulliksson, Sami Sinerva, Jonas Mases, Patric Backlund, Cees Kwadijk Baksida: Paolo Parente Projektledning: Stefan Ljungqvist So you want to learn something about the chronopian people? Forsa the sabranska mysteries, get to know the secrets that made brundusierna so rich, understand marajiputternas brutal fanaticism and unconditional surrender to the black tobacco, nattländarnas desperate escape and ice barbarians worship of Snow Witch. Then I have the book for you my friend. Just look up Melkastors "The chronopian peoples", which delivers the wise man and adventurer all the wisdom you need. If he is still alive? No. When the book arrived, he was executed for blasphemy by the emperor. Read - and maybe you will understand why. Human ethnicities During my many long and intense years as a guest in the brutal, multifaceted and legendary chronopian reality, I had the dubious pleasure to encounter the most varied gallery of the known world has to offer, bump into high and low, exchange experiences with sabranska desert knights, brundusiska trade princes and blue skinned isbarbarer with frosty mustache. I have engaged in telepathy with charibiska hexbarons, given boozed Red Corsairs on the nut, fled howling marajiputtiska fanatics and young and inexperienced taken refuge in faltrakiernas false bosom and sold as a slave to the salt mines. -

Uchwala Nr XXIV.189.2016 Z Dnia 29 Czerwca 2016 R

UCHWAŁA NR XXIV.189.2016 RADY MIEJSKIEJ W SZTUMIE z dnia 29 czerwca 2016 r. w sprawie przyjęcia Gminnego Programu Opieki nad Zabytkami Miasta i Gminy Sztum na lata 2016 - 2020 Na podstawie art. 7 ust.1 pkt 9 ustawy z dnia 8 marca 1990r. o samorządzie gminnym (tekst jednolity Dz. U. z 2016 r. poz. 446) oraz w związku z art. 87 ust. 1, 3 i 4 ustawy z dnia 23 lipca 2003 r. o ochronie zabytków i opiece nad zabytkami (tekst jednolity Dz. U. z 2014 r. poz. 1446 ze zm.) uchwala się, co następuje: § 1. Przyjmuje się Gminny Program Opieki nad Zabytkami Miasta i Gminy Sztum na lata 2016 -2020, stanowiący załącznik nr 1 do niniejszej uchwały. § 2. Wykonanie uchwały powierza się Burmistrzowi Miasta i Gminy Sztum. § 3. Uchwała wchodzi w życie po upływie 14 dni od dnia ogłoszenia w Dzienniku Urzędowym Województwa Pomorskiego. Przewodniczący Rady Miejskiej w Sztumie Czesław Oleksiak Id: 2E8D0EAE-286C-4CC2-B3A1-F081237595B6. Podpisany Strona 1 Załącznik do Uchwały Nr XXIV.189.2016 Rady Miejskiej w Sztumie z dnia 29 czerwca 2016 r. GMINNY PROGRAM OPIEKI NAD ZABYTKAMI MIASTA I GMINY SZTUM NA LATA 2016 – 2020 Opracowanie: mgr inż. arch. Joanna Małuj, doktorantka Politechniki Gdańskiej z zespołem w składzie: mgr inż. arch. Alicja Stefańska, doktorantka Politechniki Gdańskiej mgr inż. arch. Weronika Dettlaff, doktorantka Politechniki Gdańskiej mgr inż. arch. Łukasz Bugalski, doktorant Politechniki Gdańskiej inż. Angelika Plata Angelika Rogożyńska Oliwia Burzyńska Wiktoria Witosławska Maj 2016 Id: 2E8D0EAE-286C-4CC2-B3A1-F081237595B6. Podpisany Strona 1 PROGRAM OPIEKI NAD ZABYTKAMI MIASTA I GMINY SZTUM NA LATA 2016 -2020 1. -

Studium Uwarunkowań I Kierunków Zagospodarowania Przestrzennego

GMINA RYJEWO STUDIUM UWARUNKOWAŃ I KIERUNKÓW ZAGOSPODAROWANIA PRZESTRZENNEGO ZAŁĄCZNIK NR 1, NR 2, NR 3 DO UCHWAŁY NR XLII/295/10 RADY GMINY RYJEWO Z DNIA 27 KWIETNIA 2010R. W SPRAWIE UCHWALENIA STUDIUM UWARUNKOWAŃ I KIERUNKÓW ZAGOSPODAROWANIA PRZESTRZENNEGO GMINY RYJEWO R O K Z A Ł O Ż E N I A 1989 N I P 584-020-36-47 R E G O N 008049023 K R S 0000093085 KAPITAŁ ZAKŁADOWY 84.000 zł Tel/fax (58) 554-84-40 tel. (58) 520-92-22, 520-92-23 Mail: [email protected] www.ppp.gda.pl KWIECIE Ń 2010 R . STUDIUM UWARUNKOWA Ń I KIERUNKÓW ZAGOSPODAROWANIA PRZESTRZENNEGO GMINY RYJEWO PROJEKT STUDIUM UWARUNKOWA Ń I KIERUNKÓW ZAGOSPODAROWANIA PRZESTRZENNEGO GMINY RYJEWO - opracowany na podstawie Uchwały nr XVII/129/2008 Rady Gminy w Ryjewie z dnia 7 lutego 2008 r., w sprawie przyst ąpienia do sporz ądzenia Studium uwarunkowa ń i kierunków zagospodarowania przestrzennego Gminy Ryjewo. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ ZESPÓŁ AUTORSKI Projekt studium wykonany został w latach 2008-2009 we współpracy z Wójtem Gminy Ryjewo oraz Urzędem Gminy w Ryjewie przez zespół autorski Biura Urbanistycznego PPP sp. z o.o. w Gdańsku w następującym składzie: • Główny projektant: mgr inż. arch. Aleksandra Piskorska • Współpraca:……………………………… mgr Daniel Chałupnik • Inżynieria:………………… mgr inż. Michał Ruth, mgr inż. Marta Lisowska • Opracowanie ekofizjograficzne: … …………………… mgr inż. Matylda Piskorska, mgr Katarzyna Marczuk Prognoza oddziaływania na środowisko do projektu zmiany studium została opracowana w 2009 r. przez zespół w składzie: • mgr inż. Matylda Piskorska • mgr Katarzyna Marczuk • mgr inż. arch. Aleksandra Piskorska • mgr inż. Michał Ruth 2 BIURO URBANISTYCZNE PPP SPÓŁKA Z O.O. -

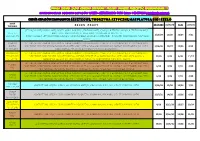

HARMONOGRAM MARZEC CZERWIEC 2021 Dla

UWAGA ZMIANA ZASAD ODBIORU ODPADÓW ! PROSIMY UWAŻNIE PRZECZYTAĆ HARMONOGRAM ! ! ! H A R M O N O G R A M O D B I O R U O D P A D Ó W MARZEC – CZERWIEC 2021 R. PWiK Sztum 0 55 277 22 14, [email protected] ODBIÓR ODPADÓW KOMUNALNYCH: R E S Z T K O W E, T W O R Z Y W A S Z T U C Z N E, M A K U L A T U R A, B I O I S Z K Ł O DZIEŃ KWIECIEŃ CZERWIEC TYGODNIA R E J O N P R A C Y MARZEC MAJ SZTUMSKA WIEŚ, NOWA WIEŚ, BYCZA GÓRA, PAROWY, SZPITALNA WIEŚ, CYGUSY, PIETRZWAŁD PGR, PIETRZWAŁD WIEŚ, PONIEDZ BARLEWICE, BARLEWICZKI, WITOSA, BARCZEWSKIEGO, PIENIĘŻNEGO 1/15/29 12/26 10/24 7/21 MAKULATURA DOMAŃSKIEGO, SZTUMSKA WIEŚ od strony DOMAŃSKIEGO, OSIEDLE NA WZGÓRZU, POLASZKI, MICHOROWO, POSTOLIN, RAMZY WTOREK SZTUMSKA WIEŚ, NOWA WIEŚ, BYCZA GÓRA, PAROWY, SZPITALNA WIEŚ, CYGUSY, PIETRZWAŁD PGR, PIETRZWAŁD WIEŚ, ŚMIECI BARLEWICE, BARLEWICZKI, DOMAŃSKIEGO, SZTUMSKA WIEŚ od strony DOMAŃSKIEGO, OSIEDLE NA WZGÓRZU, POLASZKI, 2/16/30 13/27 11/25 8/22 RESZTKOWE MICHOROWO, POSTOLIN, CZERNIN (TYLKO WIELORODZINNE) CZWARTEK SZTUMSKA WIEŚ, NOWA WIEŚ, BYCZA GÓRA, PAROWY, SZPITALNA WIEŚ, CYGUSY, PIETRZWAŁD PGR, PIETRZWAŁD WIEŚ, TWORZYWA BARLEWICE, BARLEWICZKI, BARCZEWSKIEGO, WITOSA, PIENIĘZNEGO, DOMAŃSKIEGO, SZTUMSKA WIEŚ od strony 11/25 8/22 6/20 4*/17 SZTUCZNE DOMAŃSKIEGO, OSIEDLE NA WZGÓRZU, POLASZKI, MICHOROWO, POSTOLIN, RAMZY SZTUMSKA WIEŚ, NOWA WIEŚ, BYCZA GÓRA, PAROWY, SZPITALNA WIEŚ, CYGUSY, PIETRZWAŁD PGR, PIETRZWAŁD WIEŚ, PIĄTEK BARLEWICE, BARLEWICZKI, DOMAŃSKIEGO, SZTUMSKA WIEŚ od strony DOMAŃSKIEGO, OSIEDLE NA WZGÓRZU, POLASZKI, 5/19 9/23 7/21 4/18 -

Crusading, the Military Orders, and Sacred Landscapes in the Baltic, 13Th – 14Th Centuries ______

TERRA MATRIS: CRUSADING, THE MILITARY ORDERS, AND SACRED LANDSCAPES IN THE BALTIC, 13TH – 14TH CENTURIES ____________________________________ A Thesis Presented to the School of History, Archaeology and Religion Cardiff University ____________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in History & Welsh History (2018) ____________________________________ by Gregory Leighton Abstract Crusading and the military orders have, at their roots, a strong focus on place, namely the Holy Land and the shrines associated with the life of Christ on Earth. Both concepts spread to other frontiers in Europe (notably Spain and the Baltic) in a very quick fashion. Therefore, this thesis investigates the ways that this focus on place and landscape changed over time, when crusading and the military orders emerged in the Baltic region, a land with no Christian holy places. Taking this fact as a point of departure, the following thesis focuses on the crusades to the Baltic Sea Region during the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries. It considers the role of the military orders in the region (primarily the Order of the Teutonic Knights), and how their participation in the conversion-led crusading missions there helped to shape a distinct perception of the Baltic region as a new sacred (i.e. Christian) landscape. Structured around four chapters, the thesis discusses the emergence of a new sacred landscape thematically. Following an overview of the military orders and the role of sacred landscpaes in their ideology, and an overview of the historiographical debates on the Baltic crusades, it addresses the paganism of the landscape in the written sources predating the crusades, in addition to the narrative, legal, and visual evidence of the crusade period (Chapter 1). -

C.193.1935.VII. Conrniunicated to the Council

LEAGUE OF NATIONS C.193.1935.VII. Conrniunicated to the Council. Geneva, May 15th, 193J FRLE CITY 0? DANZIG Situation of -lews in Danzig. The Secretary-General has the honour to communi cate to the Council a letter from the High Commission er of the League of Nations in Danzig, dated May 11th, 1935, transmitting a petition addressed to the League of i étions from the "Verein ,iUdischsr Akademiker1’ and the "Vereinigung selbstHndiger jUdischer Danziger Gewerbetreibender und Handv/erker in der Freien Stadt Danzig ', dated April 9th, 1335, as well as the obser vations of the Senate of May 11th, 1935. Danzig, May 11th, 1935. To the Secretary-General. Sir, I have the honour to enclose herewith a copy of the petition dated April 8 th, 1935, from the "Verein der jUdischer Akademiker" and "Vereinigung selbst&ndiger jUdischer Danziger Gewerbetreibender und Hendwerker in der Freien Stadt Danzig ', as -.veil as the Senate’s answer which I received to-day. In requesting that the matter should be considered by the Council at its approaching meeting I beg to refer to the letter, dated June 10th, 1925, approved by the Council and. subsequently addressed to the High Commissioner, relative to the procedure to be followed regarding petitions which re late to the danger of infringement of the Constitution of Danzig, placed under the guarantee of the League of Nations. I have the honour, etc., (Signed) Sean LESTER, High Commissioner. (Translation furnished by the petitioners). PETITION from "Verein der jUdischen Akademiker" and "Vereinigung selbstëndiger jUdischer Danziger Gewerbetreibender und Handwerker in der Freien Stadt Danzig”. -

Geographischer Index

2 Gerhard-Mercator-Universität Duisburg FB 1 – Jüdische Studien DFG-Projekt "Rabbinat" Prof. Dr. Michael Brocke Carsten Wilke Geographischer und quellenkundlicher Index zur Geschichte der Rabbinate im deutschen Sprachgebiet 1780-1918 mit Beiträgen von Andreas Brämer Duisburg, im Juni 1999 3 Als Dokumente zur äußeren Organisation des Rabbinats besitzen wir aus den meisten deutschen Staaten des 19. Jahrhunderts weder statistische Aufstellungen noch ein zusammenhängendes offizielles Aktenkorpus, wie es für Frankreich etwa in den Archiven des Zentralkonsistoriums vorliegt; die For- schungslage stellt sich als ein fragmentarisches Mosaik von Lokalgeschichten dar. Es braucht nun nicht eigens betont zu werden, daß in Ermangelung einer auch nur ungefähren Vorstellung von Anzahl, geo- graphischer Verteilung und Rechtstatus der Rabbinate das historische Wissen schwerlich über isolierte Detailkenntnisse hinausgelangen kann. Für die im Rahmen des DFG-Projekts durchgeführten Studien erwies es sich deswegen als erforderlich, zur Rabbinatsgeschichte im umfassenden deutschen Kontext einen Index zu erstellen, der möglichst vielfältige Daten zu den folgenden Rubriken erfassen soll: 1. gesetzliche, administrative und organisatorische Rahmenbedingungen der rabbinischen Amts- ausübung in den Einzelstaaten, 2. Anzahl, Sitz und territoriale Zuständigkeit der Rabbinate unter Berücksichtigung der histori- schen Veränderungen, 3. Reihenfolge der jeweiligen Titulare mit Lebens- und Amtsdaten, 4. juristische und historische Sekundärliteratur, 5. erhaltenes Aktenmaterial -

The Archaeology of the Prussian Crusade

Downloaded by [University of Wisconsin - Madison] at 05:00 18 January 2017 THE ARCHAEOLOGY OF THE PRUSSIAN CRUSADE The Archaeology of the Prussian Crusade explores the archaeology and material culture of the Crusade against the Prussian tribes in the thirteenth century, and the subsequent society created by the Teutonic Order that lasted into the six- teenth century. It provides the first synthesis of the material culture of a unique crusading society created in the south-eastern Baltic region over the course of the thirteenth century. It encompasses the full range of archaeological data, from standing buildings through to artefacts and ecofacts, integrated with writ- ten and artistic sources. The work is sub-divided into broadly chronological themes, beginning with a historical outline, exploring the settlements, castles, towns and landscapes of the Teutonic Order’s theocratic state and concluding with the role of the reconstructed and ruined monuments of medieval Prussia in the modern world in the context of modern Polish culture. This is the first work on the archaeology of medieval Prussia in any lan- guage, and is intended as a comprehensive introduction to a period and area of growing interest. This book represents an important contribution to promot- ing international awareness of the cultural heritage of the Baltic region, which has been rapidly increasing over the last few decades. Aleksander Pluskowski is a lecturer in Medieval Archaeology at the University of Reading. Downloaded by [University of Wisconsin - Madison] at 05:00 -

Pro Fi Le Wyso K Ościo We Tras Ro Wero Wy Ch

Duninowo Starkowo Mod³a Lêdowo Golêcino Osiedle Lêdowo Krê¿o³ki 203 ARKUSZ A Duninówko W odnica latarnia morska USTKA 21 Pêplino nad S³upi¹” „Buczyna U Wierzbiêcin S Grabno B Wielichowo S Zapad³e Charnowo Morze Ba³tyckie Ga³êzinowo Przew³oka Zimowiska Orzechowo Bruskowo Wielkie Niestkowo wybrze¿e klifowe Strzelino R 1 0 M¹cznik Strzelinko S z l a k W H a ytowno Bydlino n z e Podd¹bie W³ynkówko a t y W³ynkowo c k i Redwanki Machowino S ³ Machowinko u p i a Niewierowo Dêbina Ba³am¹tek Rowy Swochowo Karzcino Objazda 213 Siemianice Lubuczewo D Radoszkowo o S G¹bino t a c j S i z J. Gardno Jezierzyce G l W Osieki a Bukówko a b k yspa Kamienna e l K S³owiñski ParkNarodowy o R l Kêpno 1 e Dominek 0 j o ( w Lotki t r u y d W n a dla uprawianiasportówwodnych rzeœcie n Komnino a obszar jezioraudostêpniony Retowo w Lêkwica Bukowa i e r z c h n i a ) J. Do³gieMa³e Czysta Wiklino W ysoka Gr¹sino Kukowo Gardna Ma³a J. Do³gieWielkie Rogawica Stojcino P i e Gardna Wielka Z r œ ³ o c Cz³uchy t i e e ñ P G i ¯oruchowo a r y s f Czarny M³yn i t „Rowokó³” k ó w i ¯elkowo Smo³dzino Siecie latarnia morska Smo³dziñski Las Zgojewo Biêcino Choæmirowo Dêbniczka Czo³pino Mrówczyno Wierzchocino Budy ¯elazo Witkowo R R 1 Choæmirowo 1 0 0 ( Drze¿ewo S t r z u l d a n W Œwiêcichowo k a ydma Czo³piñska H n a n z i a k e c y a t w Lipno ie Damnica rz c £okciowe pa³ac h „Ja³owce” n ia ) Przybynin G³odowo Bêdziechowo £ u p a w a Damno Rumsko Wiatrowo Siod³onie Równo Profile wysokościowe tras rowerowych Rodzaj nawierzchni: asfalt, drogi rowerowe o twardej pozosta³e drogi: -

KARTA INFORMACYJNA PRZEDSIĘWZIĘCIA DO WNIOSKU O WYDANIE DECYZJI O ŚRODOWISKOWYCH UWARUNKOWANIACH Zgodnie Z Art

Usługi In żynierskie „In ż-ines” Agnieszka Sawi ńska KARTA INFORMACYJNA PRZEDSIĘWZIĘCIA DO WNIOSKU O WYDANIE DECYZJI O ŚRODOWISKOWYCH UWARUNKOWANIACH zgodnie z art. 3 ust. 1 pkt 5 Ustawy z dnia 3 października 2008 r. o udostępnianiu informacji o środowisku i jego ochronie, udziale społeczeństwa w ochronie środowiska oraz o ocenach oddziaływania na środowisko PRZEBUDOWA DROGI WOJEWÓDZKIEJ NR 522 NA ODCINKU SZTUM GÓRKI – KOŁOZĄB (ODC. O DŁUGOŚCI 5,0 KM) gmina Sztum, powiat sztumski, Lokalizacja: województwo pomorskie Zarząd Dróg Wojewódzkich w Gdańsku Inwestor: ul. Mostowa 11A 80-778 Gdańsk Opracowanie: mgr inż. Agnieszka Sawińska Data opracowania: Październik 2012 SPIS TREŚCI 1. Rodzaj, skala i usytuowanie przedsięwzięcia ................................................................................................................... 3 2. Powierzchnia zajmowanej nieruchomości, a także obiektu budowlanego oraz dotychczasowy sposób ich wykorzystania i pokrycia szatą roślinną ..................................................................................................................................... 9 3. Uwarunkowania przyrodnicze ......................................................................................................................................... 10 3.1. Szata roślinna ....................................................................................................................................................... 10 3.2. Flora epifityczna ................................................................................................................................................... -

Prezentacja Programu Powerpoint

The attractiveness of voivodeships Pomeranian voivodeship Pomeranian Voivodeship Basic information ➢ Capital city – Gdańsk ➢ Area – 18 310,34 km² ➢ Number of cities with county rights - 4 ➢ Number od counties - 16 ➢ Number of municipalities - 25 ➢ Population – 2 315 611 ➢ Working age population - 1 426 312 2 Pomeranian Voivodeship Perspective sectors Information and communication technologies Pharmaceutical and cosmetic industry Biotechnology Logistics Off-shore technologies Energetics 3 Pomeranian Voivodeship The largest companies/ investors in the region Sopot Gdańsk Bytów Starogard Gdański Tczew 4 Pomeranian Voivodeship Special Economic Zones (until 2018) Pomeranian Special Economic Zone Includes 35 subzones located in 5 voivodships. The total area of zonal areas is 2246.2929 ha of which 564.1241 ha are areas in the province Pomeranian, 880.213 ha in the province Kujawsko-Pomorskie, 70.6768 ha in the province Wielkopolskie, 637.2176 ha is located in the Zachodniopomorskie Voivodship, while 94.0614 ha is located in the Lubelskie Voivodship. Słupska Economic Zonef a special economic zone located in the north-western part of Poland, consists of 15 investment subzones in the Pomeranian Voivodship and the West Pomeranian Voivodship. The Pomeranian Agency for Regional Development, based in Słupsk, has been managing the zone since 1997. Słupsk Special Economic Zone covers lands with a total area of 816.7878 ha, located in the following cities: Słupsk, Ustka, Koszalin, Szczecinek and Wałcz and the municipalities: Biesiekierz, Debrzno, Kalisz