Scenic Assessment Handbook State Planning Office Maine Coastal Program

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lidar and Other Evidence for the Southwest Continuation and Late Quaternary Reactivation of the Norumbega Fault System and a Cr

LIDAR and other evidence for the southwest continuation and Late Quaternary reactivation of the Norumbega Fault System and a cross-cutting structure near Biddeford, Maine, USA Ronald T . Marple1 and James D. Hurd, Jr .2 1. 403 Wickersham Avenue, Fort Benning, Georgia 31905, USA 2. Department of Natural Resources and the Environment, The University of Connecticut, 1376 Storrs Road, Storrs, Connecticut 06269-4087, USA Corresponding author <[email protected]> Date received: 14 April 2019 ¶ Date accepted: 01 September 2019 ABSTRACT High-resolution LiDAR (light detection and ranging) images reveal numerous NE-SW-trending geomorphic lineaments that may represent the southwest continuation of the Norumbega fault system (NFS) along a broad, 30- to 50-km-wide zone of brittle faults that continues at least 100 km across southern Maine and southeastern New Hampshire. These lineaments are characterized by linear depressions and valleys, linear drainage patterns, abrupt bends in rivers, and linear scarps. The Nonesuch River, South Portland, and Mackworth faults of the NFS appear to continue up to 100 km southwest of the Saco River along prominent but discontinuous LiDAR lineaments. Southeast-facing scarps that cross drumlins along some of the lineaments in southern Maine suggest that late Quaternary displacements have occurred along these lineaments. Several NW-SE-trending geomorphic features and geophysical lineaments near Biddeford, Maine, may represent a 30-km-long, NW-SE-trending structure that crosses part of the NFS. Brittle NW- SE-trending, pre-Triassic faults in the Kittery Formation at Biddeford Pool, Maine, support this hypothesis. RÉSUMÉ Des images haute résolution prises par LiDAR (détection et télémétrie par ondes lumineuses) dévoilent de nombreux linéaments orientés du NE vers le SO qui pourraient représenter la continuité au sud-ouest du système de failles de Norumbega (SFN) le long d’une vaste zone de 30 à 50 km de largeur de failles cassantes qui se poursuit sur au moins 100 km à travers le sud du Maine et le sud-est du New Hampshire. -

Copyrighted Material

INDEX See also Accommodations and Restaurant indexes, below. GENERAL INDEX best, 9–10 AITO (Association of Blue Hill, 186–187 Independent Tour Brunswick and Bath, Operators), 48 AA (American Automobile A 138–139 Allagash River, 271 Association), 282 Camden, 166–170 Allagash Wilderness AARP, 46 Castine, 179–180 Waterway, 271 Abacus Gallery (Portland), 121 Deer Isle, 181–183 Allen & Walker Antiques Abbe Museum (Acadia Downeast coast, 249–255 (Portland), 122 National Park), 200 Freeport, 132–134 Alternative Market (Bar Abbe Museum (Bar Harbor), Grand Manan Island, Harbor), 220 217–218 280–281 Amaryllis Clothing Co. Acadia Bike & Canoe (Bar green-friendly, 49 (Portland), 122 Harbor), 202 Harpswell Peninsula, Amato’s (Portland), 111 Acadia Drive (St. Andrews), 141–142 American Airlines 275 The Kennebunks, 98–102 Vacations, 50 Acadia Mountain, 203 Kittery and the Yorks, American Automobile Asso- Acadia Mountain Guides, 203 81–82 ciation (AAA), 282 Acadia National Park, 5, 6, Monhegan Island, 153 American Express, 282 192, 194–216 Mount Desert Island, emergency number, 285 avoiding crowds in, 197 230–231 traveler’s checks, 43 biking, 192, 201–202 New Brunswick, 255 American Lighthouse carriage roads, 195 New Harbor, 150–151 Foundation, 25 driving tour, 199–201 Ogunquit, 87–91 American Revolution, 15–16 entry points and fees, 197 Portland, 107–110 America the Beautiful Access getting around, 196–197 Portsmouth (New Hamp- Pass, 45–46 guided tours, 197 shire), 261–263 America the Beautiful Senior hiking, 202–203 Rockland, 159–160 Pass, 46–47 nature -

Winter 2016 Volume 21 No

Fall/Winter 2016 Volume 21 No. 3 A Magazine about Acadia National Park and Surrounding Communities Friends of Acadia Journal Fall/Winter 2016 1 President’s Message FOA AT 30 hen a handful of volunteers And the impact of this work extends at Acadia National Park and beyond Acadia: this fall I attended a Wforward-looking park staff to- conference at the Grand Canyon, where gether founded Friends of Acadia in 1986, I heard how several other friends groups their goal was to provide more opportuni- from around the country are modeling ties for citizens to give back to this beloved their efforts after FOA’s best practices place that gave them so much. Many were and historic successes. Closer to home, avid hikers willing to help with trail up- community members in northern Maine keep. Others were concerned about dwin- have already reached out to FOA for tips dling park funding coming from Washing- as they contemplate a friends group for the ton. Those living in the surrounding towns newly-established Katahdin Woods and shared a desire to help a large federal agen- Waters National Monument. cy better understand and work with our As the brilliant fall colors seemed to small Maine communities. hang on longer than ever at Acadia this These visionaries may or may not year, I enjoyed a late-October morning on have predicted the challenges and the Precipice Trail. The young peregrine opportunities facing Acadia at the dawn FOA falcons had fledged, and the re-opened trail of its second century—such as climate featured a few new rungs and hand-holds change, transportation planning, cruise and partners whom we hope will remain made possible by a generous FOA donor. -

Acadia Activities Brochure

Acadia Mt Desert Island, Maine Samuel E. Lux June 2019 edition planyourvisit/conditions.htm or by searching http://www.mdislander.- Hiking com, the local newspaper, for “precipice trail”. Neither is reliably The hiking in Acadia is, to my mind, up-to-date. The Harbor Walk in Bar the best in America. The approxi- Harbor and the walk along Otter mately 135 miles of trails are beauti- Point (Ocean trail) are both very fully marked and maintained. Many beautiful and very easy. Another have granite steps, or iron ladders or short, easy hike is to Beech Cliffs railings to help negotiate difficult/ from the top of Beech mountain. dangerous spots. They range from road. Only 0.3 mile and great views. flat to straight up. And you get the Kids also love the short walk to the Fig. 1. View of Sand Beach from best views with the least work of any rocky coast and myriad tide pools on part way up Beehive trail trail system anywhere. Beehive to the Wonderland trail. Couch potatoes Gorham mountain and Cadillac can drive to the top of Cadillac Cliffs, then walk back along shore mountain, the highest point in the (Ocean trail), Precipice (appropriately park. Views are worth it. named), and the Jordan Cliffs trail Excellent Circle Hikes followed by a walk back down South Ridge of Penobscot mountain trail are Beehive-Gorham-Ocean Drive my favorites, but there are dozens of Park at Sand Beach on the Park Loop great ones, at least 50 overall. For Road. Do this hike early in the day kids over 6 to 7 years the Beehive trail before the crowds arrive. -

Watchful Me. the Great State of Maine Lighthouses Maine Department of Economic Development

Maine State Library Digital Maine Economic and Community Development Economic and Community Development Documents 1-2-1970 Watchful Me. The Great State of Maine Lighthouses Maine Department of Economic Development Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalmaine.com/decd_docs Recommended Citation Maine Department of Economic Development, "Watchful Me. The Great State of Maine Lighthouses" (1970). Economic and Community Development Documents. 55. https://digitalmaine.com/decd_docs/55 This Text is brought to you for free and open access by the Economic and Community Development at Digital Maine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Economic and Community Development Documents by an authorized administrator of Digital Maine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. {conti11u( d lrom other sidt') DELIGHT IN ME . ... » d.~ 3~ ; ~~ HALF-WAY ROCK (1871], 76' \\:white granite towrr: dwPll ing. Submerged ledge halfway between Cape Small Point BUT DON'T DE-LIGHT ME. and Capp Elizabeth: Casco Bay. Those days are gone -- thP era of sail -- when our harbors d, · LITTLE MARK ISLAND MONUMENT (1927), 74' W: black and bays \\'ere filled with merchant and fishing ships powered atchful and white square pyramid. On bare islet. off S. Harpswell: by the wind. If our imagination sings to us that those vvere Casco Bay. days o! daring and adventure such reverie is not mistaken . PORTLAND LIGHTSHIP (1903], 65' W: red hull, "PORT Tho thP sailing ships arP few now, still with us are the LAND" on sides: circular gratings at mastheads. Off lighthousPs, shining into thP past e\'f~n while lighting the \vay Portland Harbor. for today's navigators aboard modern ships. -

NHL MEDIA DIRECTORY 2012-13 TABLE of CONTENTS Page Page NHL DIRECTORY NHL MEDIA NHL Offices

NHL MEDIA DIRECTORY 2012-13 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE PAGE NHL DIRECTORY NHL MEDIA NHL Offices ...........................................3 NHL.com ...............................................9 NHL Executive .......................................4 NHL Network .......................................10 NHL Communications ............................4 NHL Studios ........................................11 NHL Green ............................................6 NHL MEDIA RESOURCES .................. 12 NHL MEMBER CLUBS Anaheim Ducks ...................................19 HOCKEY ORGANIZATIONS Boston Bruins ......................................25 Hockey Canada .................................248 Buffalo Sabres .....................................32 Hockey Hall of Fame .........................249 Calgary Flames ...................................39 NHL Alumni Association ........................7 Carolina Hurricanes .............................45 NHL Broadcasters’ Association .........252 Chicago Blackhawks ...........................51 NHL Players’ Association ....................16 Colorado Avalanche ............................56 Professional Hockey Writers’ Columbus Blue Jackets .......................64 Association ...................................251 Dallas Stars .........................................70 U.S. Hockey Hall of Fame Museum ..249 Detroit Red Wings ...............................76 USA Hockey Inc. ...............................250 Edmonton Oilers ..................................83 NHL STATISTICAL CONSULTANT Florida -

Mt. Agamenticus Public Access and Trail Plan

2012 Mt. Agamenticus Public Access and Trail Plan Prepared by the Southern Maine Regional Planning Commission For the Mount Agamenticus Steering Committee Financial assistance provided by the New Hampshire Charitable Foundation TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction........................................................................................................ 3 Purpose and Scope of Plan..............................................................................................3 Cooperative Management ...............................................................................................3 I. General Overview.......................................................................................... 3 Ownership .......................................................................................................................4 Acquisition History.........................................................................................................4 Trail Management Area ..................................................................................................5 Previous Studies..............................................................................................................5 II. Regional Significance, Natural, Cultural and Scenic Resources ............. 7 General ............................................................................................................................7 III. Public Use, Access and Recreational Resources...................................... 8 Past and Current Uses .....................................................................................................8 -

Natural Resource Inventory

Natural Resource Inventory Conservation Lands, Sears Island Searsport, Maine For: Friends of Sears Island c/o Marietta Ramsdell PO Box 222, Searsport 04974 Ph. 207 548-0142 [email protected] By: Alison C. Dibble, Ph.D. Jake Maier Stewards LLC JM Forestry P.O. Box 321 6 Lower Falls Road Brooklin, ME 04616 Orland, ME 04472 Ph. 207 359-4659 [email protected] Ph. 207 469-0231 [email protected] http://jmforestry.com 18 January 2011 SUMMARY During the growing season in 2010, Stewards LLC and JM Forestry conducted at Sears Island a natural resource inventory of the new 601-ac conservation easement, held by Maine Coast Heritage Trust. This is located in the lower Penobscot River in Searsport, Waldo County, Maine. As of the 1970s, several large industrial development schemes were proposed for Sears Island. Since the 1990s the island has belonged to the state of Maine. A paved causeway constructed in the 1980s provides year-round access to a gate at the north end of the island. In January 2009 the Friends of Sears Island (FOSI), a nonprofit organization, assumed responsibility for stewardship of the conservation area and this inventory is part of the management planning process. A 70- acre portion of the conservation area includes a vernal pool and a potential building site intended for a future education/ visitor center. The remaining acreage is former farm fields, mature and successional forest, wet forest, streams, and tidal shore. An archaeological site at the north end of the island was documented with an extensive report in 1983. Historic land uses included agriculture and seasonal residences, but no structures remain. -

Nine Mile Thru Trail by Tom Sidar Long Cove to Schoodic Beach Long Pond Stream Runs North from the Outlet of Long Pond in the Town of Sullivan

Protecting the Land You Love NO. 58 SPRING 2013 Nine Mile Thru Trail by Tom Sidar Long Cove to Schoodic Beach Long Pond Stream runs north from the outlet of Long Pond in the town of Sullivan. Bounded by steep, hard granite ledges on the east, clear water runs in sparkling riffles and drops over miniature falls forming small pools and eddies that flow over fallen leaves and broken birch. Fur- ther along, the water slows and runs through dream-like, mossy banks of cedar swamp with deer tracks im- printed along the stream bank. December 30, 2011. Phillip Dunbar and I are walking north on Long Pond Brook. This is Dunbar land, hun- BROOKS dreds of acres of it, passed through ROB the generations. Phillip knows this land well. He tells me that, as a boy, PHOTO he would hunt and fish these waters and woods until daylight faded. This aerial photo shows the whole landscape of Long Pond to Schoodic and north. I am here for Frenchman Bay Conservancy. We are interested in The vision of this thru trail that once seemed purchasing a portion of this land as a link in a hiking trail that would be dreamy is starting to come into focus. open to the public from Old Route Over the past eight years, thanks and I am left to my own meandering One at Long Cove in Sullivan all the to the generosity of Land For Maine’s thoughts. “There are miles and miles way to the State of Maine Reserve Future, our members and friends, of habitat for wildlife like partridge, Land on the summit of Schoodic FBC has acquired the Schoodic Bog deer, snowshoe hare, brook trout, Mountain. -

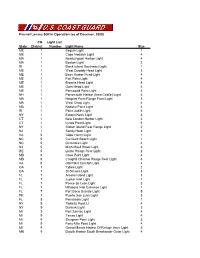

Fresnel Lenses Still in Operation (As of Decemer, 2008) State CG District

Fresnel Lenses Still in Operation (as of Decemer, 2008) CG Light List State District Number Light Name Size ME 1 Seguin Light 1 ME 1 Cape Neddick Light 4 MA 1 Newburyport Harbor Light 4 MA 1 Boston Light 2 RI 1 Block Island Southeast Light 1 ME 1 West Quoddy Head Light 3 ME 1 Bass Harbor Head Light 4 ME 1 Fort Point Light 4 ME 1 Browns Head Light 4 ME 1 Owls Head Light 4 ME 1 Pemaquid Point Light 4 NH 1 Portsmouth Harbor (New Castle) Light 4 MA 1 Hospital Point Range Front Light 3 MA 1 West Chop Light 4 MA 1 Nobska Point Light 4 RI 1 Point Judith Light 4 NY 1 Eatons Neck Light 3 CT 1 New London Harbor Light 4 CT 1 Lynde Point Light 5 NY 1 Staten Island Rear Range Light 2 NJ 1 Sandy Hook Light 3 VA 5 Cape Henry Light 1 NC 5 Currituck Beach Light 1 NC 5 Ocracoke Light 4 NJ 5 Miah Maull Shoal Light 4 DE 5 Liston Range Rear Light 2 MD 5 Cove Point Light 4 MD 5 Craighill Channel Range Rear Light 4 VA 5 Old Point Comfort Light 4 GA 7 Tybee Light 2 GA 7 St Simons Light 3 FL 7 Amelia Island Light 3 FL 7 Jupiter Inlet Light 1 FL 7 Ponce de Leon Light 3 FL 7 Hillsboro Inlet Entrance Light 1 FL 7 Port Boca Grande Light 5 PR 7 Puerto San Juan Light 3 FL 8 Pensacola Light 1 NY 9 Tibbetts Point Lt 4 NY 9 Dunkirk Light 3 MI 9 Port Sanilac Light 4 MI 9 Tawas Light 4 MI 9 Sturgeon Point Light 3 MI 9 Forty-Mile Point Light 4 MI 9 Grand Marais Harbor Of Refuge Inner Light 5 MN 9 Duluth Harbor South Breakwater Outer Light 4 CG Light List State District Number Light Name Size MN 9 Duluth Harbor North Pier Light 5 MN 9 Grand Marais Light 5 MI 9 St James Light -

A History of Oysters in Maine (1600S-1970S) Randy Lackovic University of Maine, [email protected]

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Darling Marine Center Historical Documents Darling Marine Center Historical Collections 3-2019 A History of Oysters in Maine (1600s-1970s) Randy Lackovic University of Maine, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/dmc_documents Part of the Aquaculture and Fisheries Commons, History of Science, Technology, and Medicine Commons, and the United States History Commons Repository Citation Lackovic, Randy, "A History of Oysters in Maine (1600s-1970s)" (2019). Darling Marine Center Historical Documents. 22. https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/dmc_documents/22 This Newsletter is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Darling Marine Center Historical Documents by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A History of Oysters in Maine (1600s-1970s) This is a history of oyster abundance in Maine, and the subsequent decline of oyster abundance. It is a history of oystering, oyster fisheries, and oyster commerce in Maine. It is a history of the transplanting of oysters to Maine, and experiments with oysters in Maine, and of oyster culture in Maine. This history takes place from the 1600s to the 1970s. 17th Century {}{}{}{} In early days, oysters were to be found in lavish abundance along all the Atlantic coast, though Ingersoll says it was at least a small number of oysters on the Gulf of Maine coast.86, 87 Champlain wrote that in 1604, "All the harbors, bays, and coasts from Chouacoet (Saco) are filled with every variety of fish. -

Gatewaytomaine.Org (207) 363-4422 AUTHENTIC YEAR-ROUND EXPERIENCES

2021-2022 The Official Business Resource Guide for Residents & Visitors gatewaytomaine.org (207) 363-4422 AUTHENTIC YEAR-ROUND EXPERIENCES. AUTHENTICALLY MAINE. Located just an hour north of Boston, and 45 minutes south of Portland, surround yourself with incomparable accommodations, locally-inspired cuisine and passionate service. Enjoy a broad array of activities including our Northpoint Driving Range, Igloos at Nubb’s Lobster Shack, snuggling by the fireplace or elemental-inspired spa services to further enrich your escape. Discover a new generation of Cliff House and build memories that will last a lifetime, all cloaked in the comfort and warmth of attentive service. 207 361 1000 | www.cliffhousemaine.com | 591 Shore Road, Cape Neddick, ME 03902 2 York Region Chamber of Commerce shouldshould bebe VACATIONVACATIONyouryour thisthis goodgood Heated Indoor & Outdoor Pools ~ Jacuzzis ~ Fitness Centers Free Wi-Fi & Computer Use ~ On Demand & Premium Movie Programming Raspberri’s for the Area’s Best Breakfast ~ Refrigerators, Coffee Makers Walk to Beaches ~ Outlet Shopping in Kittery & Freeport Seasonal Trolley to Beaches and Village 449 Main Street 336 Main Street 687 Main Street P. O . Box 2240 P. O . Box 2190 P. O . Box 2010 Ogunquit, ME 03907 Ogunquit, ME 03907 Ogunquit, ME 03907 800.646.5001 800.646.4544 800.646.6453 Seasonal Playhouse, Spa, Golf & Dinner Packages 173431_CofC_2017.indd 1 9/13/16 1:59 PM AREA INFO YORK REGION CHAMBER OF COMMERCE 2020 OFFICERS & BOARD OF DIRECTORS Matthew Howell Harry Norton, Jr. Troy Williams Rich Goodenough Caitlynn Ramsey Board Chair Vice Chair Treasurer Immediate Past Chair Secretary Clark & Howell Norton’s Carpentry and Williams Realty Partners Kennebunk Savings Bank Anchorage Inn Attorneys At Law Architectural Salvage, Inc.