Natural Resources Chapter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

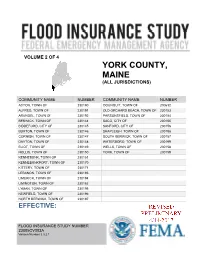

Preliminary Flood Insurance Study

VOLUME 4 OF 4 YORK COUNTY, MAINE (ALL JURISDICTIONS) COMMUNITY NAME NUMBER COMMUNITY NAME NUMBER ACTON, TOWN OF 230190 OGUNQUIT, TOWN OF 230632 ALFRED, TOWN OF 230191 OLD ORCHARD BEACH, TOWN OF 230153 ARUNDEL, TOWN Of 230192 PARSONSFIELD, TOWN OF 230154 BERWICK, TOWN OF 230144 SACO, CITY OF 230155 BIDDEFORD, CITY OF 230145 SANFORD, CITY OF 230156 BUXTON, TOWN OF 230146 SHAPLEIGH, TOWN OF 230198 CORNISH, TOWN OF 230147 SOUTH BERWICK, TOWN OF 230157 DAYTON, TOWN OF 230148 WATERBORO, TOWN OF 230199 ELIOT, TOWN OF 230149 WELLS, TOWN OF 230158 HOLLIS, TOWN OF 230150 YORK, TOWN OF 230159 KENNEBUNK, TOWN OF 230151 KENNEBUNKPORT, TOWN OF 230170 KITTERY, TOWN OF 230171 LEBANON, TOWN OF 230193 LIMERICK, TOWN OF 230194 LIMINGTON, TOWN OF 230152 LYMAN, TOWN OF 230195 NEWFIELD, TOWN OF 230196 NORTH BERWICK, TOWN OF 230197 EFFECTIVE: FLOOD INSURANCE STUDY NUMBER 23005CV004A Version Number 2.3.2.1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Volume 1 Page SECTION 1.0 – INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 The National Flood Insurance Program 1 1.2 Purpose of this Flood Insurance Study Report 2 1.3 Jurisdictions Included in the Flood Insurance Study Project 2 1.4 Considerations for using this Flood Insurance Study Report 20 SECTION 2.0 – FLOODPLAIN MANAGEMENT APPLICATIONS 31 2.1 Floodplain Boundaries 31 2.2 Floodways 43 2.3 Base Flood Elevations 44 2.4 Non-Encroachment Zones 44 2.5 Coastal Flood Hazard Areas 45 2.5.1 Water Elevations and the Effects of Waves 45 2.5.2 Floodplain Boundaries and BFEs for Coastal Areas 46 2.5.3 Coastal High Hazard Areas 47 2.5.4 Limit of Moderate Wave Action 48 SECTION -

Lidar and Other Evidence for the Southwest Continuation and Late Quaternary Reactivation of the Norumbega Fault System and a Cr

LIDAR and other evidence for the southwest continuation and Late Quaternary reactivation of the Norumbega Fault System and a cross-cutting structure near Biddeford, Maine, USA Ronald T . Marple1 and James D. Hurd, Jr .2 1. 403 Wickersham Avenue, Fort Benning, Georgia 31905, USA 2. Department of Natural Resources and the Environment, The University of Connecticut, 1376 Storrs Road, Storrs, Connecticut 06269-4087, USA Corresponding author <[email protected]> Date received: 14 April 2019 ¶ Date accepted: 01 September 2019 ABSTRACT High-resolution LiDAR (light detection and ranging) images reveal numerous NE-SW-trending geomorphic lineaments that may represent the southwest continuation of the Norumbega fault system (NFS) along a broad, 30- to 50-km-wide zone of brittle faults that continues at least 100 km across southern Maine and southeastern New Hampshire. These lineaments are characterized by linear depressions and valleys, linear drainage patterns, abrupt bends in rivers, and linear scarps. The Nonesuch River, South Portland, and Mackworth faults of the NFS appear to continue up to 100 km southwest of the Saco River along prominent but discontinuous LiDAR lineaments. Southeast-facing scarps that cross drumlins along some of the lineaments in southern Maine suggest that late Quaternary displacements have occurred along these lineaments. Several NW-SE-trending geomorphic features and geophysical lineaments near Biddeford, Maine, may represent a 30-km-long, NW-SE-trending structure that crosses part of the NFS. Brittle NW- SE-trending, pre-Triassic faults in the Kittery Formation at Biddeford Pool, Maine, support this hypothesis. RÉSUMÉ Des images haute résolution prises par LiDAR (détection et télémétrie par ondes lumineuses) dévoilent de nombreux linéaments orientés du NE vers le SO qui pourraient représenter la continuité au sud-ouest du système de failles de Norumbega (SFN) le long d’une vaste zone de 30 à 50 km de largeur de failles cassantes qui se poursuit sur au moins 100 km à travers le sud du Maine et le sud-est du New Hampshire. -

MASSACHUSETTS: Or the First Planters of New-England, the End and Manner of Their Coming Thither, and Abode There: in Several EPISTLES (1696)

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Joshua Scottow Papers Libraries at University of Nebraska-Lincoln 1696 MASSACHUSETTS: or The first Planters of New-England, The End and Manner of their coming thither, and Abode there: In several EPISTLES (1696) John Winthrop Governor, Massachusetts Bay Colony Thomas Dudley Deputy Governor, Massachusetts Bay Colony John Allin Minister, Dedham, Massachusetts Thomas Shepard Minister, Cambridge, Massachusetts John Cotton Teaching Elder, Church of Boston, Massachusetts See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/scottow Part of the American Studies Commons Winthrop, John; Dudley, Thomas; Allin, John; Shepard, Thomas; Cotton, John; Scottow, Joshua; and Royster,, Paul Editor of the Online Electronic Edition, "MASSACHUSETTS: or The first Planters of New- England, The End and Manner of their coming thither, and Abode there: In several EPISTLES (1696)" (1696). Joshua Scottow Papers. 7. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/scottow/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Libraries at University of Nebraska-Lincoln at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Joshua Scottow Papers by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Authors John Winthrop; Thomas Dudley; John Allin; Thomas Shepard; John Cotton; Joshua Scottow; and Paul Royster, Editor of the Online Electronic Edition This article is available at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/ scottow/7 ABSTRACT CONTENTS In 1696 there appeared in Boston an anonymous 16mo volume of 56 pages containing four “epistles,” written from 66 to 50 years earlier, illustrating the early history of the colony of Massachusetts Bay. -

Mt. Agamenticus Public Access and Trail Plan

2012 Mt. Agamenticus Public Access and Trail Plan Prepared by the Southern Maine Regional Planning Commission For the Mount Agamenticus Steering Committee Financial assistance provided by the New Hampshire Charitable Foundation TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction........................................................................................................ 3 Purpose and Scope of Plan..............................................................................................3 Cooperative Management ...............................................................................................3 I. General Overview.......................................................................................... 3 Ownership .......................................................................................................................4 Acquisition History.........................................................................................................4 Trail Management Area ..................................................................................................5 Previous Studies..............................................................................................................5 II. Regional Significance, Natural, Cultural and Scenic Resources ............. 7 General ............................................................................................................................7 III. Public Use, Access and Recreational Resources...................................... 8 Past and Current Uses .....................................................................................................8 -

Gatewaytomaine.Org (207) 363-4422 AUTHENTIC YEAR-ROUND EXPERIENCES

2021-2022 The Official Business Resource Guide for Residents & Visitors gatewaytomaine.org (207) 363-4422 AUTHENTIC YEAR-ROUND EXPERIENCES. AUTHENTICALLY MAINE. Located just an hour north of Boston, and 45 minutes south of Portland, surround yourself with incomparable accommodations, locally-inspired cuisine and passionate service. Enjoy a broad array of activities including our Northpoint Driving Range, Igloos at Nubb’s Lobster Shack, snuggling by the fireplace or elemental-inspired spa services to further enrich your escape. Discover a new generation of Cliff House and build memories that will last a lifetime, all cloaked in the comfort and warmth of attentive service. 207 361 1000 | www.cliffhousemaine.com | 591 Shore Road, Cape Neddick, ME 03902 2 York Region Chamber of Commerce shouldshould bebe VACATIONVACATIONyouryour thisthis goodgood Heated Indoor & Outdoor Pools ~ Jacuzzis ~ Fitness Centers Free Wi-Fi & Computer Use ~ On Demand & Premium Movie Programming Raspberri’s for the Area’s Best Breakfast ~ Refrigerators, Coffee Makers Walk to Beaches ~ Outlet Shopping in Kittery & Freeport Seasonal Trolley to Beaches and Village 449 Main Street 336 Main Street 687 Main Street P. O . Box 2240 P. O . Box 2190 P. O . Box 2010 Ogunquit, ME 03907 Ogunquit, ME 03907 Ogunquit, ME 03907 800.646.5001 800.646.4544 800.646.6453 Seasonal Playhouse, Spa, Golf & Dinner Packages 173431_CofC_2017.indd 1 9/13/16 1:59 PM AREA INFO YORK REGION CHAMBER OF COMMERCE 2020 OFFICERS & BOARD OF DIRECTORS Matthew Howell Harry Norton, Jr. Troy Williams Rich Goodenough Caitlynn Ramsey Board Chair Vice Chair Treasurer Immediate Past Chair Secretary Clark & Howell Norton’s Carpentry and Williams Realty Partners Kennebunk Savings Bank Anchorage Inn Attorneys At Law Architectural Salvage, Inc. -

The Beginning of Winchester on Massachusett Land

Posted at www.winchester.us/480/Winchester-History-Online THE BEGINNING OF WINCHESTER ON MASSACHUSETT LAND By Ellen Knight1 ENGLISH SETTLEMENT BEGINS The land on which the town of Winchester was built was once SECTIONS populated by members of the Massachusett tribe. The first Europeans to interact with the indigenous people in the New Settlement Begins England area were some traders, trappers, fishermen, and Terminology explorers. But once the English merchant companies decided to The Sachem Nanepashemet establish permanent settlements in the early 17th century, Sagamore John - English Puritans who believed the land belonged to their king Wonohaquaham and held a charter from that king empowering them to colonize The Squaw Sachem began arriving to establish the Massachusetts Bay Colony. Local Tradition Sagamore George - For a short time, natives and colonists shared the land. The two Wenepoykin peoples were allies, perhaps uneasy and suspicious, but they Visits to Winchester were people who learned from and helped each other. There Memorials & Relics were kindnesses on both sides, but there were also animosities and acts of violence. Ultimately, since the English leaders wanted to take over the land, co- existence failed. Many sachems (the native leaders), including the chief of what became Winchester, deeded land to the Europeans and their people were forced to leave. Whether they understood the impact of their deeds or not, it is to the sachems of the Massachusetts Bay that Winchester owes its beginning as a colonized community and subsequent town. What follows is a review of written documentation KEY EVENTS IN EARLY pertinent to the cultural interaction and the land ENGLISH COLONIZATION transfers as they pertain to Winchester, with a particular focus on the native leaders, the sachems, and how they 1620 Pilgrims land at Plymouth have been remembered in local history. -

FIS Report Template May 2016 Draft

VOLUME 2 OF 4 YORK COUNTY, MAINE (ALL JURISDICTIONS) COMMUNITY NAME NUMBER COMMUNITY NAME NUMBER ACTON, TOWN OF 230190 OGUNQUIT, TOWN OF 230632 ALFRED, TOWN OF 230191 OLD ORCHARD BEACH, TOWN OF 230153 ARUNDEL, TOWN Of 230192 PARSONSFIELD, TOWN OF 230154 BERWICK, TOWN OF 230144 SACO, CITY OF 230155 BIDDEFORD, CITY OF 230145 SANFORD, CITY OF 230156 BUXTON, TOWN OF 230146 SHAPLEIGH, TOWN OF 230198 CORNISH, TOWN OF 230147 SOUTH BERWICK, TOWN OF 230157 DAYTON, TOWN OF 230148 WATERBORO, TOWN OF 230199 ELIOT, TOWN OF 230149 WELLS, TOWN OF 230158 HOLLIS, TOWN OF 230150 YORK, TOWN OF 230159 KENNEBUNK, TOWN OF 230151 KENNEBUNKPORT, TOWN OF 230170 KITTERY, TOWN OF 230171 LEBANON, TOWN OF 230193 LIMERICK, TOWN OF 230194 LIMINGTON, TOWN OF 230152 LYMAN, TOWN OF 230195 NEWFIELD, TOWN OF 230196 NORTH BERWICK, TOWN OF 230197 EFFECTIVE: FLOOD INSURANCE STUDY NUMBER 23005CV002A Version Number 2.3.2.1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Volume 1 Page SECTION 1.0 – INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 The National Flood Insurance Program 1 1.2 Purpose of this Flood Insurance Study Report 2 1.3 Jurisdictions Included in the Flood Insurance Study Project 2 1.4 Considerations for using this Flood Insurance Study Report 20 SECTION 2.0 – FLOODPLAIN MANAGEMENT APPLICATIONS 31 2.1 Floodplain Boundaries 31 2.2 Floodways 43 2.3 Base Flood Elevations 44 2.4 Non-Encroachment Zones 44 2.5 Coastal Flood Hazard Areas 45 2.5.1 Water Elevations and the Effects of Waves 45 2.5.2 Floodplain Boundaries and BFEs for Coastal Areas 46 2.5.3 Coastal High Hazard Areas 47 2.5.4 Limit of Moderate Wave Action 48 SECTION -

YDPHC Physical Activity Guide 1.2019

──── Acton Alfred Arundel Berwick Biddeford Buxton Cornish Dayton Eliot Hollis Kennebunk Kennebunkport Kittery Lebanon Limerick Limington Lyman YORK COUNTY Newfield North Berwick PHYSICAL ACTIVITY Ogunquit Old Orchard Beach RESOURCE GUIDE Parsonsfield Saco Sanford Brought to you by: Shapleigh South Berwick Waterboro Wells York ──── The York District Public Health Council (YDPHC) is excited to present a Physical Activity Resource guide that includes all 29 communities of York County. This guide has been updated from the former York County Physical Activity Resource Guide from 2015. YDPHC is a representative, district-wide body formed in partnership with the Maine Center for Disease Control and Prevention (MeCDC) to engage in collaborative planning and decision-making for the delivery of the Ten Essential Public Health Services in the York Public Health District. The York Public Health District includes all communities in York County. Our mission is to promote, improve, sustain, and advocate for the delivery of the essential public health services in York County. We recognize that this guide does not represent ALL the activities available to residents of York County. We aim to highlight free and public resources available to all. Many other options are available for your wellness needs. We encourage you to let us know if there is something that we missed. Our hope is that this resource guide will be useful to you and encourage physical activity among all members of your family. Use this guide only as intended - as a guide. As with any physical activity, there may be risks associated. Work within your own limits. It is your responsibility to determine if a new activity is right for you and your family. -

This Week in New Brunswick History

This Week in New Brunswick History In Fredericton, Lieutenant-Governor Sir Howard Douglas officially opens Kings January 1, 1829 College (University of New Brunswick), and the Old Arts building (Sir Howard Douglas Hall) – Canada’s oldest university building. The first Baptist seminary in New Brunswick is opened on York Street in January 1, 1836 Fredericton, with the Rev. Frederick W. Miles appointed Principal. Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) becomes responsible for all lines formerly January 1, 1912 operated by the Dominion Atlantic Railway (DAR) - according to a 999 year lease arrangement. January 1, 1952 The town of Dieppe is incorporated. January 1, 1958 The city of Campbellton and town of Shippagan become incorporated January 1, 1966 The city of Bathurst and town of Tracadie become incorporated. Louis B. Mayer, one of the founders of MGM Studios (Hollywood, California), January 2, 1904 leaves his family home in Saint John, destined for Boston (Massachusetts). New Brunswick is officially divided into eight counties of Saint John, Westmorland, Charlotte, Northumberland, King’s, Queen’s, York and Sunbury. January 3, 1786 Within each county a Shire Town is designated, and civil parishes are also established. The first meeting of the New Brunswick Legislature is held at the Mallard House January 3, 1786 on King Street in Saint John. The historic opening marks the official business of developing the new province of New Brunswick. Lévite Thériault is elected to the House of Assembly representing Victoria January 3, 1868 County. In 1871 he is appointed a Minister without Portfolio in the administration of the Honourable George L. Hatheway. -

Scenic Assessment Handbook State Planning Office Maine Coastal Program

Scenic Assessment Handbook State Planning Office Maine Coastal Program i Scenic Assessment Handbook State Planning Office Maine Coastal Program Prepared for the State Planning Office by Terry DeWan Terrence J. DeWan & Associates Landscape Architects Yarmouth, Maine October 2008 Printed Under Appropriation # 013-07B-3850-008201-8001 i Credits Prinicpal Author: Terry DeWan, Terrence J. Permission to use historic USGS maps from DeWan & Associates, Yarmouth, Maine University of New Hampshire Library web . with assistance from Dr. James Palmer, Es- site from Maptech, Inc. sex Junction, Vermont and Judy Colby- George, Spatial Alternatives, Yarmouth, This project was supported with funding Maine. from the Maine Coast Protection Initiative’s Implementation Grants program. The A project of the Maine State Planning Of- Maine Coast Protection Initiative is a first- fice, Jim Connors, Coordinator. of-its kind public-private partnership de- signed to increase the pace and quality of Special Thanks to the Maine Coastal Pro- land protection by enhancing the capacity gram Initiative (MCPI) workgroup: of Maine’s conservation community to pre- serve the unique character of the Maine • Judy Gates, Maine Department of coast. This collaborative effort is led by the Transportation Land Trust Alliance, NOAA Coastal Serv- • Bob LaRoche, Maine Department of ices Center, Maine Coast Heritage Trust, the Transportation Maine State Planning Office, and a coalition • Deb Chapman, Georges River Land of supporting organizations in Maine. Trust • Phil Carey, Land Use Team, Maine Printed Under Appropriation # 013-07B- State Planning Office 3850-008201-8001 • Stephen Claesson, University of New Hampshire • Jim Connors, Maine State Planning Office (Chair) • Amy Winston, Lincoln County Eco- nomic Development Office • Amy Owsley, Maine Coastal Planning Initiative Coordinator Maine State Planning Office 38 State House Station Photography by Terry DeWan, except as Augusta, Maine 04333 noted. -

Aspinquid and Tammany

The Uncertaintist November 30, 2016 http://uncertaintist.wordpress.com I. Aspinquid Early newspaper texts related to Aspinquid, Nova Scotia 1770's Here are four items in the Halifax Gazette (an overall title for a series of newpapers printed by Anthony Henry in the latter 1700's under several different titles). In the transcripts, spelling has been modernized and Americanized. Spelling of Native names, insofar as I could decipher them, have been left character-for-character as I found them. Capitalization, paragraphing and punctuation have been modified for ease of reading. Some words were indecipherable, and what I could make of them was placed in square brackets, [ ... ]. Some Native names are plainly not real names, and are apparently parodies. Lengthy instances of these have also been placed in square brackets. Square brackets are also used for pointers to notes and to modern synonyms for some archaic words. It was only possible to search those issues of the paper which still exist and have made their way online. There may have been other years' feasts which were covered. Following is a table of what was checked. "No" means the issue preceding and the issue following the calculated feast date, as presented online, were found to contain no Aspinquid story. The table also shows whether the Nova Scotia Calender (sic), an almanac with the same printer as the Gazette, told St Aspinquid's day for the year. Year Feast Date Halifax Gazette NS Calender 1770 June 1 Yes ? 1771 May 21 ? ? 1772 May 9 ? Yes 1773 May 28 Yes Yes 1774 May 19 Yes Yes 1775 June 5 No ? 1776 May 24 ? Yes* 1777 May 14 ? Yes 1778 June 2 ? No 1779 May 23 No ? 1780 May 11 No Yes* 1781 May 30 ? ? 1782 May 19 ? ? 1783 May 8 ? ? 1784 May 26 ? No 1785 May 15 ? ? 1786 June 3 ? Yes** 1787 May 24 ? No . -

Preliminary Flood Insurance Study Information Volume 1

VOLUME 1 OF 4 YORK COUNTY, MAINE (ALL JURISDICTIONS) COMMUNITY NAME NUMBER COMMUNITY NAME NUMBER ACTON, TOWN OF 230190 OGUNQUIT, TOWN OF 230632 ALFRED, TOWN OF 230191 OLD ORCHARD BEACH, TOWN OF 230153 ARUNDEL, TOWN Of 230192 PARSONSFIELD, TOWN OF 230154 BERWICK, TOWN OF 230144 SACO, CITY OF 230155 BIDDEFORD, CITY OF 230145 SANFORD, CITY OF 230156 BUXTON, TOWN OF 230146 SHAPLEIGH, TOWN OF 230198 CORNISH, TOWN OF 230147 SOUTH BERWICK, TOWN OF 230157 DAYTON, TOWN OF 230148 WATERBORO, TOWN OF 230199 ELIOT, TOWN OF 230149 WELLS, TOWN OF 230158 HOLLIS, TOWN OF 230150 YORK, TOWN OF 230159 KENNEBUNK, TOWN OF 230151 KENNEBUNKPORT, TOWN OF 230170 KITTERY, TOWN OF 230171 LEBANON, TOWN OF 230193 LIMERICK, TOWN OF 230194 LIMINGTON, TOWN OF 230152 LYMAN, TOWN OF 230195 NEWFIELD, TOWN OF 230196 NORTH BERWICK, TOWN OF 230197 EFFECTIVE: FLOOD INSURANCE STUDY NUMBER 23005CV001A Version Number 2.3.2.1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Volume 1 Page SECTION 1.0 – INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 The National Flood Insurance Program 1 1.2 Purpose of this Flood Insurance Study Report 2 1.3 Jurisdictions Included in the Flood Insurance Study Project 2 1.4 Considerations for using this Flood Insurance Study Report 20 SECTION 2.0 – FLOODPLAIN MANAGEMENT APPLICATIONS 31 2.1 Floodplain Boundaries 31 2.2 Floodways 43 2.3 Base Flood Elevations 44 2.4 Non-Encroachment Zones 44 2.5 Coastal Flood Hazard Areas 45 2.5.1 Water Elevations and the Effects of Waves 45 2.5.2 Floodplain Boundaries and BFEs for Coastal Areas 46 2.5.3 Coastal High Hazard Areas 47 2.5.4 Limit of Moderate Wave Action 48 SECTION